Country of Origin Information Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah by Michael Knights May 25, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Michael Knights Michael Knights is the Boston-based Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow of The Washington Institute, specializing in the military and security affairs of Iraq, Iran, and the Persian Gulf states. Articles & Testimony The campaign is Iraq's latest attempt to push militia and coalition forces into a single battlespace, and lessons from past efforts have seemingly improved their tactics. n May 22, the Iraqi government announced the opening of the long-awaited battle of Fallujah, the city only O 30 miles west of Baghdad that has been fully under the control of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant group for the past 29 months. Fallujah was a critical hub for al-Qaeda in Iraq and later ISIL in the decade before ISIL's January 2014 takeover. On the one hand it may seem surprising that Fallujah has not been liberated sooner -- after all, it has been the ISIL- controlled city closest to Baghdad for more than two years. The initial reason was that there was always something more urgent to do with Iraq's security forces. In January 2014, the Iraqi security forces were focused on preventing an ISIL takeover of Ramadi next door. The effort to retake Fallujah was judged to require detailed planning, and a hasty counterattack seemed like a pointless risk. In retrospect it may have been worth an early attempt to break up ISIL's control of the city while it was still incomplete. -

Blood and Ballots the Effect of Violence on Voting Behavior in Iraq

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv DEPTARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BLOOD AND BALLOTS THE EFFECT OF VIOLENCE ON VOTING BEHAVIOR IN IRAQ Amer Naji Master’s Thesis: 30 higher education credits Programme: Master’s Programme in Political Science Date: Spring 2016 Supervisor: Andreas Bågenholm Words: 14391 Abstract Iraq is a very diverse country, both ethnically and religiously, and its political system is characterized by severe polarization along ethno-sectarian loyalties. Since 2003, the country suffered from persistent indiscriminating terrorism and communal violence. Previous literature has rarely connected violence to election in Iraq. I argue that violence is responsible for the increases of within group cohesion and distrust towards people from other groups, resulting in politicization of the ethno-sectarian identities i.e. making ethno-sectarian parties more preferable than secular ones. This study is based on a unique dataset that includes civil terror casualties one year before election, the results of the four general elections of January 30th, and December 15th, 2005, March 7th, 2010 and April 30th, 2014 as well as demographic and socioeconomic indicators on the provincial level. Employing panel data analysis, the results show that Iraqi people are sensitive to violence and it has a very negative effect on vote share of secular parties. Also, terrorism has different degrees of effect on different groups. The Sunni Arabs are the most sensitive group. They change their electoral preference in response to the level of violence. 2 Acknowledgement I would first like to thank my advisor Dr. -

House Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JUNE 21, 2005 No. 83 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was I would like to read an e-mail that there has never been a worse time for called to order by the Speaker pro tem- one of my staffers received at the end Congress to be part of a campaign pore (Miss MCMORRIS). of last week from a friend of hers cur- against public broadcasting. We formed f rently serving in Iraq. The soldier says: the Public Broadcasting Caucus 5 years ‘‘I know there are growing doubts, ago here on Capitol Hill to help pro- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO questions and concerns by many re- mote the exchange of ideas sur- TEMPORE garding our presence here and how long rounding public broadcasting, to help The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- we should stay. For what it is worth, equip staff and Members of Congress to fore the House the following commu- the attachment hopefully tells you deal with the issues that surround that nication from the Speaker: why we are trying to make a positive important service. difference in this country’s future.’’ There are complexities in areas of le- WASHINGTON, DC, This is the attachment, Madam June 21, 2005. gitimate disagreement and technical I hereby appoint the Honorable CATHY Speaker, and a picture truly is worth matters, make no mistake about it, MCMORRIS to act as Speaker pro tempore on 1,000 words. -

Three Generations of Jihadism in Iraqi Kurdistan

Notes de l’Ifri Three Generations of Jihadism in Iraqi Kurdistan Adel BAKAWAN July 2017 Turkey/ Middle East Program In France, the French Institute of International Relations (Ifri) is the leading independent research, information and debate centre on major international issues. Ifri was founded in 1979 by Thierry Montbrial, and is an officially recognised non-profit organisation (Law of 1901). It is not subject to any government supervision, freely defines its own research agenda and regularly publishes its work. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together international policy-makers and experts through its research and debates Along with its office in Brussels (Ifri-Brussels), Ifri is one of the few French think tanks to position itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not reflect the official views of their institutions. ISBN: 978-2-36567-743-1 © All right reserved, Ifri, 2017 Cover: © padchas/Shutterstock.com How to quote this publication: Adel Bakawan, “Three Generations of Jihadism in Iraqi Kurdistan”, Notes de l’Ifri, Ifri, July 2017. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE Tel.: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 – Fax: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Email: [email protected] Ifri-Bruxelles Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 1000 – Brussels – BELGIUM Tel.: +32 (0)2 238 51 10 – Fax: +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Author Adel Bakawan is a sociologist, associate researcher at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS, in French) in Paris, and the Centre for Sociological Analysis and Intervention (CADIS, in French). -

