Towards Further Understanding of the Indus Script*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium of the National Academy Of

1 Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium of the National Academy of Sciences Early Cities: New Perspectives on Pre-Industrial Urbanism Final Revisions: Oct. 1, 2005 Indus Urbanism: New Perspectives on its Origin and Character Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin, Madison During the past two decades a variety of archaeological research projects focused on the Indus civilization have made it possible to refine earlier models regarding the origin and character of this distinctive urban society. Excavations at the major city of Harappa have revealed a long developmental sequence from its origins to its eventual decline and subsequent transformation. Recent excavations at the large urban centers of Dholavira and Rakhigarhi, along with reexamination of the largest city of Mohenjo-daro have shown that the development of urbanism was not uniform throughout the greater Indus region (Kenoyer 1998). Detailed studies within each city have revealed many shared characteristics as well as some unique features relating to the dynamic process of city growth and decline. In addition to the excavations of larger urban centers, regional surveys and extensive excavations at smaller settlements have provided a new perspective on the nature of interaction between large and small urban centers and even rural settlements. The increase in radiocarbon dates from well-documented contexts in stratigraphic excavations has helped to refine the chronology of settlements in both core areas and rural areas (Meadow and Kenoyer 2005b; Possehl 2002a; Possehl 2002c). On the basis of a more refined chronology and comparisons of the material culture, it appears that some rural settlements may have been directly linked to the major cities, while others appear to have had relatively little direct contact during some time periods (Meadow and Kenoyer 2005b). -

5. the Harappan Script Controversy

5. The Harappan script controversy (Subchapters 5.1-10 are the text of the paper “The Vedic Harappans in writing: Remarks in expectation of a decipherment of the Indus script”, written in late 1999, if I remember correctly. Instead of a postscript, subchapters 5.11-12 summarize a later development in 2003-2004, which throws an entirely different light on the meaning of the Indus script. At the time of editing this collection, I am agnostic on this question.) 5.1. Introduction In the Harappan cities some 4200 seals, many of them duplicates, have been found which carry short inscriptions in an otherwise unknown script. There is not the slightest doubt that this harvest of Harappan writings is but the tip of an iceberg, in this sense that the Harappan culture must have produced much more copious writings, but that most of them disappeared because the writing materials were not resistant to the ravages of time, particularly in the Indian climate. This fatality can still be seen today, when the libraries of many impoverished maharajas' castles are full of manuscripts which are decaying under our very eyes, turning large chunks of India's national memory and heritage into dust. Even of the oldest and most popular texts, the extant manuscripts are seldom older than a few centuries, copies made as the only guarantee to save the texts from the ravages of time which were destroying the earlier copies. It is fair to assume that a text corpus proportionate in size to the enormous extent of the Harappan cultural space, has gone the same way into oblivion. -

Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Signmaking, Chino-Latino Style: Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes _______________________________________________ DAVID A. COLÓN TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Concrete poetry—the aesthetic instigated by the vanguard Noigandres group of São Paulo, in the 1950s—is a hybrid form, as its elements derive from opposite ends of visual comprehension’s spectrum of complexity: literature and design. Using Dick Higgins’s terminology, Claus Clüver concludes that “concrete poetry has taken the same path toward ‘intermedia’ as all the other arts, responding to and simultaneously shaping a contemporary sensibility that has come to thrive on the interplay of various sign systems” (Clüver 42). Clüver is considering concrete poetry in an expanded field, in which the “intertext” poems of the 1970s and 80s include photos, found images, and other non-verbal ephemera in the Concretist gestalt, but even in limiting Clüver’s statement to early concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s, the idea of “the interplay of various sign systems” is still completely appropriate. In the Concretist aesthetic, the predominant interplay of systems is between literature and design, or, put another way, between words and images. Richard Kostelanetz, in the introduction to his anthology Imaged Words & Worded Images (1970), argues that concrete poetry is a term that intends “to identify artifacts that are neither word nor image alone but somewhere or something in between” (n/p). Kostelanetz’s point is that the hybridity of concrete poetry is deep, if not unmitigated. Wendy Steiner has put it a different way, claiming that concrete poetry “is the purest manifestation of the ut pictura poesis program that I know” (Steiner 531). -

ICONS and SIGNS from the ANCIENT HARAPPA Amelia Sparavigna ∗ Dipartimento Di Fisica, Politecnico Di Torino C.So Duca Degli Abruzzi 24, Torino, Italy

