Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HELFORD Voluntary Marine Conservation Area Newsletter No

HELFORD Voluntary Marine Conservation Area Newsletter No. 36 Spring 2008 Visitors to Constantine Choughs © RSPB In little more than 10 years Little Egrets have become well-established, with hundreds of nesting pairs nationwide. The Choughs will take a little longer, but have already raised 32 young on the Lizard peninsula in the first six years – a success rate none of us would have dared to expect. So, for our next trick…. the Cattle Egret? Since November there has been an unprecedented Little egret © D Chapman influx to our shores of these small, warm-weather herons. Once upon a time – a year or two ago, say! – Are we heading for a happy hat-trick of rarities in this the chance of seeing even a single Cattle Egret would corner of Cornwall – a third breeding bird success fetch out every battalion of the Twitchers’ Army. But story? now…. with more than 30 of these beautiful birds in Cornwall quietly feeding all the way from Bude In the last few years we have seen the arrival in or to Buryan, the Cattle Egret-shaped future must look near the Helford of Little Egrets, first to feed and promising. shelter and now to nest; and the re-arrival after more than 50 years’ absence of the county’s totemic Cattle Egrets are easy to differentiate from those Little Chough. Egrets already familiar along our muddy foreshores: Aim: To safeguard the marine life of the Helford River by any appropriate means within its status as a Voluntary Marine Conservation Area, to increase the diversity of its intertidal community and raise awareness of its marine interest and importance. -

Walks Inland

Round Walks Inland Tregoss Crossing, Belowda Beacon and Castle-an-Dinas 6.30 miles Page 1 **************************************************************************************** Start from the small car park on the old A30 near Tregoss railway level crossing at 96074/60981. Tregoss Crossing Car Park to Belowda – 0.85 miles Set off slightly N of E on the path alongside the old A30. After 135 yards go R and L on a properly made path, slightly N of E, through a horse stile and continue with hedge and old A30 to your L and scrub and the Newquay to Par railway to your R. At 580 yards, at 96592/61034, with a kissing gate to a path to Tregoss to your R, go L across a small wooden bridge over a stream. Cross the old A30 with care to a Public Footpath sign and 4 steps down to a fairly high wooden stile (beware barbed wire) to marshy moorland. An obvious (most of the way) path crosses this stretch of marshy moorland, initially overall roughly NNE, then overall roughly N, dabs of yellow paint generally marking the way. This path is classified by Cornwall Council as ‘silver’ but actually merits a rating of less then bronze. At 625 yards cross a tiny clapper bridge, then boggy tussocks for a short way. At 655 yards you are veering slightly away from a barbed wire fence to your R. At 695 yards cross another small clapper with an iron railing to more boggy ground. Continue to a low granite stile leading to wooden duck-boards to some slightly firmer ground. -

Copyrighted Material

176 Exchange (Penzance), Rail Ale Trail, 114 43, 49 Seven Stones pub (St Index Falmouth Art Gallery, Martin’s), 168 Index 101–102 Skinner’s Brewery A Foundry Gallery (Truro), 138 Abbey Gardens (Tresco), 167 (St Ives), 48 Barton Farm Museum Accommodations, 7, 167 Gallery Tresco (New (Lostwithiel), 149 in Bodmin, 95 Gimsby), 167 Beaches, 66–71, 159, 160, on Bryher, 168 Goldfish (Penzance), 49 164, 166, 167 in Bude, 98–99 Great Atlantic Gallery Beacon Farm, 81 in Falmouth, 102, 103 (St Just), 45 Beady Pool (St Agnes), 168 in Fowey, 106, 107 Hayle Gallery, 48 Bedruthan Steps, 15, 122 helpful websites, 25 Leach Pottery, 47, 49 Betjeman, Sir John, 77, 109, in Launceston, 110–111 Little Picture Gallery 118, 147 in Looe, 115 (Mousehole), 43 Bicycling, 74–75 in Lostwithiel, 119 Market House Gallery Camel Trail, 3, 15, 74, in Newquay, 122–123 (Marazion), 48 84–85, 93, 94, 126 in Padstow, 126 Newlyn Art Gallery, Cardinham Woods in Penzance, 130–131 43, 49 (Bodmin), 94 in St Ives, 135–136 Out of the Blue (Maraz- Clay Trails, 75 self-catering, 25 ion), 48 Coast-to-Coast Trail, in Truro, 139–140 Over the Moon Gallery 86–87, 138 Active-8 (Liskeard), 90 (St Just), 45 Cornish Way, 75 Airports, 165, 173 Pendeen Pottery & Gal- Mineral Tramways Amusement parks, 36–37 lery (Pendeen), 46 Coast-to-Coast, 74 Ancient Cornwall, 50–55 Penlee House Gallery & National Cycle Route, 75 Animal parks and Museum (Penzance), rentals, 75, 85, 87, sanctuaries 11, 43, 49, 129 165, 173 Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Round House & Capstan tours, 84–87 113 Gallery (Sennen Cove, Birding, -

