APPENDIX a Historical Overview of the Corridors of Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Germiston South Jurisdiction:- Airport; Albermarle; Asiatic Bazaar; Buhle

Germiston South Jurisdiction:- Airport; Albermarle; Asiatic Bazaar; Buhle Park; Castleview; Cruywagenpark; Dallas Station; Delmenville; Delport; Delville; Denlee; Dewittsrus; Dikatole; Dinwiddie; Driehoek; Egoli Village; Elandshaven; Elsburg; Elspark; Estera; Geldenhuys; Georgetown; Germistoin Industries East; Germiston Industries West; Germiston Lake; Germiston South; Germiston West; Goodhope; Gosforth Park; Graceland; Hazeldene; Hazelpark; Herriotdale; Junction Hill; Jupiter Park Ext 3; Klippoortjie; Klippoortjie Agricultiural Lots; Klippoortjie Park; Knights; Kutalo Hostel; Lake Park; Lambton; Lambton Gardens; Marathon; Mimosa Park; Parkhill Gardens; Pharo Park; Pirowville; Rand Airport; Rondebult; Simmerpan; Summerpark; Tedstoneville; Union Settlements; Wadeville; Webber Germiston North Jurisdiction :- Activia Park; Barvallen; Bedford Gardens; Bedford Park; Bedfordview; Buurendal; Clarens Park; Creston Hill; Dania Park; Dawnview; De Klerkshof; Dowerglen; Dunvegan; Eastliegh; Edenglen; Edenvale; Elandsfontein; Elma Park; Elsieshof; Essexwold; Fisher's Hill; Garden View; Gerdview; Germiston North; Glendower; Greenhills Estate; Harmelia; Henville; Highway Gardens; Homestead; Hurleyvale; Illiondale; Isandovale; Klopperpark; Kruinhof; Malvern East; Maquaksi Plakkers Kamp; Marais-Steyn Park; Marlands; Meadowdale; Morninghill; Oriel; Primrose; Primrose Hill; Primrose Ridge; Rietfontein Hospital; River Ridge; Rustivia; Sebenza; Senderwood; Simmerfield; Solheim; St.Andrews & Exts./Uit; Sunnyridge; Sunnyrock; Symhurst; Symridge; Tunney; Veganview; -

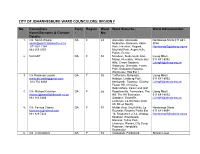

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Renaming of Residences

RENAMING OF RESIDENCES Auckland Park Campus Original Meaning Date of New Name proposed in 2015 Type of Male/Female/Mixed Name Inception Residence Residence Amper Daar Amper Daar is an Afrikaans word 1975 Magnolia – (French). Named after the French Residence Female meaning "Almost there". The name botanist Pierre Magnol. It symbolises divine beauty, has links with the golf course on perseverance, long life and strength. which the University was built. Alomdraai Alomdraai is Afrikaans for full turn. 1977 Akani – (Tsonga). Meaning “To build”. Day House Female Benjemijn Benjemijn is of Dutch origin 1980 Impumelelo – (Nguni). Meaning “'success by working Residence Female meaning “Is jy myne?” or “Are you together”. mine?” Kruinsig Loosely translated means the view 1975 Mošate Heights – (Sepedi). Meaning of Mošate Residence Female from the top. “royal kraal or palace”. Lebone Lebone is a Sotho word for “Dawn 2000 Lebone – (Sotho). Meaning “light”. (Retention of Residence Female of light/Light of achievement”. name) Skoonveld An Afrikaans word which means 1983 Karibu-Jamii – (Kiswahili). Meaning “welcome Residence Female “fairway”. The name recalls the family”. previous golf course and a leisurely past as the University was built on the old Johannesburg Country Club. Afslaan Afslaan translates into “Tee off”. 1968 Afslaan – (Afrikaans). Meaning “tee off” in golf. Residence Male The name recalls the previous golf (Retention of name). course and a leisurely past as the University was built on the old Johannesburg Country Club. Bastion The word “Bastion” refers to the 1980 Maqhawe – (Ndebele/Zulu/Xhosa). Meaning Residence Male strongest cornerstone of a castle. “heroes”. Dromedaris Has a link to “South Africa’s 1975 Cornerstone – (English). -

