Reflections of Nationalism and the Role of Language Policies in National Identity Formation in Post-Soviet Azerbaijan a Thesis S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPUBLIC of AZERBAIJAN on the Rights of the Manuscript ABSTRACT

REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN On the rights of the manuscript ABSTRACT of the dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philology LITERARY RELATIONS BETWEEN AZERBAIJAN AND GREAT BRITAIN OVER THE PERIOD OF INDEPENDENCE Specialities: 5716.01 – Azerbaijani literature 5718.01 – World Literature (English Literature) Field of science: Philology Applicant: Ilaha Nuraddin Guliyeva Baku - 2021 The work was performed at the World Literature and Comparative Science Department of the Nizami Ganjavi Institute of Literature of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences. Scientific supervisor: Academician, Doctor of science in philology, Professor Isa Akber Habibbeyli Official opponents: Professor, Doctor of Philology, Nigar Valish Isgandarova PhD in philology, Associate Professor Leyli Aliheydar Aliyeva PhD in philology, Associate Professor Razim Ali Mammadov Dissertation council ED – 1.05/1 of Supreme Attestation Commission under the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan operating at the Institute of Literature named after Nizami Ganjavi, Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences Сhairman of the Dissertation Counsil: Academician, Doctor of science in philology, Professor Member _________ Isa Akbar Habibbeyli Scientific Secretary of the Dissertation Council: Doctor of science in philology, Associate Professor _________ Elnara Seydulla Akimova Chairman of the scientific seminar: Doctor of Philology, Associate Professor _________ Aynur Zakir Sabitova 2 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE WORK Revelance and studying degree of the topic. The dissertation Literary relations between Azerbaijan and Great Britain over the period of independence, is devoted to one of the most important and relevant areas of modern comparative literary science. The further development of political, economic, cultural and literary relations with the foreign countries over the period of independence played an important role in the recognition of our country in many countries of the world. -

Chemical Engineering Bachelor Program

CURRICULUM OF DEGREE PROGRAM Course Code Course Name Hours ECTS Prerequisite ENGL 1101 English I 3 6 CHEM 1101 General Chemistry I 3 6 LAB 1101 Introduction To Laboratory Safety & 2 4 Hazardous Materials LAB 1102 General Chemistry Laboratory 2 4 PHYS 1101 Engineering Physics I 3 5 MATH 1101 Calculus For Engineers I 3 5 Course Course Name Hours ECTS Prerequisite Code ENGL 1201 English II 3 5 ENGL 1101 ENG 1201 Introduction to Engineering Design 3 5 COMP 1201 Computers And Chemical Engineering 3 5 CHEM 1201 General Chemistry II 3 5 CHEM 1101 MATH Calculus For Engineers II 3 5 MATH 1101 1201 PHYS 1201 Engineering Physics II 3 5 PHYS 1101 Course Course Name HourS ECTS Prerequisite Code CHEM 2101 Chemical Engineering Material & 3 5 CHEM 1201 Energy Balances CHEM 2102 Organic Chemistry I 3 6 CHEM 1201 EXP 2101 Exposition And Argumentation 3 5 MATH Elementary Differential Equations 3 5 MATH 1201 2101 ENGL 2101 Technical English I 3 5 Free Elective 3 4 Course Course Name Hours ECTS Prerequisite Code CHEM 2201 Professional Practice And Ethics 3 4 CHEM 2202 Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics 3 6 CHEM 2101 I ENGL 2201 Technical English II 3 5 ENGL 2101 COMP 2201 Numerical Computing in Chemical and 3 5 COMP 1201 Biochemical Engineering Technical Elective 3 5 Technical Elective 3 5 Course Course Name Hours ECTS Prerequisite Code CHEM 3101 Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics 3 5 CHEM 2202 II CHEM 3102 Fundamentals of Transport in Chemical 3 5 CHEM 2202 and Biochemical Engineering ENG 3101 Chemical Engineering Reactor Design 3 5 COMP 2201 ECON 3101 -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

