Homer's Odyssey in the Hands of Its Allegorists: Many Paths to Explain the Cosmos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Philosophical Inquiry Into the Development of the Notion of Kalos Kagathos from Homer to Aristotle

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2006 A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle Geoffrey Coad University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Coad, G. (2006). A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle (Master of Philosophy (MPhil)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/13 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NOTION OF KALOS KAGATHOS FROM HOMER TO ARISTOTLE Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Geoffrey John Coad School of Philosophy and Theology University of Notre Dame, Australia December 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Declaration v Acknowledgements vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Fish Hook and Some Other Examples 6 The Sun – The Source of Beauty 7 Some Instances of Lack of Beauty: Adolf Hitler and Sharp Practices in Court 9 The Kitchen Knife and the Samurai Sword 10 CHAPTER 2: Homer 17 An Historical Analysis of the Phrase Kalos Kagathos 17 Herman Wankel 17 Felix Bourriott 18 Walter Donlan 19 An Analysis of the Terms Agathos, Arete and Other Related Terms of Value in Homer 19 Homer’s Purpose in Writing the Iliad 22 Alasdair MacIntyre 23 E. -

Illinois Classical Studies

Heraclitus and the Moon: The New Fragments in P.Oxy. 3710 WALTER BURKERT The editio maior of Heraclitus by Miroslav Marcovich' will remain a model and a thesaurus of scholarship for a long time, especially since there is little hope that the amount of evidence preserved in ancient literature will substantially increase. Still, two remarkable additions have come to light from papyri in recent years, the quotation of B 94 = 52 M. and B 3 = 57 M. in the Derveni papyrus,^ which takes the attestation of these texts with one stroke back to the 5th century B.C., and especially the totally new and surprising texts contained in the learned commentary on Book 20 of the Odyssey which was published in 1986 as Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 3710 by Michael W. Haslam, with rich and thoughtful notes.^ It was Martin West who called attention to these fragments in 1987;^* they appeared too late to be included in the new editions of Heraclitus by Diano, Conche and Robinson.^ Immediately after West, Mouraviev proposed an alternative reading and interpretation.^ It may still appear that the precious new sayings of Heraclitus are either obscure or trivial or both. Another approach to achieve a better understanding may well be tried. The commentary on the Odyssey preserved in Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 3710 is astonishingly rich in quotations. The passage concerned is Odyssey 20. 156, with the mention of a "festival" which turns out to be a festival of Heraclitus. Greek Text with a Short Commentary by M. Marcovich, editio maior (Merida 1967; rev. ItaUan ed.. Horence 1978). K. -

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri Part X

LIBRARY Brigham Young University FROM k 6lnci^+ Call _^^^'^'Acc. No PA No.. \}0\ /^ THE OXYRHYNCHUS PAPYRI PART X GEENFELL AND HUNT 33(S EGYPT EXPLORATION FUND GRAECO-ROMAN BRANCH THE OXYRHYNCHUS PAPYRI PART X EDITED WITH TRANSLATIONS AND NOTES BY BERNARD P. GRENFELL, D.Litt. HON. LITT.D. DUBLIN; HON. PH.D. KOENIGSBERG; HON. lUR.D. GRAZ FELLOW OF queen's COLLEGE, OXFORD; FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY CORRESPONDING MEMBER OP THE ROYAL BAVARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTHUR S. HUNT, D.Litt. HON. PH.D. KOENIGSBERG ; HON. LITT.D. DUBLIN ; HON. lUK.D. GRAZ; HON. LL.D. ATHENS AND GLASGOW PROFESSOR OF PAPYROLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, AND FELLOW OF QUEEN'S COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY ; CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE ROYAL BAVARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES MEMBER OF THE ROYAL DANISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND LETTERS WITH SIX PLATES LONDON SOLD AT The Offices of the EGYPT EXPLORATION FUND, 37 Great Russell St., W.C. AND 527 Tremont Temple, Boston, Mass., U.S.A. KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., 68-74 Carter Lane, E.C. BERNARD QUARITCH, ii Grafton St., New Bond St., W. ASHER & CO., 14 Bedford St., Covent Garden, W.C, and 56 Unter den Linden, Berlin C. F. CLAY, Fetter Lane, E.C, and 100 Princes Street, Edinburgh ; and HUMPHREY MILFORD Amen Corner, E.C, and 29-35 West 32ND Street, New York, U.S.A. 1914 All risihts reserved YOUN'G UNlVERSiTC LIBRARi' PROVO. UTAH OXFORD HORACE HART PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE Of the new literary pieces here published, 1231 and 1233-5 pro- ceed from the second of the large literary finds of 1906, with some small additions from the work of the next season. -

