Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NRAP Calendar Year 18 Expenditure Summary

Date: 1/15/2021 To: Jim Schowalter, Commissioner Minnesota Management and Budget From: Sarah Strommen, Commissioner Department of Natural Resources RE: Natural Resources Asset Preservation Expenditure Summary Report – CY20 Pursuant to Minnesota Statute 84.946, subdivision 4, enclosed is the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources’ Natural Resources Asset Preservation Expenditure Summary Report. This report is a list of projects funded during calendar year 2020 using Natural Resources Asset Preservation appropriations from legislative sessions L14, L17, L18 and L19. If your staff have any questions on this report, please have them contact Peter Hark at 651-259- 5701 or [email protected]. Upon request this report is available in an alternative format. Enclosure CC: Roger Behrens, MMB Shannon Lotthammer, DNR Peter Hark, DNR Mary Robison, DNR Legislative Reference Library Natural Resources Asset Preservation Expenditure Summary Report – Calendar Year 2020 January 1, 2021 Natural Resources Asset Preservation Expenditure Summary Report (M.S. 84.946 Subd. 4) Calendar Year 2020 Expenditures by Project All amounts shown in $ L14 NRAP L17 NRAP L18 NRAP L19 NRAP Total CY20 Project R298611 R298615 R298618 R298625 Expenditures Arrowhead State Trail, Bridge 6,034.00 6,034.00 Beltrami Island State Forest, Road Reconstruction 88,751.00 799.50 89,550.50 Bemidji Area Offices, Roofs 1,080.00 30,401.38 31,481.38 Big Rice Lake WMA, Road 1,080.00 1,080.00 Blue Mounds State Park, Water System 151,130.09 151,130.09 Cambridge Office, Roof 360.00 41,982.00 -

Moves to Amend H.F. No. 5 As Follows: Delete Everything After the Enacting Clause and Insert: "A

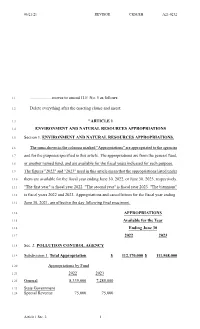

06/21/21 REVISOR CKM/EH A21-0232 1.1 .................... moves to amend H.F. No. 5 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES APPROPRIATIONS 1.5 Section 1. ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES APPROPRIATIONS. 1.6 The sums shown in the columns marked "Appropriations" are appropriated to the agencies 1.7 and for the purposes specified in this article. The appropriations are from the general fund, 1.8 or another named fund, and are available for the fiscal years indicated for each purpose. 1.9 The figures "2022" and "2023" used in this article mean that the appropriations listed under 1.10 them are available for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2022, or June 30, 2023, respectively. 1.11 "The first year" is fiscal year 2022. "The second year" is fiscal year 2023. "The biennium" 1.12 is fiscal years 2022 and 2023. Appropriations and cancellations for the fiscal year ending 1.13 June 30, 2021, are effective the day following final enactment. 1.14 APPROPRIATIONS 1.15 Available for the Year 1.16 Ending June 30 1.17 2022 2023 1.18 Sec. 2. POLLUTION CONTROL AGENCY 1.19 Subdivision 1. Total Appropriation $ 112,170,000 $ 111,568,000 1.20 Appropriations by Fund 1.21 2022 2023 1.22 General 8,339,000 7,285,000 1.23 State Government 1.24 Special Revenue 75,000 75,000 Article 1 Sec. 2. 1 06/21/21 REVISOR CKM/EH A21-0232 2.1 Environmental 89,210,000 89,662,000 2.2 Remediation 14,546,000 14,546,000 2.3 The amounts that may be spent for each 2.4 purpose are specified in the following 2.5 subdivisions. 2.6 The commissioner must present the agency's 2.7 biennial budget for fiscal years 2024 and 2025 2.8 to the legislature in a transparent way by 2.9 agency division, including the proposed 2.10 budget bill and presentations of the budget to 2.11 committees and divisions with jurisdiction 2.12 over the agency's budget. 2.13 Subd. -