7.5. Identified Sites of Significance Residential Buildings Within Rosettenville (Semi-Detached, Freestanding)

7.5. Identified sites of significance_Residential buildings within Rosettenville (Semi-detached, freestanding) Introduction Residential buildings are buildings that are generally used for residential purposes or have been zoned for residential usage. It must be noted the majority of residences are over 60 years, it was therefore imperative for detailed visual study to be done where the most significant buildings were mapped out. Their significance could be as a result of them being associated to prominent figures, association with special events, design patterns of a certain period in history, rarity or part of an important architectural school. Most of the sites identified in this category are of importance in their local contexts and are representative of the historical and cultural patterns that could be discerned from the built environment. All the identified sites were given a 3A category explained below. Grading 3A_Sites that have a highly significant association with a historic person, social grouping, historic events, public memories, historical activities, and historical landmarks (should by all means be conserved) 3B_ Buildings of marginally lesser significance (possibility of senstive alteration and addition to the interior) 3C_Buildings and or sites whose significance is in large part significance that contributes to the character of significance of the environs (possibility for alteration and addition to the exterior) Summary Table of identified sites in the residential category: Site/ Description Provisional Heritage Implications -

ANTI-SOCIAL BANDITS Juvenile Delinquency and the Tsotsi Ydut~ Gang Subculture on the Witwatersrand 1935-1960

ANTI-SOCIAL BANDITS Juvenile Delinquency and the Tsotsi YDut~ Gang Subculture on the Witwatersrand 1935-1960 .~. ,__ __ . _. ......""."1 Clive Glaser A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Arts, U~iversity of the Witwatersrand, for the degree of Master of Ar-ts , Johannesburg 1990 I ,.Jt~cla!'e that this d t s se r-t a t iox i': 'n},' .I_JHnt unaided 'Work. I t is be ing subm i tted for the <1.....~ c e./J (" ~1aster of Arts in the UnLve r-sity of the \;',i t.wat.e r-s r-an- :.11: "lnesburg. It has not been submitted before for ,<l"'~' !t::1~. '.:"~ or examination in any other university_ Clive Leonard ~l~ser Thirtieth August, 1990. ACKNOWL~DGEMENTa This thesis would not have been possible without the inspiration and guidance of Phil Bonner .and Peter Delius thrQughout my academi~ career. I am also indebted to all my informants who gaVe up valuable time to speak to me; they asked for nothing in return but an honest account of the past. Don Mattera and Queeneth Ndaba not only mede tim£ to talk bu~ kindly helped me in generating other contacts ~nd setting up interviews. One of my most generous and informat i v e contac t s , StEmley Hotjuwadi, sad Ly died this year. ~ would like to thank Tom Ledge, Gail Gerhar*, David Goodhew, EdWin Ritchken, Fran Buntman and, es~eciallY$ Steve Lebele f~r giving me access to recordIngs or transcriptions of interviews which they conducted jor their own research. In addition, I am grataful to my entire History Masters class f'o ,: providing a supportative and st LmuLet Lng wor-l; environment; the staff of the William Culle;n Library for their friendline_s and efficiency; and my parents fur helping with proofreading. -

Braamfontein Aims to Be National Digital Hub

Views, Comments and Opinion Braamfontein aims to be national digital hub by Hans van de Groenendaal, features editor Prof. Barry Dwolatzky, director of the the Joburg Centre for Sofware Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand believes in the value of an attractive and vibrant digital technolgy hub in Braamfontein to support skills development, job creation, entrepreneurship and the rejuvenation of Johanesburg's inner city. Braamfontein has seen much urban renewal in recent times, and is begining to regain its erstwhile trendiness. Prof. Barry Dwolatzky calls this new digital development the Tshimologong Precinct and is planning to create an exciting new-age software skills and innovation hub. Tshimologong is the seSotho for "place of new beginnings". The precinct is part of an ambitious ICT cluster development programme, Tech-in-Braam, aimed at turning the once dilapidated suburb into the new technical heart of South Africa and beyond. Prof. Dwolatzky is in the process of setting up shop in a series of five unused buildings. After some extensive refurbishments, a one-time night club floor will become a meeting space and will house server rooms; warehouses will be converted into computer labs and retail outlets will reincarnate as development pods. Braamfontein’s many advantages have made the neighbourhood an obvious The Tshimologong precinct will be developed in this part of Braamfontein. location for the precinct – it is convenient to two universities (the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Johannesburg); it is centrally located with good public transport; it is the site of local government departments and many non-governmental organisations; and it is within easy reach of banks and mining houses, as well as a multitude of corporate headquarters. -

