1.1 Visa Work: a Two Step Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution: Electronically Initiated By: ANM-300 CHANGE U.S

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION ORDER CHANGE NM 3930.11 FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 6 Effective Date: National Policy 09/12/17 SUBJ: Aviation Medical Examiner for FAA Employees and Applicants Requiring Medical Certification. 1. Purpose. This order transmits Aviation Medical Examiner – Employee Examiner (AME- EE) information to the following: Transport Airplane Directorate (ANM-120s, ANM-130s, ANM-140s, ANM-150s), Flight Standards (FSDOs, Alaska CMO, SWA-CMO, Seattle AEG) and the ATO Western Service Area with Enroute and Terminal employees assigned to facilities located in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming requiring Federal Aviation Administration Aerospace Medical Certification. 2. Who this change affects. Branch level and above in the following divisions in the Northwest Mountain Region: Aerospace Medicine, Flight Standards, Transport Airplane Directorate and the ATO Western Service Area (CO, ID, MT, OR, UT, WA and WY) - Enroute and Terminal. 3. Disposition of Transmittal Paragraph. Retain this transmittal sheet until the directive is cancelled by a new directive. PAGE CHANGE CONTROL CHART Remove Pages Dated Insert Pages Dated Appendix A 9/1/17 Appendix A 9/12/17 4. 5. Administrative Information. This order change is distributed to Branch level and above in the following divisions in the Northwest Mountain Region: Aerospace Medicine, Flight Standards, Transport Airplane Directorate and the ATO Western Service Area (CO, ID, MT, OR, UT, WA and WY) - Enroute and Terminal. Responsibility for Distribution: The above divisions are responsible for verifying that there have been no updates to this order prior to scheduling an employee exam. Brett A. Wyrick, D.O. Regional Flight Surgeon Northwest Mountain Region Distribution: Electronically Initiated By: ANM-300 U.S. -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Clarification of Nonimmigrant Visa Status

WGIUPD GENERAL INFORMATION SYSTEM 02/10/04 DIVISION: Office of Medicaid Management PAGE 1 GIS 04 MA/002 TO: Local District Commissioners, Medicaid Directors FROM: Kathryn Kuhmerker, Deputy Commissioner Office of Medicaid Management SUBJECT: Clarification of Nonimmigrant Visa Status EFFECTIVE DATE: Immediately CONTACT PERSON: Local District Support Unit Upstate (518) 474-8216 NYC (212) 268-6855 The purpose of this GIS message is to clarify nonimmigrant visa status. This GIS message supersedes GIS 03 MA/005 issued 02/24/03. As explained below, nonimmigrants who hold a K, S, U or V visa are to be considered as “permanently residing in the United States under color of law” (PRUCOL) and, if otherwise eligible, may receive Medicaid, Family Health Plus (FHPlus) and Child Health Plus A (CHPlus A). However, holders of other nonimmigrant visas that are issued to persons in the United States on a temporary basis only are eligible for Medicaid only for the treatment of an emergency medical condition. There have been several new visa categories issued by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) [formerly the Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) and the Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services (BCIS)] over the past several years. Some categories of nonimmigrant status allow the status (visa) holder to work and eventually adjust to Lawful Permanent Residence (LPR). These categories allow the individual to apply for adjustment to LPR status after he or she has had the nonimmigrant status for a period of time. Such statuses include, for example: K status: For the spouse, child, or fiancé (e) of a U.S. -

Logic and Sets Clast Mathematics Competencies

5 LOGIC AND SETS CLAST MATHEMATICS COMPETENCIES IE1: Deduce facts of set inclusion or set non-inclusion from a diagram IIE1: Identify statements equivalent to the negations of simple and compound statements IIE2: Determine equivalence or non-equivalence of statements IIE3: Draw logical conclusions from data IIE4: Recognize that an argument may not be valid even though its conclusion is true IIIE1: Recognize valid reasoning patterns as illustrated by valid arguments in everyday language IIIE2: Select applicable rules for transforming statements without affecting their meaning IVE1: Draw logical conclusions when facts warrant them 226 5.1 EQUIVALENT STATEMENTS The word logic is derived from the Greek word logos which may be interpreted to mean reason or discourse. Most of the study of logic revolves around the idea of a statement which we shall discuss next. T TERMINOLOGY -- STATEMENTS DEFINITION OF A STATEMENT EXAMPLES A statement is a declarative sentence which I will study today. can be classified as true or false. 2 is an even number. CONJUNCTIONS (p and q) Let e represent the statement "2 is an even If two statements are connected by the word Let w represent the statement "and" (or an equivalent word such as "but"), "2 is a whole number". The statement: the resulting statement is called a conjunction "2 is an even number and 2 is a whole and is denoted by p ∧ q. number" is a conjunction which can be written The CLAST simply uses the notation p and q. as "e ∧ w" or as "e and w". DISJUNCTIONS (p or q) Let h be: I will study hard If two statements are connected by the word and f be: I will fail the test "or" (or an equivalent word), the resulting The statement "I will study hard or I will fail statement is called a disjunction and is denoted the test" is a disjunction which can be written by p ∨ q. -

