The Rhetoric and Reality of Learning to Be a Sage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Analects of Confucius

© 2003, 2012, 2015 Robert Eno This online translation is made freely available for use in not for profit educational settings and for personal use. For other purposes, apart from fair use, copyright is not waived. Open access to this translation is provided, without charge, at http://www.indiana.edu/~p374/Analects_of_Confucius_(Eno-2015).pdf Also available as open access translations of the Four Books Mencius: An Online Teaching Translation http://www.indiana.edu/~p374/Mengzi.pdf Mencius: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://www.indiana.edu/~p374/Mencius (Eno-2016).pdf The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: An Online Teaching Translation http://www.indiana.edu/~p374/Daxue-Zhongyong.pdf The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://www.indiana.edu/~p374/Daxue-Zhongyong_(Eno-2016).pdf The Analects of Confucius Introduction The Analects of Confucius is an anthology of brief passages that present the words of Confucius and his disciples, describe Confucius as a man, and recount some of the events of his life. The book may have begun as a collection by Confucius’s immediate disciples soon after their Master’s death in 479 BCE. In traditional China, it was believed that its contents were quickly assembled at that time, and that it was an accurate record; the Eng- lish title, which means “brief sayings of Confucius,” reflects this idea of the text. (The Chinese title, Lunyu 論語, means “collated conversations.”) Modern scholars generally see the text as having been brought together over the course of two to three centuries, and believe little if any of it can be viewed as a reliable record of Confucius’s own words, or even of his individual views. -

The Analects of Confucius

The analecTs of confucius An Online Teaching Translation 2015 (Version 2.21) R. Eno © 2003, 2012, 2015 Robert Eno This online translation is made freely available for use in not for profit educational settings and for personal use. For other purposes, apart from fair use, copyright is not waived. Open access to this translation is provided, without charge, at http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23420 Also available as open access translations of the Four Books Mencius: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23421 Mencius: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23423 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23422 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23424 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i MAPS x BOOK I 1 BOOK II 5 BOOK III 9 BOOK IV 14 BOOK V 18 BOOK VI 24 BOOK VII 30 BOOK VIII 36 BOOK IX 40 BOOK X 46 BOOK XI 52 BOOK XII 59 BOOK XIII 66 BOOK XIV 73 BOOK XV 82 BOOK XVI 89 BOOK XVII 94 BOOK XVIII 100 BOOK XIX 104 BOOK XX 109 Appendix 1: Major Disciples 112 Appendix 2: Glossary 116 Appendix 3: Analysis of Book VIII 122 Appendix 4: Manuscript Evidence 131 About the title page The title page illustration reproduces a leaf from a medieval hand copy of the Analects, dated 890 CE, recovered from an archaeological dig at Dunhuang, in the Western desert regions of China. The manuscript has been determined to be a school boy’s hand copy, complete with errors, and it reproduces not only the text (which appears in large characters), but also an early commentary (small, double-column characters). -

Zhuangzi: the Inner Chapters 莊子。內篇

Zhuangzi: The Inner Chapters 莊子。內篇 Translated by Version 1.1 Robert Eno 2019 © 2010, 2016, 2019 Robert Eno This online translation is made freely available for use in not-for-profit educational settings and for personal use. For other purposes, apart from fair use, copyright is not waived. Open access to this translation of Zhuangzi: The Inner Chapters is provided, without charge, at: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23427 Also available as open access translations: Dao de jing http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23426 The Analects of Confucius: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23420 Mencius: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23421 Mencius: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23423 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23422 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23424 Liji [Book of Rites], Chapters 3-4: “Tan Gong”: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23425 Note for readers This translation was originally prepared for use by students in a general course on early Chinese thought. My initial intention was simply to provide my own students with a version that conveyed the way I thought the text was probably best understood. Of course, I was also happy to make a reasonably responsible rendering of the text available for my students at no cost. I later posted the text online with this latter goal in mind for teachers who wished to select portions of the text for classroom discussion without requiring students to make additional costly purchases or dealing with troublesome issues of copyright in assembling extracts. -

Discourses and Practices of Confucian Friendship in 16Th-Century Korea Isabelle Sancho