A Naturalist's Guide to the Great Plains

Paul A. Johnsgard A Naturalist’s Guide to the Great Plains Sites, Species, and Spectacles This book documents nearly 500 US and Canadian locations where wildlife refuges, na- ture preserves, and similar properties protect natural sites that lie within the North Amer- ican Great Plains, from Canada’s Prairie Provinces to the Texas-Mexico border. Information on site location, size, biological diversity, and the presence of especially rare or interest- ing flora and fauna are mentioned, as well as driving directions, mailing addresses, and phone numbers or internet addresses, as available. US federal sites include 11 national grasslands, 13 national parks, 16 national monuments, and more than 70 national wild- life refuges. State properties include nearly 100 state parks and wildlife management ar- eas. Also included are about 60 national and provincial parks, national wildlife areas, and migratory bird sanctuaries in Canada’s Prairie Provinces. Numerous public-access prop- erties owned by counties, towns, and private organizations, such as the Nature Conser- vancy, National Audubon Society, and other conservation and preservation groups, are also described. Introductory essays describe the geological and recent histories of each of the five mul- tistate and multiprovince regions recognized, along with some of the author’s personal memories of them. The 92,000-word text is supplemented with 7 maps and 31 drawings by the author and more than 700 references. Cover photo by Paul Johnsgard. Back cover drawing courtesy of David Routon. Zea Books ISBN: 978-1-60962-126-1 Lincoln, Nebraska doi: 10.13014/K2CF9N8T A Naturalist’s Guide to the Great Plains Sites, Species, and Spectacles Paul A. -

Hockey Tournaments Keep Our Calendars Full Through March

CRUISIN' THE NORTH COUNTRY BY RV Road trip along MOM’s way, a scenic drive taking you through Manitoba, Ontario and Minnesota. BY CAR & MOTORCYCLE Explore the area on a cross-country fun run organized by the Midwest Motorcycle Club. Start with a Bike & Car Show Friday and on Saturday cruise 100 miles visiting 7 stops. BY BOAT Let our guides take you out on Lake of the Woods for a fishing excursion, all-inclusive with a shore lunch. BY SNOWMOBILE Visit the Polaris Experience Center and spend the rest of the day cruising hundreds of miles of trails. BY RIVER Rent or bring your own fishing boat, canoe or paddleboard and enjoy a quiet meander down the Roseau River, Warroad River, or Rainy River. ROSEAU // WARROAD BY FOOT VISITOR GUIDE 2018 Cruise our downtowns and take in our local shopping, dining, In a world where cruising the internet has never been easier, it’s time to go old culture, and entertainment. school. We invite you to hit the road and head north. Whether you’re traveling by RV, truck, car or motorcycle, you’ll notice the traffic gradually thinning out. BY SKATE Keep going and you’ll soon be the only car on the road. That’s where you’ll find Catch one of hundreds of us. When you arrive, we’ll get you off-road, on the trails, or on the lake. Nestled hockey games in our youth up here next to the Canadian border and Lake of the Woods in northwestern tournaments and high school Minnesota, we’ve got adventures for you for every season. -

State Forest Recreation Guide

Activities abound Camping in State www.mndnr.gov/state_forests in a state forest. Forests... Choose your fun: Your Way Minnesota There are four different ways of • Hiking camping in a state forest. State • Mountain biking 1. Individual Campsites- campsites designated for individuals or single Forest • Horseback riding families. The sites are designed to furnish • Geocaching only the basic needs of the camper. Most consist of a cleared area, fire ring, table, • Canoeing vault toilets, garbage cans, and drinking Recreation water. Campsites are all on a first-come, • Snowmobiling first-served basis. Fees are collected at the sites. Guide • Cross-County Skiing 2. Group Campsites- campsites designated • Biking for larger groups.The sites are designed to furnish only the basic needs of the • OHV riding camper. Most consist of a cleared area, • Camping fire ring, table, vault toilets, garbage cans, and drinking water. Group sites are all on • Fishing a first-come, first-served basis. Fees are collected at the sites. • Hunting 3. Horse Campsites- campsites where • Berry picking horses are allowed. The sites are designed to furnish only the basic needs of the • Birding camper. Most consist of a cleared area, fire ring, table, vault toilets, garbage cans, • Wildlife viewing and drinking water. In addition, these • Wildflower viewing campsites also may have picket lines and compost bins for manure disposal. The State Forest Recreation Guide is published by the Minnesota Department of Campsites are all on a first-come, first- Natural Resources, Division of Forestry, 500 Lafaytte Road, St.Paul, Mn 55155- 4039. Phone 651-259-5600. Written by Kim Lanahan-Lahti; Graphic Design by served basis. -

