Eros, Piety, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Philosophical Inquiry Into the Development of the Notion of Kalos Kagathos from Homer to Aristotle

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2006 A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle Geoffrey Coad University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Coad, G. (2006). A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle (Master of Philosophy (MPhil)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/13 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NOTION OF KALOS KAGATHOS FROM HOMER TO ARISTOTLE Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Geoffrey John Coad School of Philosophy and Theology University of Notre Dame, Australia December 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Declaration v Acknowledgements vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Fish Hook and Some Other Examples 6 The Sun – The Source of Beauty 7 Some Instances of Lack of Beauty: Adolf Hitler and Sharp Practices in Court 9 The Kitchen Knife and the Samurai Sword 10 CHAPTER 2: Homer 17 An Historical Analysis of the Phrase Kalos Kagathos 17 Herman Wankel 17 Felix Bourriott 18 Walter Donlan 19 An Analysis of the Terms Agathos, Arete and Other Related Terms of Value in Homer 19 Homer’s Purpose in Writing the Iliad 22 Alasdair MacIntyre 23 E. -

Fall 2018 Volume 45 Issue 1

Fall 2018 Volume 45 Issue 1 3 Matthew S. Brogdon “Who Would Be Free, Themselves Must Strike the Blow”: Revolt and Rhetoric in Douglass’s Heroic Slave and Melville’s Benito Cereno 25 Ariel Helfer Socrates’s Political Legacy: Xenophon’s Socratic Characters in Hellenica I and II 49 Lorraine Smith Pangle The Radicalness of Strauss’s On Tyranny 67 David Polansky & With Steel or Poison: Daniel Schillinger Machiavelli on Conspiracy Book Reviews: 87 Ingrid Ashida Persian Letters by Montesquieu 93 Kevin J. Burns Legacies of Losing in American Politics by Jeffrey Tulis and Nicole Mellow 97 Peter Busch Montesquieu and the Despotic Ideas of Europe by Vickie B. Sullivan 103 Rodrigo Chacón The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World by Oona A. Hathaway and Scott J. Shapiro 109 Bernard J. Dobski Shakespeare’s Thought: Unobserved Details and Unsuspected Depths in Thirteen Plays by David Lowenthal 119 Elizabeth C’ de Baca Eastman The Woman Question in Plato’s “Republic” by Mary Townsend 125 Michael P. Foley The Fragility of Consciousness: Faith, Reason, and the Human Good by Frederick Lawrence 129 Raymond Hain The New Testament: A Translation by David Bentley Hart 135 Thomas R. Pope Walker Percy and the Politics of the Wayfarer by Brian A. Smith Doubting Progress: Two Reviews 141 Lewis Hoss A Road to Nowhere: The Idea of Progress and Its Critics 147 Eno Trimçev by Matthew W. Slaboch ©2018 Interpretation, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the contents may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publisher. -

1-Pgi-Apuleius6634 Finl

Index This online index is a much fuller version than the index that was abbre - viated for print. Like the print index, the online index has a number of goals beyond the location of proper names. For some names and technical terms it serves as a glossary and provides notes; for geograph - ical items it provides references to specific maps. But it is primarily de - signed to facilitate browsing. Certain key terms (sadism/sadistic, salvation/salvific/savior, sticking one’s nose in) can be appreciated for the frequency of their occurrence and have not been subdivided. Certain plot realities have been highlighted (dogs, food, hand gestures, kisses, processions, roses, shackles and chains, slaves, swords); certain themes and motifs have been underlined (adultery, disguise, drama, escape, gold, hair, hearth and home, madness, suicide); some quirks of the translation have been isolated (anachronisms, Misericordia! ); minu - tiae of animals, plants, language have been cataloged (deer, dill, and der - ring-do). The lengthy entry on Lucius tries to make clear the multiplicities of his experience. By isolating the passages in which he ad - dresses himself, or speaks of “when he was Lucius,” I hope to make the difficult task of determining whether the man from Madauros is really the same as Lucius the narrator, or the same as Apuleius the author, a little bit easier. abduction, 3.28–29, 4.23–24, 4.26; Actium (port in Epirus; site of Augus - dream of, 4.27 tus’ naval victory over Antony and Abstinence (Sobrietas, a goddess), 5.30; Cleopatra; Map -

