<I>Daxue and Zhongyong: Bilingual Edition</I> Translator by Ian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Analects of Confucius

The analecTs of confucius An Online Teaching Translation 2015 (Version 2.21) R. Eno © 2003, 2012, 2015 Robert Eno This online translation is made freely available for use in not for profit educational settings and for personal use. For other purposes, apart from fair use, copyright is not waived. Open access to this translation is provided, without charge, at http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23420 Also available as open access translations of the Four Books Mencius: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23421 Mencius: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23423 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23422 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23424 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i MAPS x BOOK I 1 BOOK II 5 BOOK III 9 BOOK IV 14 BOOK V 18 BOOK VI 24 BOOK VII 30 BOOK VIII 36 BOOK IX 40 BOOK X 46 BOOK XI 52 BOOK XII 59 BOOK XIII 66 BOOK XIV 73 BOOK XV 82 BOOK XVI 89 BOOK XVII 94 BOOK XVIII 100 BOOK XIX 104 BOOK XX 109 Appendix 1: Major Disciples 112 Appendix 2: Glossary 116 Appendix 3: Analysis of Book VIII 122 Appendix 4: Manuscript Evidence 131 About the title page The title page illustration reproduces a leaf from a medieval hand copy of the Analects, dated 890 CE, recovered from an archaeological dig at Dunhuang, in the Western desert regions of China. The manuscript has been determined to be a school boy’s hand copy, complete with errors, and it reproduces not only the text (which appears in large characters), but also an early commentary (small, double-column characters). -

Discourses and Practices of Confucian Friendship in 16Th-Century Korea Isabelle Sancho

Discourses and Practices of Confucian Friendship in 16th-Century Korea Isabelle Sancho To cite this version: Isabelle Sancho. Discourses and Practices of Confucian Friendship in 16th-Century Korea. Licence. European Program for the Exchange of Lecturers (EPEL)- The Association for Korean Studies in Europe, Bucharest, Romania. 2014. hal-02905241 HAL Id: hal-02905241 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02905241 Submitted on 24 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Friday May 30, 2014 University of Bucharest - EPEL talk Isabelle SANCHO CNRS-EHESS Paris “Discourses and Practices of Confucian Friendship in 16th-Century Korea” The original Confucian school might be described as starting with a group of disciples and friends gathering together around the central figure of a master: Confucius, Master Kong. The man Confucius, as he has been staged in the text of the Analects, is always surrounded by a few key figures with distinct personalities, social backgrounds, and trajectories: the practical and straight-talker Zilu with military training, the gifted and politically skilled Zigong coming from a wealthy family, the youngest and favorite disciple Yan Hui from humble origins whose premature death left the Master inconsolable, Zengzi keen on transmitting the supposed true teachings of Confucius and to whom is attributed the Book of Filial Piety, etc. -

Mencius on Becoming Human a Dissertation Submitted To

UNIVERSITY OF HAWNI LIBRARY MENCIUS ON BECOMING HUMAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN PHILOSOPHY DECEMBER 2002 By James P. Behuniak Dissertation Committee: Roger Ames, Chairperson Eliot Deutsch James Tiles Edward Davis Steve Odin Joseph Grange 11 ©2002 by James Behuniak, Jr. iii For my Family. IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With support from the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Hawai'i, the Harvard-Yenching Institute at Harvard University, and the Office of International Relations at Peking University, much of this work was completed as a Visiting Research Scholar at Peking Univeristy over the academic year 2001-2002. Peking University was an ideal place to work and I am very grateful for the support of these institutions. I thank Roger Ames for several years of instruction, encouragement, generosity, and friendship, as well as for many hours of conversation. I also thank the Ames family, Roger, Bonney, and Austin, for their hospitality in Beijing. I thank Geir Sigurdsson for being the best friend that a dissertation writer could ever hope for. Geir was also in Beijing and read and commented on the manuscript. I thank my committee members for comments and recommendations submitted over the course of this work. lowe a lot to Jim Tiles for prompting me to think through the subtler components of my argument. I take full responsibility for any remaining weaknesses that carry over into this draft. I thank my additional member, Joseph Grange, who has been a mentor and friend for many years. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, AUGUST 1966-JANUARY 1967 Zehao Zhou, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor James Gao, Department of History This dissertation examines the attacks on the Three Kong Sites (Confucius Temple, Confucius Mansion, Confucius Cemetery) in Confucius’s birthplace Qufu, Shandong Province at the start of the Cultural Revolution. During the height of the campaign against the Four Olds in August 1966, Qufu’s local Red Guards attempted to raid the Three Kong Sites but failed. In November 1966, Beijing Red Guards came to Qufu and succeeded in attacking the Three Kong Sites and leveling Confucius’s tomb. In January 1967, Qufu peasants thoroughly plundered the Confucius Cemetery for buried treasures. This case study takes into consideration all related participants and circumstances and explores the complicated events that interwove dictatorship with anarchy, physical violence with ideological abuse, party conspiracy with mass mobilization, cultural destruction with revolutionary indo ctrination, ideological vandalism with acquisitive vandalism, and state violence with popular violence. This study argues that the violence against the Three Kong Sites was not a typical episode of the campaign against the Four Olds with outside Red Guards as the principal actors but a complex process involving multiple players, intraparty strife, Red Guard factionalism, bureaucratic plight, peasant opportunism, social ecology, and ever- evolving state-society relations. This study also maintains that Qufu locals’ initial protection of the Three Kong Sites and resistance to the Red Guards were driven more by their bureaucratic obligations and self-interest rather than by their pride in their cultural heritage. -