Protec Ion of Ecologic Lly Sig Ifica T P Atla D in 1\111 Esota

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library \1 LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE LIBRARY as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp G[i!ril~ltli~ilillllli~IIII!!11111111 841393 3 0307 00052 2923 PRELIMINARY REPORT I, PROTEC ION OF I ECOLOGIC LLY SIG IFICA TP ATLA D I IN 1\111 ESOTA GB 625 .M6 MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES P7 :3 4. ,.. % L J I I I I I I I I PRELIMINARY REPORT I PRO.l'FC'l'I<J:il OF EOlIDGlCAILY SIGIIFlCANT P.FATJ:ANIE IN MINNESa.rA I I I Minnesota Department of Natural Resources I June 1984 I I I I I I' I Figures v I Tables vi I FOREL«>RD vii INTROIUCTICN 1 PEATIANDS IN MINNESO'I2\. 3 I Significance of Minnesota's Peatlands 5 I 11 mRIS PEA.TlAND PRCflB:TICN PROGRAM 15 Data Collection--Phase I 15 Nomination of Candidate Areas 16 f Data Collection--Phase II 18 ErDIDGlCAL RESOURCE EVALUATICN 21 I Identification of Peatland Features 21 Evaluation criteria 25 Limitations in the Application of the Evaluation criteria 28 I' Application of the Evaluation criteria 30 Summary of Results 39 MANAGFMENl' OF PEAT.U\ND PRCflB:TICN AREAS 45 I Peatland Management Areas 45 Management Guidelines 48 I IMPACTS OF PEA.TlAND ~ICN CN NATURAL RE:SCJUlC!S MANAGFMENl' 53 Introduction 53 ,Land OWnership 54 'Peat Resources 59 I Timber Resources 62 Wildlife Resources 64 Recreational Resources 67 I Mineral Resources 68 ArMINISTRATIVE AND ImISIATIVE OPTlCES FOR PFJ\TIAND P.Ral'ECl'ICN 73 I Administrative Options 73 Legislative Options 76 I 79 REFERENCES 83 I APPENDIX A- PEATLAND AREAS OF SPECIAL WILDLIFE SIGNIFICANCE I APPENDIX B -- SPECIES STATUS SHEErS I iii I 'I APPENDIX C -- RARE BRYOPHYTES OF PATI'ERNED PEATlANDS IN MINNESarA APPENDIX D -- PEATI.AND CCMPLEX TYPES I APPENDIX E -- DATA SHEETS FOR PEATIAND CANDIDATE AREAS APPENDIX F -- PEATI.AND CANDIDATE AREA MAPS I I I I a I I I I I I' I :1 I I iv I I "I FIGURES PAGE 1. -

Roseau River Watershed District's (RRWD) Overall Plan

OVERALL PLAN JUNE 2004 Roseau RiveR Watershed districT Portions of Beltrami, Kittson, Lake of the Woods, Marshall, and Roseau counties, Minnesota TABLE OF CONTENTS Section I: Introduction ....................................................................................................... 5 Background........................................................................................................................ 5 Watershed Personnel.......................................................................................................... 6 Planning Background......................................................................................................... 7 SECTION II: WATERSHED’S MISSION ................................................................................ 10 History of the District ...................................................................................................... 10 Mission Statement............................................................................................................ 10 Purpose............................................................................................................................. 11 Goals ................................................................................................................................ 11 District’s Policy ............................................................................................................... 12 Rules of the Watershed District...................................................................................... -

Major Parks Argyle Tympanuchus Wildlife 218-281-6063 Management Area State and County Parks 3 Miles E of Harold's Station on Co