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife Joel P. Christensen Brandeis University [email protected] Abstract This article examines the development of the theme of eris in Hesiod and Homer. Start- ing from the relationship between the destructive strife in the Theogony (225) and the two versions invoked in the Works and Days (11–12), I argue that considering the two forms of strife as echoing zero and positive sum games helps us to identify the cultural and compositional force of eris as cooperative competition. After establishing eris as a compositional theme from the perspective of oral poetics, I then argue that it develops from the perspective of cosmic history, that is, from the creation of the universe in Hes- iod’s Theogony through the Homeric epics and into its double definition in the Works and Days.To explore and emphasize how this complementarity is itself a manifestation of eris, I survey its deployment in our major extant epic poems. Keywords eris – competition – conflict – poetics – rivalry In Cypria fr. 1, Zeus fans “the flames of the great strife of the Trojan war / to lighten the [earth’s] burden with death” (ῥιπίσσας πολέμου μεγάλην ἔριν Ἰλιακοῖο, 5).* Similarly, in Hesiod (fr. 204 M-W), when strife divides the gods at the birth of Hermione—“all the gods were of two minds / because of the strife” (πάν- τες δὲ θεοὶ δίχα θυμὸν ἔθεντο / ἐξ ἔριδος, 94–95)—Zeus hastens the destruction of the Heroes: “And then he hastened to extinguish the great race of human * A version of this article was given at the Heartland Graduate Conference in Ancient Stud- ies at the University of Missouri in 2015. -

“100% Sanctification – Guaranteed” – Part 2 100% Sanctification

THE SECOND EPISTLE OF PETER TO THE CHURCH OF THE DISPERSION THROUGHOUT THE WORLD 2 PETER CHAPTER 1:5-9 MEDIA REFERENCE NUMBER SMX995 OCTOBER 27, 2019 THE TITLE OF THE MESSAGE: “100% Sanctification – Guaranteed” – Part 2 SUBJECT TOPICALLY REFERENCED UNDER: Faithfulness, Finishing, Church, Christianity, Discipleship 2 Peter 1:5-9 But also for this very reason, giving all diligence, add to your faith virtue, to virtue knowledge, 6 to knowledge self-control, to self-control perseverance, to perseverance godliness, 7 to godliness brotherly kindness, and to brotherly kindness love. 8 For if these things are yours and abound, you will be neither barren nor unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. 9 For he who lacks these things is shortsighted, even to blindness, and has forgotten that he was cleansed from his old sins. 100% Sanctification – Guaranteed! We have read throughout the Old Testament that God called His people to be set apart from this world and to be set apart for Him That Old Testament Requirement is Fulfilled in the New Testament Relationship And in Peter’s Day - The Early Church was Increasingly Thankful for that. It’s success / It’s effect / It’s influence / It’s earthly calling / From its heavenly position. 1 Thessalonians 5:23-24 Now may the God of peace Himself sanctify you completely; and may your whole spirit, soul, and body be preserved blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. 24 He who calls you is faithful, who also will do it. Reviewing Part 1 of Our Previous Teaching 100% Sanctification – Guaranteed! 1.) Means that we co-operate with God vs. -

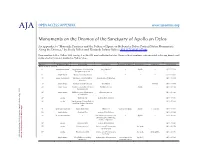

Supplemental Content: Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary Of

AJA OPEN ACCESS: APPENDIX www.ajaonline.org Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary of Apollo on Delos An appendix to “Honorific Practices and the Politics of Space on Hellenistic Delos: Portrait Statue Monuments Along the Dromos,” by Sheila Dillon and Elizabeth Palmer Baltes (AJA 117 [2013] 207–46). Base numbers follow Vallois 1923 (see fig. 3 in the AJA print-published article). Bases without numbers were recorded as having been found in the area but were not marked on Vallois’ plan. Base No. Monument Type Honorand(s) Dedicator(s) Reason(s) for Honor Dedicated to Sculptor(s) Reference(s) Bases set up ca. 250–200 5 equestrian statue Epigenes, son of Andron, the King Attalos I – Apollo – IG 11 4 1109 Pergamene general 8 single statue Donax, son of Apollonios – – – – IG 11 4 1202 16 group monument Aischylo(. .) and his father, Mennis, son of Nikarchos – – – IG 11 4 1168 Nikarchos 19 single statue female, Hellenistic queen? the Delians – – Thoinias IG 11 4 1088 20 single statue Autokles, son of Ainesidemos, Autokles, his son – Apollo – IG 11 4 1194 from Chalcidia 117.2) 25 single statue Phildemos, son of Pythermos Eumedes, his son – – – IG 11 4 1193 of Chalcedon 27 exedra family group demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1090 33 exedra family group of Jason, Eukleia, – – – – IG 11 4 1203 Timokleia, Straton, Timokleia, Sillis 41 victory monument Gallic dedication Attalos I(?) victory over Gauls Apollo (. .)epoiei IG 11 4 1110 50c single statue Aichmokritos demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1094 American Journal of Archaeology American 53 -