Where Did All the Filial Sons Go?

CHAPTER 1 Where Did All the Filial Sons Go? In the year 73 BCE, the most powerful man in the Han empire, the General- in-Chief (da jiangjun 大將軍) Huo Guang 霍光 (d. 68 BCE), charged Liu He 劉賀 (ca. 92–59 BCE), the Imperial Heir Apparent, with ritual misconduct. The General called for Liu’s removal from power as the result of a scandal involving sex, alcohol, and a man ostensibly in mourning. In a memorial to the empress dowager, Huo enumerated the crimes of the eighteen-year-old Liu. While in mourning for his imperial predecessor, the young man indulged in such pastimes as visiting zoos and bringing entertainers into the palace, when music and dance were not only in poor taste, but also strictly forbid- den to mourners. He used public money for making gifts of concubines to his friends and imprisoned officials who tried to admonish him.1 Worse still, Liu ate meat, drank spirits, and engaged in sexual activity (all forbidden to mourners). In fact, while traveling to the capital, he ordered his subordinates to seize women on the road and load them into screened carriages. Upon his arrival in the capital, the debauchery continued, as Liu and his followers took liberties with women from the dead emperor’s harem. Acts such as these led Huo to conclude, not unreasonably, that the young man, though he wore the garments of deepest mourning, was “without sorrow or grief in his heart.”2 Such a lack of filial piety, Huo reminded the empress dowager, was the grav- est of crimes, and thus called for severe punishment and removal from power.3 Huo’s arguments met with imperial favor: not long afterwards, Liu’s riotous followers were executed, and he was duly removed as heir apparent and sent back to the provinces. -

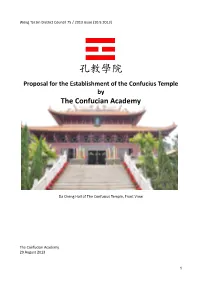

Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by the Confucian Academy

Wong Tai Sin District Council 75 / 2013 issue (10.9.2013) 孔教學院 Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by The Confucian Academy Da Cheng Hall of The Confucius Temple, Front View The Confucian Academy 29 August 2013 1 Content 1. Objectives ……………………………………………………….………………..……….…………… P.3 2. An Introduction to Confucianism …………………………………..…………….………… P.3 3. Confucius, the Confucius Temple and the Confucian Academy ………….….… P.4 4. Ideology of the Confucius Temple ………………………………..…………………….…… P.5 5. Social Values in the Construction of the Confucius Temple …………..… P.7 – P.9 6. Religious Significance of the Confucius Temple…………………..……….… P.9 – P.12 7. Cultural Significance of the Confucius Temple…………………………..……P.12- P.18 8. Site Selection ………………………………………………………………………………………… P.18 9. Gross Floor Area (GFA) of the Confucius Temple …………………….………………P.18 10. Facilities …………………………………………………………………….……………… P.18 – P.20 11. Construction, Management and Operation ……………….………………. P.20– P.21 12. Design Considerations ………………………………………………………………. P.21 – P.24 13. District Consultation Forums .…………………………………..…………….…………… P.24 14. Alignment with Land Use Development …….. …………………………….………… P.24 15. The Budget ……………………………………………………………………………………………P.24 ※ Wong Tai Sin District and the Confucius Temple …………………………….….... P.25 Document Submission……………………………………………………………………………….. P.26 Appendix 1. Volume Drawing (I) of the Confucius Temple ………………..……….P.27 Appendix 2. Volume Drawing (II) of the Confucius Temple …………….………….P.28 Appendix 3. Design Drawings of the Confucius Temple ……………………P.29 – P.36 2 Proposal for the Establishment of the Confucius Temple by the Confucian Academy 1. Objectives This document serves as a proposal for the construction of a Confucius Temple in Hong Kong by the Confucian Academy, an overview of the design and architecture of the aforementioned Temple, as well as a way of soliciting the advice and support from the Wong Tai Sin District Council and its District Councillors. -

