The State of Disaster Risk Reduction in Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Final Thesis Coughlin.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY UNDERSTANDING THE SPREAD OF ISIS IN IRAQ WILLIAM D. COUGHLIN SPRING 2016 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Geography and International Politics with honors in Geography Reviewed and approved* by the following: Rodger Downs Professor of Geography Honors Advisor and Thesis Supervisor Donna Peuquet Professor of Geography Faculty Reader * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) first took control of territory in Iraq in 2013 and the group has continued to expand its control and influence despite international intervention. The rise of ISIS was unexpected and unprecedented, and there continues to be a lack of understanding of how ISIS was able to gain a large amount of territory in such a short amount of time. This paper aims to establish what the core factors are that allowed ISIS to form, spread and govern territory in Iraq. The ESRI exploratory regression tool was used to create a multivariate regression model and to analyze twelve factors that may play significant roles in the spread of ISIS. The factors that were considered are ethnicity (Sunni, Shia, Kurdish and mixed), water resources, civilian deaths, suicide bombing deaths, distance from Syria, population, location of Iraqi military brigades, and major cities. The final multivariate regression model had Kurdish majority, water resources, civilian deaths, distance from Syria and Iraqi military brigades as significant factors. These five exploratory variables has an R2 of .77, explaining 77% of towns controlled by ISIS. -

PSHP Technical Report Template

GREENHOUSE GAS AND OTHER E NVIRONMENTAL, SOCIAL, AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF HYDROPOWER: A LITERATURE REVIEW CLIMATE ECONOMIC ANALYSIS FOR DEVELOPMENT, INVESTMENT, AND RESILIENCE (CEADIR) March 13, 2019 This report was made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by Crown Agents-USA and Abt Associates. Recommended Citation: Manion, Michelle; Eric Hyman; Jason Vogel; David Cooley; Gordon Smith. 2019. Greenhouse Gas and Other Environmental, Social, and Economic Impacts of Hydropower: A Literature Review. Washington, DC: Crown Agents-USA and Abt Associates, Prepared for the U.S. Agency for International Development. Front photo source: Itaipu Dam in Brazil, taken by International Hydropower Association on July 8, 2011, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8e/Itaipu_Aerea.jpg Crown Agents USA Ltd. 1 1129 20th Street NW 1 Suite 500 1 Washington, DC 20036 1 T. (202) 822-8052 1 www.crownagentsusa.com With: Abt Associates Inc. GREENHOUSE GAS AND OTHER ENVIRONMENTAL, SOCIAL, AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF HYDROPOWER: A LITERATURE REVIEW CLIMATE ECONOMIC ANALYSIS FOR DEVELOPMENT, INVESTMENT, AND RESILIENCE (CEADIR) Contract No.: AID-OAA-I-12-00038 Task Order: AID-OAA-TO-14-00007 Economic Policy Office and Global Climate Change Office Bureau for Economic Growth, Education and Environment U.S. Agency for International Development 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20523 Prepared by: Michelle Manion (Abt Associates) Eric Hyman (USAID) Jason Vogel (Abt Associates) David Cooley (Abt Associates), and Gordon Smith (Crown Agents-USA) March 13, 2019 DISCLAIMER This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). -

Country of Origin Information Iraq

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION IRAQ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) October 2005 This report has been produced by UNHCR on the basis of information obtained from a variety of publicly available sources, analyses and comments. The purpose of the report is to serve as a reference for a breadth of country of origin information and thereby assists, inter alia, in the asylum determination process and when assessing the feasibility of returns to Iraq in safety and dignity. The information contained does not purport to be exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, and incomplete, inaccurate or incorrect information cannot be ruled out. The inclusion of information in this report does not constitute an endorsement of the information or views of third parties. Neither does such information necessarily represent statements of policy or views of UNHCR or the United Nations. In particular the use of ethnic-sectarian terms such as ‘Shiite’, ‘Sunni’ or ‘Kurd’ does not constitute an endorsement of sectarianism but merely reflects the current realities on the ground (i.e. these groups should not be considered homogenous entities). ii Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................ III LIST OF ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................VII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 1 A. INTRODUCTION -