The Klip Riviersberg Nature Reserve, the Early Days. Compiled by René

The Klip Riviersberg Nature Reserve, The Early Days. Compiled by René de Villiers. Proclamation of The Reserve The Klip Riviersberg Nature Reserve, or the reserve for short, has always had a special place in the hearts and minds of the people living along its borders and is safe to say that most of the residents in Mondeor feel that way about it. It was certainly the case in the early days of the reserve, and I count myself among them. Since the very early days the Klipriviersberg Nature Reserve Association (KNRA) had been arranging guided walks in the reserve, and with the modest finances at its disposal strove to keep alien vegetation in check, combat fires, arrange guided walks and bring the reserve to the attention of the greater Johannesburg and the rest of the country. One of its earliest projects was to lobby, successfully, for the formal proclamation of the area as a nature reserve. For the record, it was proclaimed on 9th October 1984 in terms of section 14 of the Nature Conservation Ordinance (Ordinance 12 of 1983); Administrator’s Notice 1827. It comprises Erf 49 Alan Manor, Erf 1472 Mondeor, Erf 1353 Kibler Park and Ptn 14 of the Farm Rietvlei 101. All of these erven belong to the (then) Johannesburg City Council Parks and Recreation Department. Portion 17 of the farm Rietvlei 101 which falls within the fenced borders of the reserve, belongs to the University of the Witwatersrand. In all its endeavours the KNRA has done a sterling job and we owe a large debt of gratitude to those early pioneering committees and members in general. -

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa Ivor Chipkin June 2012 / PARI Long Essays / Number 2 Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 3 Preface ........................................................................................................ 5 Introduction: A Common World ................................................................. 7 1. Communal Capitalism ....................................................................... 13 2. Roodepoort City ................................................................................ 28 3.1. The Apartheid City ......................................................................... 33 3.2. Townhouse Complexes ............................................................... 35 3. Middle Class Settlements ................................................................... 41 3.1. A Black Middle Class ..................................................................... 46 3.2. Class, Race, Family ........................................................................ 48 4. Behind the Walls ............................................................................... 52 4.1. Townhouse and Suburb .................................................................. 52 4.2. Milky Way.................................................................................. 55 5. Middle-Classing................................................................................. 63 5.1. Blackness -

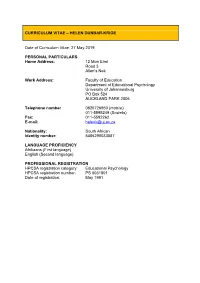

HELEN DUNBAR-KRIGE Date of Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE – HELEN DUNBAR-KRIGE Date of Curriculum Vitae: 27 May 2019 PERSONAL PARTICULARS Home Address: 12 Mon Elmi Road 3 Allen’s Nek Work Address: Faculty of Education Department of Educational Psychology University of Johannesburg PO Box 524 AUCKLAND PARK 2006 Telephone number 0825726950 (mobile) 011-5595249 (Soweto) Fax: 011-5592262 E-mail: [email protected] NationalIty: South African Identity number: 5406290033087 LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY Afrikaans (First language) English (Second language) PROFESSIONAL REGISTRATION HPCSA registration category: Educational Psychology HPCSA registration number: PS 0031801 Date of registration: May 1991 1. ACADEMIC PROFILE 2007 D Ed Educational Psychology University of Johannesburg Title of Thesis: The facilitation of reflection in initial teacher education 1991 M Ed Educational Psychology (cum laude), Rand Afrikaans University 1989 B Ed (Hons) Educational Psychology, Rand Afrikaans University 1978 HED Rand Afrikaans University 1976 BA Social Science, Rand Afrikaans University Majors: History Biblical Studies Psychology 2. CAREER SUMMARY August 2000 to present: Lecturer / Senior lecturer in educational psychology May 1997 to July 2000: Part time lecturer in educational psychology, guidance and counseling August 1996 to August 2000: Educational psychologist in private practice January 1991 to July 1996: School psychologist: Forest Town School for cerebral palsy and learning difficulties Part time private practice January to December 1990 Intern educational psychologist at the Institute for Child and -