5. Kurdish Tribes

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Blood feuds Version 1.0 August 2017 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information COI in this note has been researched in accordance with principles set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI) and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, namely taking into account its relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability. All information is carefully selected from generally reliable, publicly accessible sources or is information that can be made publicly available. Full publication details of supporting documentation are provided in footnotes. Multiple sourcing is normally used to ensure that the information is accurate, balanced and corroborated, and that a comprehensive and up-to-date picture at the time of publication is provided. Information is compared and contrasted, whenever possible, to provide a range of views and opinions. -

Report Iraq: Travel Documents and Other Identity Documents

l Report Iraq: Travel documents and other identity documents Report Iraq: Travel documents and other identity documents LANDINFO –16DECEMBER 2015 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2016 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

Mcallister Bradley J 201105 P

REVOLUTIONARY NETWORKS? AN ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN IN TERRORIST GROUPS by Bradley J. McAllister (Under the Direction of Sherry Lowrance) ABSTRACT This dissertation is simultaneously an exercise in theory testing and theory generation. Firstly, it is an empirical test of the means-oriented netwar theory, which asserts that distributed networks represent superior organizational designs for violent activists than do classic hierarchies. Secondly, this piece uses the ends-oriented theory of revolutionary terror to generate an alternative means-oriented theory of terrorist organization, which emphasizes the need of terrorist groups to centralize their operations. By focusing on the ends of terrorism, this study is able to generate a series of metrics of organizational performance against which the competing theories of organizational design can be measured. The findings show that terrorist groups that decentralize their operations continually lose ground, not only to government counter-terror and counter-insurgent campaigns, but also to rival organizations that are better able to take advantage of their respective operational environments. However, evidence also suggests that groups facing decline due to decentralization can offset their inability to perform complex tasks by emphasizing the material benefits of radical activism. INDEX WORDS: Terrorism, Organized Crime, Counter-Terrorism, Counter-Insurgency, Networks, Netwar, Revolution, al-Qaeda in Iraq, Mahdi Army, Abu Sayyaf, Iraq, Philippines REVOLUTIONARY NETWORK0S? AN ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN IN TERRORIST GROUPS by BRADLEY J MCALLISTER B.A., Southwestern University, 1999 M.A., The University of Leeds, United Kingdom, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY ATHENS, GA 2011 2011 Bradley J. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 2005 No. 143 House of Representatives The House met at 2 p.m. MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE have three grown daughters and seven The Reverend Bruce Bigelow, Pastor, A message from the Senate by Ms. grandchildren, all who reside in Indi- Lake Hills Baptist Church, Scherer- Curtis, one of its clerks, announced ana. ville, Indiana, offered the following that the Senate has passed a concur- Let us hope the words of his inspiring prayer: rent resolution of the following title in prayer will remain with us and his Our Lord, we come before Thee and which the concurrence of the House is dedication to the ministry will always we gather together to do business, to requested: be appreciated. do business for this Nation and for Thee. We have sought to follow Thee. S. Con. Res. 56. Concurrent resolution ex- f pressing appreciation for the contribution of You have said feed the hungry, and we Chinese art and culture and recognizing the EMINENT DOMAIN have fed the hungry. You have said Festival of China at the Kennedy Center. give drink to those that are thirsty, (Ms. FOXX asked and was given per- f and we have given drink. We have mission to address the House for 1 blessed others abundantly because You WELCOMING THE REVEREND minute.) have blessed us as a Nation in great BRUCE BIGELOW Ms. FOXX. Mr. Speaker, last June, in abundance. -

Iraqi Kurdistan News in Brief Political Yazidi

Iraqi Kurdistan News in brief Political Yazidi Kurds’ mass grave found in western Mosul Source: NRT TV 1st of Jun 2015 Nineveh – Erbil: Bodies of 80 Yazidi Kurds was found in mass grave in western part of the Iraqi northern city of Mosul, official said. The official to follow Yazidi affairs in Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), Hadi Dobani, told NRT that 80 Yazidi bodies, including 33 children and 20 women, were found in Badosh, western Mosul. He told NRT that the bodies might have been buried by the militants of the Islamic State (IS) during its attack onto the region in August 2014. Dobani said findings showed torture on parts of the body and gun shots in the heads of the victims. It is further to mention that more than 11 mass graves have been found in the region after retaking there from the control of IS. Kurdistan receives Iraq’s Anbar refugees through air and land Source: Hawler newspaper 1st of Jun 2015 Erbil: Baghdad Airport released a statement reading that Iraqi airways transported displaced Anbar people to Kurdistan region airports free of charge. Meanwhile, the regional Office of the Ministry of Displacement and Migration announced on Sunday that the Kurdistan capital city of Erbil receives daily about 500 displaced families coming from Baghdad by air. This figure was announced by Aliah Bazzaz, Director of the Regional Office of the Ministry of Displacement and Migration in the Iraqi Kurdistan region and gave this statement to Hawler newspaper. Braham Salih: “Motto would not realize Kurdish independence” Source: PUKMEDIA 2nd of June, 2015 Slemani: The deputy leader of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), former Kurdistan PM, Braham Salih, asked for close ties between parties in Kurdistan Region and solving intra-PUK tensions and stressed the Kurdish region’s independence is impossible with motto. -

