Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' Alcestis

GOLDFARB, BARRY E., The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' "Alcestis" , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 33:2 (1992:Summer) p.109 The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' Alcestis Barry E. Goldfarb 0UT ALCESTIS A. M. Dale has remarked that "Perhaps no f{other play of Euripides except the Bacchae has provoked so much controversy among scholars in search of its 'real meaning'."l I hope to contribute to this controversy by an examination of the philosophical issues underlying the drama. A radical tension between the values of philia and xenia con stitutes, as we shall see, a major issue within the play, with ramifications beyond the Alcestis and, in fact, beyond Greek tragedy in general: for this conflict between two seemingly autonomous value-systems conveys a stronger sense of life's limitations than its possibilities. I The scene that provides perhaps the most critical test for an analysis of Alcestis is the concluding one, the 'happy ending'. One way of reading the play sees this resolution as ironic. According to Wesley Smith, for example, "The spectators at first are led to expect that the restoration of Alcestis is to depend on a show of virtue by Admetus. And by a fine stroke Euripides arranges that the restoration itself is the test. At the crucial moment Admetus fails the test.'2 On this interpretation 1 Euripides, Alcestis (Oxford 1954: hereafter 'Dale') xviii. All citations are from this editon. 2 W. D. Smith, "The Ironic Structure in Alcestis," Phoenix 14 (1960) 127-45 (=]. R. Wisdom, ed., Twentieth Century Interpretations of Euripides' Alcestis: A Collection of Critical Essays [Englewood Cliffs 1968]) 37-56 at 56. -

Download Notes 10-04.Pdf

Can you kill a god? Can he feel pain? Can you make him bleed? What do gods eat? Does Zeus delegate authority? Why does Zeus get together with Hera? Which gods are really the children of Zeus and Hera? Anthropomorphic Egyptian Greek ἡ ἀμβροσία ambrosia τὸ νέκταρ nectar ὁ ἰχώρ ichor Games and Traditions epichoric = local tradition Panhellenic = common, shared tradition Dumézil’s Three Functions of Indo-European Society (actually Plato’s three parts of the soul) religion priests τὀ λογιστικόν sovereignty 1 kings (reason) justice τὸ θυμοειδές warriors military 2 (spirit, temper) craftsmen, production τὸ ἐπιθυμητικόν farmers, economy 3 (desire, appetite) herders fertility Gaia Uranus Iapetus X Cœus Phœbe Rhea Cronos Atlas Pleione Leto gods (next slide) Maia Rhea Cronos Aphrodite? Hestia Hades Demeter Poseidon Hera Zeus Ares (et al.) Maia Leto Hephæstus Hermes Apollo Artemis Athena ZEUS Heaven POSEIDON Sea HADES Underworld ἡ Ἐστία HESTIA Latin: Vesta ἡ Ἥρα HERA Latin: Juno Boōpis Cuckoo Cow-Eyed (Peacock?) Scepter, Throne Argos, Samos Samos (Heraion) Argos Heraion, Samos Not the Best Marriage the poor, shivering cuckoo the golden apples of the Hesperides (the Daughters of Evening) honeymoon Temenos’ three names for Hera Daidala Athena Iris Hera Milky Way Galaxy Heracles Hera = Zeus Hephæstus Ares Eris? Hebe Eileithyia ὁ Ζεύς, τοῦ Διός ZEUS Latin: Juppiter Aegis-bearer Eagle Cloud-gatherer Lightning Bolt Olympia, Dodona ἡ ξενία xenia hospitality ὁ ὅρκος horcus ἡ δίκη oath dicē justice Dodona Olympia Crete Dodona: Gaia, Rhea, Dione, Zeus Olympia: -

A Philosophical Inquiry Into the Development of the Notion of Kalos Kagathos from Homer to Aristotle

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2006 A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle Geoffrey Coad University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Coad, G. (2006). A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle (Master of Philosophy (MPhil)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/13 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NOTION OF KALOS KAGATHOS FROM HOMER TO ARISTOTLE Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Geoffrey John Coad School of Philosophy and Theology University of Notre Dame, Australia December 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Declaration v Acknowledgements vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Fish Hook and Some Other Examples 6 The Sun – The Source of Beauty 7 Some Instances of Lack of Beauty: Adolf Hitler and Sharp Practices in Court 9 The Kitchen Knife and the Samurai Sword 10 CHAPTER 2: Homer 17 An Historical Analysis of the Phrase Kalos Kagathos 17 Herman Wankel 17 Felix Bourriott 18 Walter Donlan 19 An Analysis of the Terms Agathos, Arete and Other Related Terms of Value in Homer 19 Homer’s Purpose in Writing the Iliad 22 Alasdair MacIntyre 23 E. -

