The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Episode 15: Neil Strauss Show Notes and Links at Tim.Blog/Podcast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subjectivity in American Popular Metal: Contemporary Gothic, the Body, the Grotesque, and the Child

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Glasgow Theses Service Subjectivity In American Popular Metal: Contemporary Gothic, The Body, The Grotesque, and The Child. Sara Ann Thomas MA (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow January 2009 © Sara Thomas 2009 Abstract This thesis examines the subject in Popular American Metal music and culture during the period 1994-2004, concentrating on key artists of the period: Korn, Slipknot, Marilyn Manson, Nine Inch Nails, Tura Satana and My Ruin. Starting from the premise that the subject is consistently portrayed as being at a time of crisis, the thesis draws on textual analysis as an under appreciated approach to popular music, supplemented by theories of stardom in order to examine subjectivity. The study is situated in the context of the growing area of the contemporary gothic, and produces a model of subjectivity specific to this period: the contemporary gothic subject. This model is then used throughout to explore recurrent themes and richly symbolic elements of the music and culture: the body, pain and violence, the grotesque and the monstrous, and the figure of the child, representing a usage of the contemporary gothic that has not previously been attempted. Attention is also paid throughout to the specific late capitalist American cultural context in which the work of these artists is situated, and gives attention to the contradictions inherent in a musical form which is couched in commodity culture but which is highly invested in notions of the ‘Alternative’. In the first chapter I propose the model of the contemporary gothic subject for application to the work of Popular Metal artists of the period, drawing on established theories of the contemporary gothic and Michel Foucault’s theory of confession. -

An Uncomfortable Book About Relationships

SNEAK PREVIEW. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION. The TRUTH AN UNCOMFORTABLE BOOK ABOUT RELATIONSHIPS Neil Strauss New York Times Bestselling Author of THE GAME The TRUTH AN UNCOMFORTABLE BOOK ABOUT RELATIONSHIPS Neil Strauss The following pages contain one of the most ter- rifying and obscene words in the English language: commitment. Specifically the type of commitment that often precedes or follows love and sex. A lack of commitment, too much commitment, a poorly chosen commitment, and misunderstandings about commitment have led to murders, suicides, wars, and a whole lot of grief. They have also led to this book, which is an attempt to figure out where so many people go wrong, again and again, when it comes to relationships and marriage— and if there’s a better way to live, love, and make love. This, however, is not a journey that was undertaken for journalistic purposes. It is a painfully honest account of a life crisis that was forced on me as a consequence of my own behavior. Like most per- sonal journeys, it starts in a place of darkness, confusion, and foolishness. As such, it requires sharing a lot of things I’m not proud of— and a few things I feel like I should regret a whole lot more than I actually do. Because, unfortunately, I am not the hero in this tale. I am the villain. If you are reading this, please stop now. Do NOT turn the page. Ingrid, If this is you, really, don’t read this. Don’t you have email to check or something? Or have you seen the video with that cat who’s doing a human-like thing? It’s hilarious - - maybe you should watch it. -

Pick-Up Artists

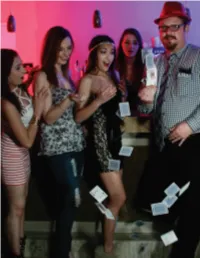

PICK-UP ARTISTS PICk-UP ARTISTS PUA LINGO t’s 8pm on Friday at Ivy, horror or amusement 101 Could it be that any man who’s the modern PUA industry in the late Sydney’s classiest pick- as he makes a clumsy prepared to study PUA theory then put ’80s. Jeffries, a devotee of personal Cyber pulling up joint. I’m standing attempt to raunch Average Frustrated it into practice really can nail as many development programs, brought a five- Chump (AFC) next to pick-up artist things up. He doesn’t Men who enjoy limited success hot babes as he pleases? year dry patch to an end by using (PUA) coach Damien wait long. Paul with women due to a lack of Ever since women were Neuro-Linguistic Programming to seduce The mainstreaming of pick-up coaching coincided with the rise of online dating but, insight into them (that is, Chick crack surprisingly, seduction gurus have little advice to offer about how to bust a digital Diecke while he asks three abruptly leaves the most non-PUAs). Topics — such as royal invented, men have been women. He then began offering ‘Speed aspiring pants men — let’s set and returns to get weddings, Oprah’s weight issues, trying to work out how to Seduction’ seminars to men, training move on a girl. Here’s GQ’s tips: psychic abilities — it’s easy call them John, Paul and George — to Diecke’s feedback on his to engage women in get them in the sack. And, them in the Jedi mind tricks he deployed state their goals for the evening. -

