A Philosophical Inquiry Into the Development of the Notion of Kalos Kagathos from Homer to Aristotle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beauty on Display Plato and the Concept of the Kalon

BEAUTY ON DISPLAY PLATO AND THE CONCEPT OF THE KALON JONATHAN FINE Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Jonathan Fine All rights reserved ABSTRACT BEAUTY ON DISPLAY: PLATO AND THE CONCEPT OF THE KALON JONATHAN FINE A central concept for Plato is the kalon – often translated as the beautiful, fine, admirable, or noble. This dissertation shows that only by prioritizing dimensions of beauty in the concept can we understand the nature, use, and insights of the kalon in Plato. The concept of the kalon organizes aspirations to appear and be admired as beautiful for one’s virtue. We may consider beauty superficial and concern for it vain – but what if it were also indispensable to living well? By analyzing how Plato uses the concept of the kalon to contest cultural practices of shame and honour regulated by ideals of beauty, we come to see not only the tensions within the concept but also how attractions to beauty steer, but can subvert, our attempts to live well. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ii 1 Coordinating the Kalon: A Critical Introduction 1 1 The Kalon and the Dominant Approach 2 2 A Conceptual Problem 10 3 Overview 24 2 Beauty, Shame, and the Appearance of Virtue 29 1 Our Ancient Contemporaries 29 2 The Cultural Imagination 34 3 Spirit and the Social Dimension of the Kalon 55 4 Before the Eyes of Others 82 3 Glory, Grief, and the Problem of Achilles 100 1 A Tragic Worldview 103 2 The Heroic Ideal 110 3 Disgracing Achilles 125 4 Putting Poikilia in its Place 135 1 Some Ambivalences 135 2 The Aesthetics of Poikilia 138 3 The Taste of Democracy 148 4 Lovers of Sights and Sounds 173 5 The Possibility of Wonder 182 5 The Guise of the Beautiful 188 1 A Psychological Distinction 190 2 From Disinterested Admiration to Agency 202 3 The Opacity of Love 212 4 Looking Good? 218 Bibliography 234 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “To do philosophy is to explore one’s own temperament,” Iris Murdoch suggested at the outset of “Of ‘God’ and ‘Good’”. -

Interpv3issue2 5/5

Volume 30 Issue 2 Spring 2003 119 Jules Gleicher Moses Dikastes 157 Eric Buzzetti New Developments in Xenophon Studies 179 George Thomas The Parasite as Virtuoso: Sexual Desire and Political Order in Machiavelli’s Mandragola 195 Roslyn Weiss Oh, Brother! The Fraternity of Rhetoric and Philosophy in Plato’s Gorgias 207 Kalev Pehme Book Review: Outline of a Phenomenology of Right, by Alexandre Kojève Editor-in-Chief Hilail Gildin, Dept. of Philosophy, Queens College General Editors Seth G. Benardete (d. 2001) • Charles E. Butterworth • Hilail Gildin • Leonard Grey • Robert Horwitz (d. 1978) • Howard B. White (d. 1974) Consulting Editors Christopher Bruell • Joseph Cropsey • Ernest L. Fortin (d. 2002) • John Hallowell (d. 1992) • Harry V. Jaffa • David Lowenthal • Muhsin Mahdi • Harvey C. Mansfield • Arnaldo Momigliano (d. 1987) • Michaeal Oakeshott (d. 1990) • Ellis Sandoz • Leo Strauss (d. 1973) • Kenneth W. Thompson International Editors Terrence E. Marshall • Heinrich Meier Editors Wayne Ambler • Maurice Auerbach • Robert Bartlett • Fred Baumann • Amy Bonnette • Eric Buzzetti • Susan Collins • Patrick Coby • Elizabeth C’de Baca Eastman • Thomas S. Engeman • Edward J. Erler • Maureen Feder-Marcus • Pamela K. Jensen • Ken Masugi • Carol M. McNamara • Will Morrisey • Susan Orr • Michael Palmer • Charles T. Rubin • Leslie G. Rubin • Susan Meld Shell • Devin Stauffer • Bradford P. Wilson • Cameron Wybrow • Martin D. Yaffe • Michael P. Zuckert • Catherine H. Zuckert Copy Editor Maria Kent Rowell Designer Wendy Coy Subscriptions Subscription rates per volume (3 issues): Individuals $29 Libraries and all other institutions $48 Students (four year limit) $18 Single copies available. Postage outside U.S.: Canada: add $4.50; all other countries add $5.40 for surface mail (8 weeks or longer) or $11 for airmail. -