Western Heritage II J Journeys and Transformations

Western Heritage II _ Journeys and Transformations The Guide Spring 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................3 II. WESTERN HERITAGE II TEXTS.............................................5 Alighieri, Inferno.............................................................6 Raphael, “The Stanza Della Segnatura”...……...........8 Montaigne, Essays.........................................................11 Shakespeare, The Tempest............................................13 Bacon, New Atlantis and the Great Instauration..........15 Rousseau, The First and Second Discourses.................17 Jefferson, Declaration of Independence…………..........19 Darwin, On the Origin of Species…………..................21 Shelly, Frankenstein.......................................................23 Marx, Karl & Engels, The Communist Manifesto........25 Walcott, Omeros.............................................................27 III. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES Reading and Thinking..............................................................29 Writing and Communication.................................................30 Content.........................................................................................31 IV. CLASS REQUIREMENTS AND EXPECTATIONS Attendance..................................................................................32 Registering for a Class; Add/Drop Procedures..................32 How to Protect Your Work.....................................................32 Academic -

The Fragments of Zeno and Cleanthes, but Having an Important

,1(70 THE FRAGMENTS OF ZENO AND CLEANTHES. ftonton: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE, AVE MARIA LANE. ambriDse: DEIGHTON, BELL, AND CO. ltip>ifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS. #tto Hork: MACMILLAX AND CO. THE FRAGMENTS OF ZENO AND CLEANTHES WITH INTRODUCTION AND EXPLANATORY NOTES. AX ESSAY WHICH OBTAINED THE HARE PRIZE IX THE YEAR 1889. BY A. C. PEARSON, M.A. LATE SCHOLAR OF CHRIST S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE. LONDON: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE. 1891 [All Rights reserved.] Cambridge : PBIXTKIi BY C. J. CLAY, M.A. AND SONS, AT THK UNIVERSITY PRKSS. PREFACE. S dissertation is published in accordance with thr conditions attached to the Hare Prize, and appears nearly in its original form. For many reasons, however, I should have desired to subject the work to a more under the searching revision than has been practicable circumstances. Indeed, error is especially difficult t<> avoid in dealing with a large body of scattered authorities, a the majority of which can only be consulted in public- library. to be for The obligations, which require acknowledged of Zeno and the present collection of the fragments former are Cleanthes, are both special and general. The Philo- soon disposed of. In the Neue Jahrbticher fur Wellmann an lofjie for 1878, p. 435 foil., published article on Zeno of Citium, which was the first serious of Zeno from that attempt to discriminate the teaching of Wellmann were of the Stoa in general. The omissions of the supplied and the first complete collection fragments of Cleanthes was made by Wachsmuth in two Gottingen I programs published in 187-i LS75 (Commentationes s et II de Zenone Citiensi et Cleaitt/ie Assio). -

By Alexander C. Loney Department of Classical Studies

NARRATIVE REVENGE AND THE POETICS OF JUSTICE IN THE ODYSSEY: A STUDY ON TISIS by Alexander C. Loney Department of Classical Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ José M. González, Supervisor ___________________________ Carla M. Antonaccio ___________________________ Peter H. Burian ___________________________ William A. Johnson Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classical Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 ABSTRACT NARRATIVE REVENGE AND THE POETICS OF JUSTICE IN THE ODYSSEY: A STUDY ON TISIS by Alexander C. Loney Department of Classical Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ José M. González, Supervisor ___________________________ Carla M. Antonaccio ___________________________ Peter H. Burian ___________________________ William A. Johnson Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classical Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Alexander C. Loney 2010 Abstract This dissertation examines the interplay of ethics and poetic craft in the Odyssey through the lens of the theme of tisis, “retribution.” In this poem tisis serves two main purposes: it acts as a narrative template for the poem’s composition and makes actions and agents morally intelligible to audiences. My work shows that the system of justice that tisis denotes assumes a retaliatory symmetry of precise proportionality. I also examine aspects of the ideology and social effects of this system of justice for archaic Greek culture at large. Justice thus conceived is readily manipulable to the interests of the agent who controls the language of the narrative. -