A Level Classical Civilisation Candidate Style Answers

Qualification Accredited A LEVEL Candidate style answers CLASSICAL CIVILISATION H408 For first assessment in 2019 H408/11: Homer’s Odyssey Version 1 www.ocr.org.uk/alevelclassicalcivilisation A Level Classical Civilisation Candidate style answers Contents Introduction 3 Question 3 4 Question 4 8 Essay question 12 2 © OCR 2019 A Level Classical Civilisation Candidate style answers Introduction OCR has produced this resource to support teachers in interpreting the assessment criteria for the new A Level Classical Civilisation specification and to bridge the gap between new specification’s release and the availability of exemplar candidate work following first examination in summer 2019. The questions in this resource have been taken from the H408/11 World of the Hero specimen question paper, which is available on the OCR website. The answers in this resource have been written by students in Year 12. They are supported by an examiner commentary. Please note that this resource is provided for advice and guidance only and does not in any way constitute an indication of grade boundaries or endorsed answers. Whilst a senior examiner has provided a possible mark/level for each response, when marking these answers in a live series the mark a response would get depends on the whole process of standardisation, which considers the big picture of the year’s scripts. Therefore the marks/levels awarded here should be considered to be only an estimation of what would be awarded. How levels and marks correspond to grade boundaries depends on the Awarding process that happens after all/most of the scripts are marked and depends on a number of factors, including candidate performance across the board. -

4. Older Olympians.Key

The Older Olympians LVV4U1 - GRADE 12 CLASSICAL CIVILIZATION - MR. A. WITTMANN UNIT 2 – LECTURE 4 1 6 children of Kronos and Rhea are the first Olympians… Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Hestia, Hades Aphrodite born of his severed genitals of Uranus 2 God Competence God Competence 1. Zeus Storms 6. Apollo Wisdom 2. Hera Family 7. Artemis Hunt 3. Hestia Hearth 8. Hephaestus Forge 4. Demeter Harvest 9. Athena Knowledge Hades Underworld 10. Ares War 5. Poseidon Sea 11. Hermes Trade 12. Aphrodite Sex 3 Zeus, Lord of the Sky Evolved from Indo-European sky god Dyeus pater (Sky Father) Dyaus pitar (Indian) Dyeus (Iranian) Ju-pitar or Jove (Roman) Tues (Germanic) Sky, high places, thunder/lighting, Bull, eagle, oak, aegis (goat skin) epithets: Nephelegereta (cloud gatherer), Kataibates (descending) 4 5 Zeus, King of Gods & Men Father of all Xenia (guest/host, friendship/ hospitality) Justice, tradition, custom not modern justice heiros gamos sacred marriage with Hera… 1. Uranus + Gaea 2. Kronos + Rhea 3. Zeus + Hera 6 7 Zeus, King of Gods & Men Infidelity with goddess allegorizes the Indo- European male sky god’s triumph over local indigenous female earth goddesses Also illustrates how he organized the natural universe & est. human customs & traditions Metis (cleverness) = Athena (strength and judgment) Themis (established law) = Horae (seasons) Moerae (fates) Eurynomê (Custom) = Eirenê (Peace), Dikê (justice), 3 Graces 8 Zeus, King of Gods & Men Infidelity with mortals explains the origins of heroes & kings Legitimizes local kings and rulering families -

“100% Sanctification – Guaranteed” – Part 2 100% Sanctification

THE SECOND EPISTLE OF PETER TO THE CHURCH OF THE DISPERSION THROUGHOUT THE WORLD 2 PETER CHAPTER 1:5-9 MEDIA REFERENCE NUMBER SMX995 OCTOBER 27, 2019 THE TITLE OF THE MESSAGE: “100% Sanctification – Guaranteed” – Part 2 SUBJECT TOPICALLY REFERENCED UNDER: Faithfulness, Finishing, Church, Christianity, Discipleship 2 Peter 1:5-9 But also for this very reason, giving all diligence, add to your faith virtue, to virtue knowledge, 6 to knowledge self-control, to self-control perseverance, to perseverance godliness, 7 to godliness brotherly kindness, and to brotherly kindness love. 8 For if these things are yours and abound, you will be neither barren nor unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. 9 For he who lacks these things is shortsighted, even to blindness, and has forgotten that he was cleansed from his old sins. 100% Sanctification – Guaranteed! We have read throughout the Old Testament that God called His people to be set apart from this world and to be set apart for Him That Old Testament Requirement is Fulfilled in the New Testament Relationship And in Peter’s Day - The Early Church was Increasingly Thankful for that. It’s success / It’s effect / It’s influence / It’s earthly calling / From its heavenly position. 1 Thessalonians 5:23-24 Now may the God of peace Himself sanctify you completely; and may your whole spirit, soul, and body be preserved blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. 24 He who calls you is faithful, who also will do it. Reviewing Part 1 of Our Previous Teaching 100% Sanctification – Guaranteed! 1.) Means that we co-operate with God vs. -