Major Parks Argyle Tympanuchus Wildlife 218-281-6063 Management Area State and County Parks 3 miles E of Harold's Station on Co. Rd 45. http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/wmas/index.html Old Mill State Park This 840 acre WMA is open to public hunting, trapping & other 33489 240th Ave. NW compatible recreational uses. It is a remnant tall grass prairie with minor amounts of brush & trees. This area has some of the highest 17 mi. NE of Warren, or 13 miles E of Argyle or 11 miles W of rare species diversity of any WMA. Newfolden on County Road 4. http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/ * State Park fees East Grand Forks Modern camping with showers, flush toilets, 10 electric & water hookups, primitive camping, and 1 group campsite. City Parks/Picnic/Camping Summer Nature Interpretation, enclosed picnic shelter, swimming, canoeing, fishing, volleyball, horseshoe pit, and playground. The Greenway 701-787-3756 Historical sites include a flour grinding mill. Suspension bridges and Sliding Hill in the park. Along the Red River in Grand Forks and East Grand Forks Biking, 7 miles of cross-country skiing and hiking trails, http://www.greenwayggf.com/ Snowshoeing, and 3.5 Miles of groomed trails, warming house with Consists of 2,200 acres lining the Red River & Red Lake River, electricity and fireplace. The park's trails run through prairie, flowing through Greater Grand Forks. This picturesque urban space wooded river valley and pine areas. offers countless recreational, cultural, historical & natural resource opportunities. You can hike, walk, inline skate, bike, cross-country ski, bird, canoe, fish, golf & much more in the heart of our two cities. -

Minnesota House of Representatives

HF5 FIRST ENGROSSMENT REVISOR CKM 211-H0005-1 This Document can be made available Printed in alternative formats upon request State of Minnesota Page No. 8 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SPECIAL SESSION H. F. No. 5 06/14/2021 Authored by Hansen, R., The bill was read for the first time and referred to the Committee on Ways and Means 06/22/2021 Adoption of Report: Placed on the General Register as Amended Read for the Second Time 1.1 A bill for an act 1.2 relating to state government; appropriating money for environment, natural 1.3 resources, and tourism; appropriating money from environment and natural 1.4 resources trust fund; modifying fees and programs; modifying disposition and 1.5 expenditure of certain funds; creating accounts; authorizing sales and conveyances 1.6 of certain state land; adding to and deleting from state parks and recreation areas; 1.7 modifying state land and school trust land provisions; modifying forestry provisions; 1.8 modifying aquaculture provisions; modifying game and fish laws; modifying Water 1.9 Law; modifying natural resource and environment provisions; prohibiting PFAS 1.10 in food packaging; providing for DUI conformity for operating recreational 1.11 vehicles; requiring rulemaking; requiring reports; making technical corrections; 1.12 amending Minnesota Statutes 2020, sections 16B.335, subdivision 2; 17.4982, 1.13 subdivisions 6, 8, 9, 12, by adding subdivisions; 17.4985, subdivisions 2, 3, 5; 1.14 17.4986, subdivisions 2, 4; 17.4991, subdivision 3; 17.4992, subdivision 2; -

ML 2020 ENRTF Work Plan

Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund (ENRTF) M.L. 2020 ENRTF Work Plan (Main Document) Today’s Date: 2/17/2020 Date of Next Status Update Report: April 1, 2021 Date of Work Plan Approval: Project Completion Date: June 2022 Does this submission include an amendment request? No PROJECT TITLE: Peatland Restoration in the Lost River State Forest Project Manager: Torin McCormack Organization: Roseau River Watershed District Mailing Address: 714 6th Street SW City, State, Zip Code: Roseau, MN 56751 Project Manager Direct Telephone Number: 218-452-0179 Email Address: [email protected] Web Address: http://www.roseauriverwd.com/index.html Location: Northwest Region, Lost River State Forest, Roseau County, MN Total Project Budget: $135,000 Amount Spent: $0 Balance: $135,000 Legal Citation: M.L. 2020, Chp. xx, Sec. xx, Subd. xx Appropriation Language: Page 1 of 8 03/02/2020 Subd. 08h - DRAFT PROJECT STATEMENT: The Lost River Forest is a state forest located in Roseau County, Minnesota. Lost River Forest contains approximately 72 square miles of wetlands along the Minnesota-Manitoba border between the cities of Roseau and Warroad Minnesota. Outdoor recreation opportunities in the include camping, fishing, hunting and trails designated for hiking and snowmobiling. Like many large tracts of public land in northern Minnesota, this project area consists of extensive networks of ditches constructed in the early 1900’s to convey surface and subsurface water through the project area promoting agricultural production. Currently agricultural production is very limited. The project area includes Judicial Ditch 61 (JD 61) that removes hydrology from the existing wetlands within the project limits through conveyance resulting in degradation of the peatland wetlands which impacts aquatic and terrestrial habitats. -