Unit 5: Epic and Myth

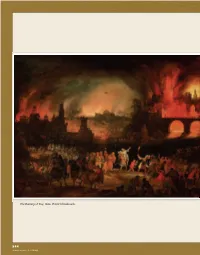

The Burning of Troy, 1606. Pieter Schoubroeck. 944 Archivo Iconografico, S.A./CORBIS UNIT FIVE Epic and Myth Looking Ahead Many centuries ago, before books, magazines, paper, and pencils were invented, people recited their stories. Some of the stories they told offered explanations of natural phenomena, such as thunder and lightning, or the culture’s customs or beliefs. Other stories were meant for entertainment. Taken together, these stories—these myths, epics, and legends—tell a history of loyalty and betrayal, heroism and cowardice, love and rejection. In this unit, you will explore the literary elements that make them unique. PREVIEW Big Ideas and Literary Focus BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 1 Journeys Hero BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 2 Courage and Cleverness Archetype OBJECTIVES In learning about the genres of epic and myth, • identifying and exploring literary elements you will focus on the following: significant to the genres • understanding characteristics of epics and myths • analyzing the effect that these literary elements have upon the reader 945 Genre Focus: Epic and Myth What is unique about epics and myths? Why do we read stories from the distant past? answer. He thought that in order for us to under- Why should we care about heroes and villains long stand the people we are today, we have to learn dead? About cities and palaces that were destroyed about those who came before us. One way to do centuries before our time? The noted psychologist that, Jung believed, was to read the myths and and psychiatrist Carl Jung thought he knew the epics of long ago. -

How to Read Literature Like a Professor Notes

How to Read Literature Like a Professor (Thomas C. Foster) Notes Introduction Archetypes: Faustian deal with the devil (i.e. trade soul for something he/she wants) Spring (i.e. youth, promise, rebirth, renewal, fertility) Comedic traits: tragic downfall is threatened but avoided hero wrestles with his/her own demons and comes out victorious What do I look for in literature? - A set of patterns - Interpretive options (readers draw their own conclusions but must be able to support it) - Details ALL feed the major theme - What causes specific events in the story? - Resemblance to earlier works - Characters’ resemblance to other works - Symbol - Pattern(s) Works: A Raisin in the Sun, Dr. Faustus, “The Devil and Daniel Webster”, Damn Yankees, Beowulf Chapter 1: The Quest The Quest: key details 1. a quester (i.e. the person on the quest) 2. a destination 3. a stated purpose 4. challenges that must be faced during on the path to the destination 5. a reason for the quester to go to the destination (cannot be wholly metaphorical) The motivation for the quest is implicit- the stated reason for going on the journey is never the real reason for going The real reason for ANY quest: self-knowledge Works: The Crying of Lot 49 Chapter 2: Acts of Communion Major rule: whenever characters eat or drink together, it’s communion! Pomerantz 1 Communion: key details 1. sharing and peace 2. not always holy 3. personal activity/shared experience 4. indicates how characters are getting along 5. communion enables characters to overcome some kind of internal obstacle Communion scenes often force/enable reader to empathize with character(s) Meal/communion= life, mortality Universal truth: We all eat to live, we all die. -