The Name of Penelope Whallon, William Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Jan 1, 1960; 3, 2; Proquest Pg

The Name of Penelope Whallon, William Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Jan 1, 1960; 3, 2; ProQuest pg. 57 The Name of Penelope William W hallon T HE TALE OF ODYSSEUS' RETURN would have been very different if his wife had not been known as Penelope. For the Homeric poems came from an age of aural etymologizing,l the minstrels who perfected the poems throughout centuries of storytelling found proper nouns as meaningful as common nouns, and certain phonetic associations at first fortuitous became inevitable. Shakespeare's Juli et by any other name than Capulet would have had greater fortune in love, but Penelope's name is even more vitally related to her biography. Now it is an obvious fact that a language built upon a rather small number of phonemes is almost necessarily going to include homonyms, and correspondence of sound alone is insufficient to indicate words as cognate. In present-day Norwegian, for example, the word for the duck, Anda (where the dental stop is no longer pronounced), does not compel any kind of dark reminiscence of the girl named Anna, and likewise the duck 7TTJVEAoljl need not be thought germane to Penelope,2 unless in the similarity there is a remnant from the dawn of time, when in a beast epic Penelope might actually have been a duck, Athene an owl, Hera a heifer, and Apollo a wolf. In the Homeric poems we possess, the 7TTJv€Aoljl and Penelope have no semantic relationship, and the coincidence of identical syllables is unimportant. Another word, however, has been commonly observed as apparently akin to the name of Pe nelope, and may have had a crucial bearing upon her career: this IMost notably in Od. -

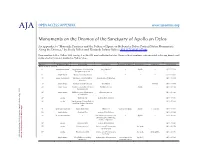

Supplemental Content: Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary Of

AJA OPEN ACCESS: APPENDIX www.ajaonline.org Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary of Apollo on Delos An appendix to “Honorific Practices and the Politics of Space on Hellenistic Delos: Portrait Statue Monuments Along the Dromos,” by Sheila Dillon and Elizabeth Palmer Baltes (AJA 117 [2013] 207–46). Base numbers follow Vallois 1923 (see fig. 3 in the AJA print-published article). Bases without numbers were recorded as having been found in the area but were not marked on Vallois’ plan. Base No. Monument Type Honorand(s) Dedicator(s) Reason(s) for Honor Dedicated to Sculptor(s) Reference(s) Bases set up ca. 250–200 5 equestrian statue Epigenes, son of Andron, the King Attalos I – Apollo – IG 11 4 1109 Pergamene general 8 single statue Donax, son of Apollonios – – – – IG 11 4 1202 16 group monument Aischylo(. .) and his father, Mennis, son of Nikarchos – – – IG 11 4 1168 Nikarchos 19 single statue female, Hellenistic queen? the Delians – – Thoinias IG 11 4 1088 20 single statue Autokles, son of Ainesidemos, Autokles, his son – Apollo – IG 11 4 1194 from Chalcidia 117.2) 25 single statue Phildemos, son of Pythermos Eumedes, his son – – – IG 11 4 1193 of Chalcedon 27 exedra family group demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1090 33 exedra family group of Jason, Eukleia, – – – – IG 11 4 1203 Timokleia, Straton, Timokleia, Sillis 41 victory monument Gallic dedication Attalos I(?) victory over Gauls Apollo (. .)epoiei IG 11 4 1110 50c single statue Aichmokritos demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1094 American Journal of Archaeology American 53 -

The Oracle and Cult of Ares in Asia Minor Matthew Gonzales

The Oracle and Cult of Ares in Asia Minor Matthew Gonzales ERODOTUS never fails to fascinate with his rich and detailed descriptions of the varied peoples and nations H mustered against Greece by Xerxes;1 but one of his most tantalizing details, a brief notice of the existence of an oracle of Ares somewhere in Asia Minor, has received little comment. This is somewhat understandable, as the name of the proprietary people or nation has disappeared in a textual lacuna, and while restoring the name of the lost tribe has ab- sorbed the energies of some commentators, no moderns have commented upon the remarkable and unexpected oracle of Ares itself. As we shall see, more recent epigraphic finds can now be adduced to show that this oracle, far from being the fantastic product of logioi andres, was merely one manifestation of Ares’ unusual cultic prominence in south/southwestern Asia Minor from “Homeric” times to Late Antiquity. Herodotus and the Solymoi […] 1 The so-called Catalogue of Forces preserved in 7.61–99. In light of W. K. Pritcéhesttp’s¤ dtahwo rodu¢g h» mreofbuota˝tnioanws eo‰xf osunc hs mscihkorlãarws, aksa O‹ .p rAorbmÒalyoru, wD . FehdlÊinog ,l aunkdio Se.r Wg°eastw, ßwkhaos steoekw teo‰x dei,s c§rped‹ idt ¢th teª asuit hkoerfitay loªf sHie krordãontuesa o n thixs ãanldk eoath:e pr rpÚowin dts¢, tIo w›silli skimrãplnye rseif eŒr ttãhe t ree kadae‹r kto° rPerait cphreotts’s∞ tnw ob omÚawj or trexatãmleknetas ,o f t§hpe∞irs waonr k,d S¢t udkieas i‹n AlnÒcifenot i:G reetkå Two podg¢ra phkyn IÆVm (aBwe rk=eãleky e1s9i8 2) 23f4–o2in85ik a°nodi sTih ek Laiatre Silch¤xoola otf oH. -