Curriculum Vitae Information Form

IFRAT SALIM ALIYEVA Doctor of Philology, Professor Professor of the Department of History of Azerbaijani Literature Work phone: 012-539-09-29 SHORT BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION Born on November 9, 1938 in Baku. In 1946-1956, studied at the Hussein Javid Secondary School. In 1956-1961 studied at the philological faculty of Baku State University. Has been working at BSU since 1962. SCIENTIFIC DEGREE AND SCIENTIFIC NAME In 1962 was a graduate student of the Department of History of Azerbaijani Literature of the Baku State University. In 1971 defended her thesis on the subject “Lyrics of Bakhtiyar Vahabzade” and received the degree of Doctor of Philology. In 1988 defended her thesis on the creative path of Mamed Rahim and received a degree in philology. In 1989 received the title of professor WORK EXPERIENCE In 1962-1968 was a laboratory assistant at the Department of History of Azerbaijani Literature of the BSU In 1968-1971 was a senior laboratory assistant at the Department of History of Azerbaijani Literature of the BSU. In 1971-1973 was a teacher in the department of history of Azerbaijani literature at BSU. In 1973-1979 was an assistant professor in the department of history of Azerbaijani literature at the BSU. In 1919-1980 - Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Philology of the Belarusian State University. In 1980-1988 - Associate Professor, Department of History of Azerbaijani Literature, Baku State University. In 1988-1992 Professor, Department of History of Azerbaijani Literature, Baku State University In 1992-1994 - Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Philology of the Belarusian State University. -

Azərbaycan Respublikasi Mədəniyyət Və Turizm Nazirliyi

AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI MƏDƏNİYYƏT VƏ TURİZM NAZİRLİYİ M.F.AXUNDOV ADINA AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ KİTABXANASI YENİ KİTABLAR Annotasiyalı biblioqrafik göstərici 2010 Buraxılış II B A K I – 2010 AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI MƏDƏNİYYƏT VƏ TURİZM NAZİRLİYİ M.F.AXUNDOV ADINA AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ KİTABXANASI YENİ KİTABLAR 2010-cu ilin ikinci rübündə M.F.Axundov adına Milli Kitabxanaya daxil olan yeni kitabların annotasiyalı biblioqrafik göstəricisi Buraxılış II BAKI - 2010 Tərtibçilər: L.Talıbova N.Rzaquliyeva Baş redaktor: K.Tahirov Redaktor: T.Ağamirova Yeni kitablar: biblioqrafik göstərici /tərtib edənlər L.Talıbova [və b.]; baş red. K.Tahirov; red. T.Ağamirova; M.F.Axundov adına Azərbаycан Milli Kitabxanası.- Bakı, 2010.- Buraxılış II. - 424 s. © M.F.Axundov ad. Milli Kitabxana, 2010 Təbiət elmləri 1. 2-780890 Экологическая экспертиза [Текст]: учебное пособие для студентов вузов, обучающихся по специальности "Экология" /В.К.Донченко, В.М.Питулько, В.В.Растоскуев, С.А.Фролова; под ред. В.М.Питулько; рец. М.П.Федоров, Л.И.Цветкова, А.Г.Емельянов.- М.: Издательский центр "Академия", 2010.- 523 с. В книге дан анализ нормативно-правового обеспечения охраны окружающей среды, природопользования и экологической безопасности в России и за рубежом. Riyaziyyat 2. В1.р Alıyev, R.B. Pedaqoji fakültələrin riyaziyyat kursunda A50 rasional ədədlərin tədrisi yolları [Mətn]: ped. elm. nam. dər. dis. 13.00.02 /Rafiq Alıyev; ADPU.- Bakı, 2007.- 148 s. 3. В1.р Cəfərov, O.C. V-VI siniflərdə şagirdlərin ədədlər C50 nəzəriyyəsi elementlərinə dair biliklərinin genişləndirilməsi və dərinləşdirilməsi [Mətn]: ped. elm. nam. dər. dis.: 13.00.02 /Orxan Cəfərov; Azərb. Resp. Təhsil nazirliyi, Naxşıvan Dövlət un-ti. Naxçıvan, 2008.- 176 s. 4. В127 Davudova, R.İ. -

The Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan – Past and Present 25 History of Science Presidium Building