Discourses and Practices of Confucian Friendship in 16th-Century Korea Isabelle Sancho To cite this version: Isabelle Sancho. Discourses and Practices of Confucian Friendship in 16th-Century Korea. Licence. European Program for the Exchange of Lecturers (EPEL)- The Association for Korean Studies in Europe, Bucharest, Romania. 2014. hal-02905241 HAL Id: hal-02905241 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02905241 Submitted on 24 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Friday May 30, 2014 University of Bucharest - EPEL talk Isabelle SANCHO CNRS-EHESS Paris “Discourses and Practices of Confucian Friendship in 16th-Century Korea” The original Confucian school might be described as starting with a group of disciples and friends gathering together around the central figure of a master: Confucius, Master Kong. The man Confucius, as he has been staged in the text of the Analects, is always surrounded by a few key figures with distinct personalities, social backgrounds, and trajectories: the practical and straight-talker Zilu with military training, the gifted and politically skilled Zigong coming from a wealthy family, the youngest and favorite disciple Yan Hui from humble origins whose premature death left the Master inconsolable, Zengzi keen on transmitting the supposed true teachings of Confucius and to whom is attributed the Book of Filial Piety, etc. -

The Teachings of Confucius: a Basis and Justification for Alternative Non-Military Civilian Service

THE TEACHINGS OF CONFUCIUS: A BASIS AND JUSTIFICATION FOR ALTERNATIVE NON-MILITARY CIVILIAN SERVICE Carolyn R. Wah* Over the centuries the teachings of Confucius have been quoted and misquoted to support a wide variety of opinions and social programs ranging from the suppression and sale of women to the concerted suicide of government ministers discontented with the incoming dynasty. Confucius’s critics have asserted that his teachings encourage passivity and adherence to rites with repression of individuality and independent thinking.1 The case is not that simple. A careful review of Confucius’s expressions as preserved by Mencius, his student, and the expressions of those who have studied his teachings, suggests that Confucius might have found many of the expressions and opinions attributed to him to be objectionable and inconsistent with his stated opinions. In part, this misunderstanding of Confucius and his position on individuality, and the individual’s right to take a stand in opposition to legitimate authority, results from a distortion of two Confucian principles; namely, the principle of legitimacy of virtue, suggesting that the most virtuous man should rule, and the principle of using the past to teach the present.2 Certainly, even casual study reveals that Confucius sought political stability, but he did not discourage individuality or independent *She is associate general counsel for Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania. She received her J.D. from Rutgers University Law School and B.A. from The State University of New York at Oswego. She has recently received her M.A. in liberal studies with an emphasis on Chinese studies from The State University of New York—Empire State College. -

Mencius on Becoming Human a Dissertation Submitted To

UNIVERSITY OF HAWNI LIBRARY MENCIUS ON BECOMING HUMAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN PHILOSOPHY DECEMBER 2002 By James P. Behuniak Dissertation Committee: Roger Ames, Chairperson Eliot Deutsch James Tiles Edward Davis Steve Odin Joseph Grange 11 ©2002 by James Behuniak, Jr. iii For my Family. IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With support from the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Hawai'i, the Harvard-Yenching Institute at Harvard University, and the Office of International Relations at Peking University, much of this work was completed as a Visiting Research Scholar at Peking Univeristy over the academic year 2001-2002. Peking University was an ideal place to work and I am very grateful for the support of these institutions. I thank Roger Ames for several years of instruction, encouragement, generosity, and friendship, as well as for many hours of conversation. I also thank the Ames family, Roger, Bonney, and Austin, for their hospitality in Beijing. I thank Geir Sigurdsson for being the best friend that a dissertation writer could ever hope for. Geir was also in Beijing and read and commented on the manuscript. I thank my committee members for comments and recommendations submitted over the course of this work. lowe a lot to Jim Tiles for prompting me to think through the subtler components of my argument. I take full responsibility for any remaining weaknesses that carry over into this draft. I thank my additional member, Joseph Grange, who has been a mentor and friend for many years. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, AUGUST 1966-JANUARY 1967 Zehao Zhou, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor James Gao, Department of History This dissertation examines the attacks on the Three Kong Sites (Confucius Temple, Confucius Mansion, Confucius Cemetery) in Confucius’s birthplace Qufu, Shandong Province at the start of the Cultural Revolution. During the height of the campaign against the Four Olds in August 1966, Qufu’s local Red Guards attempted to raid the Three Kong Sites but failed. In November 1966, Beijing Red Guards came to Qufu and succeeded in attacking the Three Kong Sites and leveling Confucius’s tomb. In January 1967, Qufu peasants thoroughly plundered the Confucius Cemetery for buried treasures. This case study takes into consideration all related participants and circumstances and explores the complicated events that interwove dictatorship with anarchy, physical violence with ideological abuse, party conspiracy with mass mobilization, cultural destruction with revolutionary indo ctrination, ideological vandalism with acquisitive vandalism, and state violence with popular violence. This study argues that the violence against the Three Kong Sites was not a typical episode of the campaign against the Four Olds with outside Red Guards as the principal actors but a complex process involving multiple players, intraparty strife, Red Guard factionalism, bureaucratic plight, peasant opportunism, social ecology, and ever- evolving state-society relations. This study also maintains that Qufu locals’ initial protection of the Three Kong Sites and resistance to the Red Guards were driven more by their bureaucratic obligations and self-interest rather than by their pride in their cultural heritage. -