Dog Fouling at Cadgwith Shared Lives Caring Friends of Kennack

Inside This Month All our regular features, plus: Dog Fouling at Cadgwith Shared Lives Caring Friends of Kennack One copy free to each household, 90p business and holiday let in the Parish 2 DATES FOR THE DIARY Alternate Weds Recycling - 3,17 February Every 4 weeks Mobile Library: Glebe Place 10.25 am -10.45 am, 10 February, 9 March 1st Sunday Friends of Kennack Beach Clean. Meet at car park. 10am 7 February 2nd Monday 7.30pm Parish Council meeting, Methodist Chapel, 8 February 3rd Tuesday 12.15pm Soup, Pasty, Pudding, Methodist Chapel, 16 February 4th Tuesday 7.30pm Quiz in the Village Hall, 23 February Mon & Thurs 7.00pm Short Mat Bowling, Village Hall Every Tues (except 3rd Tues) 10am Coffee morning, Methodist Chapel Every Weds Rainbows, Brownies & Guides. Contact Joy Prince Tel: 01326 290280 Every Thurs 9.00am - 11.45am Market and refreshments - Village Hall Every Thurs Yoga at the Village Hall - 5.30 - 6.30 pm FEBRUARY (SEE “WHAT’S ON” FOR MORE DETAILS) 4 February Meeting about the Play Area, 7pm in the Chapel 13 - 21 February Spring Half-term, Grade Ruan Primary school 17 - 20 February “A Bad Day at Black Frog Creek” in the Village Hall, 7.30pm 24 February Cadgwith Book Club, 8pm Cadgwith Cove Inn ADVANCE DATES 19 March Spring Flower Show, 2.30pm Village Hall 23 March Cadgwith Book Club, 8pm Cadgwith Cove Inn 28 - 30 May May Festival, Recreation Ground 20 July Beach BBQ, organized by the Gig Club 27 July Beach BBQ, organized by the Lights Committee 3 August Beach BBQ, organized by the Rec Committee 6 August Vintage Rally Night Before Party 7 August Grade Ruan Vintage Rally 10 August Beach BBQ, organized by the Gig Club 17 August Beach BBQ, organized by the Lights Committee 24 August Beach BBQ, organized by the Rec Committee Front Cover: Swimmers, all dressed up and ready for the plunge on Christmas Day. -

Community Network Member Electoral Division Organisation / Project Grant Description Grant Amount Year St Blazey, Fowey & Lo

Community Electoral Organisation / Grant Network Member Division Project Grant Description Amount Year St Blazey, Squires Field Fowey & Fowey & Community Purchase of Lostwithiel Virr A Tywardreath Centre Storage Shed £500.00 2017-18 St Blazey, Fowey & Par & St Blazey Surf Life Saving ECO Surf life Lostwithiel Rowse J Gate Great Britain saving Champs £50.00 2017-18 St Blazey, Fowey & Fowey & Fowey Town Disabled Swing for Lostwithiel Virr A Tywardreath Council Squires Field £500.00 2017-18 St Blazey, Materials for Fowey & Fowey & Fowey Town painting of Lostwithiel Virr A Tywardreath Forum benches £257.80 2017-18 St Blazey, Contribution to Fowey & St Blazey Lantern Making Lostwithiel Giles P St Blazey Reclaimed Workshops £150.00 2017-18 St Blazey, Contribution to Fowey & Par & St Blazey St Blazey Lantern Making Lostwithiel Rowse J Gate Reclaimed Workshops £100.00 2017-18 St Blazey, Drama Express Fowey & Pantomime 2018 - Lostwithiel Giles P St Blazey Drama Express Venue Hire £200.00 2017-18 St Blazey, Fowey & Kernow Youth Lostwithiel Giles P St Blazey CIC Ice Skating Trip £150.00 2017-18 St Blazey, Fowey & PL24 Community Christmas Cheer Lostwithiel Giles P St Blazey Association 2017 £200.00 2017-18 St Blazey, Ingredients for Fowey & Keep Cornwall meals for those in Lostwithiel Giles P St Blazey Fed food poverty £200.00 2017-18 St Blazey, Fowey & Par & St Blazey Friends of Par Volunteer Group - Lostwithiel Rowse J Gate Beach Storage £300.00 2017-18 St Blazey, Purchase of Fowey & Par & St Blazey PL24 Community outdoor seating for Lostwithiel -