Kin Relationships

In H. T. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships (pp. 951-954). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Kin Relationships Kin relationships are traditionally defined as ties based on blood and marriage. They include lineal generational bonds (children, parents, grandparents, and great- grandparents), collateral bonds (siblings, cousins, nieces and nephews, and aunts and uncles), and ties with in-laws. An often-made distinction is that between primary kin (members of the families of origin and procreation) and secondary kin (other family members). The former are what people generally refer to as “immediate family,” and the latter are generally labeled “extended family.” Marriage, as a principle of kinship, differs from blood in that it can be terminated. Given the potential for marital break-up, blood is recognized as the more important principle of kinship. This entry questions the appropriateness of traditional definitions of kinship for “new” family forms, describes distinctive features of kin relationships, and explores varying perspectives on the functions of kin relationships. Questions About Definition Changes over the last thirty years in patterns of family formation and dissolution have given rise to questions about the definition of kin relationships. Guises of kinship have emerged to which the criteria of blood and marriage do not apply. Assisted reproduction is a first example. Births resulting from infertility treatments such as gestational surrogacy and in vitro fertilization with ovum donation challenge the biogenetic basis for kinship. A similar question arises for adoption, which has a history 2 going back to antiquity. Partnerships formed outside of marriage are a second example. Strictly speaking, the family ties of nonmarried cohabitees do not fall into the category of kin, notwithstanding the greater acceptance over time of consensual unions both formally and informally. -

Fraud Risk Management: a Guide to Good Practice

Fraud risk management A guide to good practice Acknowledgements This guide is based on the fi rst edition of Fraud Risk Management: A Guide to Good Practice. The fi rst edition was prepared by a Fraud and Risk Management Working Group, which was established to look at ways of helping management accountants to be more effective in countering fraud and managing risk in their organisations. This second edition of Fraud Risk Management: A Guide to Good Practice has been updated by Helenne Doody, a specialist within CIMA Innovation and Development. Helenne specialises in Fraud Risk Management, having worked in related fi elds for the past nine years, both in the UK and other countries. Helenne also has a graduate certifi cate in Fraud Investigation through La Trobe University in Australia and a graduate certifi cate in Fraud Management through the University of Teeside in the UK. For their contributions in updating the guide to produce this second edition, CIMA would like to thank: Martin Birch FCMA, MBA Director – Finance and Information Management, Christian Aid. Roy Katzenberg Chief Financial Offi cer, RITC Syndicate Management Limited. Judy Finn Senior Lecturer, Southampton Solent University. Dr Stephen Hill E-crime and Fraud Manager, Chantrey Vellacott DFK. Richard Sharp BSc, FCMA, MBA Assistant Finance Director (Governance), Kingston Hospital NHS Trust. Allan McDonagh Managing Director, Hibis Europe Ltd. Martin Robinson and Mia Campbell on behalf of the Fraud Advisory Panel. CIMA would like also to thank those who contributed to the fi rst edition of the guide. About CIMA CIMA, the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants, is the only international accountancy body with a key focus on business. -

8Th Grade Text Structure Lesson, Practice, and Answer Key (Study Island) 1

8th Grade Text Structure Lesson, Practice, and Answer Key (Study Island) 1 Text Structure When you understand how the writer has organized information, you will understand and remember the text better. Writers organize text in several different ways. Cause/Effect The text shows that one event causes another thing to happen. Look for words like "because," "then," "since," and "as a result." Example: It rained for the first few days of the camping trip. As a result, most of the campers were restless and wanted to go home. Comparison/Contrast The text shows how ideas or things are alike or different. Look for words like "best," "more," "better," "less," "worse," "easier," and "than." Example: The best time to visit the Rocky Mountains is early fall. The weather is cooler in the fall than in the summer. You will see fewer people and more animals. The fall colors are more beautiful. Description When you want to paint a picture with words, use description to organize your ideas. To make the picture come alive in your reader's mind, use a lot of adjectives and describe what you would see, taste, smell, feel, or hear. Adjectives are words like "pretty," "sweet," "smooth," and "loud." Example: The cellar was cold, damp, and dark. It smelled musty and old. Problem/Solution The text is split into two parts: One part presents a problem, and the other part gives the solution to the problem. Look for words like "problem," "solution," "solve," and "plan." Example: The city of Taylor has fifteen public swimming pools. In the past, plenty of lifeguards have been available for staffing the pools throughout the summer. -