Successful Masculinity in Search of the Alpha Within

UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE School of Communication, Media and Theatre Successful Masculinity In Search of the Alpha Within Dermot Lyons Pro Gradu – Master’s Thesis June 2015 UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE School of Communication, Media and Theatre LYONS, DERMOT: Successful Masculinity: In Search of the Alpha Within Pro Gradu – Master’s Thesis, 133 pages. Journalism and Communication / Media Culture June 2015 Abstract Pickup artists and the seduction community have gone from being an underground network of workshop and internet based teachers and students, to, following the publication of Neil Strauss’ book ‘The Game: Penetrating the Secret Society of Pickup Artists’, a movement entering the wider public consciousness, a subculture of (primarily) men who wish to get better at meeting, sleeping with, and dating women. They try to make the transformation from men who are not successful socially or with women, termed ‘AFC’s or ‘Average Frustrated Chumps’ in the seduction community, to PUAs, or PickUp Artists. There are now seduction companies, TV shows, radio shows, podcasts, blogs, books, forums, websites, chat rooms, and community groups for major cities all across the world. This material is not always practiced or preached in a mainstream-safe way, but rather is done by breaking through groupthink, going against perceived norms, not being politically correct, and using the findings of evolutionary psychology and life coaching. The thinking behind this is: Everything can be taught, so why not how to get girls? Game is (supposed to be) a fun, pleasurable way to improve your overall self: diet, exercise, hygiene, education, career, living circumstance, behavior, sociability – all are looked at towards bettering an overall enhanced version of yourself, almost quantifiable, to be the most optimal self you can be, where you are having a good life, and women are a part of that life, who may join you on your own individual journey as a man. -

Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis CONTENTS

Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................... 1 What Techniques Do Media Manipulators Use? ....... 33 Understanding Media Manipulation ............................ 2 Participatory Culture ........................................... 33 Who is Manipulating the Media? ................................. 4 Networks ............................................................. 34 Internet Trolls ......................................................... 4 Memes ................................................................. 35 Gamergaters .......................................................... 7 Bots ...................................................................... 36 Hate Groups and Ideologues ............................... 9 Strategic Amplification and Framing ................. 38 The Alt-Right ................................................... 9 Why is the Media Vulnerable? .................................... 40 The Manosphere .......................................... 13 Lack of Trust in Media ......................................... 40 Conspiracy Theorists ........................................... 17 Decline of Local News ........................................ 41 Influencers............................................................ 20 The Attention Economy ...................................... 42 Hyper-Partisan News Outlets ............................. 21 What are the Outcomes? .......................................... -

Music Sampling and Copyright Law

CACPS UNDERGRADUATE THESIS #1, SPRING 1999 MUSIC SAMPLING AND COPYRIGHT LAW by John Lindenbaum April 8, 1999 A Senior Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My parents and grandparents for their support. My advisor Stan Katz for all the help. My research team: Tyler Doggett, Andy Goldman, Tom Pilla, Arthur Purvis, Abe Crystal, Max Abrams, Saran Chari, Will Jeffrion, Mike Wendschuh, Will DeVries, Mike Akins, Carole Lee, Chuck Monroe, Tommy Carr. Clockwork Orange and my carrelmates for not missing me too much. Don Joyce and Bob Boster for their suggestions. The Woodrow Wilson School Undergraduate Office for everything. All the people I’ve made music with: Yamato Spear, Kesu, CNU, Scott, Russian Smack, Marcus, the Setbacks, Scavacados, Web, Duchamp’s Fountain, and of course, Muffcake. David Lefkowitz and Figurehead Management in San Francisco. Edmund White, Tom Keenan, Bill Little, and Glenn Gass for getting me started. My friends, for being my friends. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.....................................................................................……………………...1 History of Musical Appropriation........................................................…………………6 History of Music Copyright in the United States..................................………………17 Case Studies....................................................................................……………………..32 New Media......................................................................................……………………..50 -