Measuring Security and Stability in Iraq

MMMeeeaaasssuuurrriiinnnggg SSStttaaabbbiiillliiitttyyy aaannnddd SSSeeecccuuurrriiittyyy iiinnn IIIrrraaaqqq December 2007 Report to Congress In accordance with the Department of Defense Appropriations Act 2007 (Section 9010, Public Law 109-289) Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... iii 1. Stability and Security in Iraq .................................................................................................1 1.1. Political Stability......................................................................................................1 National Reconciliation...........................................................................................1 Political Commitments.............................................................................................1 Government Reform ................................................................................................3 Transnational Issues.................................................................................................5 1.2. Economic Activity...................................................................................................8 Budget Execution.....................................................................................................8 IMF Stand-By Arrangement and Debt Relief..........................................................9 Indicators of Economic Activity..............................................................................9 -

'Because We Struggle to Survive'

“Because we struggle to survive” Child Labour among Refugees of the Syrian Conflict Child Labour Report 2016 Disclaimer terre des hommes Siège | Hauptsitz | Sede | Headquarters Avenue de Montchoisi 15, CH-1006 Lausanne T +41 58 611 06 66, F +41 58 611 06 77 E-mail : [email protected], CCP : 10-11504-8 Research support: Ornella Barros, Dr. Beate Scherrer, Angela Großmann Authors: Barbara Küppers, Antje Ruhmann Photos : Front cover, S. 13, 37: Servet Dilber S. 3, 8, 12, 21, 22, 24, 27, 47: Ollivier Girard S. 3: Terre des Hommes International Federation S. 3: Christel Kovermann S. 5, 15: Terre des Hommes Netherlands S. 7: Helmut Steinkeller S. 10, 30, 38, 40: Kerem Yucel S. 33: Terre des hommes Italy The study at hand is part of a series published by terre des hommes Germany annually on 12 June, the World Day against Child Labour. We would like to thank terre des hommes Germany for their excellent work, as well as Terre des hommes Italy and Terre des Hommes Netherlands for their contributions to the study. We would also like to thank our employees, especially in the Middle East and in Europe for their contributions to the study itself, as well as to the work of editing and translating it. Terre des hommes (Lausanne) is a member of the Terre des Hommes International Federation (TDHIF) that brings together partner organisations in Switzerland and in other countries. TDHIF repesents its members at an international and European level. First published by terre des hommes Germany in English and German, June 2016. -

The Case of the Iraqi Disputed Territories Declaration Submitted By

Title: Education as an Ethnic Defence Strategy: The Case of the Iraqi Disputed Territories Declaration Submitted by Kelsey Jayne Shanks to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics, October 2013. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Kelsey Shanks ................................................................................. 1 Abstract The oil-rich northern districts of Iraq were long considered a reflection of the country with a diversity of ethnic and religious groups; Arabs, Turkmen, Kurds, Assyrians, and Yezidi, living together and portraying Iraq’s demographic makeup. However, the Ba’ath party’s brutal policy of Arabisation in the twentieth century created a false demographic and instigated the escalation of identity politics. Consequently, the region is currently highly contested with the disputed territories consisting of 15 districts stretching across four northern governorates and curving from the Syrian to Iranian borders. The official contest over the regions administration has resulted in a tug-of-war between Baghdad and Erbil that has frequently stalled the Iraqi political system. Subsequently, across the region, minority groups have been pulled into a clash over demographic composition as each disputed districts faces ethnically defined claims. The ethnic basis to territorial claims has amplified the discourse over linguistic presence, cultural representation and minority rights; and the insecure environment, in which sectarian based attacks are frequent, has elevated debates over territorial representation to the height of ethnic survival issues. -