China's Nationalism and Its Quest for Soft Power Through Cinema

Doctoral Thesis for PhD in International Studies China’s Nationalism and Its Quest for Soft Power through Cinema Frances (Xiao-Feng) Guo University of Technology, Sydney 2013 Acknowledgement To begin, I wish to express my great appreciation to my PhD supervisor Associate Professor Yingjie Guo. Yingjie has been instrumental in helping me shape the theoretical framework, sharpen the focus, and improve the structure and the flow of the thesis. He has spent a considerable amount of time reading many drafts and providing insightful comments. I wish to thank him for his confidence in this project, and for his invaluable support, guidance, and patience throughout my PhD program. I also wish to thank Professor Wanning Sun and Professor Louise Edwards for their valued support and advice. I am grateful for the Australian Postgraduate Award that I received via UTS over the three-and-half years during my candidature. The scholarship has afforded me the opportunity to take the time to fully concentrate on my PhD study. I am indebted to Yingjie Guo and Louise Edwards for their help with my scholarship application. I should also thank UTS China Research Centre, the Research Office of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at UTS, and UTS Graduate Research School for their financial support for my fieldwork in China and the opportunities to present papers at national and international conferences during my doctoral candidature. Finally, my gratitude goes to my family, in particular my parents. Their unconditional love and their respect for education have inspired me to embark on this challenging and fulfilling journey. -

Where Did All the Filial Sons Go?

CHAPTER 1 Where Did All the Filial Sons Go? In the year 73 BCE, the most powerful man in the Han empire, the General- in-Chief (da jiangjun 大將軍) Huo Guang 霍光 (d. 68 BCE), charged Liu He 劉賀 (ca. 92–59 BCE), the Imperial Heir Apparent, with ritual misconduct. The General called for Liu’s removal from power as the result of a scandal involving sex, alcohol, and a man ostensibly in mourning. In a memorial to the empress dowager, Huo enumerated the crimes of the eighteen-year-old Liu. While in mourning for his imperial predecessor, the young man indulged in such pastimes as visiting zoos and bringing entertainers into the palace, when music and dance were not only in poor taste, but also strictly forbid- den to mourners. He used public money for making gifts of concubines to his friends and imprisoned officials who tried to admonish him.1 Worse still, Liu ate meat, drank spirits, and engaged in sexual activity (all forbidden to mourners). In fact, while traveling to the capital, he ordered his subordinates to seize women on the road and load them into screened carriages. Upon his arrival in the capital, the debauchery continued, as Liu and his followers took liberties with women from the dead emperor’s harem. Acts such as these led Huo to conclude, not unreasonably, that the young man, though he wore the garments of deepest mourning, was “without sorrow or grief in his heart.”2 Such a lack of filial piety, Huo reminded the empress dowager, was the grav- est of crimes, and thus called for severe punishment and removal from power.3 Huo’s arguments met with imperial favor: not long afterwards, Liu’s riotous followers were executed, and he was duly removed as heir apparent and sent back to the provinces. -

<I>Daxue and Zhongyong: Bilingual Edition</I> Translator by Ian

Book Reviews Ian Johnston and Wang Ping, translators and annotators. Daxue and Zhongyong: Bilingual Edition. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2012. Pp. 567. $80 (hardcover). ISBN 978-962-996-445-0. This is a must-have book for anyone with a serious interest in the two seminal Confucian texts Daxue 大學 and Zhongyong 中庸, usually translated as the Great Learning and the Doctrine of the Mean. It is much more than an anno- tated translation with introduction. First of all, it includes two versions of each text. The first is the version found in theLiji 禮記 (Record of Ritual), where the Daxue was chapter 42 and the Zhongyong was chapter 31. This is accompanied by the most authoritative commentaries of the Han and Tang dynasties, by Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (127–200) and Kong Yingda 孔穎達 (574–648), as found in the Shisanjing zhushu 十三經注疏 (The Thirteen Classics with Notes and Commentary), edited by Ruan Yuan 阮元 (1764–1849). Zheng Xuan’s notes are mostly philological and quite brief, while Kong Yingda’s comments are more philosophical and much longer. The second is the text as found in the Sishu zhangju jizhu 四書章句集注 (The Four Books in Chapters and Sentences) by Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200), along with his commentary. Both the texts themselves and the commentaries are given in Chinese and English on facing pages. The notes on Chinese pronunciation are given in the Chinese but are omitted, with ellipses, in the English. In addition, there is a General Introduction (15 pages); an Introduction to each text (22 and 29 pages, respectively); three appendices: “The Origin of the Liji” (3 pages), “Commentaries and Translations” (21 pages), and “Terminology” (28 pages); a classified bibliography; an index of names; and a general index. -