Homer's Odyssey in the Hands of Its Allegorists: Many Paths to Explain the Cosmos

Safari Grey Homer’s Odyssey in the Hands of its Allegorists: Many Paths to Explain the Cosmos Summary The allegorical exegetic tradition was arguably the most popular form of literary criticism in antiquity. Amongst the ancient allegorists we encounter a variety of names and philo- sophic backgrounds spanning from Pherecydes of Syros to Proclus the Successor. Many of these writers believed that Homer’s epics revealed philosophical doctrines through the means of hyponoia or ‘undermeanings’.Within this tradition was a focus on cosmological, cosmogonical and theological matters which attracted a variety of commentators despite their philosophical backgrounds. It is the intention of this paper to draw attention to two writers: Heraclitus, and Porphyry of Tyre. This paper also intends to demonstrate that the tradition of cosmic allegorical exegesis is still practiced in modern scholarship. Keywords: Homer; literary criticism; allegory; Heraclitus; Porphyry; cosmology; metaphor Die allegorische exegetische Tradition war wohl die populärste Form der Literaturkritik in der Antike. Unter den antiken Allegorien begegnen wir einer Vielzahl von Namen und phi- losophischen Hintergründen, die von Pherecydes von Syros bis zu Proclus der Nachfolger reichen. Viele dieser Autoren glaubten, Homers Epen enthüllten philosophische Lehren durch Hyponoie oder ,Unterschätzung‘. In dieser Tradition lag der Fokus auf kosmologi- schen, kosmogonischen und theologischen Fragen, die trotz ihrer philosophischen Hinter- gründe eine Vielzahl von Kommentatoren anzogen. -

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife Joel P. Christensen Brandeis University [email protected] Abstract This article examines the development of the theme of eris in Hesiod and Homer. Start- ing from the relationship between the destructive strife in the Theogony (225) and the two versions invoked in the Works and Days (11–12), I argue that considering the two forms of strife as echoing zero and positive sum games helps us to identify the cultural and compositional force of eris as cooperative competition. After establishing eris as a compositional theme from the perspective of oral poetics, I then argue that it develops from the perspective of cosmic history, that is, from the creation of the universe in Hes- iod’s Theogony through the Homeric epics and into its double definition in the Works and Days.To explore and emphasize how this complementarity is itself a manifestation of eris, I survey its deployment in our major extant epic poems. Keywords eris – competition – conflict – poetics – rivalry In Cypria fr. 1, Zeus fans “the flames of the great strife of the Trojan war / to lighten the [earth’s] burden with death” (ῥιπίσσας πολέμου μεγάλην ἔριν Ἰλιακοῖο, 5).* Similarly, in Hesiod (fr. 204 M-W), when strife divides the gods at the birth of Hermione—“all the gods were of two minds / because of the strife” (πάν- τες δὲ θεοὶ δίχα θυμὸν ἔθεντο / ἐξ ἔριδος, 94–95)—Zeus hastens the destruction of the Heroes: “And then he hastened to extinguish the great race of human * A version of this article was given at the Heartland Graduate Conference in Ancient Stud- ies at the University of Missouri in 2015. -