Profile: Tigris/Euphrates River Basins

va®aea wi air- tf< ti +f' 1> t } r Profile: Tigris/Euphrates River Basins it III 4 M .1 I J CEWRC-IWR-P 29 May 91 Tigris-Euphrates Basin Summary *Projects in Turkey, Syria, and Iraq are expected to greatly reduce both Euphrates and Tigris stream flows and reduce water quality *Already Syria claims Tabqa Damhydropowerplants are operating at only 10%capacitybecause ofAtaturk filling *Estimates of depletion vary; one estimate is for approx. 50 % depletion of Euphrates flowsby Turkey and almost a 30 % depletionby Syria(given completionofTurkey's Gap project and projected Syrian withdrawals); the most likely date for completion of all projects (if at all) is 2040; in the 1960s, Iraq withdrew an average of about 50 % of Euphrates flows *One estimate of projected Euphrates depletions for the year 2000 is 20 % each by Turkey and Syria *Syria and Iraq may be especially affected by reduced flow during low flow years *Of more immediate concern than possible long-term reduction in flow quantity is increased pollution of inflows to Lake Assad on the Euphrates (main water supply source for Aleppo) and to the Khabur River (both in Syria) owing to irrigation return flows; both areas plan for greater use of those waters *Quality of Euphrates flows into Iraq will also beaffected *Iraq has constructed Tigris-Euphrates Outfall Drain to drain irrigation water into Shatt al-Basra and Gulf *Most water withdrawals within the basin are forirrigation;Turkey,Syria,and Iraq all are attempting to expand irrigation programs *Recent projected demands for water withdrawals for Iraq were not available for this study. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series WAT2018-2546

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: LNG2014-1176 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series WAT2018-2546 Geological and Geotechnical Study of Badush Dam, Iraq Varoujan Sissakian Lecturer University of Kurdistan Iraq Nasrat Adamo Consultant Lulea University of Technology Sweden Nadhir Al-Ansari Professor Lulea University of Technology Sweden Sven Knutsson Professor Lulea University of Technology Sweden Jan Laue Professor Lulea University of Technology Sweden 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: WAT2018-2546 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series Conference papers are research/policy papers written and presented by academics at one of ATINER’s academic events. ATINER’s association started to publish this conference paper series in 2012. All published conference papers go through an initial peer review aiming at disseminating and improving the ideas expressed in each work. Authors welcome comments. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research This paper should be cited as follows: Sissakian, V., Adamo, N., Al-Ansari, N., Knutsson, S. and Laue, S. (2018). "Geological and Geotechnical Study of Badush Dam, Iraq", Athens: ATINER'S Conference Paper Series, No: WAT2018-2546. Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN: 2241-2891 27/09/2018 2 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: WAT2018-2546 Geological and Geotechnical Study of Badush Dam, Iraq Varoujan Sissakian Nasrat Adamo Nadhir Al-Ansari Sven Knutsson Jan Laue Abstract Badush Dam is a combined earthfill and concrete buttress dam; uncompleted, it is planned to be a protection dam downstream of Mosul Dam, which impounds the Tigris River. -

Badush Dam: Controversy and Future Possibilities

Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering, vol . 8, no. 2, 2018, 17-33 ISSN: 1792-9040 (print version), 1792-9660 (online) Scienpress Ltd, 2018 Badush Dam: Controversy and Future Possibilities Nasrat Adamo1, Varoujan K. Sissakian2, Nadhir Al-Ansari1, Sven Knutsson1and Jan Laue1 Abstract Badush Dam is believed to be the first dam in the world which is designed to protect from the flood wave which could result from the collapse of another dam; in this case Mosul Dam. Badush Dam construction was started in 1988 but it was stopped two years later due to unexpected reasons. From that time on many attempts were made to resume construction without success. Its value was stressed in a multitude of studies and technical reports amid conflict of opinions on how to do this. The original design of the dam as a protection dam was intended to have a large part of the reservoir empty to accommodate the volume of the expected flood wave for only a few months during which time it’s content are released in a controlled and safe way to the downstream. The lower part of Badush Dam which has a limited height continues before and after this event to act as a low head power generation facility. Among the later studies on the dam, there were suggestions to introduce changes to the design of the unfinished dam which covered the foundation treatment and also asked for constructing a diaphragm in the dam. A long controversy is still going on with many possibilities but with no hope to reach a final solution soon. -