ICONS AND SIGNS FROM THE ANCIENT HARAPPA Amelia Sparavigna ∗ Dipartimento di Fisica, Politecnico di Torino C.so Duca degli Abruzzi 24, Torino, Italy Abstract Written words probably developed independently at least in three places: Egypt, Mesopotamia and Harappa. In these densely populated areas, signs, icons and symbols were eventually used to create a writing system. It is interesting to see how sometimes remote populations are using the same icons and symbols. Here, we discuss examples and some results obtained by researchers investigating the signs of Harappan civilization. 1. Introduction The debate about where and when the written words were originated is still open. Probably, writing systems developed independently in at least three places, Egypt, Mesopotamia and Harappa. In places where an agricultural civilization flourished, the passage from the use of symbols to a true writing system was early accomplished. It means that, at certain period in some densely populated area, signs and symbols were eventually used to create a writing system, the more complex society requiring an increase in recording and communication media. Signs, symbols and icons were always used by human beings, when they started carving wood or cutting stones and painting caves. We find signs on drums, textiles and pottery, and on the body itself, with tattooing. To figure what symbols used the human population when it was mainly composed by small groups of hunter-gatherers, we could analyse the signs of Native Americans. Our intuition is able to understand many of these old signs, because they immediately represent the shapes of objects and animals. It is then quite natural that signs and icons, born among people in a certain region, turn out to be used by other remote populations. -

Introduction Roger D

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-56256-0 — The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages Edited by Roger D. Woodard Excerpt More Information chapter 1 Introduction roger d. woodard 1.1 Preliminary remarks What makes a language ancient? The term conjures up images, often romantic, of archeol- ogists feverishly copying hieroglyphs by torchlight in a freshly discovered burial chamber; of philologists dangling over a precipice in some remote corner of the earth, taking impres- sions of an inscription carved in a cliff-face; of a solitary scholar working far into the night, puzzling out some ancient secret, long forgotten by humankind, from a brittle-leafed manuscript or patina-encrusted tablet. The allure is undeniable, and the literary and film worlds have made full use of it. An ancient language is indeed a thing of wonder – but so is every other language, all remarkable systems of conveying thoughts and ideas across time and space. And ancient languages, as far back as the very earliest attested, operate just like those to which the linguist has more immediate access, all with the same familiar elements – phonological, morphological, syntactic – and no perceptible vestiges of Neanderthal oddities. If there was a time when human language was characterized by features and strategies fundamentally unlike those we presently know, it was a time prior to the development of any attested or reconstructed language of antiquity. Perhaps, then, what makes an ancient language different is our awareness that it has outlived those for whom it was an intimate element of the psyche, not so unlike those rays of light now reaching our eyes that were emitted by their long-extinguished source when dinosaurs still roamed across the earth (or earlier) – both phantasms of energy flying to our senses from distant sources, long gone out. -

3-Art-Of-Indus-Valley.Pdf

Harappan civilization 2 Architecture 2 Drainage System 3 The planning of the residential houses were also meticulous. 4 Town Planning 4 Urban Culture 4 Occupation 5 Export import product of 5 Clothing 5 Important centres 6 Religious beliefs 6 Script 7 Authority and governance 7 Technology 8 Architecture Of Indus Valley Civilisation 9 The GAP 9 ARTS OF THE INDUS VALLEY 11 Stone Statues 12 MALE TORSO 12 Bust of a bearded priest 13 Male Dancer 14 Bronze Casting 14 DANCING GIRL 15 BULL 16 Terracotta 16 MOTHER GODDESS 17 Seals 18 Pashupati Seal 19 Copper tablets 19 Bull Seal 20 Pottery 21 PAINTED EARTHEN JAR 22 Beads and Ornaments 22 Toy Animal with moveable head 24 Page !1 of !26 Harappan civilization India has a continuous history covering a very long period. Evidence of neolithic habitation dating as far back as 7000 BC has been found in Mehrgarh in Baluchistan. However, the first notable civilization flourished in India around 2700 BC in the north western part of the Indian subcontinent, covering a large area. The civilization is referred to as the Harappan civilization. Most of the sites of this civilization developed on the banks of Indus, Ghaggar and its tributaries. Architecture The excavations at Harappa and Mohenjodaro and several other sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation revealed the existence of a very modern urban civilisation with expert town planning and engineering skills. The very advanced drainage system along with well planned roads and houses show that a sophisticated and highly evolved culture existed in India before the coming of the Aryans. -