History of Science 24 www.irs-az.com 4(23), WINTER 2015 Isa HABIBBEYLI, Academician, Vice-President of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences The Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan – Past and Present www.irs-az.com 25 History of Science Presidium building. Photo of the 1930s n the distant past, various organizations, academies and societies were created in various countries aim- Iing to promote the development of science for so- cial progress. Similarly, the Azerbaijani National Acad- emy of Sciences appeared as an objective necessity and played an important role in the development of science, culture and other spheres of social life, in the formation and deepening of social thought and in the strengthening of the national intelligentsia. The acad- emy served as a kind of locomotive for scientific and technological progress and as a forge of public opinion, and later took a leading position in the struggle for the state independence of Azerbaijan, actively contribut- ing to the national awakening of the people and the growth of its identity. The predecessor of today’s Academy was the so- Architectural design of «Ismailia» building. 1914. ciety to explore and study Azerbaijan created in This is where the Presidium of the Academy of 1923. Activities of the society aimed to give concrete Sciences was based afterwards guidance for scientific research and organize expedi- tions and scientific debates, but it was unable to imple- Scientific-Research Institute, which was tasked to ment systematic fundamental research. In 1929, the carry out studies of political and economic nature and CEC of Azerbaijan established an Azerbaijani State deal with educational and methodological challenges. -

Republic of Azerbaijan

REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN On the rights of the manuscript ABSTRACT of the dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Science The 20th century of the Northern Azerbaijan prose and the idea of the divided native land and national-spiritual integrity in the Southern Azerbaijan migration literature Speciality: 5716.01 – Azerbaijani literature Field of science: Philology Applicant: Arzu Huseyn gizi Huseynova Baku - 2021 1 The work was performed at the department of History of Azerbaijan literature of Baku State University Official opponents: Doctor of Sciences in Philology, Professor Maarifa Huseyn gizi Hajiyeva Doctor of Sciences in Philology, Professor Badirkhan Balaja oglu Ahmadov Doctor of Sciences in Philology, Professor Yagub Maharram oglu Babayev Doctor of Sciences in Philology, Associate Professor Ragub Shahmar oglu Karimov Dissertation council ED-1.27 of Supreme Attestation Commission under the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan operating at the Institute of Folklore Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences Chairman of the Dissertation Council: Academician, Doctor of Science in Philology, Professor _______________ Mukhtar Kazim oglu Imanov Scientific secretary of the Dissertation Council: PhD in Philology, Associate Professor _______________ Afag Khurram gizi Ramazanova Chairman of the Scientific Seminar: Doctor of Science in Philology, Professor ________________ Jalal Abil oglu Gasimov 2 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DISSERTATION Topicality and degree of using of the research. In the modern era of globalism Azerbaijani literature -

Hostility in the Pre-War and Post-War Discourse of Armenians

MAY-2021 ANALYSIS AZERBAIJANOPHOBIA IN ARMENIA: HOSTILITY IN THE PRE- WAR AND POST-WAR DISCOURSE OF ARMENIANS Contents Introduction.........................................................................................3 Definitions..………………………………………………….......................................6 Teaching theory of “Tseghakronutyun”……...........................................8 Policy of enmity carried out by Armenians……………............................11 Hostility in the discourse of Armenian politicians, public figures and activists………………………………………………………………………………………......22 Hate speech, hostility and dehumanization of Azerbaijanis by Armenians in social media……………………………………. ........................…46 Conclusion………………..........................................................................59 1 Mirza Ibrahimov 8, Baku, AZ1100, Azerbaijan, Phone: (+994 12) 596-82-39, (+994 12) 596-82-41, E-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION Still a phenomenon inseparable from any ethnic group, ethnocentrism begets cohesion and implies a certain perception of the existing world through the prism of the group that stands at the “center.” According to recent attempts by psychologists to identify the phenomenon, ethnocentrism has been reconceptualized “as a complex multidimensional construct that consists of intergroup expressions of preference, superiority, purity, and exploitativeness, and intragroup expressions of group cohesion and devotion.” In ancient societies, the formation of the image of the “other” and giving a preference to those who were similar -

