Developing a Meal-Planning Exchange List for Traditional Pakistani Dishes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Villa Breakfast

In Villa Breakfast For your convenience you can scan these QR codes to see our menu in your preferred language Chinese Russian Freshly Squeezed Juices THB 400 Orange Watermelon Carrot Thai Pomelo Melon Tomato Mango Papaya Cucumber Pineapple Apple Mixed Fruit Smoothies THB 450 Strawberry Peach Exotic Fruit Banana Mango Mixed Fruit Prices are Subject to 10% Service Charge and 7% Government Tax Healthy and Low Calorie (H). Organic (O). Vegetarian (V). Plant Based (PB). Gluten Free (GF). Dairy Free (DF). Spicy (S). Seasonal Fresh Cut Fruits THB 380 Choose Your 5 Favourite Fruits From Our List Mango Longan* Orange Green Apple Papaya Thai Pomelo Red Apple Passion Fruit Watermelon Green Grape Lychees* Black Grape Pineapple Pomegranate Bananas Rambutan* Mangosteen* Dragon Fruit Mandarin Rose Apple Guava *Subject to seasonal availability Prices are Subject to 10% Service Charge and 7% Government Tax Healthy and Low Calorie (H). Organic (O). Vegetarian (V). Plant Based (PB). Gluten Free (GF). Dairy Free (DF). Spicy (S). From The Bakery THB 890 Basket Freshly Baked Bread Croissants, Danish Pastry, Rolls, Toast, and Muffins Selection of Homemade Jams French Butter, Vanilla Butter Danish Collection THB 690 Freshly Baked Danish Pastries Home Style Muesli THB 380 Choose Your Favourite Traditional Bircher Muesli Muesli (GF) Berry Muesli Oatmeal Artisan Cheese Selection If you have a cheese preference please speak to your waiter Homemade Jams and Preserves Strawberry Jam Raspberry Jam Papaya Jam Passion Fruit Jam Apple Jam Mango Jam Kiwi Jam Coconut Jelly Apricot Jelly Mandarin Marmalade Pineapple Marmalade Pumpkin Marmalade Lemon Marmalade Prices are Subject to 10% Service Charge and 7% Government Tax Healthy and Low Calorie (H). -

Ingrouille, Kristina Title: Effect of Caffeinated Beverages Upon Breakfast Meal Consumption of University of Wisconsin-Stout Undergraduate Students

1 Author: Ingrouille, Kristina Title: Effect of Caffeinated Beverages upon Breakfast Meal Consumption of University of Wisconsin-Stout Undergraduate Students The accompanying research report is submitted to the University of Wisconsin-Stout, Graduate School in partial completion of the requirements for the Graduate Degree/ Major: MS in Food and Nutritional Sciences Research Advisor: Carol Seaborn, Ph.D. Submission Term/Year: Spring, 2013 Number of Pages: 51 Style Manual Used: American Psychological Association, 6th edition I understand that this research report must be officially approved by the Graduate School and that an electronic copy of the approved version will be made available through the University Library website I attest that the research report is my original work (that any copyrightable materials have been used with the permission of the original authors), and as such, it is automatically protected by the laws, rules, and regulations of the U.S. Copyright Office. My research advisor has approved the content and quality of this paper. STUDENT: NAME Kristina Ingrouille DATE: May 14, 2013 ADVISOR: (Committee Chair if MS Plan A or EdS Thesis or Field Project/Problem): NAME Carol Seaborn DATE: May 14, 2013 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---- This section for MS Plan A Thesis or EdS Thesis/Field Project papers only Committee members (other than your advisor who is listed in the section above) 1. CMTE MEMBER’S NAME: DATE: 2. CMTE MEMBER’S NAME: DATE: 3. CMTE MEMBER’S NAME: DATE: ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---- This section to be completed by the Graduate School This final research report has been approved by the Graduate School. Director, Office of Graduate Studies: DATE: 2 Ingrouille, Kristina. -