The Oracle and Cult of Ares in Asia Minor Matthew Gonzales

The Oracle and Cult of Ares in Asia Minor Matthew Gonzales ERODOTUS never fails to fascinate with his rich and detailed descriptions of the varied peoples and nations H mustered against Greece by Xerxes;1 but one of his most tantalizing details, a brief notice of the existence of an oracle of Ares somewhere in Asia Minor, has received little comment. This is somewhat understandable, as the name of the proprietary people or nation has disappeared in a textual lacuna, and while restoring the name of the lost tribe has ab- sorbed the energies of some commentators, no moderns have commented upon the remarkable and unexpected oracle of Ares itself. As we shall see, more recent epigraphic finds can now be adduced to show that this oracle, far from being the fantastic product of logioi andres, was merely one manifestation of Ares’ unusual cultic prominence in south/southwestern Asia Minor from “Homeric” times to Late Antiquity. Herodotus and the Solymoi […] 1 The so-called Catalogue of Forces preserved in 7.61–99. In light of W. K. Pritcéhesttp’s¤ dtahwo rodu¢g h» mreofbuota˝tnioanws eo‰xf osunc hs mscihkorlãarws, aksa O‹ .p rAorbmÒalyoru, wD . FehdlÊinog ,l aunkdio Se.r Wg°eastw, ßwkhaos steoekw teo‰x dei,s c§rped‹ idt ¢th teª asuit hkoerfitay loªf sHie krordãontuesa o n thixs ãanldk eoath:e pr rpÚowin dts¢, tIo w›silli skimrãplnye rseif eŒr ttãhe t ree kadae‹r kto° rPerait cphreotts’s∞ tnw ob omÚawj or trexatãmleknetas ,o f t§hpe∞irs waonr k,d S¢t udkieas i‹n AlnÒcifenot i:G reetkå Two podg¢ra phkyn IÆVm (aBwe rk=eãleky e1s9i8 2) 23f4–o2in85ik a°nodi sTih ek Laiatre Silch¤xoola otf oH. -

Stasis, Political Change and Political Subversion in Syracuse, 415-305 B.C

'STASIS', POLITICAL CHANGE Al']]) POLITICAL SUBVERSION IN SYRACUSE, 415-305 B.C. by DAVID JOHN BETTS, B.A.(Hons.) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA HOBART October 1980 To the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university, and contains no copy or paraphrase of material previously published or written by another person, except when due reference is made in the text of the thesis. Signed : (iii) CONTENTS Abstract iv Principal Ancient Texts vi Abbreviations, Textual Note vii INTRODUCTION : Scope and Intention of Thesis 1 CHAPTER 1 : Revolutionary Change and the Preservation of Constitutions CHAPTER 2 : The Nature and Method of Revolutionary Change and Political Subversion in Syracuse, 415-305 B.C. 45 CHAPTER 3 : Political Problems and the Role of the Leader in Syracuse, 415-305 B.C. 103 CHAPTER 4 : The Effect of Socio—Economic Conditions 151 CHAPTER 5 : Conclusion 180 APPENDIX : A Note on the Sources for Sicilian History 191 Footnotes 202 Tables 260 Maps 264 Bibliography 266 Addendum 271 (iv) ABSTRACT The thesis examines the phenomena of opr71-4,/5 , political change and political subversion in Syracuse from 415 to 305 B.C. The Introductory Chapter gives a general outline of the problems in this area, together with some discussion of the critical background. As the problems involved with the ancient sources for the period under discussion lie outside the mainstream of the thesis, these have been dealt with in the form of an appendix. -

Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES

Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES NUMBER 7 Editorial Board Chair: Donald Mastronarde Editorial Board: Alessandro Barchiesi, Todd Hickey, Emily Mackil, Richard Martin, Robert Morstein-Marx, J. Theodore Peña, Kim Shelton California Classical Studies publishes peer-reviewed long-form scholarship with online open access and print-on-demand availability. The primary aim of the series is to disseminate basic research (editing and analysis of primary materials both textual and physical), data-heavy re- search, and highly specialized research of the kind that is either hard to place with the leading publishers in Classics or extremely expensive for libraries and individuals when produced by a leading academic publisher. In addition to promoting archaeological publications, papyrolog- ical and epigraphic studies, technical textual studies, and the like, the series will also produce selected titles of a more general profile. The startup phase of this project (2013–2017) was supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Also in the series: Number 1: Leslie Kurke, The Traffic in Praise: Pindar and the Poetics of Social Economy, 2013 Number 2: Edward Courtney, A Commentary on the Satires of Juvenal, 2013 Number 3: Mark Griffith, Greek Satyr Play: Five Studies, 2015 Number 4: Mirjam Kotwick, Alexander of Aphrodisias and the Text of Aristotle’s Meta- physics, 2016 Number 5: Joey Williams, The Archaeology of Roman Surveillance in the Central Alentejo, Portugal, 2017 Number 6: Donald J. Mastronarde, Preliminary Studies on the Scholia to Euripides, 2017 Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity Olivier Dufault CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES Berkeley, California © 2019 by Olivier Dufault. -

