The Political Economy of Argentina's Abandonment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin America Economic Outlook

Latin America Economic Outlook August 2014 Contents The world and the region: 1 The outlook for the region remains positive Country outlooks: Argentina 2 Challenging scenario in the short-term Brazil 3 Weak economic activity Chile 4 Low growth Colombia 5 On the right track Ecuador 6 Favorable projections Mexico 7 Recovering economy Peru 8 Unrealized potential for growth Venezuela 9 Structural imbalances unaddressed 10 Macroeconomic variables The world and the region The outlook for the region remains positive 1 2 3 Nearly six years removed from the worst Although global markets generally, and of the subprime crisis, the U.S. economy emerging markets in particular, have thus 4 appears to be slowly returning to normal. far been dependent on the steps that the The economy is growing, employment Fed has taken, recent international fears 5 is up (the unemployment rate is falling), concerning adjustments to its monetary people are spending more, and companies policy are perhaps overblown. A change to 6 are doing their part in terms of investing in the policy would be a natural consequence physical and human capital. of an economy that, after the disruptions 7 of 2008, is resuming development under 8 Even if there is a long road ahead before a more normal conditions. And globally, a return to pre-crisis levels, the ground gained return to relative normalcy by the world’s 9 is plainly evident. And so it is no surprise largest economy can never be bad news. that the Federal Reserve is continuing with On the contrary, both the developed world 10 its plan to cut back on special monetary and emerging economies should benefit stimulus. -

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities A Financial System That T OF EN TH M E A Financial System T T R R A E P A E S That Creates Economic Opportunities D U R E Y H T Nonbank Financials, Fintech, 1789 and Innovation Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation Nonbank Financials, Fintech, TREASURY JULY 2018 2018-04417 (Rev. 1) • Department of the Treasury • Departmental Offices • www.treasury.gov U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation Report to President Donald J. Trump Executive Order 13772 on Core Principles for Regulating the United States Financial System Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary Craig S. Phillips Counselor to the Secretary T OF EN TH M E T T R R A E P A E S D U R E Y H T 1789 Staff Acknowledgments Secretary Mnuchin and Counselor Phillips would like to thank Treasury staff members for their contributions to this report. The staff’s work on the report was led by Jessica Renier and W. Moses Kim, and included contributions from Chloe Cabot, Dan Dorman, Alexan- dra Friedman, Eric Froman, Dan Greenland, Gerry Hughes, Alexander Jackson, Danielle Johnson-Kutch, Ben Lachmann, Natalia Li, Daniel McCarty, John McGrail, Amyn Moolji, Brian Morgenstern, Daren Small-Moyers, Mark Nelson, Peter Nickoloff, Bimal Patel, Brian Peretti, Scott Rembrandt, Ed Roback, Ranya Rotolo, Jared Sawyer, Steven Seitz, Brian Smith, Mark Uyeda, Anne Wallwork, and Christopher Weaver. ii A Financial System That Creates Economic -

Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany

Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany Maja Adena, Ruben Enikolopov, Maria Petrova, Veronica Santarosa, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya* May 10, 2014 How far can the media protect or undermine democratic institutions in unconsolidated democracies, and how persuasive can they be in ensuring public support for dictator’s policies? We study this question in the context of Germany between 1929 and 1939. Radio slowed down the growth of political support for the Nazis, when Weimar government introduced pro-government political news in 1929, denying access to the radio for the Nazis up till January 1933. This effect was reversed in 5 weeks after the transfer of control over the radio to the Nazis following Hitler’s appointment as chancellor. After full consolidation of power, radio propaganda helped the Nazis to enroll new party members and encouraged denunciations of Jews and other open expressions of anti-Semitism. The effect of Nazi radio propaganda varied depending on the listeners’ predispositions toward the message. Nazi radio was most effective in places where anti-Semitism was historically high and had a negative effect on the support for Nazi messages in places with historically low anti-Semitism. !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! * Maja Adena is from Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. Ruben Enikolopov is from Barcelona Institute for Political Economy and Governance, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona GSE, and the New Economic School, Moscow. Maria Petrova is from Barcelona Institute for Political Economy and Governance, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona GSE, and the New Economic School. Veronica Santarosa is from the Law School of the University of Michigan. Ekaterina Zhuravskaya is from Paris School of Economics (EHESS) and the New Economic School. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