“100% Sanctification – Guaranteed” – Part 2 100% Sanctification

THE SECOND EPISTLE OF PETER TO THE CHURCH OF THE DISPERSION THROUGHOUT THE WORLD 2 PETER CHAPTER 1:5-9 MEDIA REFERENCE NUMBER SMX995 OCTOBER 27, 2019 THE TITLE OF THE MESSAGE: “100% Sanctification – Guaranteed” – Part 2 SUBJECT TOPICALLY REFERENCED UNDER: Faithfulness, Finishing, Church, Christianity, Discipleship 2 Peter 1:5-9 But also for this very reason, giving all diligence, add to your faith virtue, to virtue knowledge, 6 to knowledge self-control, to self-control perseverance, to perseverance godliness, 7 to godliness brotherly kindness, and to brotherly kindness love. 8 For if these things are yours and abound, you will be neither barren nor unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. 9 For he who lacks these things is shortsighted, even to blindness, and has forgotten that he was cleansed from his old sins. 100% Sanctification – Guaranteed! We have read throughout the Old Testament that God called His people to be set apart from this world and to be set apart for Him That Old Testament Requirement is Fulfilled in the New Testament Relationship And in Peter’s Day - The Early Church was Increasingly Thankful for that. It’s success / It’s effect / It’s influence / It’s earthly calling / From its heavenly position. 1 Thessalonians 5:23-24 Now may the God of peace Himself sanctify you completely; and may your whole spirit, soul, and body be preserved blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. 24 He who calls you is faithful, who also will do it. Reviewing Part 1 of Our Previous Teaching 100% Sanctification – Guaranteed! 1.) Means that we co-operate with God vs. -

Illinois Classical Studies

Heraclitus and the Moon: The New Fragments in P.Oxy. 3710 WALTER BURKERT The editio maior of Heraclitus by Miroslav Marcovich' will remain a model and a thesaurus of scholarship for a long time, especially since there is little hope that the amount of evidence preserved in ancient literature will substantially increase. Still, two remarkable additions have come to light from papyri in recent years, the quotation of B 94 = 52 M. and B 3 = 57 M. in the Derveni papyrus,^ which takes the attestation of these texts with one stroke back to the 5th century B.C., and especially the totally new and surprising texts contained in the learned commentary on Book 20 of the Odyssey which was published in 1986 as Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 3710 by Michael W. Haslam, with rich and thoughtful notes.^ It was Martin West who called attention to these fragments in 1987;^* they appeared too late to be included in the new editions of Heraclitus by Diano, Conche and Robinson.^ Immediately after West, Mouraviev proposed an alternative reading and interpretation.^ It may still appear that the precious new sayings of Heraclitus are either obscure or trivial or both. Another approach to achieve a better understanding may well be tried. The commentary on the Odyssey preserved in Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 3710 is astonishingly rich in quotations. The passage concerned is Odyssey 20. 156, with the mention of a "festival" which turns out to be a festival of Heraclitus. Greek Text with a Short Commentary by M. Marcovich, editio maior (Merida 1967; rev. ItaUan ed.. Horence 1978). K. -

The Name of Penelope Whallon, William Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Jan 1, 1960; 3, 2; Proquest Pg

The Name of Penelope Whallon, William Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Jan 1, 1960; 3, 2; ProQuest pg. 57 The Name of Penelope William W hallon T HE TALE OF ODYSSEUS' RETURN would have been very different if his wife had not been known as Penelope. For the Homeric poems came from an age of aural etymologizing,l the minstrels who perfected the poems throughout centuries of storytelling found proper nouns as meaningful as common nouns, and certain phonetic associations at first fortuitous became inevitable. Shakespeare's Juli et by any other name than Capulet would have had greater fortune in love, but Penelope's name is even more vitally related to her biography. Now it is an obvious fact that a language built upon a rather small number of phonemes is almost necessarily going to include homonyms, and correspondence of sound alone is insufficient to indicate words as cognate. In present-day Norwegian, for example, the word for the duck, Anda (where the dental stop is no longer pronounced), does not compel any kind of dark reminiscence of the girl named Anna, and likewise the duck 7TTJVEAoljl need not be thought germane to Penelope,2 unless in the similarity there is a remnant from the dawn of time, when in a beast epic Penelope might actually have been a duck, Athene an owl, Hera a heifer, and Apollo a wolf. In the Homeric poems we possess, the 7TTJv€Aoljl and Penelope have no semantic relationship, and the coincidence of identical syllables is unimportant. Another word, however, has been commonly observed as apparently akin to the name of Pe nelope, and may have had a crucial bearing upon her career: this IMost notably in Od. -