Diodorus, the Ho and Xenophon: a Reassessment

chapter 4 Diodorus, the ho and Xenophon: A Reassessment This chapter presents a new reading of the relationship between Diodorus’ Bibliotheke, the ho (London papyrus, Florence papyrus and Cairo papyrus)1 and Xenophon’s Hellenica. Study cases are some accounts pertaining to the Spartan expedition against Persia in the early fourth century (the battle of Sardis,2 395bc) as well as episodes of the last phases of the Peloponnesian war (the battle of Notion, 407/406bc, Thrasyllus’ operations in the Aegean Sea, 409bc, the Thirty under Theramenes). The main objective is to cross-compare historiographical methods and prac- tices of the authors in question in order to revise and reject old-fashioned theories about Diodorus’ way of reworking his source material (in reference to some sections of books 13–15). All the cases examined contain very relevant information and have not hitherto been closely evaluated; the criterion cho- sen is thematic, not chronological, and a good deal of emphasis is placed on papyrological aspects and issues related to the three papyri forming the ho. Several crucial questions are raised here: in what way does Diodorus dis- tance himself from his sources, even when he follows them closely? How does he conciliate fourth-century history, Greek vocabulary and Roman his- toriographical modes and ideology? What functions do moralism and human chararacterisation have and how are they employed? 4.1 The ho as a Source for Diodorus’Bibliotheke Studying the ho requires us to turn our attention to Diodorean narrative, since we depend on it for much of what is known of mid-fourth-century history. -

Proceedings Ofthe Danish Institute at Athens IV

Proceedings ofthe Danish Institute at Athens IV Edited by Jonas Eiring and Jorgen Mejer © Copyright The Danish Institute at Athens, Athens 2004 The publication was sponsored by: The Danish Research Council for the Humanities Generalkonsul Gosta Enboms Fond. Proceedings of the Danish Institute at Athens General Editors: Jonas Eiring and Jorgen Mejer. Graphic design and production: George Geroulias, Press Line. Printed in Greece on permanent paper. ISBN: 87 7288 724 9 Distributed by: AARHUS UNIVERSITY PRESS Langelandsgade 177 DK-8200 Arhus N Fax (+45) 8942 5380 73 Lime Walk Headington, Oxford 0X3 7AD Fax (+44) 865 750 079 Box 511 Oakvill, Conn. 06779 Fax (+1)203 945 94 9468 Cover illustration: Finds from the Hellenistic grave at Chalkis, Aetolia. Photograph by Henrik Frost. The Platonic Corpus in Antiquity Jorgen Mejer Plato is the one and only philosopher particular edition which has determined from Antiquity whose writings have not only the Medieval tradition but also been preserved in their entirety. And our modern knowledge of Platonic dia not only have they been preserved, they logues, goes back to the Roman have been transmitted as a single col Emperor Tiberius' court-astrologer, lection of texts. Our Medieval manu Thrasyllus.2 Tarrant demonstrates rather scripts seem to go back to one particu convincingly that there is little basis for lar edition, an archetypus in two vol assuming that the tetralogical arrange umes, as appears from the subscript to ment existed before Thrasyllus, that it is the dialogue Menexenus, which is the possible to identify a philosophical posi last dialogue in the seventh tetralogy: tion which explains the tetralogies, that T8>iog toD JtQcbxou 6i6)dou. -

Status of Women in Ancient Greece

Center for Open Access in Science ▪ https://www.centerprode.com/ojas.html Open Journal for Anthropological Studies, 2019, 3(2), 49-54. ISSN (Online) 2560-5348 ▪ https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojas.0302.03049s _________________________________________________________________________ Status of Women in Ancient Greece Zhulduz Amangelidyevna Seitkasimova M. Auezov South Kazakhstan State University, KAZAKHSTAN Faculty of Pedagogy and Culture, Shymkent Received 18 October 2019 ▪ Revised 12 December 2019 ▪ Accepted 21 December 2019 Abstract This paper examines the status, position and roles of women in ancient Greece. Based on available historical sources, it can be clearly established that women in ancient Greece had an inferior position to men. They were primarily viewed as “species-extending beings”. In none of the Greek city-states did women have political rights and were not considered as citizens. The status of women in ancient Greece, in terms of role, position, opportunity etc., varied from one city-state to another. This status is well known for ancient Athens, based on the large number of historical sources that can document the basic characteristics of the status of women in ancient Athens. Keywords: women’ status, ancient Greece, society, family, gender discrimination. 1. Introduction What was the status and positions of women in ancient Greece, and what was the main characteristics of that status? Women in the ancient Greek world had no possess all rights as men possessed and had few rights in comparison to male citizens. The key restrictions that women had was that they could not vote in different public affairs, and also could not own or inherit land.