Helston and South Kerrier Cormac Community Programme

Cormac Community Programme Helston and South Kerrier Community Network Area ........ Please direct any enquiries to [email protected] ...... Project Name Anticipated Anticipated Anticipated Worktype Location Electoral Division TM Type - Primary Duration Start Finish WEST WEST-Helston & South Kerrier Contracting Breage Burial Ground_Helston_Boundary Wall Repairs 5 d Aug 2021 Aug 2021 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) Helston Porthleven Breage & Germoe Some Carriageway Incursion (SLGI) Highways and Construction Works B3297 Redruth to Helston - Safety Improvements 40 d Jun 2021 Aug 2021 Signs Crowan Crowan Sithney & Wendron 2WTL (2 Way Signals) Mullion 4 Phase 2 - Ghost Hill, Mullion, TR12 7EY - Surfacing & Drainage 22 d Jul 2021 Aug 2021 Public Rights of Way (PROW) Mullion Ludgvan Madron Gulval & Heamoor Not Required Route 105 R7 Mawgan - Rural Maintenance 8 d Aug 2021 Aug 2021 Cyclic Maintenance Mawgan Helston South & Meneage Not Required Route 105 R3 Coverack - Rural Maintenance 8 d Aug 2021 Aug 2021 Cyclic Maintenance Coverack Mullion & St Keverne Not Required Balwest Ditches - Tresowes Hill, Ashton - Ditching 2 d Aug 2021 Aug 2021 Verge Maintenance Ashton Porthleven Breage & Germoe Priority Working White Cross signs, Cury - Signs 1 d Aug 2021 Aug 2021 Signs Cury Mullion & St Keverne Give and Take Rosuick & Maindale, St Keverne - Catle Grid cleaning 1 d Aug 2021 Aug 2021 Drainage Maintenance St Keverne Mullion & St Keverne Not Required Carey Park, Helston revisit - Vegetation removal 1 d Aug 2021 Aug 2021 Vegetation Works -

Bat Trail-11-Tamar

bat trail‐11 3 Tamar Valley Drakewalls Walk 2 4 Tamar Valley 1 Centre T P 6 9 8 5 7 Key Trail Cemetery Road Alternative Route Bus Stop B Car Park Toilets T Refreshment View Point Photo: Tamar Valley AONB The steeply sloping and heavily wooded landscape of the Tamar way around the landscape. Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) forms the boundary between Devon and Cornwall. Mining history is key to Take a stroll around the Drakewalls Mine site and find out more the story of the valley and the remains around the former Devon about the habitats and landscapes that are great for greater Directions Great Consols mine are important for the local greater horseshoe horseshoe bats and other bat species in the valley. bat population. Start at the Tamar Valley Centre and head towards the rides are important feeding areas and navigational routes for The old mine at Devon Great Consols supports a key maternity old buildings in the grounds. These are the remains of the bats. They tend to be sheltered areas where insects roost for greater horseshoe bats. Wooded valleys, river corridors, networks of hedgerows and cattle-grazed pastures that surround former Drakewalls Mine. The nooks and crannies of the old congregate, creating the perfect bat buffet! Tree branches are the roost are great for feeding bats and help them to find their buildings, pits and adits form places for bats to rest and roost. also important for greater horseshoes to perch on whilst they They are also make good habitats for insects, which the bats eat their prey. -