Intel® She Will Connect: Connecting Women in Africa to Opportunity

WOMEN AND THE WEB Bridging the Internet Gender Gap* BILLION Regional Internet Access Women’s Internet Access INTEL®USERS SHE WILL CONNECT 2.4ConnectingWORLDWIDE women in Africa to opportunity through technology. 79% 64% 28% 40% The Women and the WebEgypt 32% report16% outlined nearly 25 percent fewer women than men are online in emerging markets. In Sub-Saharan Africa that number rises to 45 percent. In response to the report’s findings, Intel and Mexico 34% 43% its partners committed to reducing the InternetIndia 8% gender gap by helping to put the Internet within the grasp of women in Africa. Women and girls willUganda 9% benefit from the information, knowledge, and connections available on the web and through information and communication technologies (ICTs). We are striving to enable the social IN ASIA andINTERNET economic ACCESS empowerment of women through access to opportunities, educational, financial, health and IN NORTH AMERICA 8% genderIS NEARLY specificTHA Tinformation, OF 28% e-governmentOF WOMEN services, and national and global news. Our goal is to reach 5 million AFRICA OF THE POPULATION IN INDIA HAVE women5X in the region byHAS the INTERNET end AC CESSof 2020.INTERNET ACCESS DEVELOPING COUNTRIES AND THE INTERNET GENDER GAP Women in developing countries frequently lack access to the Internet. Why Women? Women in developing countries are nearly 600 25% less likely to be online than men. 800 MILLION MILLION Women perform 60 percent of the world’s work, produce 50 percent of the food—but earn 10 percent of the income, and own 1 percent of the 43% 10% assets. -

Dna by the Entirety

DNA BY THE ENTIRETY Natalie Ram The law fails to accommodate the inconvenient fact that an individual’s identifiable genetic information is involuntarily and immutably shared with her close genetic relatives. Legal institutions have established that individuals have a cognizable interest in control- ling genetic information that is identifying to them. The Supreme Court recognized in Maryland v. King that the Fourth Amendment is impli- cated when arrestees’ DNA is analyzed, and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act protects individuals from genetic discrimination in the employment and health-insurance markets. But genetic infor- mation is not like other forms of private or personal information because it is shared—immutably and involuntarily—in ways that are identifying of both the source and that person’s close genetic relatives. Standard approaches to addressing interests in genetic information have largely failed to recognize this characteristic, treating such infor- mation as individualistic. While many legal frames may be brought to bear on this problem, this Article focuses on the law of property. Specifically, looking to the law of tenancy by the entirety, this Article proposes one possible frame- work for grappling with the overlapping interests implicated in genetic identification and analysis. Tenancy by the entirety, like interests in shared identifiable genetic information, calls for the difficult task of conceptualizing two persons as one. The law of tenancy by the entirety thus provides a useful analytical framework for considering how legal institutions might take interests in shared identifiable genetic infor- mation into account. This Article examines how this framework may shape policy approaches in three domains: forensic identification, genetic research, and personal genetic testing. -

Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 104 | Issue 3 Article 4 2016 Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law Shelly Kreiczer-Levy College of Law and Business in Ramat Gan Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Family Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Laufer-Ukeles, Pamela and Kreiczer-Levy, Shelly (2016) "Family Formation and the Home," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 104 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol104/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles' & Shelly Kreiczer-Levj INTRODUCTION' In this article, we consider the relevance of home sharing in family formation. When couples or groups of persons are recognized as families, they are afforded significant benefits and given certain obligations by the law.4 Families have their own category of laws, rights, and obligations.' Currently, the law of family formation and recognition is in a state of flux. Although in some respects the defining legal lines of the family have been well settled for centuries around blood and the formal legal ties of marriage and parenthood, in significant ways, the family form has been fundamentally altered over the past few decades. -

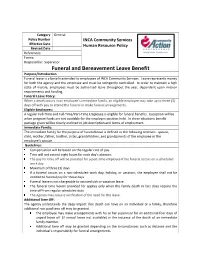

Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral Leave Is a Benefit Extended to Employees of INCA Community Services

Category General Policy Number INCA Community Services Effective Date Human Resource Policy Revised Date References: Forms: Responsible: Supervisor Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral leave is a benefit extended to employees of INCA Community Services. Leave represents money for both the agency and the employee and must be stringently controlled. In order to maintain a high state of morale, employees must be authorized leave throughout the year, dependent upon mission requirements and funding. Funeral Leave Policy: When a death occurs in an employee’s immediate family, an eligible employee may take up to three (3) days off with pay to attend the funeral or make funeral arrangements. Eligible Employees: A regular Full-Time and Full-Time/Part-Time Employee is eligible for funeral benefits. Exception will be when program funds are not available for the employee position held. In these situations benefit package given will be clearly outlined in job description and terms of employment. Immediate Family: The immediate family for the purpose of funeral leave is defined as the following relatives: spouse, child, mother, father, brother, sister, grandchildren, and grandparents of the employee or the employee’s spouse. Guidelines: Compensation will be based on the regular rate of pay. Time will not exceed eight hours for each day’s absence. The pay for time off will be prorated for a part-time employee if the funeral occurs on a scheduled work day. Maximum of three (3) days. If a funeral occurs on a non-scheduled work day, holiday, or vacation, the employee shall not be entitled to funeral pay for those days. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.