The Quarry As Sculpture: the Place of Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approval of Minutes: Election of Officers: Sarah

BAKER CITY PUBLIC ARTS COMMISSION APPROVED MINUTES July 9, 2019 ROLL CALL: The meeting was called to order at 5:40 p.m. Present were: Ann Mehaffy, Lynette Perry, Corrine Vetger, Kate Reid, Fred Warner, Jr., Robin Nudd and guest Dean Reganess. APPROVAL OF Lynette moved to approve the June minutes as presented. Corrine MINUTES: seconded the motion. Motion carried. ELECTION OF Ann questioned if she and Corrine could serve as co-chairs. Robin OFFICERS: would check into it and let them know at next meeting. SARAH FRY PROJECT Ann reported that the pieces were being stored in the basement at UPDATE: City Hall. Ann would check with Molly to see if she had heard back on timeline for repairs to brickwork at the Corner Brick building. ART ON LOAN: Corrine stated that she would reach out to Shawn. SHAWN PETERSON PROJECT UPDATE: VINYL WRAP Nothing new to report on the project with ODOT. UPDATE: OTHER BUSINESS: Dean Reganess was present and visited with group regarding his trade: stone masonry. Dean is a third generation stone mason and had recently relocated to Baker City. Dean announced that he wanted to offer his help in the community and discussed creating a large community stone sculpture that could be pinned together. Dean also discussed stone benches with an estimated cost of $1200/each. Dean mentioned that a film crew would be coming from San Antonio and thought the exposure might be good for Baker. Corrine questioned if Dean had ideas to help the Public Arts Commission raise funds for public art. Dean mentioned that he would be willing to create a mold/casting of something that depicted Baker and it could be recreated and sold to raise funds. -

Notes on the Parish of Mylor, Cornwall

C.i i ^v /- NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR /v\. (crt MVI.OK CII r RCII. -SO UIH I'OKCil AND CROSS O !• ST. MlLoKIS. [NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR CORNWALL. BY HUGH P. OLIVEY M.R.C.S. Uaunton BARNICOTT &- PEARCE, ATHEN^UM PRESS 1907 BARNICOTT AND PEARCE PRINTERS Preface. T is usual to write something as a preface, and this generally appears to be to make some excuse for having written at all. In a pre- face to Tom Toole and his Friends — a very interesting book published a few years ago, by Mrs. Henry Sandford, in which the poets Coleridge and Wordsworth, together with the Wedgwoods and many other eminent men of that day figure,—the author says, on one occasion, when surrounded by old letters, note books, etc., an old and faithful servant remon- " " strated with her thus : And what for ? she " demanded very emphatically. There's many a hundred dozen books already as nobody ever reads." Her hook certainly justified her efforts, and needed no excuse. But what shall I say of this } What for do 1 launch this little book, which only refers to the parish ot Mylor ^ vi Preface. The great majority of us are convinced that the county of our birth is the best part of Eng- land, and if we are folk country-born, that our parish is the most favoured spot in it. With something of this idea prompting me, I have en- deavoured to look up all available information and documents, and elaborate such by personal recollections and by reference to authorities. -

Sculpture Northwest Nov/Dec 2015 Ssociation a Nside: I “Conversations” Why Do You Carve? Barbara Davidson Bill Weissinger Doug Wiltshire Victor Picou Culptors