First Capitals of Armenia and Georgia: Armawir and Armazi (Problems of Early Ethnic Associations)

First Capitals of Armenia and Georgia: Armawir and Armazi (Problems of Early Ethnic Associations) Armen Petrosyan Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Yerevan The foundation legends of the first capitals of Armenia and Georgia – Armawir and Armazi – have several common features. A specific cult of the moon god is attested in both cities in the triadic temples along with the supreme thunder god and the sun god. The names of Armawir and Armazi may be associated with the Anatolian Arma- ‘moon (god).’ The Armenian ethnonym (exonym) Armen may also be derived from the same stem. The sacred character of cultic localities is extremely enduring. The cults were changed, but the localities kept their sacred character for millennia. At the transition to a new religious system the new cults were often simply imposed on the old ones (e.g., the old temple was renamed after a new deity, or the new temple was built on the site or near the ruins of the old one). The new deities inherited the characteristics of the old ones, or, one may say, the old cults were simply renamed, which could have been accompanied by some changes of the cult practices. Evidently, in the new system more or less comparable images were chosen to replace the old ones: similarity of functions, rituals, names, concurrence of days of cult, etc (Petrosyan 2006: 4 f.; Petrosyan 2007a: 175).1 On the other hand, in the course of religious changes, old gods often descend to the lower level of epic heroes. Thus, the heroes of the Armenian ethnogonic legends and the epic “Daredevils of Sasun” are derived from ancient local gods: e.g., Sanasar, who obtains the 1For numerous examples of preservation of pre-Urartian and Urartian holy places in medieval Armenia, see, e.g., Hmayakyan and Sanamyan 2001). -

Indus Valley Civilization

Name: edHelper Indus Valley Civilization A long, long time ago, there was a group of people called the Aryans. The Aryans were possibly from southern Russia and Central Asia. As nomads, they never liked to linger in one place. Instead, they much preferred to herd their animals by moving them from one spot to another. About 3,600 years ago, the Aryans decided to change their lifestyle. They wanted to give up endless wandering. They wanted to have a permanent settlement that they could call home. When they arrived in India, they did exactly that. As the Aryans learned to adapt to their new environment, they brought with them their religion and customs. Their culture later became the foundation of the Indian culture and led people to believe that it was India's oldest civilization. That notion changed completely in 1921! In 1921, archaeologists unearthed two ancient cities - Harappa and Mohenjo-daro - near the Indus River. Both sites predated the Aryans' settlement by about 1,000 years. The discovery, undoubtedly, was a surprise to everybody. Right away, it pushed the Indian history back even further than it already was. Scholars around the world termed the newly found culture "the Indus valley civilization." Some also called it "the Harappan civilization" because Harappa was the first city the archaeologists dug out. The Indus River lies on the western side of the Indian subcontinent. Today, both the river itself and the two ancient cities fall within the confines of Pakistan. The excavations indicated that people of this ancient culture were excellent city planners. -

Pictograms: Purely Pictorial Symbols

toponymy course 10. Writing systems Ferjan Ormeling This chapter shows the semantic, phonetic and graphic aspects of language. It traces the development of the graphic aspects from Sumeria 3500BC, from logographic or ideographic via syllabic into alphabetic scripts resulting in a number of script families. It gives examples of the various scripts in maps (see underlined script names) and finally deals with combination of scripts on maps. 03/07/2011 1 Meaning, sound and looks What is the name? - Is it what it means? - Is it what it sounds? - Is it what it looks? 03/07/2011 2 Meaning: the semantic aspect As long as a name is what it means, both its sound and its looks (spelling) are only relevant as far as they support the meaning. The name ‘Nederland’ is wat it means to our neighbours: ‘Low country’. So they translate it for instance into ‘Pays- Bas’ (French) or Netherlands (English) or Niederlande (German), even though that does neither sound nor look like ‘Nederland’. To Romans and Italians, however, the names Qart Hadasht and Neapolis had never been what they meant (‘new towns’). So they became what they sounded: Carthago (to the Roman ear) and Napoli. 03/07/2011 3 Sound: the phonetic aspect As soon as a name is what it sounds, its meaning has become irrelevant. Its looks (spelling) then may or may not be adapted to its sound. The dominance of the phonetic aspect to a name (the ‘oral tradition’) allows the name to degenerate graphically. Eventually, the name may be adapted semantically to its perceived sound, through a process called ‘popular etymology’. -