Auction Catalogue

APPRECIATING PROPERTY ARCHITECTURE VIRTUAL ONLINE AUCTION EVENT ~ 2 DECEMBER 2020 @ 12:00 ~ Auctioneer: Joff van Reenen DOWNLOAD OUR APP BID ANYWHERE! THIS DYNAMIC APP ALLOWS YOU TO: • Stay Informed • View Properties • Push Notifications The High Street Auction Company APP REGISTRATION & BIDDING PROCESS SIGN UP & APP REGISTRATION PROCESS Ÿ Once you have downloaded the app, open it and click on “VIEW AUCTION” to view our current auction properties. Ÿ In order to bid on a property you will need to SIGN IN. Either click on the drop-down menu top right or click on “REGISTER TO BID”. Ÿ If this is the 1st time using the app please click on “SIGN UP HERE”, otherwise type in your email address and password and sign in. Ÿ Fill in all fields (Please ensure your password is a min. of 8 characters), and tick “Receive bidding notifications via email” & click “CONTINUE”. Ÿ Agree to the Terms of use and click “SIGN UP”. Ÿ Once you have signed up you need to register to bid on a specific auction. Please click on “REGISTER TO BID”. Please note you need to register for each auction to would like to participate in. Ÿ Please complete all the fields and click “CONTINUE”. The High Street Auction Company Ÿ Agree to the Auction Terms & Conditions and click “REGISTER”. Ÿ You will receive a successfully registered message, where you will be approved once all your documents and we have received your proof of payment of your registration fee. ONLINE BIDDING PROCESS Ÿ Once you have been approved by The High Street Auction Co, you will be notified that you can begin to bid. -

City of Johannesburg Pikitup

City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za DEPOT SUBURB/TOWNSHIP PRIORITY AREAS TO BE CLEARED ON FRIDAY, 05 FEB 2016 AVALON DEPOT Eldorado Park Ext 2 and Eldorado Park Proper (Michael Titus 083 260 1776) Eldorado Park Ext 10 and Proper Eldorado Park Ext 1, 3, and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 6 and 4 Eldorado Park Ext 4, Proper and Nancefield Industria Eldorado Park Ext 2, 3 and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 4 and Proper Eldorado Park Proper and M/Park Orange Farm Ext 3 and 1 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Proper CENTRAL CAMP Selinah Pimville Zones 1 - 4 Tshablala 071 8506396 MARLBORO DEPOT Buccleuch ‘Nyane Motaung - 071 850 6395 Sandown City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za MIDRAND DEPOT Cresent wood, Erands gardens, Erands AH and Noordwyk South Jeffrey Mahlangu 082 492 8893 Juskeyview, Waterval estate, South , west and north NORWOOD DEPOT Bruma (Neil Observatory Macherson 071 Kensington 682 1450) Yeoville RANDBURG DEPOT Majoro Letsela Blairgowrie 082 855 9348 ROODEPOORT DEPOT Stella Wilson - Florida 071 856 6822 SELBY DEPOT Fordsburg Sobantwana Mkhuseli CBD 1: (Noord to Commissioner & End to Rissik Streets) 082 855 9321 CBD 2: (Rissik to -

DOORNFONTEIN and ITS AFRICAN WORKING CLASS, 1914 to 1935*• a STUDY of POPULAR CULTURE in JOHANNESBURG Edward Koch a Dissertati

DOORNFONTEIN AND ITS AFRICAN WORKING CLASS, 1914 TO 1935*• A STUDY OF POPULAR CULTURE IN JOHANNESBURG Edward Koch I A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Arts University of the witwatersrand, Johannesburg for the Degree of Master of Arts. Johannesburg 1983. Fc Tina I declare that this dissertation is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of the Wlj Witwaterirand Johanneaourg. It has not been submitted before for any H 1 9 n degree or examination- in any other University. till* dissertation is a study of the culture that was made by tha working people who lived in the slums of Johannesburg in the inter war years. This was a period in which a large proportion of the city's black working classes lived in slums that spread across the western, central and eastern districts of the central city area E B 8 mKBE M B ' -'; of Johannesburg. Only after the mid 1930‘s did the state effectively segregate the city and move most of the black working classes to the municipal locations that they live in today. The culture that was created in the slums of Johannesburg is significant for a number of reasons. This culture shows that the newly formed 1 urban african classes wore not merely the passive agents of capitalism. These people were able to respond, collectively, to the conditions that the development of capitalism thrust them into and to shape and influence the conditions and pro cesses that they were subjected to. The culture that embodied these popular res ponses was so pervasive that it's name, Marabi, is also the name given by many people to the era, between the two world wars, when it thrived.