Sculpture NorthWest Nov/Dec 2015 ssociation A nside: I “Conversations” Why Do You Carve? Barbara Davidson Bill Weissinger Doug Wiltshire Victor Picou culptors S Stone Carving Videos “Threshold” Public Art by: Brian Goldbloom tone S est W t Brian Goldbloom: orth ‘Threshold’ (Detail, one of four Vine Maple column wraps), 8 feet high and 14 N inches thick, Granite Sculpture NorthWest is published every two months by NWSSA, NorthWest Stone Sculptors Association, a In This Issue Washington State Non-Profit Professional Organization. Letter From The President ... 3 CONTACT P.O. Box 27364 • Seattle, WA 98165-1864 FAX: (206) 523-9280 Letter From The Editors ... 3 Website: www.nwssa.org General e-mail: [email protected] “Conversations”: Why Do We Carve? ... 4 NWSSA BOARD OFFICERS Carl Nelson, President, (425) 252-6812 Ken Barnes, Vice President, (206) 328-5888 Michael Yeaman, Treasurer, (360) 376-7004 Verena Schwippert, Secretary, (360) 435-8849 NWSSA BOARD Pat Barton, (425) 643-0756 Rick Johnson, (360) 379-9498 Ben Mefford, (425) 943-0215 Steve Sandry, (425) 830-1552 Doug Wiltshire, (503) 890-0749 PRODUCTION STAFF Penelope Crittenden, Co-editor, (541) 324-8375 Lane Tompkins, Co-editor, (360) 320-8597 Stone Carving Videos ... 6 DESIGNER AND PRINTER Nannette Davis of QIVU Graphics, (425) 485-5570 WEBMASTER Carl Nelson [email protected] 425-252-6812 Membership...................................................$45/yr. Subscription (only)........................................$30/yr. ‘Threshold’, Public Art by Brian Goldbloom ... 10 Please Note: Only full memberships at $45/yr. include voting privileges and discounted member rates at symposia and workshops. MISSION STATEMENT The purpose of the NWSSA’s Sculpture NorthWest Journal is to promote, educate, and inform about stone sculpture, and to share experiences in the appreciation and execution of stone sculpture. -

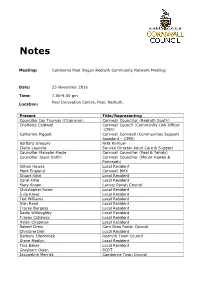

Camborne Pool Illogan Redruth Community Network Meeting Date

Notes Meeting: Camborne Pool Illogan Redruth Community Network Meeting Date: 23 November 2016 Time: 7.00-9.00 pm Pool Innovation Centre, Pool, Redruth. Location: Present Title/Representing Councillor Ian Thomas (Chairman) Cornwall Councillor (Redruth South) Charlotte Caldwell Cornwall Council (Community Link Officer -CPIR) Catherine Piggott Cornwall Cornwall (Communities Support Assistant – CPIR) Barbara Gregory NHS Kernow Claire Leandro Service Director Adult Care & Support Councillor Malcolm Moyle Cornwall Councillor (Pool & Tehidy) Councillor Joyce Duffin Cornwall Councillor (Mount Hawke & Portreath) Gillian Howes Local Resident Mark England Cornwall BMX Stuart Kitto Local Resident Carol Kitto Local Resident Mary Anson Lanner Parish Council Christopher Rowe Local Resident Julia Rowe Local Resident Ted Williams Local Resident Alan Reed Local Resident Tracey Burgess Local Resident Sadie Willoughby Local Resident Tracey Callaway Local Resident Helen Chapman Local Resident Robert Drew Carn Brea Parish Council Christine Deli Local Resident Barbara Ellenbroek Redruth Town Council Steve Medlyn Local Resident Tina Baker Local Resident Grayburn Owen PCDT Jacqueline Merrick Camborne Town Council Neal Chambers NHS Kernow Terry Stanton Local Resident Tim Sutton Local Resident Stevio Sutton Local Resident Zoe Fox Camborne Town Council Apologies for absence: Councillor Mark Kaczmarek, Councillor Paul White, Councillor David Ekinsmyth, Councillor Jude Robinson, Councillor Mike Eddowes, Ivor Corkell, Mel Martin, Anne-Marie Young, Peter Sheppard, Illogan Parish Council, Amanda Mugford (Camborne Town Council), George Le Hunte, Allister Young, Deborah Tritton, Sally Piper, Portreath Parish Council, Bev Price, Kirsty Hickson. Item Key/Action Points Log Number (Action by) 1 Welcome Introductions & Apologies. The Chair welcomed everyone to the meeting. 2 Presentation on the Sustainability & Transformation Plan for Cornwall & Isles of Scilly (NHS & Social Care) See presentation. -