The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized

American Journal of Applied Psychology 2017; 6(5): 88-92 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajap doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 ISSN: 2328-5664 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5672 (Online) The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized Marcienne Martin ORACLE Laboratory, Observatory of Arts, Civilizations and Literatures, in Their Environment, University of Reunion Island, France Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Marcienne Martin. The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized. American Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 6, No. 5, 2017, pp. 88-92. doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 Received: January 16, 2017; Accepted: January 25, 2017; Published: October 18, 2017 Abstract: The digital paradigm to which these new technologies (NTIC) belong is at the origin of particular linguistic practices. Internet is an innovator in this field. Indeed, its users want their written communications to be as fast as during oral exchanges; they will choose their knowledge to write on a saving in expressive type. Also wishing to transmit feelings and emotions, they will call upon an iconography, which uses the diacritics as material serving creation of logograms. This redundancy of a diverted punctuation of its original use, but being used “to punctuate” the speech by figurines translating the emotional state of the speaker, is a characteristic of this numerical space. Through the analysis of the corpus taken on the Internet and put in comparison with the hieroglyphic system introduced by Champollion Le Jeune [5] and the graphic evolution of some ideograms, it will be shown that it is always about the same used model, in which a key always initiates a semantic field, and that this process orders a reorganization of the objects of the world through a new scriptural writing. -

Quick Reference Guide to ADA Signage

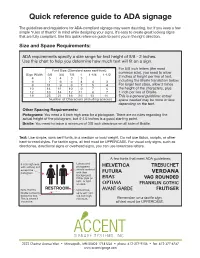

Quick reference guide to ADA signage The guidelines and regulations for ADA-compliant signage may seem daunting, but if you keep a few simple “rules of thumb” in mind while designing your signs, it’s easy to create great looking signs that are fully compliant. Use this quick reference guide to point you in the right direction. Size and Space Requirements: ADA requirements specify a size range for text height of 5/8 - 2 inches. Use this chart to help you determine how much text will fit on a sign. For 5/8 inch letters (the most common size), you need to allow 2 inches of height per line of text, including the Braille translation below. For larger text sizes, allow 2 times the height of the characters, plus 1 inch per line of Braille. This is a general guideline; actual space needed may be more or less depending on the text. Other Spacing Requirements: Pictograms: You need a 6 inch high area for a pictogram. There are no rules regarding the actual height of the pictogram, but 4-4.5 inches is a good starting point. Braille: You need to leave a minimum of 3/8 inch clearance on all side of Braille. Text: Use simple, sans serif fonts, in a medium or bold weight. Do not use italics, scripts, or other hard-to-read styles. For tactile signs, all text must be UPPERCASE. For visual only signs, such as directories, directional signs or overhead signs, you can use lowercase letters. A few fonts that meet ADA guidelines: 6 inch high area Letters and with nothing in it pictograms except the should contrast pictogram. -

Arts of the Indus Valley

2 ARTS OF THE INDUS VALLEY HE arts of the Indus Valley Civilisation emerged during Tthe second half of the third millennium BCE. The forms of art found from various sites of the civilisation include sculptures, seals, pottery, jewellery, terracotta figures, etc. The artists of that time surely had fine artistic sensibilities and a vivid imagination. Their delineation of human and animal figures was highly realistic in nature, since the anatomical details included in them were unique, and, in the case of terracotta art, the modelling of animal figures was done in an extremely careful manner. The two major sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation, along the Indus river—the cities of Harappa in the north and Mohenjodaro in the south—showcase one of earliest examples of civic planning. Other markers were houses, markets, storage facilities, offices, public baths, etc., arranged in a grid-like pattern. There was also a highly developed drainage system. While Harappa and Mohenjodaro are situated in Pakistan, the important sites excavated in India are Lothal and Dholavira in Gujarat, Rakhigarhi in Haryana, Bust of a bearded priest Ropar in Punjab, Kalibangan in Rajasthan, etc. Stone Statues Statues whether in stone, bronze or terracotta found in Harappan sites are not abundant, but refined. The stone statuaries found at Harappa and Mohenjodaro are excellent examples of handling three-dimensional volumes. In stone are two male figures—one is a torso in red sandstone and the other is a bust of a bearded man in soapstone—which are extensively discussed. The figure of the bearded man, interpreted as a priest, is draped in a shawl coming under the right arm and covering the left shoulder.