Created in God's Image

CREATED IN GOD’S IMAGE FROM HEGEMONY TO PARTNERSHIP CREATED IN GOD’S IMAGE FROM HEGEMONY TO PARTNERSHIP CREATED IN GOD’S IMAGE IN GOD’S IMAGE CREATED FROM HEGEMONY TO PARTNERSHIP PARTNERSHIP TO HEGEMONY FROM Created in God’s Image: From Hegemony to Partnership is a church manual on men as partners for promoting positive masculinities. It is a dynamic resource on men, gender and masculinity from the stand point of the Christian faith. The concepts of masculinity and gender are explored with the aim of enabling men to become more conscious of gender as a social construct that affects their own lives as well as that of women. Masculinity is explored from lived experiences as well as from the perspective of social practices, behaviour and power constructions through which men become conscious of themselves as gendered subjects. Various approaches are used to examine and question hegemonic masculinity and for creating enabling environments in which men and women work towards re-defining, re-ordering, re-orienting and thus transforming dominant forms of masculinity. The intention is to affirm positive masculinities and not to demonize men or to instill feelings of guilt and powerlessness in them. Men are enabled to peel away layers of gender constructions which have played a key role in defining manhood in specific cultural, religious, economic, political and social contexts. The manual includes theological and biblical resources, stories, sermon notes and eight modules on men, masculinity and gender. The modules include activities for discussion on how men’s experiences, beliefs and values form the foundational bases of masculinity. -

Art of “The Pickup.” Specifically, Being Able the Term Gained Great Popularity With

9 DAM! The of ART the PICKUP Story and photos by Emily K. Rabasto Did it hurt when you fell from heaven? I seem to have lost my phone number. Can I have yours? Did you sit in a pile of sugar? ’Cause you have a pretty sweet… DAM! 10 ickup lines are bullshit. It’s not you, it’s just a line.” Matthew Burks bristles ‘Pwhen he hears men ap- proach women this way. The 25-year-old photography assistant from Sacramento recently took lessons on approaching women from a self-pro- claimed pickup artist. Pickup artists, commonly known as PUAs, consider themselves masters of the to attract or pick up the interest of any woman.art of “the pickup.” Specifically, being able The term gained great popularity with “The Game: Penetrating the Secret Society ofthe Pickup 2005 releaseArtists” of by the author non-fiction and journal book- ist Neil Strauss. The book chronicles the author’s real-life experience entering the Sacramento pickup artist Bryan Barton, right, talks with a woman after a free observation subculture of seduction. class he offered to his students during a speed dating event on Feb. 11, 2015 in Sacramento. The television network VH1 also helped During the event, Barton and his students critiqued men on their interactions with women. make the term mainstream through its reality TV show, The Pickup Artist hosted by Erik von Markovik, more commonly “I want to be who I really am...I have interesting known by his stage name, “Mystery.” During the show, contestants would be stories. -

“I Am Your Faggot Anti-Pope”: an Exploration of Marilyn Manson As a Transgressive Artist

European journal of American studies 12-2 | 2017 Summer 2017, including Special Issue: Popularizing Politics: The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election “I Am Your Faggot Anti-Pope”: An Exploration of Marilyn Manson as a Transgressive Artist Coco d’Hont Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12098 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12098 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Coco d’Hont, « “I Am Your Faggot Anti-Pope”: An Exploration of Marilyn Manson as a Transgressive Artist », European journal of American studies [Online], 12-2 | 2017, document 14, Online since 01 August 2017, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12098 ; DOI : 10.4000/ ejas.12098 This text was automatically generated on 19 April 2019. Creative Commons License “I Am Your Faggot Anti-Pope”: An Exploration of Marilyn Manson as a Transgres... 1 “I Am Your Faggot Anti-Pope”: An Exploration of Marilyn Manson as a Transgressive Artist Coco d’Hont 1 “As a performer,” Marilyn Manson announced in his autobiography, “I wanted to be the loudest, most persistent alarm clock I could be, because there didn’t seem to be any other way to snap society out of its Christianity- and media-induced coma” (Long Hard Road 80).i With this mission statement, expressed in 1998, the performer summarized a career characterized by harsh-sounding music, disturbing visuals, and increasingly controversial live performances. At first sight, the red thread running through the albums he released during the 1990s is a harsh attack on American ideologies. On his debut album Portrait of an American Family (1994), for example, Manson criticizes ideological constructs such as the nuclear family, arguing that the concept is often used to justify violent pro-life activism.ii Proclaiming that “I got my lunchbox and I’m armed real well” and that “next motherfucker’s gonna get my metal,” he presents himself as a personification of teenage angst determined to destroy his bullies, be they unfriendly classmates or the American government. -