Foods with an International Flavor a 4-H Food-Nutrition Project Member Guide

Foods with an International Flavor A 4-H Food-Nutrition Project Member Guide How much do you Contents know about the 2 Mexico DATE. lands that have 4 Queso (Cheese Dip) 4 Guacamole (Avocado Dip) given us so 4 ChampurradoOF (Mexican Hot Chocolate) many of our 5 Carne Molida (Beef Filling for Tacos) 5 Tortillas favorite foods 5 Frijoles Refritos (Refried Beans) and customs? 6 Tamale loaf On the following 6 Share a Custom pages you’ll be OUT8 Germany taking a fascinating 10 Warme Kopsalat (Wilted Lettuce Salad) 10 Sauerbraten (German Pot Roast) tour of four coun-IS 11 Kartoffelklösse (Potato Dumplings) tries—Mexico, Germany, 11 Apfeltorte (Apple net) Italy, and Japan—and 12 Share a Custom 12 Pfefferneusse (Pepper Nut Cookies) Scandinavia, sampling their 12 Lebkuchen (Christmas Honey Cookies) foods and sharing their 13 Berliner Kränze (Berlin Wreaths) traditions. 14 Scandinavia With the helpinformation: of neigh- 16 Smorrebrod (Danish Open-faced bors, friends, and relatives of different nationalities, you Sandwiches) 17 Fisk Med Citronsauce (Fish with Lemon can bring each of these lands right into your meeting Sauce) room. Even if people from a specific country are not avail- 18 Share a Custom able, you can learn a great deal from foreign restaurants, 19 Appelsinfromage (Orange Sponge Pudding) books, magazines, newspapers, radio, television, Internet, 19 Brunede Kartofler (Brown Potatoes) travel folders, and films or slides from airlines or your local 19 Rodkal (Pickled Red Cabbage) schools. Authentic music andcurrent decorations are often easy 19 Gronnebonner i Selleri Salat (Green Bean to come by, if youPUBLICATION ask around. Many supermarkets carry a and Celery Salad) wide choice of foreign foods. -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

Make It Tonight Easy Dinner Download

Make It Tonight Easy Dinner Download MENU for the Week of OCTOBER 1, 2018 Monday Quick Beef Stew with Red Wine and Rosemary Tuesday Pork Tenderloin with Spicy Grilled Pepper Relish Wednesday Ramen Noodle Soup with Spinach and Poached Eggs Thursday Pan-Seared Chicken Thighs with Beer and Grainy Mustard Sauce Fiday Butter-Basted Spiced Cod with Polenta, paired with Edna Valley Chardonnay Sponsored by Monday : Tuesday : Wednesday : Thursday : Friday : Quick Beef Stew Pork Tenderloin with Ramen Noodle Soup Pan-Seared Chicken Butter-Basted Spiced with Red Wine and Spicy Grilled Pepper with Spinach and Thighs with Beer and Cod with Polenta Rosemary Relish Poached Eggs Grainy Mustard Sauce SHOPPING LIST FRESH PRODUCE MEAT AND DAIRY ITEMS 1 cup frozen pearl onions 2 medium lemons Two 12- to 16-oz. pork tenderloins 1 cup dry red wine 3/4 to 1 lb. russet potatoes One 1- to 1½-lb. thick rib-eye 2 Tbs. harissa paste 1 oz. (1 packed cup) baby spinach steak 1 Tbs. whole-grain mustard 4 oz. button mushrooms 8 small bone-in, skin-on chicken 1 Tbs. prepared horseradish 2 red, yellow, or orange bell thighs (4 to 5 oz. each) peppers (or a mix) 2 tsp. Worcestershire sauce Four 6-oz. pieces cod loin 1 small yellow onion 1 tsp. chili garlic sauce 2 large eggs 2 medium shallots Sriracha or other hot sauce 11 Tbs. unsalted butter 2 medium scallions Asian sesame oil 1 small piece fresh ginger PANTRY STAPLES 4 cloves garlic OTHER GROCERIES 3 Tbs. extra-virgin olive oil 1 small bunch fresh rosemary 6½ cups lower-salt chicken broth 3½ Tbs. -

THE HANDBOOK Your South Beach Success Starts Here!

THE HANDBOOK Your South Beach Success Starts Here! Instructions, food lists, recipes and exercises to lose weight and get into your best shape ever CONTENTS HOW TO USE THIS HANDBOOK You’ve already taken the biggest step: committing to losing weight and learning to live a life of strength, energy PHASE 1 and optimal health. The South Beach Diet will get you there, and this handbook will show you the way. The 14-Day Body Reboot ....................... 4 The goal of the South Beach Diet® program is to help Diet Details .................................................................6 you lose weight, build a strong and fit body, and learn to Foods to Enjoy .......................................................... 10 live a life of optimal health without hunger or deprivation. Consider this handbook your personal instruction manual. EXERCISE: It’s divided into the three phases of the South Beach Beginner Shape-Up: The Walking Workouts ......... 16 Diet® program, color-coded so it’ll be easy to locate your Walking Interval Workout I .................................... 19 current phase: Walking Interval Workout II .................................. 20 PHASE 1 PHASE 2 PHASE 3 10-Minute Stair-Climbing Interval ...........................21 What you’ll find inside: PHASE 2 • Each section provides instructions on how to eat for that specific phase so you’ll always feel confident that Steady Weight Loss ................................. 22 you’re following the program properly. Diet Details .............................................................. 24 • Phases 1 and 2 detail which foods to avoid and provide Foods to Enjoy ......................................................... 26 suggestions for healthy snacks between meals. South Beach Diet® Recipes ....................................... 31 • Phase 2 lists those foods you may add back into your diet and includes delicious recipes you can try on EXERCISE: your own that follow the healthy-eating principles Beginner Body-Weight Strength Circuit .............. -