Xaqan BALAYEV

Xaqan BALAYEV AZƏRBAYCAN DİLİNİN DÖVLƏT DİLİ KİMİ TƏŞƏKKÜL TARİXİNDƏN (XVI-XX əsrlər) Из истории становления Азербайджанского языка как государственного (XVI-XX вв.) Резюме From the history of formation of Azerbaijani as an official language (XVI - XX centuries) Summary BAKI - "Elm və Həyat" – 2002 © Balayev Xaqan Əlirza oğlu. ISBN 9952-8016-0-2 Elmi redaktor: Yaqub MAHMUDOV Tarix elmləri doktoru, professor, əməkdar elm xadimi Balayev X. Azərbaycan dilinin dövlət dili kimi təşəkkül tarixindən (XVI-XX əsrlər). Elmi red. Y.Mahmudov. Bakı, "Elm və Həyat", 2002. 199 səh. ISBN 9952-8016-0-2 1. Azərbaycan dili - Dövlət dili - 2. Azərbaycan dili - tarix (XVI-XX əsrlər) 494. 361'09-dc. 21 Balayev Xaqan Əlirza oğlu. "Azərbaycan dilinin dövlət dili kimi təşəkkül tarixindən (XVI-XX əsrlər)". Kitabda Azərbaycan dilinin dövlət dili kimi təşəkkül tapıb bərqərar olması tarixi, əsasən XX əsr dövrü ilk dəfə tədqiq olunmuşdur. Səfəvilər dövrünə aid sənədlər onlara dair məlumatlarla birlikdə müxtəlif mənbələrdən toplanaraq sistemə salınmışdır. Kitabda, həmçinin, mövzu ilə əlaqədar dövlət sənədləri, arxiv materialları ilk dəfə toplanaraq xronoloji ardıcıllıqla nəşr olunur. B 0501000000 30 "Elm və Həyat" nəşriyyatı Bakı-2002 2 KİTABIN İÇİNDƏKİLƏR Giriş Səfəvilər dövründə Azərbaycan dili (1501-1736) Dövlət dili haqqında ilk sənəd (Azərbaycan Xalq Cümhuriyyəti - 1918-1920) Azərbaycan SSR-də dövlət dili (1920-1991) Azərbaycan Respublikasında dövlət dilinin bərqərar olması Nəticə Из истории становления Азербайджанского языка как государственного (XVI-XX вв.) Резюме From the history of formation of Azerbaijani as an official language (XVI - XX centuries). Summary Sənədlər 1. I Şah İsmayılın Musa Durğut oğluna fərmanı 2. I Şah Təhmasibin II Sultan Səlimə məktubu 3. II Şah Abbasın Şirvan bəylərbəyisi Hacı Mənuçehr xana məktubu 4. -

Between Moscow and Baku: National Literatures at the 1934 Congress of Soviet Writers

Between Moscow and Baku: National Literatures at the 1934 Congress of Soviet Writers by Kathryn Douglas Schild A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Harsha Ram, Chair Professor Irina Paperno Professor Yuri Slezkine Fall 2010 ABSTRACT Between Moscow and Baku: National Literatures at the 1934 Congress of Soviet Writers by Kathryn Douglas Schild Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Harsha Ram, Chair The breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 reminded many that “Soviet” and “Russian” were not synonymous, but this distinction continues to be overlooked when discussing Soviet literature. Like the Soviet Union, Soviet literature was a consciously multinational, multiethnic project. This dissertation approaches Soviet literature in its broadest sense – as a cultural field incorporating texts, institutions, theories, and practices such as writing, editing, reading, canonization, education, performance, and translation. It uses archival materials to analyze how Soviet literary institutions combined Russia’s literary heritage, the doctrine of socialist realism, and nationalities policy to conceptualize the national literatures, a term used to define the literatures of the non-Russian peripheries. It then explores how such conceptions functioned in practice in the early 1930s, in both Moscow and Baku, the capital of Soviet Azerbaijan. Although the debates over national literatures started well before the Revolution, this study focuses on 1932-34 as the period when they crystallized under the leadership of the Union of Soviet Writers. -