SEXUAL MARKET VALUE: Economic Metaphor in “Pickup Artist” Handbooks

SEXUAL MARKET VALUE: Economic metaphor in “pickup artist” handbooks Sarah Martin A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree MA Economy & Society Graduate School for Social Research 2018 ABSTRACT Sexual sociality is conceptualised colloquially and academically as a market. However, attempts to apply market analysis tools from economics to modelling sexual stratification result in tautology, where opposite findings can equally be explained away as utility-maximising functions. The predominance of market metaphor may result from sexual selection feeling like a market, rather than it functioning as a market. In this qualitative content analysis of four Anglophone "pickup artist" handbooks, economic metaphor is shown to be used to describe the process for men of attracting women with the aim of initiating sexual interaction. This use of economic metaphor indicates that the heterosexual men that write and read these books partially understand sexual interactions in terms of economic experiences and that this might influence their actions in sexual social space. The emergent metaphorical structure of the sexual market place was coherent across the corpus and provides a perspective on how heterosexual men conceptualise sexual sociality and plan future action on the basis of their understanding of market functions. This corpus metaphorically constructs sexual sociality as a market. Individuals participating in the market are commodity-producing-commodities and individual actors at the same time. In this market structure, men produce and sell attention (time, money, and emotion) and are paid with sex (physical, sexual interaction) produced by women. Women buy attention from men and pay with sex. Salesperson is a high-power role and buyer is a low-power role in this metaphorical market. -

From Pick-Up Artists to Incels: Con(Fidence)

From pick-up artists to incels: con(fidence) games,networked misogyny, and the failure of neoliberalism LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/102183/ Version: Published Version Article: Bratich, Jack and Banet-Weiser, Sarah (2019) From pick-up artists to incels: con(fidence) games, networked misogyny, and the failure of neoliberalism. International Journal of Communication, 13. 5003 - 5027. ISSN 1932-8036 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ International Journal of Communication 13(2019), Feature 5003–5027 1932–8036/2019FEA0002 From Pick-Up Artists to Incels: Con(fidence) Games, Networked Misogyny, and the Failure of Neoliberalism JACK BRATICH1 Rutgers University, USA SARAH BANET-WEISER London School of Economics and Political Science, UK Between 2007 and 2018, the pick-up artist community—“gurus” who teach online networks of heterosexual men to seduce women—gave rise to a different online community, that of “incels,” who create homosocial bonds over their inability to become a pick-up artist. In this article, we offer a conjunctural analysis of this shift and argue that this decade represents a decline in, or even a failure of, neoliberalism’s ability to secure subjects within its political rationality. -

Capturing-Sound-How-Technology-Has-Changed-Music.Pdf

ROTH FAMILY FOUNDATION Music in America Imprint Michael P. Roth and Sukey Garcetti have endowed this imprint to honor the memory of their parents, Julia and Harry Roth, whose deep love of music they wish to share with others. This publication has been supported by a subvention from the Gustave Reese Publication Endowment Fund of the American Musicological Society. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Music in America Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Associates, which is supported by a major gift from Sukey and Gil Garcetti, Michael Roth, and the Roth Family Foundation. CAPTURING SOUND H O W CAPT T U E C R H N I O N L O G G Y S UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS H A S O C H U A N N G E D D M BERKELEY LOS ANGELES LONDON U S I C tz mark ka University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England “The Entertainer” written by Billy Joel © 1974, JoelSongs [ASCAP]. All rights reserved. Used by permission. © 2004 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Katz, Mark, 1970–. Capturing sound : how technology has changed music / Mark Katz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-24196-7 (cloth : alk. paper)— ISBN 0-520-24380-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Sound recording industry. 2. Music and technology. I. Title. ml3790.k277 2005 781.49—dc22 2004011383 Manufactured in the United States of America 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10987654 321 The paper used in this publication is both acid-free and totally chlorine-free (TCF).