Selections from Mencius, Books I and II: Mencius's Travels Persuading

MENCIUS Translation, Commentary, and Notes Robert Eno May 2016 Version 1.0 © 2016 Robert Eno This online translation is made freely available for use in not for profit educational settings and for personal use. For other purposes, apart from fair use, copyright is not waived. Open access to this translation, without charge, is provided at: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23423 Also available as open access translations of the Four Books The Analects of Confucius: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23420 Mencius: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23421 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23422 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23424 Cover illustration Mengzi zhushu jiejing 孟子註疏解經, passage 2A.6, Ming period woodblock edition CONTENTS Prefatory Note …………………………………………………………………………. ii Introduction …………………………………………………………………………….. 1 TEXT Book 1A ………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Book 1B ………………………………………………………………………………… 29 Book 2A ………………………………………………………………………………… 41 Book 2B ………………………………………………………………………………… 53 Book 3A ………………………………………………………………………………… 63 Book 3B ………………………………………………………………………………… 73 Book 4A ………………………………………………………………………………… 82 Book 4B ………………………………………………………………………………… 92 Book 5A ………………………………………………………………………………... 102 Book 5B ………………………………………………………………………………... 112 Book 6A ……………………………………………………………………………….. 121 Book 6B ……………………………………………………………………………….. 131 Book -

China: Promise Or Threat?

<UN> China: Promise or Threat? <UN> Studies in Critical Social Sciences Series Editor David Fasenfest (Wayne State University) Editorial Board Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (Duke University) Chris Chase-Dunn (University of California-Riverside) William Carroll (University of Victoria) Raewyn Connell (University of Sydney) Kimberlé W. Crenshaw (University of California, la, and Columbia University) Heidi Gottfried (Wayne State University) Karin Gottschall (University of Bremen) Mary Romero (Arizona State University) Alfredo Saad Filho (University of London) Chizuko Ueno (University of Tokyo) Sylvia Walby (Lancaster University) Volume 96 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/scss <UN> China: Promise or Threat? A Comparison of Cultures By Horst J. Helle LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the cc-by-nc License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover illustration: Terracotta Army. Photographer: Maros M r a z. Source: Wikimedia Commons. (https://goo.gl/WzcOIQ); (cc by-sa 3.0). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Helle, Horst Jürgen, author. Title: China : promise or threat? : a comparison of cultures / by Horst J. Helle. Description: Brill : Boston, [2016] | Series: Studies in critical social sciences ; volume 96 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016034846 (print) | lccn 2016047881 (ebook) | isbn 9789004298200 (hardback : alk. paper) | isbn 9789004330603 (e-book) Subjects: lcsh: China--Social conditions. -

Goldin, Prefinal.Indd

primacy of the situation paul r. goldin The Theme of the Primacy of the Situation in Classical Chinese Philosophy and Rhetoric here is a widespread misconception about the Confucian virtue T called shu ஏ, “reciprocity.” Conventionally, shu is explained as a variant of the Golden Rule (“Do unto others as you would have others do unto you”),1 an interpretation for which there seems to be very good textual warrant, inasmuch as Confucius himself is quoted in Analects xv/24 as saying that shu means “What you yourself do not desire, do not do unto others” աࢬլ, ֎ਜ࣍Գ.2 But the problem with letting Confucius’s own words speak for themselves is that for twenty-first- century readers this maxim leaves out an important qualification. In the context of early China, shu means doing unto others as you would have others do unto you, if you were in the same social situation as they.3 Otherwise, shu would require fathers to treat their sons in the same manner that their sons treat them — a practice that no Confucian has ever considered appropriate. Precisely this misunderstanding has 1 See, e.g., Herbert Fingarette, “Following the ‘One Thread’ of the Analects,” in Henry Rose- mont, Jr., and Benjamin I. Schwartz, eds., Studies in Classical Chinese Thought, Journal of the American Academy of Religion 47.3, Thematic Issue S (1979), pp. 373–405; H. G. Creel, “Dis- cussion of Professor Fingarette on Confucius,” in ibid., pp. 407–15; David S. Nivison, The Ways of Confucianism: Investigations in Chinese Philosophy, ed. Bryan W. -

Lijiao: the Return of Ceremonies Honouring

Special Feature s The Contemporary Revival of Confucianism e v i a Lijiao : The Return of t c n i e Ceremonies Honouring h p s c r Confucius in Mainland China e p SÉBASTIEN BILLIOUD AND JOËL THORAVAL Part of a larger project on the revival of Confucianism in Mainland China, this article explores the case of the Confucius ceremonies performed at the end of September each year in the city of Qufu, Shandong Province. In order to put things into perspective, it first traces the history of the cult at different periods of time. This is followed by a factual description of the events taking place during the so-called “Confucius festival,” which provides insight into the complexity of the issue and the variety of situations encountered. The contrast between the authorities and minjian Confucian revivalists, as well as their necessary interactions, ultimately illustrates the complex use and abuse of Confucius in post-Maoist China. ince the start of the new century it is possible to ob - ety of situations encountered. The contrast between the au - serve in Mainland China a growing interest in the thorities and minjian Confucian revivalists, as well as their Sremnants of Confucian tradition. Whereas such an in - necessary interactions, ultimately illustrates the complex use terest was previously confined within the academy, now it is and abuse of Confucius in post-Maoist China. In that re - in society that forms of Confucianism (with their sideline spect, the cult of Confucius in Qufu today perpetuates an an - dreams and reinventions) have become meaningful once cient tension that can be traced back to the imperial era and more. -