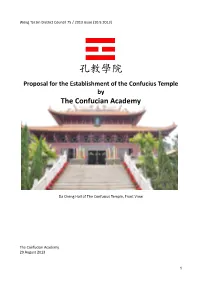

Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by the Confucian Academy

Wong Tai Sin District Council 75 / 2013 issue (10.9.2013) 孔教學院 Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by The Confucian Academy Da Cheng Hall of The Confucius Temple, Front View The Confucian Academy 29 August 2013 1 Content 1. Objectives ……………………………………………………….………………..……….…………… P.3 2. An Introduction to Confucianism …………………………………..…………….………… P.3 3. Confucius, the Confucius Temple and the Confucian Academy ………….….… P.4 4. Ideology of the Confucius Temple ………………………………..…………………….…… P.5 5. Social Values in the Construction of the Confucius Temple …………..… P.7 – P.9 6. Religious Significance of the Confucius Temple…………………..……….… P.9 – P.12 7. Cultural Significance of the Confucius Temple…………………………..……P.12- P.18 8. Site Selection ………………………………………………………………………………………… P.18 9. Gross Floor Area (GFA) of the Confucius Temple …………………….………………P.18 10. Facilities …………………………………………………………………….……………… P.18 – P.20 11. Construction, Management and Operation ……………….………………. P.20– P.21 12. Design Considerations ………………………………………………………………. P.21 – P.24 13. District Consultation Forums .…………………………………..…………….…………… P.24 14. Alignment with Land Use Development …….. …………………………….………… P.24 15. The Budget ……………………………………………………………………………………………P.24 ※ Wong Tai Sin District and the Confucius Temple …………………………….….... P.25 Document Submission……………………………………………………………………………….. P.26 Appendix 1. Volume Drawing (I) of the Confucius Temple ………………..……….P.27 Appendix 2. Volume Drawing (II) of the Confucius Temple …………….………….P.28 Appendix 3. Design Drawings of the Confucius Temple ……………………P.29 – P.36 2 Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by the Confucian Academy 1. Objectives This document serves as a proposal for the construction of a Confucius Temple in Hong Kong by the Confucian Academy, an overview of the design and architecture of the aforementioned Temple, as well as a way of soliciting the advice and support from the Wong Tai Sin District Council and its District Councillors. -

Sun Tzu the Art Of

SUN TZU’S BILINGUAL CHINESE AND ENGLISH TEXT Art of war_part1.indd i 28/4/16 1:33 pm To my brother Captain Valentine Giles, R. C., in the hope that a work 2400 years old may yet contain lessons worth consideration to the soldier of today, this translation is affectionately dedicated SUN TZU BILINGUAL CHINESE AND ENGLISH TEXT With a new foreword by John Minford Translated by Lionel Giles TUTTLE Publishing Tokyo Rutland, Vermont Singapore ABOUT TUTTLE “Books to Span the East and West” Our core mission at Tuttle Publishing is to create books which bring people together one page at a time. Tuttle was founded in 1832 in the small New England town of Rutland, Vermont (USA). Our fundamental values remain as strong today as they were then—to publish best-in-class books informing the English-speaking world about the countries and peoples of Asia. The world has become a smaller place today and Asia’s economic, cultural and political infl uence has expanded, yet the need for meaning- ful dialogue and information about this diverse region has never been greater. Since 1948, Tuttle has been a leader in publishing books on the cultures, arts, cuisines, lan- guages and literatures of Asia. Our authors and photographers have won numerous awards and Tuttle has published thousands of books on subjects ranging from martial arts to paper crafts. We welcome you to explore the wealth of information available on Asia at www.tuttlepublishing.com. Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Distributed by Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. North America, Latin America & Europe www.tuttlepublishing.com Tuttle Publishing 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon Copyright © 2008 Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.