Report Burma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

BLACK ISLAM SOUTH AFRICA Religious Territoriality, Conversion

BLACK ISLAM SOUTH AFRICA Religious Territoriality, Conversion, and the Transgression of Orderly Indigeneity Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades Dr. phil. im Promotionsfach Geographie am Fachbereich Chemie, Pharmazie, Geographie und Geowissenschaften der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz vorgelegt von Matthias Gebauer geb. in Lichtenfels 2019 i Abstract Social alienation and the struggle to belong in the South African society are not only matters of political discourse but touch the practical sphere of everyday life in the respective places of residence. This thesis therefore approaches the entanglements of religion and space within the processes of re-ordering African indigeneity in post-apartheid South Africa. It asks how conversion to Islam constitutes the longing for a post-colonial and post-racialized African self. This study specifically engages with dynamics surrounding Black and Muslim practices and identity politics in formerly demarcated Black African areas. Here, even after the official end of apartheid, spatial racialization and social inequalities persist. Modes of orderings rooted in colonialism and apartheid still define what orderly belonging and African indigeneity mean. Thus, the inhabitants of those spaces find themselves in situations every day in which their habitat continuously ascribes oppression and racialization. The post-1994 promise for equal citizenship seems to be slowly fading, becoming a broken promise, on whose fulfillment the majority of people who were previously—by official definition and demarcation—only granted the right of being a migratory workforce, sojourners in the White spaces, are still waiting. Against this background, this thesis engages with the attempts to reformulate and recreate African indigeneity on the basis of a counter-hegemonic ideology of being Black and Muslim. -

A Salafi-Jihadi Insurgency in Cabo Delgado?

A Salafi-Jihadi Insurgency in Cabo Delgado? EVOLVING DOCTRINE AND MODUS OPERANDI: VIOLENT EXTREMISM IN CABO DELGADO Thomas Heyen-Dubé & Richard Rands THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Evolving Doctrine and Modus Operandi: Violent Extremism in Cabo Delgado Thomas Heyen-Dubé and Richard Rands Correspondence to: Thomas Heyen. Email [email protected] A violent extremist group poses a significant threat to parts of Cabo Delgado province.1 Since its first major attack in October 2017, it has perpetuated a conflict to the detriment of sections of the population and government, as well as disrupting economic development. Little is known about the group and its various cells, and serious scholarly studies on the topic are scarce. There is a considerable amount of confusion in policymaking and academic circles about the nature of the violent extremists (VE) and their relationship to the wider global Salafi-Jihadi community. By analysing the theological underpinnings of VE and their action in Cabo Delgado (CD), we bring clarity to this debate to enable international actors and policymakers in Mozambique navigate the complexities of the situation. From this analysis we conclude the following: • VE are not Salafi-Jihadis as they do not share their ideological and theological understanding of the world. VE do not subscribe to the notions of tawhid, hakkymiya, jihad, al-wala wa-l-bara, and takfir, all key criteria that are consistently found within the Salafi-Jihadi nebula. 1 For this study, the term violent extremism is used, which defines the actions of the group not their beliefs and ideologies (e.g. -

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

“Fight Is an Inside Path” – a Minor Field Study of How Members of Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi Order Perceive Religious Freedom in Mexico

Södertörn University | School of Historical and Contemporary Studies Bachelor thesis 15 hp | Religious studies | Fall 2014 The program of Journalism target religious studies “Fight is an inside path” – A minor field study of how members of Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi Order perceive religious freedom in Mexico By: Sandra Forsvik Supervisor in Sweden: Simon Sorgenfrei Supervisor in Mexico: Israel Rojas Cámara Abstract The interests for academic studies of contemporary Sufism and Sufism in non-Islamic countries have become more popular, but little has been done in Latin America. The studies of Islam in this continent are limited and studies on Sufism in Mexico seem to be an unexplored area. As a student of journalism target religion I see this as an important topic that can generate new information for the study of Sufism. This thesis is therefore aimed to describe the group of Sufis I have chosen to study, Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi Order in Mexico, linked to Human Rights in form of how members of the Sufi order perceive Religious Freedom in Mexico. A minor field study was carried out in Colonia Roma, Mexico City during October and November 2014. The place was chosen because this is the place where Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi Order exists in Mexico. The investigation is qualitative and based on an ethnographic study of eight weeks and semi structured interviews with three dervishes of the Sufi order, where two of them are men and one is a woman. Based on my purpose I have formulated the following questions: – How do members of Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi -

MYANMAR Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung

I Complex MYANMAR Æ Emergency Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State Imagery analysis: Multiple Dates | Published 18 October 2018 | Version 1.0 CE20130326MMR 92°11'0"E 92°18'0"E 92°25'0"E 92°32'0"E 92°39'0"E 92°46'0"E Thimphu NUMBER OF AFFECTED SETTLEMENTS GROUPED BY LEVEL OF DESTRUCTION ¥¦¬ Level of destruction Buthidaung Maungdaw Rathedaung Total C H I N A Less than 50% destroyed 71 59 4 134 I N D I A More than 50% destroyed 18 62 80 N N Dhaka " Completely destroyed (>90%) 7 156 15 178 " 0 ' 0 ' ¥¦¬ 5 5 2 2 ° ° 1 1 2 Hano¥¦¬i In Tu Lar 2 M YA N M A R ¥¦¬Naypyidaw Vientiane Map location ¥¦¬ T H A I L A N D N N " " 0 ' 0 ' 8 Shee Dar 8 Bangkok 1 1 ° ° 1 1 ¥¦¬ 2 2 Phnom Penh ¥¦¬ Ah Shey Kha Maung Seik Nan Yar Kaing (NaTaLa) Nga/Myin Baw Ku Lar N N " " 0 ' 0 Hpon Thi Laung Boke ' 1 1 Affected settlements in 1 1 ° ° 1 1 2 Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Mu Hti Pa Da Kar Taung 2 Rathedaung Townships of Pa Da Kar Ywar Thit Min Gyi (Ku Lar) Wet Kyein Rakhine State in Myanmar Pe Lun Kha Mway Saung Paing Nyar This map illustrates areas of satellite-detected destroyed or otherwise damaged settlements Goke Pi N N " " 0 ' 0 ' in Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung 4 See inset for close-up view 4 ° ° 1 1 2 Townships in Northern Rakhine State in of destroyed structures 2 Myanmar. -

Rakhine Operational Brief WFP Myanmar

Rakhine Operational Brief WFP Myanmar OVERVIEW Rakhine State is located in the western part of Myanmar, bordering with Chin State in the north, Magway, Bago and Ayeyarwaddy Regions in the east, Bay of Bengal to the west and Chittagong Division of Bangladesh to the northwest. It is one of the most remote and second poorest state in Myanmar, geographically separated from the rest of the country by mountains. The estimated population of Rakhine State is 3.2 million. Chronic poverty and high vulnerability to shocks are widespread throughout the State. Acute malnutrition remains a concern in Rakhine. The food security situation is particularly critical in Buthidaung and Maungdaw townships with 15.1 percent and 19 percent prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) among children 6-59 months respectively. Meanwhile the prevalence of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is 2 percent and 3.9 percent - above WHO critical emergency thresholds. The prevalence of GAM in Sittwe rural and urban IDP camps is 8.6 percent and 8.5 percent whereas the SAM prevalence is 1.3 percent and 0.6 percent. The existing malnutrition has been exacerbated by the 2015 nationwide floods as a Multi-sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA) reported that 22 percent of assessed villages in Rakhine having nutrition problems with feeding children under 2. Moreover, WFP and FAO’s joint Crops and Food Security Assessment Mission in December 2015 predicted the likelihood of severe food shortage particularly in hardest hit areas of Rakhine. WFP is the main humanitarian organization providing uninterrupted food assistance in Rakhine. Its first PARTNERSHIPS operation in Myanmar commenced in 1978 in northern Rakhine, following the return of 200,000 refugees from Government Counterpart Bangladesh. -

Islam in Northern Mozambique: a Historical Overview Liazzat Bonate* University of Cape Town