CORNWALL. [.I.Jlllly'

1264. r.AB CORNWALL. [.I.JllLLY'. FARMERs-continued. Matthew Thos. Church town, Tresmere, Meager H.St. Blazey, Par Station R.S.O Martin John, Kingscombe, Linkinhorne, Launceston Meager S. St. Blazey, Par Station RS.O Callington RS.O Matthews Thomas & Son, Blerrick, MeagerTbos. Pengilly, St. Erme, Truro Martin J. Lanyon, Loscombe, Redruth Sheviock, Devonport Medland Mrs. Mary & Sons, Beer, MartinJ.Latchley,Gunnislake,Tavistock Matthews E.Mtdlawn,Pensilva,Liskeard Marhamchurch, Stratton R. S. 0 Martin John, Newton, Callington R.S.O l\Iatthews Mrs.E.Trannaek,Sncrd.Pnznc Medland Henry, Burracott,Poundstock, Martin J.Summercourt,Grampound Rd Matthpws Mrs.George Henry, Chenhale, Stratton R.S.O Martin John, Treneiage, St. Breock, St. Keverne, Helston Medland J. Combe, Herodsfoot, Liskrd )\Tadebridge RS.O Matthews Henry, Winslade, Stoke Medland Richard, Court barton, Mar- Martin J. Trewren, Madron, Penzance Climsland, Callington R.S.O hamchurch, Stratton R.S.O MartinJ.We. moor,Whitstone,Holswrthy Matthews Jas. Nancrossa, Carnmenellis, Medland Thomas, Crethorne, Pound- Martin John, Wishworthy," Lawhitton, Penryn stock, Stratton RS. 0 Launceston MatthewsJohn, Antony, Devonport Medland William, Whiteley, Week St. Martin John Lewis, Treneddon, Lan- Matthews John, Goongillings, Constan- Mary, Stratton RS.O sallos, Polperro RS.O tine, Penryn Medland William, Woodknowle, Mar- Martin In. Symons, Tregavetban, Truro Matthews John, ReJeatb, Camborne hamcburcb, Stratton RS.O Martin J. Albaston,GunnisJake,Tavistck Matthews John, Trendeal, Ladock, Medlen J.Coombe,Duloe,St.KeyneRS.O Martin Joseph, Carnsiddia,St.Stythians, Grampound Road Medlen John, Tbe Glebe, Duloe RS.O Perran-Arworthal R.~.O Mattbews In. Trevorgans, St. Buryan, Medlin M. Cbynoweth, MaOO, Pelll'yn Martin Joseph, Nanpean, St. -

Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

© 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY 41–42 HENDHYSCANS KERNOW 2002–3 EDITORS GRAEME KIRKHAM AND PETER HERRING (Published 2006) CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © COPYRIGHT CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2006 No part of this volume may be reproduced without permission of the Society and the relevant author ISSN 0070 024X Typesetting, printing and binding by Arrowsmith, Bristol © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Contents Preface i HENRIETTA QUINNELL Reflections iii CHARLES THOMAS An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly 1 CHARLES JOHNS Excavation of an Early Christian cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow 80 PRU MANNING and PETER STEAD Journeys to the Rock: archaeological investigations at Tregarrick Farm, Roche 107 DICK COLE and ANDY M JONES Chariots of fire: symbols and motifs on recent Iron Age metalwork finds in Cornwall 144 ANNA TYACKE Cornwall Archaeological Society – Devon Archaeological Society joint symposium 2003: 149 archaeology and the media PETER GATHERCOLE, JANE STANLEY and NICHOLAS THOMAS A medieval cross from Lidwell, Stoke Climsland 161 SAM TURNER Recent work by the Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 165 Recent work in Cornwall by Exeter Archaeology 194 Obituary: R D Penhallurick 198 CHARLES THOMAS © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Preface This double-volume of Cornish Archaeology marks the start of its fifth decade of publication. Your Editors and General Committee considered this milestone an appropriate point to review its presentation and initiate some changes to the style which has served us so well for the last four decades. The genesis of this style, with its hallmark yellow card cover, is described on a following page by our founding Editor, Professor Charles Thomas. -