Isles of Scilly

Isles of Scilly Naturetrek Tour Report 14 - 21 September 2019 Porthcressa and the Garrison Red Squirrel Grey Seals Birdwatching on Peninnis Head Report & Images by Andrew Cleave Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Isles of Scilly Tour participants: Andrew Cleave (leader) plus 12 Naturetrek clients Summary Our early-autumn week on the Isles of Scilly was timed to coincide with the bird migration which is easily observed on the islands. Our crossings to and from Scilly on Scillonian III enabled us to see seabirds in their natural habitat, and the many boat trips we took during the week gave us close views of plenty of the resident and migrant birds which were feeding and sheltering closer to shore. We had long walks on all of the inhabited islands and as well as birds, managed to see some marine mammals, many rare plants and some interesting intertidal marine life. Informative evening lectures by resident experts were well received and we also sampled lovely food in many of the pubs and cafés on the islands. Our waterfront accommodation in Schooners Hotel was very comfortable and ideally placed for access to the harbour and Hugh Town. Day 1 Saturday 14th September We began our trip in Penzance harbour where we boarded Scillonian III for the crossing to Scilly. Conditions were fine for the crossing and those of us up on deck had good views of seabirds, including Gannets, Fulmars and winter-plumage auks as we followed the Cornish coast and then headed out into the Atlantic. -

What Grows Together, Goes Together

WHAT GROWS TOGETHER, GOES TOGETHER. BAR & LOUNGE MENU CORNWALL’S SANDWICHES TREGOTHNAN CORNISH FINEST Aged Davidstow Cheddar with LOOSE manor piccalilli 7.00 CLASSIC LEAF TEA BBC bacon, brie and cheddar open The Woodyard, Tregothnan, Tresillian, toasted croissant 7.00 AFTERNOON TEA Truro, Cornwall We love food and drink, who doesn’t served between 15:00 – 18:00 these days. Phillip Warren Rare Beef, Earl Grey leaf & blue cheese dressing 8.00 Classic For us it’s all about authentic local Manor smoked salmon, chive cream cheese It goes without saying that you cannot Chamomile produce served in interesting or traditional & pickled cucumber 8.00 come to Cornwall without indulging in a Green Peppermint ways and packed with flavour. From our Cornish afternoon tea. From delicately Red Berry nature-inspired modern approach in handmade finger sandwiches to innovative Pot of Tea 3.00 Rastella for dinner through to our locally LIGHTS flavour combinations, afternoon tea at grass-reared beef burgers smothered Merchants Manor is not to be missed. with our manor-made barbecue sauce, Market vegetable soup 6.00 everything is put together with thought OLFACTORY COFFEE Falmouth Caesar salad, sourdough croute, and pure enjoyment in mind. parmesan shavings 8.00 SELECTION OF AFTERNOON Specialty Coffee Roasters, Add mackerel 4.00 Add steak 6.00 FINGER SANDWICHES Old Brewery Yard, Penryn, Cornwall We pay close attention to provenance, Americano 2.90 locality, seasonality and sustainability, so Philip Warrens Steak Burger, cheddar, Manor smoked salmon Cafetiere 2.90 you don’t have to. This means you will find handcut chips 14.50 Espresso 2.90 a vast array of food and drink that ‘ticks’ Egg mayonnaise on home-made Cappuccino 3.00 all the boxes and not because we have to Fish and chips, sourdough beer batter, bridge rolls Latte 3.00 but because we should all want to. -

Worth a Conquest: the Roman Invasion of Britannia

Worth a Conquest: The Roman Invasion of Britannia Skara Brae, An Ancient Village - Island of the White Cliffs - A Celtic Land Shrouded in Mystery - Caesar’s Pearls - Leap, My Fellow Soldiers! - Caesar Strikes Back - A Terrifying Elephant! - Crazy Caligula’s Cockle Shells - Claudius Turns His Eye on Britain - Claudius Conquers, and a King Turns Christian - Boudicca’s Wild Uprising - Roman Britain - Birthdays, Complaints, and Warm Clothes – Britain’s First Martyrs Skara Brae- An Ancient Village http://www.orkneyjar.com/history/skarabrae/ Begin your discovery of ancient Britain by following the link above, and uncover the remains of Skara Brae. Explore all the pages listed in the “Section Contents” menu on the right, and particularly have a look at the pictures. Charles Dickens: Island of the White Cliffs From the History of England In the old days, a long, long while ago, before Our Saviour was born on earth(…) these Islands were in the same place, and the stormy sea roared round them, just as it roars now. But the sea was not alive, then, with great ships and brave sailors, sailing to and from all parts of the world(…)The Islands lay solitary, in the great expanse of water. The foaming waves dashed against their cliffs, and the bleak winds blew over their forests; but the winds and waves brought no adventurers to land upon the Islands, and the savage Islanders knew nothing of the rest of the world, and the rest of the world knew nothing of them. It is supposed that the Phœnicians, who were an ancient people, famous for carrying on trade, came in ships to these Islands, and found that they produced tin and lead; (…) The most celebrated tin mines in Cornwall are, still, close to the sea. -