IRAQ, YEAR 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

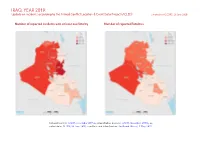

IRAQ, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 IRAQ, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 1282 452 1253 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2019 2 Protests 845 12 72 Battles 719 541 1735 Methodology 3 Riots 242 72 390 Conflict incidents per province 4 Violence against civilians 191 136 240 Strategic developments 190 6 7 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 3469 1219 3697 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 IRAQ, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

INTERNATIONAL WATERS of the MIDDLE EAST from EUPHRATES-TIGRIS to NILE

'p MIN INTERNATIONAL WATERS of the MIDDLE EAST FROM EUPHRATES-TIGRIS TO NILE WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SERIES WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SERtES 2 International Waters of the Middle East From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile Water Resources Management Series I. Water for Sustainable Development in the Twenty-first Century edited by ASIT K. BIswAs, MOHAMMED JELLALI AND GLENN STOUT International Waters of the Middle East: From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile edited by ASIT K. BlswAs Management and Development of Major Rivers edited by ALY M. SHADY, MOHAMED EL-MOTTASSEM, ESSAM ALY ABDEL-HAFIZ AND AsIT K. BIswAs WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SERIES : 2 International Waters of the Middle East From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile Edited b' ASIT K. BISWAS Sponsored by United Nations University International Water Resources Association With the support of Sasakawa Peace Foundation United Nations Entne4rogramme' '4RY 1' Am ir THE SASAKAWA PEACE FOUNDATION OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS BOMBAY DELHi CALCUTTA MADRAS 1994 Oxford University Press, Walton Street, Oxford 0X2 6DP Oxford New York Toronto Delhi Bombay Calcutta Madras Karachi KualaLumpur Singapore Hong Kong Tokyo Nairobi Dar esSalaam Cape Town Melbourne Auckland Madrid anji.ssocia:es in Berlin Ibadan First published 1994 © United Nations University, International Water Resources Association, Sasakawa Peace Foundation and United Nations Environ,nent Programme, 1994 ISBN 0 19 563557 4 Printed in India Typeset by Alliance Phototypesetters, Pondicherry 605 013 Printed at Rajkamal Electric Press, Delhi 110 033 Published by Neil O'Brien, Oxford University Press YMCA Library Building, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 110 001 This hook is dedicated to DR TAKASHI SHIRASU as a mark of esteem for his contributions to peace and a token of true regard for a friend Contents List of Contributors IX Series Preface xi Preface Xiii I. -

The Civilian Youth and Time of Crisis a Field Research in the Sociology of Living in a Various Civilian/Local Society(Mosul City As a Field Study)

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 09, 2020 THE CIVILIAN YOUTH AND TIME OF CRISIS A FIELD RESEARCH IN THE SOCIOLOGY OF LIVING IN A VARIOUS CIVILIAN/LOCAL SOCIETY(MOSUL CITY AS A FIELD STUDY) Asst.Prof. Dr. HasanJassim Rashid University of Mosul,College of Arts,Department of Sociology,Mosul, Iraq E-mail:[email protected] Civil Youth and Time of Crisis: Participatory Research With A Group of Students from the Department of Sociology to Know the Sociology of Living in a Diverse Community/Iraqi City of Mosul as Field of the Study. Received: 08.03.2020 Revised: 25.04.2020 Accepted: 14.05.2020 Abstract Young people are the mainstay of society, not only in terms of continuity in human existence, but also as a continuation of social thought, so they must be involved in finding solutions to those problems that affect their communities, such as Isis's control of Nineveh province and its center "the city of Mosul", which is socially and culturally heterogeneous. Therefore, these young people are the means and the goal in their view of this conflict and how to contribute to the mitigation of its results. The young people here are participants and through the experimental participation of questions and the distribution of those questions and answering them we can know their point of view about ISIS's control over their regions and the disadvantages of that control in what concerns civil liberties and its behaviors and the prevention of communication and interaction with others who belong to different cultural identity to create national distinction in difficult circumstances that their society passed through in ascending stages started from an epicenter of political crisis and then there were some automatic factors that helped to aggravate the situation with a favorable conditions till the crisis reached a stage of tension and anxiety then came the calm that precedes the storm.