From Pick-Up Artists to Incels: Con(Fidence) Games, Networked Misogyny, and the Failure of Neoliberalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unlikely Hegemons

sponding to this. Employment, as wage labour, ne- Stiegler’s critique of automation is inarguably cessarily implies proletarianisation and alienation, dialectical and, in its mobilisation of the pharmakon, whereas for Marx, ‘work can be fulflling only if it impeccably Derridean. Yet it leaves unanswered – ceases to be wage labour and becomes free.’ The de- for the moment at least, pending a second volume – fence of employment on the part of the left and la- the question of the means through which the trans- bour unions is then castigated as a regressive posi- ition from employment to work might be effected. tion that, while seeking to secure the ‘right to work’, This would surely require not only the powers of in- only shores up capitalism through its calls for the dividual thought, knowledge, refection and critique maintenance of wage labour. Contrariwise, automa- that Stiegler himself affrms and demonstrates in tion has the potential to fnally release the subject Automatic Society, but also their collective practice from the alienation of wage labour so as to engage and mobilisation. What is also passed over in Stie- in unalienated work, properly understood as the pur- gler’s longer term perspectives is the issue of how suit, practice and enjoyment of knowledge. What such collective practices, such as already exist, are currently stands in the way of the realisation of ful- to respond to the more immediate and contempor- flling work, aside from an outmoded defense of em- ary effects of automation, if not through the direct ployment, Stiegler notes, is the capture of the ‘free contestation of the conditions and terms of employ- time’ released from employment in consumption, ment and unemployment. -

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

![Arxiv:2001.07600V5 [Cs.CY] 8 Apr 2021 Leged Crisis (Lilly 2016)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6394/arxiv-2001-07600v5-cs-cy-8-apr-2021-leged-crisis-lilly-2016-86394.webp)

Arxiv:2001.07600V5 [Cs.CY] 8 Apr 2021 Leged Crisis (Lilly 2016)

The Evolution of the Manosphere Across the Web* Manoel Horta Ribeiro,♠;∗ Jeremy Blackburn,4 Barry Bradlyn,} Emiliano De Cristofaro,r Gianluca Stringhini,| Summer Long,} Stephanie Greenberg,} Savvas Zannettou~;∗ EPFL, Binghamton University, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign University♠ College4 London, Boston} University, Max Planck Institute for Informatics r Corresponding authors: manoel.hortaribeiro@epfl.ch,| ~ [email protected] ∗ Abstract However, Manosphere communities are scattered through the Web in a loosely connected network of subreddits, blogs, We present a large-scale characterization of the Manosphere, YouTube channels, and forums (Lewis 2019). Consequently, a conglomerate of Web-based misogynist movements focused we still lack a comprehensive understanding of the underly- on “men’s issues,” which has prospered online. Analyzing 28.8M posts from 6 forums and 51 subreddits, we paint a ing digital ecosystem, of the evolution of the different com- comprehensive picture of its evolution across the Web, show- munities, and of the interactions among them. ing the links between its different communities over the years. Present Work. In this paper, we present a multi-platform We find that milder and older communities, such as Pick longitudinal study of the Manosphere on the Web, aiming to Up Artists and Men’s Rights Activists, are giving way to address three main research questions: more extreme ones like Incels and Men Going Their Own Way, with a substantial migration of active users. Moreover, RQ1: How has the popularity/levels of activity of the dif- our analysis suggests that these newer communities are more ferent Manosphere communities evolved over time? toxic and misogynistic than the older ones. -

The Alt-Right Comes to Power by JA Smith

USApp – American Politics and Policy Blog: Long Read Book Review: Deplorable Me: The Alt-Right Comes to Power by J.A. Smith Page 1 of 6 Long Read Book Review: Deplorable Me: The Alt- Right Comes to Power by J.A. Smith J.A Smith reflects on two recent books that help us to take stock of the election of President Donald Trump as part of the wider rise of the ‘alt-right’, questioning furthermore how the left today might contend with the emergence of those at one time termed ‘a basket of deplorables’. Deplorable Me: The Alt-Right Comes to Power Devil’s Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump and the Storming of the Presidency. Joshua Green. Penguin. 2017. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. Angela Nagle. Zero Books. 2017. Find these books: In September last year, Hillary Clinton identified within Donald Trump’s support base a ‘basket of deplorables’, a milieu comprising Trump’s newly appointed campaign executive, the far-right Breitbart News’s Steve Bannon, and the numerous more or less ‘alt right’ celebrity bloggers, men’s rights activists, white supremacists, video-gaming YouTubers and message board-based trolling networks that operated in Breitbart’s orbit. This was a political misstep on a par with putting one’s opponent’s name in a campaign slogan, since those less au fait with this subculture could hear only contempt towards anyone sympathetic to Trump; while those within it wore Clinton’s condemnation as a badge of honour. Bannon himself was insouciant: ‘we polled the race stuff and it doesn’t matter […] It doesn’t move anyone who isn’t already in her camp’. -

Protocol for Direct Assistance for the Capital Gazette Families Fund

Protocol for Direct Assistance for the Capital Gazette Families Fund BACKGROUND On June 28, 2018 a gunman forced his way into the Capital Gazette newsroom in Annapolis with a shotgun killing five people and injuring two others. Officers responded to the scene within a minute of the rampage and found employees fleeing from the building. The suspect was found hiding under a desk and was arrested. The Annapolis community was shocked and heartbroken. Grieving colleagues began covering the story — some of them immediately upon escaping the building. The following morning, the Community Foundation of Anne Arundel County (CFAAC) was contacted by the Baltimore Sun Media Group and asked to administer the funds that were being donated to support the victims and their families. The Capital Gazette Families Fund (Fund) was established in coordination with tronc, Inc., to honor the lives of the five employees that were killed during the tragic shooting. While we know financial gifts cannot erase the traumatic impacts of tragedy, we hope that these gifts, given by thousands of people from around the world, will be a symbol of caring and help the employees and their families begin to heal. Through this fund we cannot solve all of the problems arising from this event, we cannot bring back those who were killed, nor erase that which was witnessed and endured by the survivors. The gifts made from this Fund are qualitatively different from other sources of tragedy relief. These gifts are not based on any economic loss or expenses incurred as a result of the incident. Additional assistance may be provided by the Maryland Criminal Injuries Compensation Board and other sources. -