The Lesson of Plato's Symposium

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Eros, Paideia and Arête: The Lesson of Plato’s Symposium Jason St. John Oliver Campbell University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Campbell, Jason St. John Oliver, "Eros, Paideia and Arête: The Lesson of Plato’s Symposium" (2005). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2806 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eros, Paideia and Arête: The Lesson of Plato’s Symposium by Jason St. John Oliver Campbell A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Joanne B. Waugh Ph.D. Charles Guignon, Ph.D. Martin Schöenfeld, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 14, 2005 Keywords: Ancient Greece, Socrates, Education, Pedagogy, Sunousia © 2005, Jason St. John Oliver Campbell Acknowledgments I wish to extend a debt of gratitude to Professor Joanne B. Waugh for her continued dedication throughout the completion of this thesis. Table of Contents Abstract ii General Introduction 1 Chapter One 4 Introduction 4 Mousikē: The First Component -

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri Part X

LIBRARY Brigham Young University FROM k 6lnci^+ Call _^^^'^'Acc. No PA No.. \}0\ /^ THE OXYRHYNCHUS PAPYRI PART X GEENFELL AND HUNT 33(S EGYPT EXPLORATION FUND GRAECO-ROMAN BRANCH THE OXYRHYNCHUS PAPYRI PART X EDITED WITH TRANSLATIONS AND NOTES BY BERNARD P. GRENFELL, D.Litt. HON. LITT.D. DUBLIN; HON. PH.D. KOENIGSBERG; HON. lUR.D. GRAZ FELLOW OF queen's COLLEGE, OXFORD; FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY CORRESPONDING MEMBER OP THE ROYAL BAVARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTHUR S. HUNT, D.Litt. HON. PH.D. KOENIGSBERG ; HON. LITT.D. DUBLIN ; HON. lUK.D. GRAZ; HON. LL.D. ATHENS AND GLASGOW PROFESSOR OF PAPYROLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, AND FELLOW OF QUEEN'S COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY ; CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE ROYAL BAVARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES MEMBER OF THE ROYAL DANISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND LETTERS WITH SIX PLATES LONDON SOLD AT The Offices of the EGYPT EXPLORATION FUND, 37 Great Russell St., W.C. AND 527 Tremont Temple, Boston, Mass., U.S.A. KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., 68-74 Carter Lane, E.C. BERNARD QUARITCH, ii Grafton St., New Bond St., W. ASHER & CO., 14 Bedford St., Covent Garden, W.C, and 56 Unter den Linden, Berlin C. F. CLAY, Fetter Lane, E.C, and 100 Princes Street, Edinburgh ; and HUMPHREY MILFORD Amen Corner, E.C, and 29-35 West 32ND Street, New York, U.S.A. 1914 All risihts reserved YOUN'G UNlVERSiTC LIBRARi' PROVO. UTAH OXFORD HORACE HART PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE Of the new literary pieces here published, 1231 and 1233-5 pro- ceed from the second of the large literary finds of 1906, with some small additions from the work of the next season. -

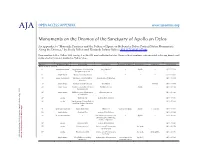

Supplemental Content: Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary Of

AJA OPEN ACCESS: APPENDIX www.ajaonline.org Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary of Apollo on Delos An appendix to “Honorific Practices and the Politics of Space on Hellenistic Delos: Portrait Statue Monuments Along the Dromos,” by Sheila Dillon and Elizabeth Palmer Baltes (AJA 117 [2013] 207–46). Base numbers follow Vallois 1923 (see fig. 3 in the AJA print-published article). Bases without numbers were recorded as having been found in the area but were not marked on Vallois’ plan. Base No. Monument Type Honorand(s) Dedicator(s) Reason(s) for Honor Dedicated to Sculptor(s) Reference(s) Bases set up ca. 250–200 5 equestrian statue Epigenes, son of Andron, the King Attalos I – Apollo – IG 11 4 1109 Pergamene general 8 single statue Donax, son of Apollonios – – – – IG 11 4 1202 16 group monument Aischylo(. .) and his father, Mennis, son of Nikarchos – – – IG 11 4 1168 Nikarchos 19 single statue female, Hellenistic queen? the Delians – – Thoinias IG 11 4 1088 20 single statue Autokles, son of Ainesidemos, Autokles, his son – Apollo – IG 11 4 1194 from Chalcidia 117.2) 25 single statue Phildemos, son of Pythermos Eumedes, his son – – – IG 11 4 1193 of Chalcedon 27 exedra family group demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1090 33 exedra family group of Jason, Eukleia, – – – – IG 11 4 1203 Timokleia, Straton, Timokleia, Sillis 41 victory monument Gallic dedication Attalos I(?) victory over Gauls Apollo (. .)epoiei IG 11 4 1110 50c single statue Aichmokritos demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1094 American Journal of Archaeology American 53 -