Ədəbiyyat Məcmuəsi

AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ ELMLƏR AKADEMİYASI NİZAMİ adına ƏDƏBİYYAT İNSTİTUTU ƏDƏBİYYAT MƏCMUƏSİ NİZAMİ ADINA ƏDƏBİYYAT İNSTİTUTUNUN Ə S Ə R L Ə R İ XXVII cild Bakı – Elm və təhsil – 2016 1 Baş redaktor İsa HƏBİBBƏYLİ AMEA-nın həqiqi üzvü Redaksiya heyəti: Teymur KƏRİMLİ – AMEA-nın həqiqi üzvü Məhərrəm QASIMLI – filologiya üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor Məmməd ƏLİYEV – filologiya üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor Əliyar SƏFƏRLİ – AMEA-nın müxbir üzvü Şirindil ALIŞANLI – filologiya üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor İmamverdi HƏMİDOV – filologiya üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor Nüşabə ARASLI – filologiya üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor Teymur ƏHMƏDOV – filologiya üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor Zaman ƏSGƏRLİ – filologiya üzrə elmlər doktoru Bədirxan ƏHMƏDOV (məsul katib) – filologiya üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor Asif RÜSTƏMLİ – filologiya üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor Tehran ƏLİŞANOĞLU – filologiya üzrə elmlər doktoru, professor Nikpur CABBARLI – filologiya üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru, dosent Eşqanə BABAYEVA – filologiya üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru, dosent Mehparə AXUNDOVA Ədəbiyyat məcmuəsi (Nizami adına Ədəbiyyat İnstitutunun Əsərləri), XXVII c., Bakı, “Elm və təhsil”, 2016. – 330 s. “Ədəbiyyat məcmuəsi” jurnalı Azərbaycan Respublikasının Prezidenti yanında Ali Attestasiya Komissiyasının “Azərbaycan Respublikasında dissertasiyaların əsas nəticələrinin dərc olunması tövsiyə edilən elmi nəşrlərin siyahısı”na daxildir (filologiya elmləri üzrə). Müəllif hüquqları qorunur. Jurnal 1946-cı ildən nəşr olunur. ISSN 2409-5257 © AMEA, Nizami adına Ədəbiyyat İnstitutu, 2016 2 -

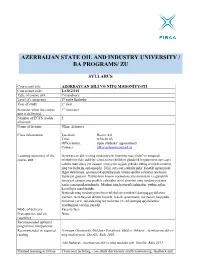

Business Informatics Syllabi

AZERBAIJAN STATE OIL AND INDUSTRY UNIVERSITY / BA PROGRAMS/ ZU SYLLABUS Course unit title AZƏRBAYCAN DİLİ VƏ NİTQ MƏDƏNİYYƏTİ Course unit code LANG1101 Type of course unit Compulsory Level of course unit 1st cycle Bachelor Year of study 1st year Semester when the course 1st Semester unit is delivered Number of ECTS credits 2 allocated Name of lecturer Ülkər Aslanova Class information Location: Room: 4,6 Time: 8:30-10:05 Office hours: upon students’ appointment Contact: [email protected] Learning outcomes of the Azərbaycan dili və nitq mədəniyyəti fənninin əsas hədəf və məqsədi course unit tələbələrin əldə etdikləri elmi-nəzəri bilikləri gündəlik həyatımızın ayrı-ayrı sahələrində ünsiyyət zamanı vəziyyətə uyğun şəkildə tətbiq etməklə mədəni nitq vərdişlərini aşılamaqdır. Dilin ayrı-ayrı sahələrində: fonetik sistemində, lüğət tərkibində, qrammatik quruluşunda xüsusi qəlibə salınmış normalar fəaliyyət göstərir. Tələbələrin həmin normalara yiyələnmələri və gündəlik ünsiyyət zamanı ona praktik cəhətdən əməl etmələri nitq mədəniyyətinin başlıca məqsədlərindəndir. Mədəni nitq hərtərəfli inkişafın, yetkin ağlın, kamilliyin təzahürüdür. Nəticədə nitq mədəniyyəti fənni tələbələrə nəzakətli danışıq qaydalarını öyrədir, Azərbaycan dilinin fonetik, leksik, qrammatik normaları haqqında məlumat verir, onlarda nitq normalarına və etik danışıq qaydalarına yiyələnmək vərdişi yaradır. Mode of delivery Face-to-face Prerequisites and co- None requisites Recommended optional - programme components Recommended or required Nəriman Həsənzadə, Güldanə Pənahova, Ədalət Abbasov. Azərbaycan dili və reading nitq mədəniyyəti. Dərslik. Bakı 2016. Adil Babayev. Azərbaycan dili və nitq mədəniyyəti. Dərslik. Bakı 2011.. Planned learning activities Classroom lecturing, case study discussions and brainstorming, feedback and and teaching methods presentation sessions, discussion sessions Language of instruction Azərbaycan dili Work placement(s) NA Course contents: 1 Mövzu 1.