North Cornwall

NORTH CORNWALL TRAILS with GEOLOGICAL INTEREST along the coast from BUDE to BOSCASTLE Ref. OS Explorer Map 111 Bude, Boscastle & Tintagel SETTING THE SCENE. The geological origins of the area date back to the Upper Devonian (377-360 Ma) in the south and the Carboniferous Period (360-290Ma) in the north of the region. The area then lay just north of the equator and was beneath the Rheic Ocean, the seabed consisted of sands and silts deposited by great river delta's flowing from the north. Around 290Ma, during the Variscan Orogeny, the seabed was squeezed upwards forming high mountains, which were subsequently eroded away. Again, at around 145Ma the area was once more dominated by the sea. Then 2Ma the Ice Age impacted on the region with a tundra climate and permafrost producing glacial head formed by the freezing and thawing of the land. This was followed by a great thaw and erosion by the elements to form the landscape we see today, complete with evidence of stages through which it evolved. The sedimentary Devonian and Carboniferous rocks have been intensely deformed and folded into complex structures clearly visible in the coastal sections from Bude to Boscastle. Selected Geological Features can be seen at the following locations:- TRAIL 1. 1. BUDE SYNCLINE and ANTICLINE SS 202065 2. BUDE WHALE ROCK SS 199065 3. BUDE TURBIDITES SS 203069 TRAIL 2. 4. MILLOOK HAVEN SS 186006 TRAIL 3. 5. CRACKINGTON HAVEN SX 142969 TRAIL 4. 6. BOSCASTLE SX 100913 7. LADIES WINDOW SX 080906 TRAIL 1. 1. BUDE SYNCLINE and ANTICLINE SS 202065 2. -

Name of Deceased (Surname First)

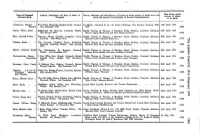

Date before which Name of Deceased Address, description and date of death of Names, addresses and descriptions of Persons to whom notices of claims are to be notices of claims (Surname first) Deceased given and names, in parentheses, of Personal Representatives to be given LITCHFIELD, Harold Pine Trees, Watcombe Heights Road, Torquay. Lee-Barber, Goodrich & Co., St. Johns Chambers, The Terrace, Torquay, TQ1 14th April 1974 Edward. 13th December 1973. IBP. (284) CHINN, Thirza Johns ... Ridgewood, St. Keverne, Cornwall, Widow. Randle Thomas & Thomas, 2 Wendron Street, Helston, Cornwall, Solicitors. 20th April 1974 13th January 1974. (Doctor Agnes Blackwood and Peter Hayes London.) (296) BRAY, Almond Foster ... Chycoose House, Coombe, Cusgarne, Truro, Randle Thomas & Thomas, 2 Wendron Street, Helston, Cornwall, Solicitors. 20th April 1974 Cornwall. 10th March 1973. (Emerald Leone Mitchell Burrows.) (297) THOMAS, Sarah The Caravan, Lindford House, Penhallick, Randle Thomas & Thomas, 2 Wendron Street, Helston, Cornwall, Solicitors. 20th April 1974 Coverack, Cornwall, Widow. 26th January (Richard John Harry and Alan Archibald Thorne.) (298) 1974. HODGE, Winifred Emily The Churchtown, St. Keverne, Cornwall, Randle Thomas & Thomas, 2 Wendron Street, Helston, Cornwall, Solicitors. 20th April 1974 Widow. 31st December 1973. (Joseph Brian Roskilly and Alan Archibald Thorne.) (299) GOLDSWORTHY, Henry 4 Post Office Row, Gweek, Cornwall, Retired Randle Thomas & Thomas, 2 Wcndron Street, Helston, Cornwall, Solicitors. 20th April 1974 Courtenay. Cornish Stone Hedger. 24th December (Henry Owen Goldsworthy and Terence James Thomas.) (300) 1973. EDWARDS, Percy Pearce 12 Osborne Pare, Helston, Cornwall, Retired Randle Thomas & Thomas, 2 Wendron Street, Helston, Cornwall, Solicitors. 20th April 1974 Mining Engineer. 20th December 1973. (Lloyds Bank Limited, Executor and Trustee Department.) (301) W THOMAS, Adelaide Wheal Vor, Breage, Helston, Cornwall, Spinster.