History Compass 8/7 (2010): 573–593, 10.1111/j.1478-0542.2010.00701.x Islam in Northern Mozambique: A Historical Overview Liazzat Bonate* University of Cape Town Abstract This article is a historical overview of two issues: first, that of the dynamics of Islamic religious transformations from pre-Portuguese era up until the 2000s among Muslims of the contemporary Cabo Delgado, Nampula, and to a certain extent, Niassa provinces. The article argues that histori- cal and geographical proximity of these regions to East African coast, the Comoros and northern Madagascar meant that all these regions shared a common Islamic religious tradition. Accordingly, shifts with regard to religious discourses and practices went in parallel. This situation began chang- ing in the last decade of the colonial era and has continued well into the 2000s, when the so-called Wahhabis, Sunni Muslims educated in the Islamic universities of the Arab world brought religious outlook that differed significantly from the historical local and regional conceptions of Islam. The second question addressed in this article is about relationships between northern Mozambican Muslims and the state. The article argues that after initial confrontations with Muslims in the sixteenth century and up until the last decade of the colonial era, the Portuguese rule pursued no concerted effort in interfering in the internal Muslim religious affairs. Besides, although they occupied and destroyed some of the Swahili settlements, in particular in southern and central Mozambique, other Swahili continued to thrive in northern Mozambique and main- tained certain independence from the Portuguese up until the twentieth century. Islam there remained under the control of the ruling Shirazi clans with close political, economic, kinship and religious ties to the Swahili world. -

MYANMAR Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State

I Complex MYANMAR Æ Emergency Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State Imagery analysis: 31 August - 11 October 2017 | Published 17 November 2017 | Version 1.1 CE20130326MMR N 92°11'0"E 92°18'0"E 92°25'0"E 92°32'0"E 92°39'0"E 92°46'0"E 92°53'0"E N " " 0 ' 0 ' 5 5 Thimphu 2 2 ° ° 1 1 ¥¦¬ 2 Number of affected 2 C H I N A Township I N D I A settlements ¥¦¬Dhaka Buthidaung 34 Hano¥¦¬i Kyaung Toe Maungdaw 225 N Gu Mi Yar N " M YA N M A R " 0 ' 0 ' Naypyidaw 8 8 ¥¦¬ 1 Rathedaung 16 1 ° ° 1 Vientiane 1 2 Map location 2 ¥¦¬ Taing Bin Gar T H A I L A N D Baw Taw Lar Mi Kyaung Chaung Thit Tone Nar Gwa Son Bangkok ¥¦¬ Ta Man Thar Ah Nauk Rakhine Phnom Penh Ta Man Thar Thea Kone Tan Yae Nauk Ngar Thar N N " ¥¦¬ " 0 ' 0 Tat Chaung ' 1 Ye Aung Chaung 1 1 1 ° ° 1 Than Hpa Yar 1 2 Pa Da Kar Taung Mu Hti 2 Kyaw U Let Hpweit Kya Done Ku Lar Kyun Taung Destroyed areas in Buthidaung, Kyet Kyein See inset for close-up view of Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Kyun Pauk Sin Oe San Kar Pin Yin destroyed structures Kyun Pauk Pyu Su Goke Pi Townships of Rakhine State in Hpaw Ti Kaung N Thaung Khu Lar N " " 0 ' 0 ' 4 Gyit Chaung 4 Myanmar ° Sa Bai Kone ° 1 1 2 Lin Bar Gone Nar 2 This map illustrates areas of satellite- Pyaung Pyit detected destroyed or otherwise damaged Yin Ma Kyaung Taung Tha Dut Taung settlements in Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Yin Ma Zay Kone Taung Rathedaung Townships in the Maungdaw and Sittwe Districts of Rakhine State in Myanmar. -

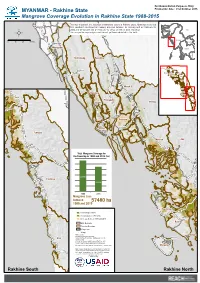

Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015

For Humanitarian Purposes Only MYANMAR - Rakhine State Production date : 21st October 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015 This map illustrates the evolution of mangrove extent in Rakhine State, Myanmar as derived Bhutan from Landsat-5 multispectral imagery acquired between 13 January and 23 February for Nepal Mindat 1988 and 30 January and 24 February for 2015 at 30m of pixel resolution. India China Town Bangladesh Bangladesh This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Paletwa Town Viet Nam Myanmar 0 10 20 30 Kms Laos Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Town Town Maungdaw Thailand Buthidaung Kyauktaw Cambodia Taungpyoletwea Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Town Buthidaung Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Mrauk-U Town Maungdaw Rathedaung Mrauk-U Ponnagyun Town Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Pauktaw Minbya Sittwe Pauktaw Myebon Sittwe Myebon Ann Ann Mrauk-U Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Rathedaung Mrauk-U Munaung Munaung Toungup Town Ann Thandwe Ponnagyun Thandwe Rathedaung Minbya Kyeintali Mindon Ma-Ei Town Town Town Gwa Gwa Ramree Minbya Town Ponnagyun Town Pauktaw Sittwe Pauktaw Town Sittwe Toungup Town Myebon Town Myebon Ann Toungup Town Total Mangrove Coverage for the Township in 1988 and 2015 (ha) Ann Town Thandwe Town 280986 Thandwe 223506 Kyaukpyu 1988 2015 Town Mangrove Loss between 57480 ha 1988 and 2015 Kyaukpyu New Mangrove area Kyeintali Town Remaining area 1988-2015 Ramree Decrease between 1988 and 2015 Town Ramree State Boundary Township Boundary Village-Tract Village Data sources: Toungup Landcover Analysis: UNOSAT Administrative Boundaries, Settlements: OCHA Munaung Gwa Town Roads: OSM Coordinate System: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N Contact: [email protected] File: REACH_MMR_Map_Rakhine_HVA_Mangrove_21OCT2015_A1 Munaung Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Gwa Town on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, associated, donors mentioned on this map. -

139416 Rakhine State

Rakhine State (Myanmar) as of 22 May 2013 Total Estimated IDP Population 139,416 Total Number of Households 22,773 Rakhine Situation Overview Inter-community conflict in Rakhine State, which erupted in early June 2012 and resurfaced in October 2012, has resulted in displacement and loss of lives and livelihoods. As of beginning of April 2013, the number of people displaced in Rakhine State has surpassed 139,000, of whom about 75,000 displaced since June 2012 and the remaining following Kyauktaw October. Many others continue living in tents close to their places of origin while their houses are being rebuilt, or with Maungdaw 6418 host families. The IDP population is currently hosted in 76 camps and camp-like settings. The Shelter/NFI/CCCM Cluster 3569 was activated in December 2012 in Yangon. Only more recently (middle March 2013) did the CCCM Cluster become Mrauk-U operational in Rakhine State. Therefore the sectoral response is still at a very early stage at field level. Rathedaung 4135 4008 Minbya Number of IDP sites by township IDP population by township 5152 as of 22 May 2013 as of 22 May 2013 Sittwe Pauktaw Minbya 8 Minbya 5,152 19976 Meybon Mrauk-U 4 Mrauk-U 4,135 89880 4169 Meybon 2 Meybon 4,169 Pauktaw 6 Pauktaw 19,976 Kyauktaw 11 Kyauktaw 6,418 Rathedaung 4 Rathedaung 4,008 Kyauk Phyu 2 Kyauk Phyu 1,849 Kyauk Phyu Ramree 2 Rakhine Ramree 260 1849 Sittwe 23 Sittwe 89,880 Maungdaw 14 Maungdaw 3,569 Type of accomodation at IDP sites Ramree Number of IDP sites IDP population by type of 260 'Planned / Managed Camp' purpose-built sites by type of accommodation accommodation where services and infrastructure is provided 139,416IDPs including water supply, food distribution, non- food item, education, and health care, usually targeted by humanitarian partners exclusively for the population of the site. -

Languages in the Rohingya Response

Languages in the Rohingya response This overview relates to a Translators without Borders (TWB) study of the role of language in humanitarian service access and community relations in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh and Sittwe, Myanmar. Language use and word choice has implications for culture, identity and politics in the Myanmar context. Six languages play a role in the Rohingya response in Myanmar and Bangladesh. Each brings its own challenges for translation, interpretation, and general communication. These languages are Bangla, Chittagonian, Myanmar, Rakhine, Rohingya, and English. Bangla Bangla’s near-sacred status in Bangladeshi society derives from the language’s tie to the birth of the nation. Bangladesh is perhaps the only country in the world which was founded on the back of a language movement. Bangladeshi gained independence from Pakistan in 1971, among other things claiming their right to use Bangla and not Urdu. Bangladeshis gave their lives for the cause of preserving their linguistic heritage and the people retain a patriotic attachment to the language. The trauma of the Liberation War is still fresh in the collective memory. Pride in Bangla as the language of national unity is unique in South Asia - a region known for its cultural, religious, and linguistic diversity. Despite the elevated status of Bangla, the country is home to over 40 languages and dialects. This diversity is not obvious because Bangladeshis themselves do not see it as particularly important. People across the country have a local language or dialect apart from Bangla that is spoken at home and with neighbors and friends. But Bangla is the language of collective, national identity - it is the language of government, commerce, literature, music and film.