The European Payments Union and the Origins of Triffin's Regional Approach Towards International Monetary Integration

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Maes, Ivo; Pasotti, Ilaria Working Paper The European Payments Union and the origins of Triffin's regional approach towards international monetary integration NBB Working Paper, No. 301 Provided in Cooperation with: National Bank of Belgium, Brussels Suggested Citation: Maes, Ivo; Pasotti, Ilaria (2016) : The European Payments Union and the origins of Triffin's regional approach towards international monetary integration, NBB Working Paper, No. 301, National Bank of Belgium, Brussels This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/173757 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Wall St. and the Law: Customer Fund Protections After the Collapse of MF Global and Peregrine -- What Regulatory Changes Are Taking Place

E TUT WALL ST. AND THE LAW: I CUSTOMER FUND PROTECTIONS ST AFTER THE COLLApsE OF MF N GLOBAL AND PEREGRINE – WHAT REGULATORY CHANGES ARE TAKING PLACE Prepared in connection with a Continuing Legal Education course presented at New York County Lawyers’ Association, 14 Vesey Street, New York, NY presented on Tuesday, June 18, 2013. P ROGR A M C O - S P O N SOR : New York Law (NYLS) School Financial Services Law Institute P ROGR A M M OD E R A TOR : Prof. Ronald H. Filler, NYLS Professor of Law and, Director, Financial Services Law Institute, NYLS P ROGR A M F ac U L T Y : Steven Lofchie, Cadwalader Wickersham & Taft; Robert L. Sichel, Pacific Global Advisors; Gary DeWaal , Gary DeWaal & Associates (former Group General Counsel of Newedge) NYCLA-CLE I 2 TRANSITIONAL & NON-TRANSITIONAL MCLE CREDITS: This course has been approved in accordance with the requirements of the New York State Continuing Legal Education Board for a maximum of 2 Transitional & Non-Transitional credit hours: .5 Ethics; 1.5 PP This program has been approved by the Board of Continuing Legal Education of the Supreme Court of New Jersey for 2 hours of total CLE credit. Of these, 0 qualify as hours of credit for Ethics/Professionalism, and 0 qualify as hours of credit toward certification in civil trial law, criminal trial law, workers compensation law and/or matrimonial law. Information Regarding CLE Credits and Certification Wall Street and the Law June 18, 2013; 6:00 PM to 8:00 PM The New York State CLE Board Regulations require all accredited CLE providers to provide documentation that CLE course attendees are, in fact, present during the course. -

Presentation Slides

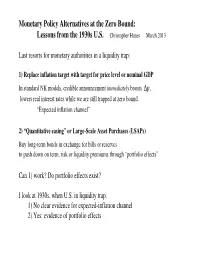

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

Banking Policy Issues in the 115Th Congress

Banking Policy Issues in the 115th Congress David W. Perkins Analyst in Macroeconomic Policy March 7, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44855 Banking Policy Issues in the 115th Congress Summary The financial crisis and the ensuing legislative and regulatory responses greatly affected the banking industry. Many new regulations—mandated or authorized by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203) or promulgated under the authority of bank regulators—have been implemented in recent years. In addition, economic and technological trends continue to affect banks. As a result, Congress is faced with many issues related to the bank industry, including issues concerning prudential regulation, consumer protection, “too big to fail” (TBTF) banks, community banks, regulatory agency design and independence, and market and economic trends. For example, the Financial CHOICE Act (H.R. 10) and the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (S. 2155) propose wide ranging changes to the financial regulatory system, and include provisions related to many of these banking issues. Prudential Regulation. This type of regulation is designed to ensure banks are safely profitable and unlikely to fail. Regulatory ratio requirements agreed to in the international agreement known as the Basel III Accords and the Volcker Rule are examples. Ratio requirements require banks to hold a certain amount of capital on their balance sheets to better enable them to avoid failure. The Volcker Rule prohibits certain trading activities and affiliations at banks. Proponents argue the rules appropriately balance the need for safety and soundness with regulatory burden. -