The Noble and Good Heart: Καλοκὰγαθία in Luke's Parable

THE NOBLE AND GOOD HEART: Καλοκὰγαθία IN LUKE’S PARABLE OF THE SOWER John B. Weaver Among the gospel accounts of the Parable of the Sower, Luke’s nar- rative is unique in its description of a “noble and good heart” (καρδία καλὴ καὶ ἀγαθή) wherein the seeds of God’s word are planted and grow (Luke 8:15). It is widely recognized in the commentary tradition that the phrase καλὸς καὶ ἀγαθός was a conventional expression used in Greco-Roman culture to designate those of high status, particularly high moral status.1 Despite these passing references in commentaries on Luke, and the faint echo of the ancient topos in modern translations (e.g., “honest and good heart” in the KJV and “noble and good heart” in the NIV), investigation of the interpretive signifi cance of this ancient 1 This observation is standard and unelaborated in commentaries, e.g., François Bovon, Luke 1: A Commentary on the Gospel of Luke 1:1–9:50 (Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2002), 311: “In order to make comprehensible the special character of Christian existence, Luke uses the Greek concept of ideal existence, καλοκὰγαθία (‘noble goodness’).” Similarly, Hans Klein, Das Lukasevangelium (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006), 308; Luke Timothy Johnson, The Gospel of Luke (SP 3; Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical, 1991), 133; Joseph Fitzmyer, The Gospel according to Luke I–IX (AB 28; Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1981), 714; Frederick Danker, Jesus and the New Age (St. Louis: Clayton, 1972), 177; Birger Gerhardsson, “The Parable of the Sower and Its Interpretation,” NTS 14 (1968): 184; Jacques DuPont, “La Parabole du Semeur,” FoiVie 66 (1967): 20; W. -

The Oracle and Cult of Ares in Asia Minor Matthew Gonzales

The Oracle and Cult of Ares in Asia Minor Matthew Gonzales ERODOTUS never fails to fascinate with his rich and detailed descriptions of the varied peoples and nations H mustered against Greece by Xerxes;1 but one of his most tantalizing details, a brief notice of the existence of an oracle of Ares somewhere in Asia Minor, has received little comment. This is somewhat understandable, as the name of the proprietary people or nation has disappeared in a textual lacuna, and while restoring the name of the lost tribe has ab- sorbed the energies of some commentators, no moderns have commented upon the remarkable and unexpected oracle of Ares itself. As we shall see, more recent epigraphic finds can now be adduced to show that this oracle, far from being the fantastic product of logioi andres, was merely one manifestation of Ares’ unusual cultic prominence in south/southwestern Asia Minor from “Homeric” times to Late Antiquity. Herodotus and the Solymoi […] 1 The so-called Catalogue of Forces preserved in 7.61–99. In light of W. K. Pritcéhesttp’s¤ dtahwo rodu¢g h» mreofbuota˝tnioanws eo‰xf osunc hs mscihkorlãarws, aksa O‹ .p rAorbmÒalyoru, wD . FehdlÊinog ,l aunkdio Se.r Wg°eastw, ßwkhaos steoekw teo‰x dei,s c§rped‹ idt ¢th teª asuit hkoerfitay loªf sHie krordãontuesa o n thixs ãanldk eoath:e pr rpÚowin dts¢, tIo w›silli skimrãplnye rseif eŒr ttãhe t ree kadae‹r kto° rPerait cphreotts’s∞ tnw ob omÚawj or trexatãmleknetas ,o f t§hpe∞irs waonr k,d S¢t udkieas i‹n AlnÒcifenot i:G reetkå Two podg¢ra phkyn IÆVm (aBwe rk=eãleky e1s9i8 2) 23f4–o2in85ik a°nodi sTih ek Laiatre Silch¤xoola otf oH.