An Exploration of the Origin of Zhu Xi S Viewpoint on the Succession of The

࢈τϜНᏱൣ! ಒΫή 2010 Ԓ 06 У 75-116 ॳ ᜋ፤ख़ϟϸݚ˕˕ԨᐺၿಜᢏేྜՄᄇقᏑဒ፲ ചഈྜ ᄣ! ् Ѝφȃφȃφࡧȃ۞φϟ༉Ȃі፞Ꮡᚡᆏဒ፲ژ൞ȃȃऊȃȂ ȂᙾϟϜȂಥܼጃᇰᏑᏱϲోȄԨᐺܓᜋ࢈ݾᙾ࣐ᏑᏱȂໍՅӲᘫܼЗق ༮хᏑᏱԚ൸Ȅᔯଇіם๙ᏱȂڐпΡโ༉ٯȂقпȶၿಜȷϾѳਫᡞ ϛུມཋȂηٯȂȶၿಜȷޠܜ፞ᏑࡧՄᚡᆏጤસȂூُԨᐺٿп क़ၭȂпІܼٙᏑᏱᄃޠӬȂՅತᆺхᏑଢ൷ဒెޠ܉ϛ፞Ӽ྆ ϟϜȂሏໍึܓȂпІӲᘫܼЗܜЗூᇅᛅȂӶ࢈ݾᄃ፻ȃᏑᏱ༉ޠ፻࿌Ϝ ࡈᇲޠᜋقȂࣻϤᒋȂಥܼ२ᄻᏑᏱѭᢏȂԨᐺпȶၿಜȷԚΚᆎဒ፲ नෂՄᄇȂᄈܼޠހኅΩ໕ȄҐНᙥҦޠᇅᖑ݃ȂᇌᑗࢌεȂϘԥདЗ РӪȄޠఽྀԨᐺȶၿಜȷ፤ख़ծоԥΠ ᜱᗥມȈᏑᏱȃѳਫȃԨᐺȃၿಜȃЗܓ ጉԚѓȂ2010/05/18 ቸࢦႇȂ2010/06/02 ঔॐጉԞӈȄ 2010/03/31 ఁ௳Ȅقചഈྜ౫ᙜ࣐Ҵ࢈ݾτᏱϜН 76! ࢈τϜНᏱൣ! ಒΫή Analysis of the Song Scholars’ Discourses on the Genealogy of the Sages -- An Exploration of the Origin of Zhu Xi’s Viewpoint on the Succession of the Way (daotong) Chen Feng-yuan Abstract According to scholars of the Northern Song Dynasty, through its passage from Yao, Shun, Yu, and Tang to Confucius, Zengzi, Zisi, and Mencius, the genealogy of sages transformed from politics into Confucianism and then evolved further to mental character. In the process of transformation, the underlying meaning of Confucianism was finally confirmed. Zhu Xi used the Succession of the Way (daotong) to consolidate the system of the Four Books, while also applying Cheng Yi and Cheng Hao’s great learning to mold the achievements of Confucianism in the Song Dynasty. A reappraisal of the the development of Confucian thought since the Northern Song requires an investigation of the sequence of ideas inherited by Zhu Xi. The “Succession of the Way” is not a new term, nor is it a blending of various concepts. In fact, it is the accumulation of many scholars’ research and practice of Confucianism, in the areas of politics as well as mental character, which could be used to reconstruct the historical viewpoint of Confucianism. -

A Study of the Guodian Confucian Texts

Early Confucianism: A Study of the Guodian Confucian Texts Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Wong, Kwan Leung Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 06:38:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195186 EARLY CONFUCIANISM: A STUDY OF THE GUODIAN CONFUCIAN TEXTS by Kwan Leung Wong _______________________________ Copyright © Kwan Leung Wong 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Kwan Leung Wong entitled EARLY CONFUCIANISM: A STUDY OF THE GUODIAN CONFUCIAN TEXTS and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________________________________________________ Date: March 24, 2006 Jiang Wu Dissertation Chair _______________________________________________ Date: March 24, 2006 Donald Harper Dissetation Co-chair ________________________________________________ Date: March 24, 2006 Anna M. Shields Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement.