Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discrimination and Law in Nazi Germany

Cohen Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies Name:_______________________________ at Keene State College __________________________________________________________________________________________________ “To Remember…and to Teach.” www.keene.edu/cchgs Student Outline: Destroying Democracy From Within (1933-1938) 1. In the November 1932 elections the Nazis received _______ (%) of the vote. 2. Hitler was named Chancellor of a right-wing coalition government on _________________ _____, __________. 3. Hitler’s greatest fear is that he could be dismissed by President ____________________________. 4. Hitler’s greatest unifier of the many conservatives was fear of the _____________. 5. The Reichstag Fire Decree of February 1933 allowed Hitler to use article _______ to suspend the Reichstag and suspend ________________ ____________ for all Germans. 6. In March 5, 1933 election, the Nazi Party had _________ % of the vote. 7. Concentration camps (KL) emerged from below as camps for “__________________ ________________” prisoners. 8. On March 24, 1933, the _______________ Act gave Hitler power to rule as dictator during the declared “state of emergency.” It was the __________________ Center Party that swayed the vote in Hitler’s favor. 9. Franz Schlegelberger became the State Secretary in the German Ministry of ___________________. He believed that the courts role was to maintain ________________ __________________. He based his rulings on the principle of the ____________________ ___________________ order. He endorsed the Enabling Act because the government, in his view, could act with _______________, ________________, and _____________________. 10. One week after the failed April 1, 1933 Boycott, the Nazis passed the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional _________________ ______________________. The April 11 supplement attempted to legally define “non-Aryan” as someone with a non-Aryan ____________________ or ________________________. -

Výmarská Ústava 1919

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Právnická fakulta Katedra teorie práva a právních dějin Milan Cigánek Výmarská ústava 1919 Diplomová práce Vedoucí diplomové práce: Mgr. Jana Janišová, Ph.D. OLOMOUC 2010 1 Já, níţe podepsaný Milan Cigánek, autor diplomové práce na téma „Výmarská ústava 1919“, která je literárním dílem ve smyslu zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským, dávám tímto jako subjekt údajů svůj souhlas ve smyslu § 4 písm. e) zákona č. 101/2000 Sb., správci: Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, Kříţkovského 8, Olomouc, 771 47, Česká Republika ke zpracování osobních údajů v rozsahu: jméno a příjmení v informačním systému, a to včetně zařazení do katalogů, a dále ke zpřístupnění jména a příjmení v informačních systémech Univerzity Palackého, a to včetně zpřístupnění pomocí metod dálkového přístupu. Údaje mohou být takto zpřístupněny uţivatelům sluţeb Univerzity Palackého. Realizaci zpřístupnění zajišťuje ke dni tohoto prohlášení patřičná vnitřní sloţka Univerzity Palackého, Knihovna UP. Souhlas se poskytuje na dobu ochrany autorského díla dle zákona č. 121/2000 Sb. *** Prohlašuji tímto, ţe moje osobní údaje výše uvedené jsou pravdivé. Prohlašuji, ţe jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracoval samostatně a uvedl v ní veškerou literaturu a ostatní informační zdroje, které jsem pouţil. V Němčanech dne 28. 2. 2010 Milan Cigánek 2 Poděkování Rád bych touto cestou vyjádřil své upřímné poděkování za cenné připomínky, ochotu, pomoc a spolupráci vedoucí mé diplomové práce, paní Mgr. Janě Janišové, Ph.D. 3 Obsah 1. Úvod 7 1.1. Metodologie 8 1.2. Diskuse pramenů a literatury 9 2. Kontury vývoje Německa po prohrané válce 13 2.1. Předrevoluční tání 13 2.2. -

Presentation Slides

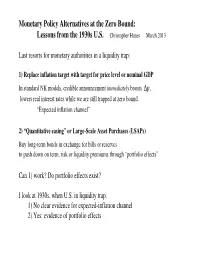

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi Party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M. Meissner, Martin McKee, and David Stuckler NBER Working Paper No. 24106 December 2017, Revised in September 2020 JEL No. E6,N1,N14,N44 ABSTRACT We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. Voting data from a thousand districts and a hundred cities for four elections between 1930 and 1933 shows that areas more affected by austerity (spending cuts and tax increases) had relatively higher vote shares for the Nazi party. We also find that the localities with relatively high austerity experienced relatively high suffering (measured by mortality rates) and these areas’ electorates were more likely to vote for the Nazi party. Our findings are robust to a range of specifications including an instrumental variable strategy and a border-pair policy discontinuity design. Gregori Galofré-Vilà Martin McKee Department of Sociology Department of Health Services Research University of Oxford and Policy Manor Road Building London School of Hygiene Oxford OX1 3UQ & Tropical Medicine United Kingdom 15-17 Tavistock Place [email protected] London WC1H 9SH United Kingdom Christopher M. Meissner [email protected] Department of Economics University of California, Davis David Stuckler One Shields Avenue Università Bocconi Davis, CA 95616 Carlo F. Dondena Centre for Research on and NBER Social Dynamics and Public Policy (Dondena) [email protected] Milan, Italy [email protected] Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofr´e-Vil`a Christopher M. Meissner Martin McKee David Stuckler Abstract: We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