A Grand Old Country House to Restore in Cornwall

Ref: LCAA6131 Offers over £500,000 Trenoweth House, Crowan, Camborne, Cornwall FREEHOLD A grand old country house to restore in Cornwall. To be sold for the first time in about 25 years; a handsome detached Grade II Listed former vicarage of about 4,600sq.ft. plus a gorgeous detached coach house, both of a rarefied style and grandeur for Cornwall, requiring significant renovation but offering exceptional potential. An opportunity to resurrect a very private and hidden away country house and grounds which are currently overgrown but were once landscaped and extend to about 3⅔ acres. 2 Ref: LCAA6131 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: reception hall, grand study, drawing room, dining room, utility room, rear reception hall, kitchen, back kitchen with apple loft above. First Floor: broad turning staircase and galleried landing, 4 bedrooms, wc, bathroom. Inner landing with staircase to the second floor, vast open-plan vaulted ceilinged studio (potential master bedroom). Second Floor: landing with 2 store rooms off, 4 further bedrooms. Outside: long driveway lined with rhododendrons through wooded overgrown grounds to a large parking area and further parking area beyond in front of the sizeable and handsome COACH HOUSE. Large single storey room attached to the house and overgrown PERIOD BARN, overgrown MODERN OUTBUILDING. Formerly the gardens had an orchard, sweeping lawns and terraces and a pond set within the woodland. In all, about 3⅔ acres. DESCRIPTION Described by its Listed Buildings Register as “a vicarage on a grandiose scale, deliberately asymmetrical in plan and elevations, the varying quality of the architectural detail expressing the functions of the rooms within”. -

JULY 2013 EDITORIAL I Must Admit That I Had a Job Stealing Myself from the Sunshine to Write This

YOUR SUMMER Camelfordian JULY 2013 EDITORIAL I must admit that I had a job stealing myself from the sunshine to write this. I have been trying to grow my own fruit and vege- tables and have found it to be a little more complicated than “shove it in the ground and wait!” My dog has found a cool place to lie in my first ever attempt to grow strawberries and there are only four gooseberries on my prize bush. I shall look forward to harvesting my pea and broad bean in the very near future. I do seem to be very successful at perpetual spinach and lettuce but have managed to kill the mint. I find the biggest pleasure to be lying back with a gin and tonic after I have worked up a sweat and shall continue with this long after I have given up self sufficiency. Don’t forget that there is no in August so you must make this one last! WEBSITE UPDATE We launched the Camelfordian website for the announcement to appear in our June edition. It arrived a little before its time, but has been updated and hopefully improved. You can now click on the thumbnails to bring up copies of the Camel- fordian. Other hyperlinks should now work properly and there is music to accompa- ny some of the pages. It has been checked in Internet Explorer, Firefox, Opera and Google Chrome. However, if you find any problems, any issues with the Website, please let us know. Letter to the editor Dear Editor I would like, through your publication, to express my congratulations to the organisers of the “Street Party” staged on Sunday, 2nd June in Camelford. -