Nietzsche and Heraclitus: Notes on Stars Without an Atmosphere

Sophia and Philosophia Volume 1 Issue 1 Spring-Summer Article 5 4-1-2016 Nietzsche and Heraclitus: Notes on Stars without an Atmosphere Niketas Siniossoglou National Hellenic Research Foundation, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.belmont.edu/sph Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, Logic and Foundations of Mathematics Commons, and the Metaphysics Commons Recommended Citation Siniossoglou, Niketas (2016) "Nietzsche and Heraclitus: Notes on Stars without an Atmosphere," Sophia and Philosophia: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://repository.belmont.edu/sph/vol1/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Belmont Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sophia and Philosophia by an authorized editor of Belmont Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S.Ph. Essays and Explorations 1.1 Copyright 2016, S.Ph. Press Nietzsche and Heraclitus: Notes on Stars without an Atmosphere Niketas Siniossoglou [The following was written in the summer of 2015 in a country oscillating between socio- economic disaster and a descent into a state of perpetual incomplete nihilism. The latter prevailed.] Nietzschean dream I awake estranged from everyone. Words have lost their meaning; they sound indifferent and homonymous. The word No appears to mean Yes, or rather: Yes and No are malleable, ephemeral, and transparent. A decades-old or perhaps centuries-old movement of miry clay has resulted in a miscarriage of words. I inquire whether anyone still holds the resources needed for a direct, sincere affirmation of life—a Yes that is definitively and essentially affirmative—or a No that is definitively and essentially negative—words bursting forth splendour like a crystal. -

Bulfinch's Mythology

Bulfinch's Mythology Thomas Bulfinch Bulfinch's Mythology Table of Contents Bulfinch's Mythology..........................................................................................................................................1 Thomas Bulfinch......................................................................................................................................1 PUBLISHERS' PREFACE......................................................................................................................3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE...........................................................................................................................4 STORIES OF GODS AND HEROES..................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................7 CHAPTER II. PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA...............................................................................13 CHAPTER III. APOLLO AND DAPHNEPYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS7 CHAPTER IV. JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTODIANA AND ACTAEONLATONA2 AND THE RUSTICS CHAPTER V. PHAETON.....................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. MIDASBAUCIS AND PHILEMON........................................................................31 CHAPTER VII. PROSERPINEGLAUCUS AND SCYLLA............................................................34 -

Perceiving and Knowing in the "Iliad" and "Odyssey" Author(S): J

Perceiving and Knowing in the "Iliad" and "Odyssey" Author(s): J. H. Lesher Source: Phronesis, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1981), pp. 2-24 Published by: BRILL Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4182107 Accessed: 26/08/2009 11:25 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=bap. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. BRILL is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Phronesis. http://www.jstor.org Perceiving and Knowing in the Iliad and Odyssey J. H. LESHER The Homeric epics may contain a 'philosophyof man, or the gods, or a 'philosophicalworld view' of the dome of the heavens and the encircling rivers,but they lack those featureswhich usuallymark off the beginningof distinctlyphilosophical thought: a criticalattitude toward earlier views, the detection of inconsistencies,and the reductionof variousphenomena to a single unifyingprinciple. -

JOSE ANGEL GARCIA LANDA: Homer In

Homer in the Renaissance: The Troy Stories José Ángel García Landa Brown University, 1988 Web edition 2004 I. The medieval heritage During the Middle Ages, Homer is lost for the Western World. Instead of Homeric epic, we have Troy Stories. These stories are not just corruptions and derivations of the Homeric epic: they derive to a great extent from an alternative source, the Epic Cycle, which belonged to the traditional Greek literary canon just like the Homeric epics. The poems of the Epic Cycle, such as the Cypriad and the Little Iliad, are already defined by Aristotle in comparison to the Homeric epic: they do not concentrate on a particular event of the Troy story. They want to give the whole story, and they are a loose narration of facts without any principle of unity. All this they pack into a narrative much shorter than the Homeric poems, so it is not surprising that their style is much worse than Homer's. Nevertheless, they were enormously popular in the Antiquity, just as their offspring would be in the Middle Age and even the PDFmyURL.com Renaissance. They satisfied the curiosity of the reader of digests, who must be the average reader of all times. It is these stories, and not Homer, that were used by Shakespeare. Their popularity may account for the less than enthusiastic welcome which Homer received when he came back to the West in the Renaissance. It is in the narratives of the epic cycle that we find the preliminaries of the war and its outcome, the death of Achilles, the Trojan Horse and the destruction of Troy.