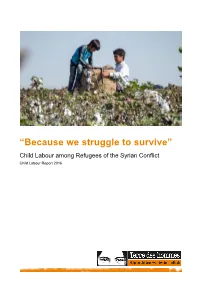

'Because We Struggle to Survive'

“Because we struggle to survive” Child Labour among Refugees of the Syrian Conflict Child Labour Report 2016 Disclaimer terre des hommes Siège | Hauptsitz | Sede | Headquarters Avenue de Montchoisi 15, CH-1006 Lausanne T +41 58 611 06 66, F +41 58 611 06 77 E-mail : [email protected], CCP : 10-11504-8 Research support: Ornella Barros, Dr. Beate Scherrer, Angela Großmann Authors: Barbara Küppers, Antje Ruhmann Photos : Front cover, S. 13, 37: Servet Dilber S. 3, 8, 12, 21, 22, 24, 27, 47: Ollivier Girard S. 3: Terre des Hommes International Federation S. 3: Christel Kovermann S. 5, 15: Terre des Hommes Netherlands S. 7: Helmut Steinkeller S. 10, 30, 38, 40: Kerem Yucel S. 33: Terre des hommes Italy The study at hand is part of a series published by terre des hommes Germany annually on 12 June, the World Day against Child Labour. We would like to thank terre des hommes Germany for their excellent work, as well as Terre des hommes Italy and Terre des Hommes Netherlands for their contributions to the study. We would also like to thank our employees, especially in the Middle East and in Europe for their contributions to the study itself, as well as to the work of editing and translating it. Terre des hommes (Lausanne) is a member of the Terre des Hommes International Federation (TDHIF) that brings together partner organisations in Switzerland and in other countries. TDHIF repesents its members at an international and European level. First published by terre des hommes Germany in English and German, June 2016. -

The Case of the Iraqi Disputed Territories Declaration Submitted By

Title: Education as an Ethnic Defence Strategy: The Case of the Iraqi Disputed Territories Declaration Submitted by Kelsey Jayne Shanks to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics, October 2013. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Kelsey Shanks ................................................................................. 1 Abstract The oil-rich northern districts of Iraq were long considered a reflection of the country with a diversity of ethnic and religious groups; Arabs, Turkmen, Kurds, Assyrians, and Yezidi, living together and portraying Iraq’s demographic makeup. However, the Ba’ath party’s brutal policy of Arabisation in the twentieth century created a false demographic and instigated the escalation of identity politics. Consequently, the region is currently highly contested with the disputed territories consisting of 15 districts stretching across four northern governorates and curving from the Syrian to Iranian borders. The official contest over the regions administration has resulted in a tug-of-war between Baghdad and Erbil that has frequently stalled the Iraqi political system. Subsequently, across the region, minority groups have been pulled into a clash over demographic composition as each disputed districts faces ethnically defined claims. The ethnic basis to territorial claims has amplified the discourse over linguistic presence, cultural representation and minority rights; and the insecure environment, in which sectarian based attacks are frequent, has elevated debates over territorial representation to the height of ethnic survival issues. -

Kurdish Islamists in Iraq 5

5 Kurdish Islamists in Iraq from the MuslimBrotherhood to the So-Called Islamic State: Shaban 1436 June 2015 Continuity or Departure? Mohammed Shareef Visiting Lecturer, Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, University of Exeter Kurdish Islamists in Iraq from the Muslim Brotherhood to the So-Called Islamic State: Continuity or Departure? Mohammed Shareef Visiting Lecturer, Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, University of Exeter العدد - )اﻷول( 4 No. 5 June 2015 © King Faisal Center for research and Islamic Studies, 2015 King Fahd National Library Catalging-In-Publication Data King Faisal Center for research and Islamic Studies Dirasat: Kurdish Islamists in Iraq from the Muslim Brotherhood to the So-Called Islamic State: Continuity or Departure? / King Faisal Center for research and Islamic Studies - Riyadh, 2015 p 44; 16.5x23cm (Dirasat; 5) ISBN: 978-603-8032-65-7 1- Kurds - Iraq - Politics and government - History I- Title 956 dc 1436/6051 L.D. no. 1436/7051 ISBN: 978-603-8032-65-7 Designer: Azhari Elneiri Disclaimer: This paper and its contents reflect the author’s analyses and opinions. Views and opinions contained herein are the author’s and should not be attributed to any officials affiliated with the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies or any Saudi Arabian national. The author is solely responsible for any errors that remain in the document. Table of Contents Abstract 5 Introduction 7 Kurdish Islamist Parties and the So-Called Islamic State 10 The Muslim Brotherhood and the Beginnings of Islamism in Kurdistan 13 The Emergence of Indigenous Kurdish Islamist Groups 19 The Islamic Movement of Kurdistan and Ansar al-Islam after 1991 27 Kurds in the So-Called Islamic State 35 Bibliography 39 Author Biography 40 3 4 No.