The Clearing House Interbank Payments System: a Description of Its Operation and Risk Management

No. 8910 THE CLEARING HOUSE INTERBANK PAYMENTS SYSTEM: A DESCRIPTION OF ITS OPERATION AND RISK MANAGEMENT by Robert T. Clair* Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas June 1989 Research Paper Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas This publication was digitized and made available by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas' Historical Library ([email protected]) t No. 8910 THE CLEARIIIGHOUSE IIITERBAIIK PAYI,IEI{TS SYSTEII: A DTSCRIPTIOXOF ITS OPERATIOI{AND RISKI.IA}IAGEI{II{T by Robert T. Clair* Federal ReserveBank of Dallas Jurn 198!l * Theviews expressed .in this article are solely thoseof the authorand shouldnot be attributed to the FederalReserve Bank of Dallas. or the FederalReserve System. The Clearing HouseInterbank Payments System: Descriptionof Its 0perationsand Risk Manaqement 1. General0vervjew of the System The Clearing HouseInterbank Payment Systenr (CHIPS) is a high-speed message-s\4itchingnetwork owned and operatedby the Newyork Clearing House Assoc'iation(NYCHA) to clear jnternationaldollar payments.Based 'in Newyork Cit.y, CHIPSwas developed in the late 1960sas an e'lectronic replacementfor a paper-basedpayment system, the PaperExchange Payment System (PEPS), PEPSprovided an effective clearjng arrangementbut the paper-based strtrcturewas unable to handlethe rapidly growingvolume of paynentsthat neededto be cleared. Thegrowth in paymentvolume was partial'iy the resu'lt of the growthof the Eurodollarmarket.l Thechange in foreign exchangerate r For a discussionof the causesfor the surge in the Eurodollar market,see Sarkjs J. Khoury,Dynamics of I nternati ona'lBank ing, Praeger1980,p.24-6. regine from fjxed to floating rates jn lg73 also ljkely jncreasedthe volumeof internationa.l paymentsthat neededto be cleared. In responseto the growingvolurne of internationdl paymentsthe NYCHA developedthe ClearingHouse Interbank Payments System (CHIPS). -

Maine Alumnus, Volume 11, Number 3, December 1929

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine University of Maine Alumni Magazines University of Maine Publications 12-1929 Maine Alumnus, Volume 11, Number 3, December 1929 General Alumni Association, University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation General Alumni Association, University of Maine, "Maine Alumnus, Volume 11, Number 3, December 1929" (1929). University of Maine Alumni Magazines. 99. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines/99 This publication is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maine Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PURCHASING AGENT UN IV. OF ME. ORONO, ME. Coburn H all Volume 1 1 December, 1929 Number 3 University L oyalty to A lu m n i “The game of last Saturday with Colby will go down in my memory as one of the outstanding contests played by a Maine team. I have never seen a better example of ‘Maine spirit’, clean playing, and determination to win. That we lost is no disgrace. Everyone who saw the game should be proud of the team and of the fact that even against heavy odds every moment was full of fight and aggressiveness.” This message was sent to the student body by President Boardman en route to Chicago and the Pacific Coast. Presi dent Boardman was authorized by unanimous vote of the Board of Trustees to make this 6000 mile coast-to-coast trip for the purpose of carrying the spirit and news of the Univer sity to the Alumni Associations of the middle west and Pacific coast and to bring back to the campus the spirit of the far west ern alumni associations. -