Aromatic Sauces Naan Breads

MENU DEAR GUESTS, Pakistani cuisine is a mixture of South Asian culinary traditions, characterized by a large variety and richness of flavours. In Pakistan, the dishes vary greatly depending on the region from which they come from, thus reflecting the ethnic and cultural diversity of the country. The dishes are tasty, full of aromas and spices. The cuisine comes from the culinary traditions of agricultural, hard-working people, which is why it can be fatty and caloric. Punjabi cuisine is dominated by meat bathed in thick sauces with a large amount of aromatic spices, onions, garlic and stewed vegetables. You can dip naan bread in the sauces or try Pakistani basmati rice. The taste of the sauces depends on the composition of spices used (masal) and different additives. Our restaurant serves authentic Pakistani and Indian cuisine. MENU SYMBOLS Gluten-free Hotness level 1 to 3 Vegetarian Perfect for kids You can choose between plain naan bread or rice to accompany your main dish (both free of charge). Please be advised that the hotness level can be customized, we also modify the dishes to eliminate the allergens. Please inform us upon ordering. PLEASE PAY ATTENTION TO THE HOTNESS OF THE DISHES. WE USE A BLEND OF FOR A STARTER PAKISTANI CHILLIES ORDER A SNACK AND WHICH ARE REALLY SPICY SNACKS CHOOSE A SAUCE FOR IT 1. ALOO PAKORA 150 G 16 PLN 8. ONION BHAJI 8 PIECES 14 PLN Deep-fried potatoes Deep fried onions, coated in pea flour dough. coated in pea flour 2. BAINGAN PAKORA 150 G 16 PLN 9. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

MENU DEAR CUSTOMERS, Pakistani Cuisine Is a Mixturedrodzy of South Przyjaciele Asian Culinary Traditions, Characterized by a Large Variety and Richness of Flavours

NEW MENU DEAR CUSTOMERS, Pakistani cuisine is a mixtureDrodzy of South Przyjaciele Asian culinary traditions, characterized by a large variety and richness of flavours. Pakistani dishes vary greatly depending on the region of origin, thus reflecting the ethnic and cultural diversity of the country. All dishes are tasty, full of aromas and spices. The cuisine comes from the culinary traditions of agricultural, hard-working people, which is why it can be fatty and caloric. The Punjabu cuisine is dominated by meat bathed in thick sauces, with the addition of a large amount of aromatic spices, onions, garlic and stewed vegetables. You can dip Naan bread in the sauces or try Pakistani basmati rice. The taste of sauces depends on the composition and variation of the spices (masala) used. Our restaurant serves authentic Pakistani and Indian cuisine. The dishes are prepared by chef Falak Shair. MENU SYMBOLS gluten free hotness vege perfect for kids novelty You can choose between plain naan bread or rice to accompany your main dish. Please be advise that the hotness level can be customized, we also modify the dishes to eliminate the allergens. Please inform us upon ordering. PLEASE DO PAY ATTENTION TO THE HOTNESS OF DISHES, WE USE A MIXTURE OF PAKISTANI CHILLIES, WHICH ORDER A SNACK AND CHOOSE ARE REALLY SPICY! SNACKS A SAUCE TO ACCOMPANY IT 1. ONION BHAJI 6 PCS. 12 PLN 7. FISH PAKORA 7 PCS. 20 PLN Deep fried onion in pea flour batter. Deep fried fish in pea flour batter. 2. GOBI PAKORA 8 PCS. 14 PLN 8. PRAWN PAKORA 8 PCS. -

Roti As Part of Food Exchange List

IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science (IOSR-JNHS) e-ISSN: 2320–1959.p- ISSN: 2320–1940 Volume 4, Issue 3 Ver. III (May. - Jun. 2015), PP 87-90 www.iosrjournals.org Estimation of Macronutrient Content of Traditional Pakistani Chapatti/ Roti as Part of Food Exchange List Ms. Mahnaz Nasir Khan1, Dr. Samia Kalsoom2, Dr. Ayyaz Ali Khan3 1(Assistant Professor, Food Science and Human Nutrition, Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore, Pakistan) 2(Professor, Government College of Home Economics, Lahore, Pakistan) 3(Doctor, Federal Postgraduate Medical Institute, Shaikh Zayed Medical Complex, Lahore, Pakistan) Abstract: This is a small base-line study where the researcher has made a unique attempt to disseminate the varying size of chapatti into the exchange list. Chapatti as it is a staple food of Pakistan and was assessed for its size and corresponding weight so that it could be incorporated as part of the carbohydrate exchange list. Though chapatti is served with the main course of every Pakistani cuisine yet its size and weight has not been standardized and difference in size and weight will lead to varying nutrient content and consequently number of exchanges. Chapattis of three different sizes were prepared in the Food Laboratory of Food Science & Human Nutrition Department, Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore. 9 experiments were carried out and three chapattis large, medium and small were prepared using 100grams, 75 grams and 50 grams of dry flour respectively. The results revealed that small chapatti (6inch diameter) contributed 37.5 grams of carbohydrate which in turn were converted to 2.5 carbohydrate exchanges. -