Asfacts July13.Pub

ASFACTS 2013 JULY “H EAT WAVE & H UMIDITY ” I SSUE NEBULA WINNERS ANNOUNCED The 2012 Nebula Awards were presented May 18, 2013, in a ceremony at SFWA’s 48th Annual Nebula Awards Weekend in San Jose, CA. Gene Wolfe was hon- ored with the 2012 Damon Knight Grand Master Award for his lifetime contributions and achievements in the field. A list of winners follows: First Novel: Throne of the Crescent Moon by Saladin Novel: 2312 by Kim Stanley Robinson, Novella: Ahmed, Young Adult Book: Railsea by China Miéville, After the Fall, Before the Fall, During the Fall by Nancy Novella: After the Fall, Before the Fall, During the Fall Kress, Novelette: “Close Encounters” by Andy Duncan, by Nancy Kress, Novelette: “The Girl-Thing Who Went Short Story: “Immersion” by Aliette de Bodard, Ray Out for Sushi” by Pat Cadigan, Short Story: “Immersion” Bradbury Award for Outstanding Dramatic Presentation: by Aliette de Bodard, Anthology: Edge of Infinity edited Beasts of the Southern Wild , and Andre Norton Award by Jonathan Strahan, and Collection: Shoggoths in Bloom for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy Book: Fair by Elizabeth Bear. Coin by E.C. Myers. Non-Fiction: Distrust That Particular Flavor by Carl Sagan and Ginjer Buchanan received Solstice William Gibson, Art Book: Spectrum 19: The Best in Awards, and Michael H. Payne was given the Kevin Contemporary Fantastic Art edited by Cathy Fenner & O’Donnell Jr. Service to SFWA Award. Arnie Fenner, Artist: Michael Whelan, Editor: Ellen Dat- low, Magazine: Asimov’s , and Publisher: Tor. ROGERS & D ENNING HOSTING PRE -CON PARTY RICHARD MATHESON DEAD Patricia Rogers and Scott Denning will uphold a local fannish tradition when they host the Bubonicon 45 LOS ANGELES (Associated Press) -- Richard Pre-Con Party 7:30-10:30 pm Thursday, August 22, at Matheson, the prolific sci-fi and fantasy writer whose I their home in Bernalillo – located at 909 Highway 313. -

CORN"T ALL. [KELLY's

1404 FAR CORN"T ALL. [KELLY's FARMERS continued. Phillips W.Rosenea,Lanliverr,Lostwithl Pomery John, Trethem & Pnlpry, St. Peters John, Kelhelland, Camborne Phillips William John, Bokiddick, Jnst-in-Roseland, Falmonth Peters John, Velandrucia, St. Stythians, Lamvet, Bodmin Pomroy J. Bearland, Callington R.S.O Perranwell Station R.S.O Phillips William John, Lawhibbet, St. Pomroy James, West Redmoor, South Peters John, Windsor Stoke, Stoke Sampsons, Par Station R.S.O hill, Callington R.S.O Climsland, Callington R.S.O Phillips William John, Tregonning, Po:ntingG.Come to Good,PenanwellRSO Peters John, jun. Nancemellan, Kehel- Luxulyan, Lostwithiel Pool John, Penponds, Cam borne land, Camborne Philp Mrs. Amelia, Park Erissey, 'fre- Pooley Henry, Carnhell green, Gwinear, Peters Richard, Lannarth, Redruth leigh, Redruth Camborne Peters S. Gilly vale, Gwennap, Redruth PhilpJn.Belatherick,St.Breward,Bodmin Pooley James,Mount Wise,Carnmenellis, Peters Thomas, Lannarth, Redruth PhilpJ. Colkerrow, Lanlivery ,Lostwithiel Redruth Peters T.J.FourLanes,Loscombe,Redrth Philp J.Harrowbarrow,St.Mellion R.S.O Pooley Wm. Penstraze, Kenwyn, Truro Peters T.Shallow adit, Treleigh,Redruth Philp John, Yolland, Linkinhorne, Cal- Pore Jas. Trescowe, Godolphin, Helston Peters William, Trew1then,St. Stythians, lington R.S.O Pope J. Trescowe, Godolphin, Helston Perranwell Station R.S.O Philp John, jun. Cardwain & Cartowl, Pope Jsph. Trenadrass, St. Erth, Hayle Petherick Thomas, Pempethey, Lante- Pelynt, Duloe R.S.O Pope R. Karly, Jacobstow,StrattonR.S.O glos, Carre1ford Philp Leonard, Downhouse, Stoke Pope William, Lambourne, Perran- Petherick Thomas, Treknow mills, Tin- Climsland, Callingto• R.S.O Zabuloe, Perran-Porth R.S.O tagel, Camelford PhilpRd.CarKeen,St.Teath,Camelford Porter Wm. -