The Political Economy of Argentina's Abandonment

Going through the labyrinth: the political economy of Argentina’s abandonment of the gold standard (1929-1933) Pablo Gerchunoff and José Luis Machinea ABSTRACT This article is the short but crucial history of four years of transition in a monetary and exchange-rate regime that culminated in 1933 with the final abandonment of the gold standard in Argentina. That process involved decisions made at critical junctures at which the government authorities had little time to deliberate and against which they had no analytical arsenal, no technical certainties and few political convictions. The objective of this study is to analyse those “decisions” at seven milestone moments, from the external shock of 1929 to the submission to Congress of a bill for the creation of the central bank and a currency control regime characterized by multiple exchange rates. The new regime that this reordering of the Argentine economy implied would remain in place, in one form or another, for at least a quarter of a century. KEYWORDS Monetary policy, gold standard, economic history, Argentina JEL CLASSIFICATION E42, F4, N1 AUTHORS Pablo Gerchunoff is a professor at the Department of History, Torcuato Di Tella University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [email protected] José Luis Machinea is a professor at the Department of Economics, Torcuato Di Tella University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [email protected] 104 CEPAL REVIEW 117 • DECEMBER 2015 I Introduction This is not a comprehensive history of the 1930s —of and, if they are, they might well be convinced that the economic policy regarding State functions and the entrance is the exit: in other words, that the way out is production apparatus— or of the resulting structural to return to the gold standard. -

Inflation Expectations and Recovery from the Depression in the Spring of 1933: Evidence from the Narrative Record

Inflation Expectations and Recovery from the Depression in the Spring of 1933: Evidence from the Narrative Record Andrew J. Jalil and Gisela Rua* January 2016 Abstract This paper uses the historical narrative record to determine whether inflation expectations shifted during the second quarter of 1933, precisely as the recovery from the Great Depression took hold. First, by examining the historical news record and the forecasts of contemporary business analysts, we show that inflation expectations increased dramatically. Second, using an event- studies approach, we identify the impact on financial markets of the key events that shifted inflation expectations. Third, we gather new evidence—both quantitative and narrative—that indicates that the shift in inflation expectations played a causal role in stimulating the recovery. JEL Classification: E31, E32, E12, N42 Keywords: inflation expectations, Great Depression, narrative evidence, liquidity trap, regime change * Andrew Jalil: Department of Economics, Occidental College, 1600 Campus Road, Los Angeles, CA 90041 (email: [email protected]). Gisela Rua: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Mail Stop 82, 20th St. and Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20551 (email: [email protected]). We are grateful to Pamfila Antipa, Alan Blinder, Michael Bryan, Chia-Ying Chang, Tracy Dennison, Barry Eichengreen, Joshua Hausman, Philip Hoffman, John Leahy, David Lopez-Salido, Christopher Meissner, Edward Nelson, Marty Olney, Jonathan Rose, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Jeremy Rudd, Eugene White, our discussants Carola Binder and Hugh Rockoff, and seminar participants at the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the California Institute of Technology, American University, and Occidental College for thoughtful comments. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

Radio and the Rise of Nazi in Pre-War Germany*

Radio and the rise of Nazi in pre-war Germany* Maja Adena, Ruben Enikolopov, Maria Petrova, Veronica Santarosa, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya1 March 22 2012 How far can media undermine democratic institutions and how persuasive can it be in assuring public support for dictator policies? We study this question in the context of Germany between 1929 and 1939. Using quasi-random geographical variation in radio availability, we show that radio had a significant negative effect on the Nazi vote share between 1930 and 1933, when political news had an anti-Nazi slant. This negative effect was fully undone in just one month after Nazi got control over the radio in 1933 and initiated heavy radio propaganda. Radio also helped the Nazi to enroll new party members and encouraged denunciations of Jews and other open expressions of anti-Semitism after Nazi fully consolidated power. Nazi radio propaganda was most effective when combined with other propaganda tools, such as Hitler’s speeches, and when the message was more aligned with listeners’ prior as measured by historical anti-Semitism. !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! * We are grateful to Jürgen W. Falter, Nico Voigtländer, Hans-Joachim Voth, and Bundesarchive for sharing their data. We thank Ben Olken for providing the software for ITM calculation. We also thank Anton Babkin, Natalia Chernova, Ivan Korolev, and Gleb Romanyuk for excellent research assistance. 1 Maja Adena is from Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. Ruben Enikolopov is from the Institute for Advanced Study and the New Economic School, Moscow. Maria Petrova is from Princeton University and the New Economic School. Veronica Santarosa is from the Law School of the University of Michigan. -