Guest-Host Relationships in Apuleius' Metamorphoses

Discentes Volume 1 Issue 1 Volume 1, Issue 1 Article 7 2016 Xenia Perverted: Guest-host Relationships in Apuleius' Metamorphoses Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Classics Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation . 2016. "Xenia Perverted: Guest-host Relationships in Apuleius' Metamorphoses." Discentes 1, (1):59-69. https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal/vol1/iss1/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal/vol1/iss1/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Xenia Perverted: Guest-host Relationships in Apuleius' Metamorphoses This article is available in Discentes: https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal/vol1/iss1/7 Xenia Perverted: Guest-host Relationships in Apuleius' Metamorphoses By Noreen Sit The relationships between guests and hosts in Apuleius' Metamorphoses are interesting because of their parallels and contrasts with similar relationships in epic. Much like Homer's tale of the wandering Odysseus, Apuleius' novel follows the adventures of Lucius who encounters many lands and people during his travels. In some cases, Lucius is the guest; at other times, he is an observer. Xenia appears in the Metamorphoses in various manifestations, but it is frequently violated. Apuleius takes the familiar theme of xenia and, by perverting it, challenges the tradition for his audience's entertainment. Xenia is the term that refers to the relationship between guest and host. Good xenia is characterized by a host's willingness to accommodate a guest, no matter the circumstances, and a guest's promise that he will return the favor. -

The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad

The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad by Eirene Seiradaki A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Classics University of Toronto © Copyright by Eirene Seiradaki (2014) “The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad ” Eirene Seiradaki Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This dissertation offers an interpretation of the re-exchange of the first set of Achilles’ arms in the Iliad by gift, loan, capture, and re-capture. Each transfer of the arms is examined in relation to the poem’s dramatic action, characterisation, and representation of social institutions and ethical values. Modern anthropological and economic approaches are employed in order to elucidate standard elements surrounding certain types of exchange. Nevertheless, the study primarily involves textual analysis of the Iliadic narratives recounting the circulation-process of Achilles’ arms, with frequent reference to the general context of Homeric exchange and re-exchange. The origin of the armour as a wedding gift to Peleus for his marriage to Thetis and its consequent bequest to Achilles signifies it as the hero’s inalienable possession and marks it as the symbol of his fate in the Iliad . Similarly to the armour, the spear, a gift of Cheiron to Peleus, is later inherited by his son. Achilles’ own bond to Cheiron makes this weapon another inalienable possession of the hero. As the centaur’s legacy to his pupil, the spear symbolises Achilles’ awareness of his coming death. In the present time of the Iliad , ii Achilles lends his armour to Patroclus under conditions that indicate his continuing ownership over his panoply and ensure the safe use of the divine weapons by his friend. -

THE LAND of MYTH MECHANICS: This Adventure Was Designed As a ‘One Shot’ (I.E

2 3 ἄνδρα µοι ἔννεπε, µοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς µάλα πολλὰ πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσεν· πολλῶν δ᾽ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω, πολλὰ δ᾽ ὅ γ᾽ ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυµόν, ἀρνύµενος ἥν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων. Homer’s Odyssey, Book 1, Lines 1-5 (ΟΜΗΡΟΥ ΟΔΥΣΣΕΙΑ, ΡΑΨΟΔΙΑ 1, ΣΤΙΧΟΙ 1-5) CREDITS INDEX Credits – The Land of Myth™ Team Written & Designed by: John R. Haygood Art Direction: George Skodras, Ali Dogramaci Who We Are .............................................................................................. 6 Cover Art: Ali Dogramaci What is this Product ................................................................................. 6 Proofreading & Editing: Vi Huntsman (MRC) This is a product created by Seven Thebes in collaboration with the Getty Museum Introduction ................................................................................................ 7 in Los Angeles, USA. Special thanks for the many hours of game testing and brainstorming: Safety and Consent .................................................................................. 10 Thanasis Giannopoulos, Alexandros Stivaktakis, Markos Spanoudakis About This Adventure Module .............................................................. 12 First Edition First Release: November 2020 Telemachos and His Quest ................................................................... 24 Character Sheets ...................................................................................... 26 Playtest Material V0.3 Please note that this