Beltrami Island State Forest

MINNESOTA Warroad ONTARIO Lake of the Woods 17 10 Enstrom 11 WMA Lost Lake of the Woods 2 Prosper River WMA 35 Willow 11 11 South Shore 5 11 WMA Prosper State ROSEAU CO Lake WMA Salol 12 12 Cr. Forest of 2 Mandus Cedar Bend Cr. Zippel Bay 11 LAKE OF THE WOODS CO the WMA Swift State Park Pine & Curry Islands SNA 12 Woods 13 17 Zippel 4 West East 34 Four Mile Bay East 8 8 WMA Branch 140 WMA 2 20 124 12 12 12 Br. State 9 5 Br. 12 8 8 2 Warroad 11 Forest 12 4 Hackett 129 Whites Warroad 2 141 Corner Roosevelt 13 River 172 Cr. 2 2 17 Graceton Bog C A N A D A 2 Clear Graceton Bog NW F.R. Bdry. Tomato WMA 5 River Tangnes F.R. Creek WMA 2 WMA Blueberry Hill Williams 132 Road Rd. Campground Roosevelt - Norris F.R. 13 River Ruschs Williams Graceton Bog For. Corner Tangnes Cole F.R. Forest Road Wabanica Krull Cr. Rainy For. 9 126 Area with 2 73 Limitations Wobbles 11 126 126 Bear Clear River 14 WMA Bednar Creek Road Staging Area Ditch 10 F.R. Graceton 6 Road Bednar Carp Pit Sportsmens Area Hooper Cr. WMA Forest Forest River Forest Road Rd. 13 Perry Pit Thompson Schwartz Road 172 Forest Road River 13 R. Bemis Hill F. Cecils For. Winter Landing Carps Rd. 39 Krull For. Rd. Road Pencer Pitt Baudette 20 138 Bemis Hill Root Lake Campground Luxemberg Road Winter 11 F.R. Peatland SNA Tofte For. -

Pursuant to 1982 Session Laws, Ch 511

Pursuant to 1982 Session Laws, ch 511, Section 8, subd 3 This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp I (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) STATE FOREST BOUNDARY PLAN Prepared Pursuant to the Forest Resource Act of 1982 •• 1982 Minnesota Laws, 511~ Section 8 I ·~ By the I State Forest Task Force •• I December 31 1983 11 I I Minnesota of Natural Resources Division of I St. Paul, Minnesota I I I Table of Contents I I Introduction ..................... ·................... • ............ I Study Procedures and Findings: ..•••••••••••••••••.....••••••••••••• 2 I Criteria and Procedure for Establishing State Forest Boundaries ............................................ ·.... 4 I Criteria ..................................................... 4 Procedure ...................................................· .. 5 I Proposed Boundary Changes ••••..••••••••••••••••..•••••.••••••••••• 8 Fond du Lac State Forest 8 I Koochiching State Forest 9 Richard J. Dorer Memorial Hardwood State Forest ••.•••••••••••• 9 I Lost River State Forest .•.•••••••.••••••••••••••.••••••••••••• 9 I References ..•••••....•••••••.•.••••••..•••••.•••.•.•• ~ • • . • . • • • • • • 11 I Appendices A. Excerpts from the Forest Resource Management Act of 1982 (1982 Minn. Laws, Chapter 5 ll) • • . • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • 1 2 I B. State Forest Boundary Task Force Members •••••••••••••••••• 14 C. Excerpts from "A History of Forestry in Minnesota" I (Bachman, 1965) . 1 5 D. Proposed Legislation to Change Selected State I Forest ·Boundaries •••••••••••.••••••••••••••••••• ~ • • • • • • • • • i 9 I I I I I I I INTRODUCTION Recognizing the importance of the state 1 s forest resources, the 1899 II legislature authorized the establishment of public forest reserves to be managed for forestry purposes (1899 Minn. Laws, Chapter 214).