1923 Inhaltsverzeichnis

1923 Inhaltsverzeichnis 14.08.1923: Regierungserklärung .............................................................................. 2 22.08.1923: Rede vor dem Schutzkartell für die notleidende Kulturschicht Deutschlands ........................................................................................ 14 24.08.1923: Rede vor dem Deutschen Industrie- und Handelstag ........................... 18 02.09.1923: Rede anläßlich eines Besuchs in Stuttgart ........................................... 36 06.09.1923: Rede vor dem Verein der ausländischen Presse in Berlin .................... 45 12.09.1923: Rede beim Empfang des Reichspressechefs in Berlin ......................... 51 06.10.1923: Regierungserklärung ............................................................................ 61 08.10.1923: Reichstagsrede ..................................................................................... 97 11.10.1923: Erklärung im Reichstag ........................................................................119 24.10.1923: Rede in einer Sitzung der Ministerpräsidenten und Gesandten der Länder in der Reichkanzlei ..................................................................121 25.10.1023: a) Rede bei einer Besprechung mit den Vertretern der besetzten Gebiete im Kreishaus in Hagen ..........................................................................................147 b) Rede in Hagen .................................................................................................178 05.11.1923: Redebeitrag in der Reichstagsfraktion -

Lesson 8: Handout 1 Timeline: Hitler’S Rise to Power

Lesson 8: Handout 1 Timeline: Hitler’s rise to power 1. 1919 — Weimar Constitution is adopted. The constitution creates separate executive, judicial, and legislative branches of government so that one group or person cannot hold all of the power. It also includes articles protecting civil liberties (freedoms) such as freedom of speech, freedom of assembly (freedom to meet in public), and freedom of religion. The constitution also protects privacy so that individuals cannot be searched without the court’s permission. 2. 1919 — The constitution includes Article 48. This article suspends the constitution in times of emergency, allowing the president to make rules without the consent of the parliament and to suspend (put on hold) civil rights, like freedom of speech, in order to protect public safety. Many people thought this article was a good idea because there were so many political parties in Germany that sometimes it was difficult for them to agree enough to pass any laws. At times of crisis, like the inflation Germany suffered in 1923 or the depression in 1929, it was important for government to respond quickly and not be held from action by politicians who can not agree. Thus, many Germans thought it would be wise to have a clause in the constitution that would allow the president to take over and make quick decisions in times of emergency. 3. July 1932 — The Nazi Party wins 37% of the votes. For the first time, the Nazis are the largest and most powerful political party in Germany. Still, over half of the German citi - zens do not vote for the Nazis and they still do not have enough seats in the Reichstag (parliament) to be able to pass laws without getting additional votes from representa - tives from other political parties. -

Towards an Open Learning World: 50 Years. UNESCO Institute for Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 473 660 CE 084 399 AUTHOR Elfert, Maren, Ed. TITLE Towards an Open Learning World: 50 Years. UNESCO Institute for Education. INSTITUTION United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Hamburg (Germany). Inst. for Education. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 107p.; Photographs may not reproduce well. Translation to English by Peter Sutton. AVAILABLE FROM UNESCO Publishing, Commercial Services, 7, place de Fontenoy, F 75352 Paris (free; available in English, French and German). E-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.unesco.org/education/uie/index.shtml. For full text: http://www.unesco.org/education/uie/pdf/50yearseng.pdf. For full text (French): http://www.unesco.org/education/uie/pdf/50yearsfre.pdf. For full text (German): http://www.unesco.org/ education/uie/pdf/50yearsger.pdf. PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Access to Education; Adult Basic Education; Adult Education; *Adult Learning; Chronicles; Culturally Relevant Education; Delivery Systems; Developing Nations; Educational Development; Educational Environment; Educational Facilities; Educational Finance; *Educational History; Federal Government; Foreign Countries; Government School Relationship; Informal Education; Intergenerational Programs; International Cooperation; *International Educational Exchange; *International Organizations; *International Programs; Lifelong Learning; Literacy; Literacy Education; Nonformal Education; Open Education; Organizational Change; Partnerships