Sculpture and Inscriptions from the Monumental Entrance to the Palatial Complex at Kerkenes DAĞ, Turkey Oi.Uchicago.Edu Ii

oi.uchicago.edu i KERKENES SPECIAL STUDIES 1 SCULPTURE AND INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE MONUMENTAL ENTRANCE TO THE PALATIAL COMPLEX AT KERKENES DAĞ, TURKEY oi.uchicago.edu ii Overlooking the Ancient City on the Kerkenes Dağ from the Northwest. The Palatial Complex is Located at the Center of the Horizon Just to the Right of the Kale oi.uchicago.edu iii KERKENES SPECIAL STUDIES 1 SCULPTURE AND INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE MONUMENTAL ENTRANCE TO THE PALATIAL COMPLEX AT KERKENES DAĞ, TURKEY by CatheRiNe M. DRAyCOTT and GeOffRey D. SuMMeRS with contribution by CLAUDE BRIXHE and Turkish summary translated by G. B∫KE YAZICIO˝LU ORieNTAL iNSTiTuTe PuBLiCATiONS • VOLuMe 135 THe ORieNTAL iNSTiTuTe Of THe uNiVeRSiTy Of CHiCAGO oi.uchicago.edu iv Library of Congress Control Number: 2008926243 iSBN-10: 1-885923-57-0 iSBN-13: 978-1-885923-57-8 iSSN: 0069-3367 The Oriental Institute, Chicago ©2008 by The university of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2008. Printed in the united States of America. ORiental iNSTiTuTe PuBLicatiONS, VOLuMe 135 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. urban with the assistance of Katie L. Johnson Series Editors’ Acknowledgments The assistance of Sabahat Adil, Melissa Bilal, and Scott Branting is acknowledged in the production of this volume. Spine Illustration fragment of a Griffin’s Head (Cat. No. 3.6) Printed by Edwards Brothers, Ann Arbor, Michigan The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for information Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSi Z39.48-1984. oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS LiST Of ABBReViatiONS ............................................................................................................................ -

Sculpture Northwest

Sculpture NorthWestQuarterly January - February - March 2010 ssociation A Inside: Artist Spotlight Michael Gardner Candyce Garrett culptors culptors Jim Heltsley S The German Sculptor Ben Siebenrock Cloudstone tone tone Revealed At Last! S The Lost Trade Of Stone Cutting By Joe Conrad Ben Siebenrock, ‘Hertz’ (Heart), Granite, 6’ high ‘Hertz’ 6’ Granite, (Heart), Siebenrock, Ben est est Summer River W Walks On The Pilchuck Abiquiu Workshops orth N Sculpture NorthWest Quarterly is published every three months by NWSSA, NorthWest Stone In This Issue Sculptors Association, a Washington State Non-Profit Professional Letter From The President ... 3 Organization. Letter From The Editors ... 3 CONTACT P.O. Box 27364 • Seattle, WA 98165-1864 Trivia Question - Answer ... 3, 15 FAX: (206) 523-9280 Website: www.nwssa.org General e-mail: [email protected] NWSSA OFFICERS Gerda Lattey, President, (250) 538-8686 Leon White, Vice President, (206) 390-3145 Petra Brambrink, Treasurer, (503) 975-8690 Lane Tompkins, Secretary, (360) 320-8597 Artist Spotlight: Jim Heltsley, Mike Gardner, Candyce NWSSA BOARD Bill Brayman, (503) 440-0062 Garrett ... 4 Carole Turner, (503) 705-0619 Elaine Mac Kay, (541) 298-1012 PRODUCTION STAFF Penelope Crittenden, Co-editor, (360) 221-2117 Lane Tompkins, Co-editor, (360) 320-8597 DESIGNER Adele Eustis The German Sculptor, Ben Siebenrock ... 6 PUBLISHER Nannette Davis of PrintCore, (425) 485-5570 The Lost Trade Of Stone Cutting ... 8 WEBMASTER Carl Nelson [email protected] 425-252-6812 Cloustone Revealed At Last ... 10 Membership........................................$60/yr. Subscription........................................$30/yr. Please Note: Only full memberships at $60/yr. The Abiquiu Workshops ... 12 include voting privileges and discounted member rates at symposia and workshops.