The Foreign Service Journal, December 1929

THfe AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL CARACAS, VENEZUELA Entrance to Washington Building, in which the American Consulate is located Vol. VI DECEMBER, 1929 No. 12 BANKING AND INVESTMENT SERVICE THROUGHOUT THE WORLD The National City Bank of New York and Affiliated Institutions THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK CAPITAL, SURPLUS AND UNDIVIDED PROFITS $238,516,930.08 (AS OF OCTOBER 4, 1929) HEAD OFFICE THIRTY-SIX BRANCHES IN 56 WALL STREET. NEW YORK GREATER NEW YORK Foreign Branches in ARGENTINA . BELGIUM . BRAZIL . CHILE . CHINA . COLOMBIA . CUBA DOMINICAN REPUBLIC . ENGLAND . INDIA . ITALY . JAPAN . MEXICO . PERU . PORTO RICO REPUBLIC OF PANAMA . STRAITS SETTLEMENTS . URUGUAY . VENEZUELA. THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK (FRANCE) S. A. Paris 41 BOULEVARD HAUSSMANN 44 AVENUE DES CHAMPS ELYSEES Nice: 6 JARDIN du Roi ALBERT ler INTERNATIONAL BANKING CORPORATION (OWNED BY THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) Head Office: 55 WALL STREET, NEW YORK Foreign and Domestic Branches in UNITED STATES . PHILIPPINE ISLANDS . SPAIN . ENGLAND and Representatives in The National City Bank Chinese Branches. BANQUE NATIONALE DE LA REPUBLIQUE D’HAITI . (AFFILIATED WITH THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) Head Office: PORT AU-PRINCE, HAITI CITY BANK FARMERS TRUST COMPANY {formerly The farmers* Loan and Trust Company—now affiliated with The National City Bank of New York) Head Office: 22 WILLIAM STREET, NEW YORK Temporary Headquarters: 45 EXCHANGE PLACE THE NATIONAL CITY COMPANY (AFFILIATED WITH THE NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK) HEAD OFFICE OFFICES IN SO LEADING 55 WALL STREET, NEW YORK AMERICAN CITIES Foreign Offices: LONDON . AMSTERDAM . COPENHAGEN . GENEVA . TOKIO . SHANGHAI Canadian Offices: MONTREAL . -

The Rise and Fall of Argentina

Spruk Lat Am Econ Rev (2019) 28:16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40503-019-0076-2 Latin American Economic Review RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The rise and fall of Argentina Rok Spruk* *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract School of Economics I examine the contribution of institutional breakdowns to long-run development, and Business, University of Ljubljana, Kardeljeva drawing on Argentina’s unique departure from a rich country on the eve of World ploscad 27, 1000 Ljubljana, War I to an underdeveloped one today. The empirical strategy is based on building Slovenia a counterfactual scenario to examine the path of Argentina’s long-run development in the absence of breakdowns, assuming it would follow the institutional trends in countries at parallel stages of development. Drawing on Argentina’s large historical bibliography, I have identifed the institutional breakdowns and coded for the period 1850–2012. The synthetic control and diference-in-diferences estimates here suggest that, in the absence of institutional breakdowns, Argentina would largely have avoided the decline and joined the ranks of rich countries with an income level similar to that of New Zealand. Keywords: Long-run development, New institutional economics, Political economy, Argentina, Applied econometrics JEL Classifcation: C23, K16, N16, N46, O43, O47 1 Introduction On the eve of World War I, the future of Argentina looked bright. Since its promulga- tion of the 1853 Constitution, Argentina had experienced strong economic growth and institutional modernization, which had propelled it into the ranks of the 10 wealthi- est countries in the world by 1913. In the aftermath of the war, Argentina’s income per capita fell from a level approximating that of Switzerland to its current middle-income country status.