Three Colomns-ML Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results

Three colomns-ML Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results DBA CUISINE DESCRIPTION DUNKIN Donuts ALL ABOUT INDIAN FOOD Indian CHARLIES SPORTS BAR Bottled Beverages MIMMO Italian SUENOS AMERICANO BAR Spanish RESTAURANT ANN & TONY'S RESTAURANT Italian GREEN BEAN CAFE Coffee/Tea PORTO BELLO PIZZERIA & Pizza RESTAURANT GUESTHOUSE RESTAURANT Eastern European CALEXICO CARNE ASADA Mexican JOHNNY UTAHS American RUMOURS American FORDHAM RESTAURANT American HONG KONG CAFE CHINESE Chinese RESTAURANT ASTORIA SEAFOOD & GRILL Seafood SUP CRAB SEAFOOD RESTAURANT Chinese SWEETCATCH POKE Hawaiian SWEETCATCH POKE Hawaiian Page 1 of 488 09/29/2021 Three colomns-ML Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results INSPECTION DATE 11/18/2019 09/15/2021 11/24/2018 03/12/2020 01/03/2020 02/19/2019 01/16/2020 07/06/2017 04/24/2018 04/19/2018 06/20/2018 12/12/2019 09/10/2019 05/14/2018 08/19/2019 08/27/2019 06/24/2019 06/24/2019 Page 2 of 488 09/29/2021 Three colomns-ML Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results KAHLO Mexican 52ND SUSHI Japanese EL COFRE RESTAURANT Latin American CARVEL Frozen Desserts CHOPSTICKS Chinese CATRIA MODERN ITALIAN Italian CATRIA MODERN ITALIAN Italian TAGLIARE PIZZA DELTA TERMINAL American OVERLOOK American BILLIARD COMPANY American BOCADITO BISTRO Eastern European FINN'S BAGELS Coffee/Tea FINN'S BAGELS Coffee/Tea CHUAN TIAN XIA Chinese LA POSADA MEXICAN FOOD Mexican CHINA STAR QUEENS CHINESE Chinese RESTAURANT AC HOTEL NEW YORK DOWNTOWN American NEWTOWN Middle Eastern NO.1 CALLE 191 PESCADERIA -

Galiee-Style-Fish-Kebabs-2.Pdf

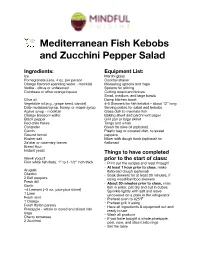

Mediterranean Fish Kebobs and Zucchini Pepper Salad Ingredients: Equipment List: Ice Martini glass Pomegranate juice, 4 oz. per person Cocktail shaker Orange flavored sparkling water - mocktail Measuring spoons and cups Vodka - citrus or unflavored Spoons for stirring Cointreau or other orange liqueur Cutting board and knives Small, medium, and large bowls Olive oil Damp kitchen towel Vegetable oil (e.g., grape seed, canola) 4-5 Skewers for fish kebabs - about 12” long Date molasses/syrup, honey, or maple syrup Serving plates for salad and kebobs Agave syrup - mocktail Glass dish to marinate fish Orange blossom water Baking sheet and parchment paper Black pepper Grill pan or large skillet Red chile flakes Tongs and whisk Coriander Brush for olive oil (optional) Cumin Plastic bag or covered dish, to sweat Ground fennel peppers Kosher salt Mixer with dough hook (optional) for Za’atar or rosemary leaves flatbread Bread flour Instant yeast Things to have completed Greek yogurt prior to the start of class: Firm white fish filets, 1” to 1-1/2” inch thick • Print out the recipes and read through! • At least 1 hour prior to class, make Arugula flatbread dough (optional) Cilantro • Soak skewers for at least 30 minutes, if 2 Bell peppers using wood/bamboo skewers Fresh dill • About 30 minutes prior to class, rinse Garlic fish in water, pat dry and cut in cubes. ~4 Lemons (~5 oz. juice plus slices) Sprinkle lightly with salt and leave 1 Lime uncovered on a plate in the refrigerator Fresh mint • Preheat oven to 425°F 1 Orange • Preheat grill, if using Fresh