Recovery of 1933∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall of the Global Gold Exchange Standard and the Formation of The

European Research Studies Journal Volume XXIV, Special Issue 1, 2021 pp. 341-347 Fall of the Global Gold Exchange Standard and the Formation of the Contemporary Free Gold Market Submitted 20/01/21, 1st revision 15/02/21, 2nd revision 03/03/21, accepted 20/03/21 Dariusz Eligiusz Staszczak1 Abstract: Purpose: The purpose of this paper is an explanation of the fall of the global gold exchange standard in the beginning of XXth century. Moreover, reasons of the cancelations of the U.S. dollar convertibility into gold according to the fixed parity in 1933 and 1971 are purposes of this paper. The final cancellation of the U.S. dollar gold convertibility was related to the establishment of the free gold market in 1968-1974. A lack of the gold standard and the free gold market are characteristic features of the contemporary world market system. Design / Methodology / Approach: The design is finding the historical reasons of the fall of the global gold exchange standard and of the establishment of the free gold market in 1968- 1974. The research method is a describing political-economic analysis based on statistical data. The approach covers the most important historical time periods connected with the transformation of the global market system including the changing role of the gold. Findings: This paper analyses reasons of the fall of the gold exchange standard from the beginning of the XXth century to the establishment of the free gold market in 1968-1974. Author considers this problem including changes of the global political-economic situation in the analyzed period. -

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS September 1935

SEPTEMBER 1935 OF CURRENT BUSINE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE WASHINGTON VOLUME 15 NUMBER 9 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis UNITED STATES BUREAU OF MINES MINERALS YEARBOOK 1935 The First Complete Official Record Issued in 1935 A LIBRARY OF CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE MINERAL INDUSTRY (In One Volume) Survey of gold and silver mining and markets Detailed State mining reviews Current trends in coal and oil Analysis of the extent of business recovery for vari- ous mineral groups 75 Chapters ' 59 Contributors ' 129 Illustrations - about 1200 Pages THE STANDARD AUTHENTIC REFERENCE BOOK ON THE MINING INDUSTRY CO NT ENTS Part I—Survey of the mineral industries: Secondary metals Part m—Konmetals- Lime Review of the mineral industry Iron ore, pig iron, ferro'alloys, and steel Coal Clay Coke and byproducts Abrasive materials Statistical summary of mineral production Bauxite e,nd aluminum World production of minerals and economic Recent developments in coal preparation and Sulphur and pyrites Mercury utilization Salt, bromine, calcium chloride, and iodine aspects of international mineral policies Mangane.se and manganiferous ores Fuel briquets Phosphate rock Part 11—Metals: Molybdenum Peat Fuller's earth Gold and silver Crude petroleum and petroleum products Talc and ground soapstone Copper Tungsten Uses of petroleum fuels Fluorspar and cryolite Lead Tin Influences of petroleum technology upon com- Feldspar posite interest in oil Zinc ChroHHtt: Asbestos -

Deflation: a Business Perspective

Deflation: a business perspective Prepared by the Corporate Economists Advisory Group Introduction Early in 2003, ICC's Corporate Economists Advisory Group discussed the risk of deflation in some of the world's major economies, and possible consequences for business. The fear was that historically low levels of inflation and faltering economic growth could lead to deflation - a persistent decline in the general level of prices - which in turn could trigger economic depression, with widespread company and bank failures, a collapse in world trade, mass unemployment and years of shrinking economic activity. While the risk of deflation is now remote in most countries - given the increasingly unambiguous signs of global economic recovery - its potential costs are very high and would directly affect companies. This issues paper was developed to help companies better understand the phenomenon of deflation, and to give them practical guidance on possible measures to take if and when the threat of deflation turns into reality on a future occasion. What is deflation? Deflation is defined as a sustained fall in an aggregate measure of prices (such as the consumer price index). By this definition, changes in prices in one economic sector or falling prices over short periods (e.g., one or two quarters) do not qualify as deflation. Dec lining prices can be driven by an increase in supply due to technological innovation and rapid productivity gains. These supply-induced shocks are usually not problematic and can even be accompanied by robust growth, as experienced by China. A fall in prices led by a drop in demand - due to a severe economic cycle, tight economic policies or a demand-side shock - or by persistent excess capacity can be much more harmful, and is more likely to lead to persistent deflation. -

This Is the Heritage Society After All – to 1893, and the Shape of This

1 IRVING HERITAGE SOCIETY PRESENTATION By Maura Gast, Irving CVB October 2010 For tonight’s program, and because this is the Irving Heritage Society, after all, I thought I’d take a departure from my usual routine (which probably everyone in this room has heard too many times) and talk a little bit about the role the CVB plays in an historical context instead. I’m hopeful that as champions of heritage and history in general, that you’ll indulge me on this path tonight, and that you’ll see it all come back home to Irving by the time I’m done. Because there were really three key factors that led to the convention industry as we know it today and to our profession. And they are factors that, coupled with some amazing similarities to what’s going on in our world today, are worth paying attention to. How We as CVBs Came to Be • The Industrial Revolution – And the creation of manufacturing organizations • The Railroad Revolution • The Panic of 1893 One was the industrial revolution and its associated growth of large manufacturing organizations caused by the many technological innovations of that age. The second was the growth of the railroad, and ultimately the Highway system here in the US. And the third was the Panic of 1893. The Concept of “Associations” 2 The idea of “associations” has historically been an American concept – this idea of like‐minded people wanting to gather together in what came to be known as conventions. And when you think about it, there have been meetings and conventions of some kind taking place since recorded time. -

Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany

Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany Maja Adena, Ruben Enikolopov, Maria Petrova, Veronica Santarosa, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya* May 10, 2014 How far can the media protect or undermine democratic institutions in unconsolidated democracies, and how persuasive can they be in ensuring public support for dictator’s policies? We study this question in the context of Germany between 1929 and 1939. Radio slowed down the growth of political support for the Nazis, when Weimar government introduced pro-government political news in 1929, denying access to the radio for the Nazis up till January 1933. This effect was reversed in 5 weeks after the transfer of control over the radio to the Nazis following Hitler’s appointment as chancellor. After full consolidation of power, radio propaganda helped the Nazis to enroll new party members and encouraged denunciations of Jews and other open expressions of anti-Semitism. The effect of Nazi radio propaganda varied depending on the listeners’ predispositions toward the message. Nazi radio was most effective in places where anti-Semitism was historically high and had a negative effect on the support for Nazi messages in places with historically low anti-Semitism. !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! * Maja Adena is from Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. Ruben Enikolopov is from Barcelona Institute for Political Economy and Governance, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona GSE, and the New Economic School, Moscow. Maria Petrova is from Barcelona Institute for Political Economy and Governance, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona GSE, and the New Economic School. Veronica Santarosa is from the Law School of the University of Michigan. Ekaterina Zhuravskaya is from Paris School of Economics (EHESS) and the New Economic School. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

J'une 28, 1933. on This 28Th Day Or June 1933~ the Board· Ot TI

J'une 28, 1933. On this 28th day or June 1933~ the Board· ot TI'U8tees ot the ArkansE State Teachers College met in the President's otti ce at Conway, Arkansas at 11 a.m• with the tbllowing members present and voting: Hirst, Leonard; Humphreys, Compere~ A.ndrews, Fre,uenthe.l ,!Uld: Smith Minutes or the l ast meeting were r ead and approved. Motion by Andrews, seocaded by Smith (l) that Miss Jessie Montgomer be employed as s Upe rvisor tor 1218 jun1 or h igb school in the Training School tor t~ months or July and August at a salaey or $114.90 a month; (2) that Kiss Waldron be assigned in t h9 epi:ropriation budget as auistant int~ DepartmEll.t or Social SoiE11.ce 111.th no change in salary; .(3) that Jerry Dalrymple, Athletic Coach, b.e assigned as adcUtiona.l assistant instead ot an assistant in Social Seienoe, at a salary of ~200.00 a month beginning September l; (4) that the salaries ot Miss Lucy Torson and Miss Edith Langley be made il950 each tor the next year in order to contorm to t he approprta t:l.on bulget; (5) that the resolution passed April 15, 1933 asking the Governor to readjust the amounts appropriated tor salaries in Ite~ 29 and 30 tor 1933-34 be rescinded Motion carrt ed • .llotion by Andrews~ seconded by HumJi>,reys that Guy E. Smith, Disbursing Age~, be instructed to pay tor the grading or oorrespondence papers at the rate ot t l.50 tor each term hours credit; that said payment be paid frcm the Extension Fund upon the eompletion ot each correspondence course; tb:i.t the pa}'JD3nt for tuch work made to meui>ers of tbe regular tacuUy be in addition to salaries tor t.each1ng~ provided that no member or the faculty will be paid more than $450.00 par annum in addi tio:n to the regutar salary. -

Research & Policy Brief No.47

Research & Policy Briefs From the World Bank Malaysia Hub No. 47 May 24, 2021 Demand and Supply Dynamics in East Asia during the COVID-19 Recession Ergys Islamaj, Franz Ulrich Ruch, and Eka Vashakmadze The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated lives and damaged economies, requiring strong and decisive policy responses from governments. Developing Public Disclosure Authorized the optimal short-term and long-term policy response to the pandemic requires understanding the demand and supply factors that drive economic growth. The appropriate policy response will depend on the size and duration of demand and supply shocks. This Research & Policy Brief provides a decomposition of demand and supply dynamics at the macroeconomic level for the large developing economies of East Asia. The findings suggest that both demand and supply shocks were important drivers of output fluctuations during the first year of the pandemic. The demand shocks created an environment of deficient demand—reflected in large negative output gaps even after the unprecedented policy response—which is expected to last through 2021. The extant deficient demand is suggestive of continued need to support the economic recovery. Its size should guide policy makers in calibrating responses to ensure that recovery is entrenched, and that short-term supply disruptions do not lead to long-term declines in potential growth. The Pandemic-Induced Shock Low external demand will continue to affect economies reliant on tourism, while sluggish domestic demand will disproportionally affect The pandemic, national lockdowns, and reverberations from the rest economies with large services sectors. Understanding the demand of the world inflicted a massive shock to the East Asia and Pacific and supply factors that drive economic growth is critical for region in 2020 (World Bank 2020a). -

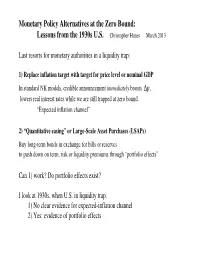

Presentation Slides

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi Party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M. Meissner, Martin McKee, and David Stuckler NBER Working Paper No. 24106 December 2017, Revised in September 2020 JEL No. E6,N1,N14,N44 ABSTRACT We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. Voting data from a thousand districts and a hundred cities for four elections between 1930 and 1933 shows that areas more affected by austerity (spending cuts and tax increases) had relatively higher vote shares for the Nazi party. We also find that the localities with relatively high austerity experienced relatively high suffering (measured by mortality rates) and these areas’ electorates were more likely to vote for the Nazi party. Our findings are robust to a range of specifications including an instrumental variable strategy and a border-pair policy discontinuity design. Gregori Galofré-Vilà Martin McKee Department of Sociology Department of Health Services Research University of Oxford and Policy Manor Road Building London School of Hygiene Oxford OX1 3UQ & Tropical Medicine United Kingdom 15-17 Tavistock Place [email protected] London WC1H 9SH United Kingdom Christopher M. Meissner [email protected] Department of Economics University of California, Davis David Stuckler One Shields Avenue Università Bocconi Davis, CA 95616 Carlo F. Dondena Centre for Research on and NBER Social Dynamics and Public Policy (Dondena) [email protected] Milan, Italy [email protected] Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofr´e-Vil`a Christopher M. Meissner Martin McKee David Stuckler Abstract: We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. -

A Prairie Parable the 1933 Bates Tragedy

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 2009 A Prairie Parable The 1933 Bates Tragedy Bill Walser University of Saskatchewan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Walser, Bill, "A Prairie Parable The 1933 Bates Tragedy" (2009). Great Plains Quarterly. 1235. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1235 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A PRAIRIE PARABLE THE 1933 BATES TRAGEDY BILL WAlSER It was one of the more harrowing episodes of as a relief case. But it was only the child who the Great Depression. Ted and Rose Bates had died when the suicide plan went terribly wrong, failed in business in Glidden, Saskatchewan, in and the parents were charged with murder and 1932 and again on the west coast of Canada the brought to trial in the spring of 1934. following year. When they were subsequently The sorry tale of the Bates family has come turned down for relief assistance twice, first to epitomize the collateral damage wrought in Vancouver and then in Saskatoon, because by the collapse of rural Saskatchewan during they did not meet the local residency require the Great Depression of the 1930s. A popu ments, the couple decided to end their lives in lar Canadian university-level textbook, for a remote rural schoolyard, taking their eight example, uses the tragedy to open the chapter year-old son, Jackie, with them rather than on the Depression.1 Trent University historian face the shame of returning home to Glidden James Struthers, on other hand, employs the incident as an exclamation point. -

Inflation Expectations and Recovery from the Depression in the Spring of 1933: Evidence from the Narrative Record

Inflation Expectations and Recovery from the Depression in the Spring of 1933: Evidence from the Narrative Record Andrew J. Jalil and Gisela Rua* January 2016 Abstract This paper uses the historical narrative record to determine whether inflation expectations shifted during the second quarter of 1933, precisely as the recovery from the Great Depression took hold. First, by examining the historical news record and the forecasts of contemporary business analysts, we show that inflation expectations increased dramatically. Second, using an event- studies approach, we identify the impact on financial markets of the key events that shifted inflation expectations. Third, we gather new evidence—both quantitative and narrative—that indicates that the shift in inflation expectations played a causal role in stimulating the recovery. JEL Classification: E31, E32, E12, N42 Keywords: inflation expectations, Great Depression, narrative evidence, liquidity trap, regime change * Andrew Jalil: Department of Economics, Occidental College, 1600 Campus Road, Los Angeles, CA 90041 (email: [email protected]). Gisela Rua: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Mail Stop 82, 20th St. and Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20551 (email: [email protected]). We are grateful to Pamfila Antipa, Alan Blinder, Michael Bryan, Chia-Ying Chang, Tracy Dennison, Barry Eichengreen, Joshua Hausman, Philip Hoffman, John Leahy, David Lopez-Salido, Christopher Meissner, Edward Nelson, Marty Olney, Jonathan Rose, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Jeremy Rudd, Eugene White, our discussants Carola Binder and Hugh Rockoff, and seminar participants at the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the California Institute of Technology, American University, and Occidental College for thoughtful comments.