From Disney to Disaster: the Disney Corporation’S Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks

From Disney to Disaster: The Disney Corporation’s Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks BY Kelsey N. Reese Spring 2021 WMNST 492W: Senior Capstone Seminar Dr. Jill Wood Reese 2 INTRODUCTION The popularized phrase “celebrity trainwreck” has taken off in the last ten years, and the phrase actively evokes specified images (Doyle, 2017). These images usually depict young women hounded by paparazzi cameras that are most likely drunk or high and half naked after a wild night of partying (Doyle, 2017). These girls then become the emblem of celebrity, bad girl femininity (Doyle, 2017; Kiefer, 2016). The trainwreck is always a woman and is usually subject to extra attention in the limelight (Doyle, 2017). Trainwrecks are in demand; almost everything they do becomes front page news, especially if their actions are seen as scandalous, defamatory, or insane. The exponential growth of the internet in the early 2000s created new avenues of interest in celebrity life, including that of social media, gossip blogs, online tabloids, and collections of paparazzi snapshots (Hamad & Taylor, 2015; Mercer, 2013). What resulted was 24/7 media access into the trainwreck’s life and their long line of outrageous, commiserable actions (Doyle, 2017). Kristy Fairclough coined the term trainwreck in 2008 as a way to describe young, wild female celebrities who exemplify the ‘good girl gone bad’ image (Fairclough, 2008; Goodin-Smith, 2014). While the coining of the term is rather recent, the trainwreck image itself is not; in their book titled Trainwreck, Jude Ellison Doyle postulates that the trainwreck classification dates back to feminism’s first wave with Mary Wollstonecraft (Anand, 2018; Doyle, 2017). -

"If You're Ugly, the Blackpill Is Born with You": Sexual Hierarchies, Identity Construction, and Masculinity on an Incel Forum Board

University of Dayton eCommons Joyce Durham Essay Contest in Women's and Gender Studies Women's and Gender Studies Program 2020 "If You're Ugly, the Blackpill is Born with You": Sexual Hierarchies, Identity Construction, and Masculinity on an Incel Forum Board Josh Segalewicz University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/wgs_essay Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons eCommons Citation Segalewicz, Josh, ""If You're Ugly, the Blackpill is Born with You": Sexual Hierarchies, Identity Construction, and Masculinity on an Incel Forum Board" (2020). Joyce Durham Essay Contest in Women's and Gender Studies. 20. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/wgs_essay/20 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Women's and Gender Studies Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Joyce Durham Essay Contest in Women's and Gender Studies by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. "If You're Ugly, the Blackpill is Born with You": Sexual Hierarchies, Identity Construction, and Masculinity on an Incel Forum Board by Josh Segalewicz Honorable Mention 2020 Joyce Durham Essay Contest in Women's and Gender Studies "If You're Ugly, The Blackpill is Born With You": Sexual Hierarchies, Identity Construction, and Masculinity on an Incel Forum Board Abstract: The manosphere is one new digital space where antifeminists and men's rights activists interact outside of their traditional social networks. Incels, short for involuntary celibates, exist in this space and have been labeled as extreme misogynists, white supremacists, and domestic terrorists. -

Alone Together: Exploring Community on an Incel Forum

Alone Together: Exploring Community on an Incel Forum by Vanja Zdjelar B.A. (Hons., Criminology), Simon Fraser University, 2016 B.A. (Political Science and Communication), Simon Fraser University, 2016 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Criminology Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Vanja Zdjelar 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY FALL 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Vanja Zdjelar Degree: Master of Arts Thesis title: Alone Together: Exploring Community on an Incel Forum Committee: Chair: Bryan Kinney Associate Professor, Criminology Garth Davies Supervisor Associate Professor, Criminology Sheri Fabian Committee Member University Lecturer, Criminology David Hofmann Examiner Associate Professor, Sociology University of New Brunswick ii Abstract Incels, or involuntary celibates, are men who are angry and frustrated at their inability to find sexual or intimate partners. This anger has repeatedly resulted in violence against women. Because incels are a relatively new phenomenon, there are many gaps in our knowledge, including how, and to what extent, incel forums function as online communities. The current study begins to fill this lacuna by qualitatively analyzing the incels.co forum to understand how community is created through online discourse. Both inductive and deductive thematic analyses were conducted on 17 threads (3400 posts). The results confirm that the incels.co forum functions as a community. Four themes in relation to community were found: The incel brotherhood; We can disagree, but you’re wrong; We are all coping here; and Will the real incel come forward. -

Subjectivity in American Popular Metal: Contemporary Gothic, the Body, the Grotesque, and the Child

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Glasgow Theses Service Subjectivity In American Popular Metal: Contemporary Gothic, The Body, The Grotesque, and The Child. Sara Ann Thomas MA (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow January 2009 © Sara Thomas 2009 Abstract This thesis examines the subject in Popular American Metal music and culture during the period 1994-2004, concentrating on key artists of the period: Korn, Slipknot, Marilyn Manson, Nine Inch Nails, Tura Satana and My Ruin. Starting from the premise that the subject is consistently portrayed as being at a time of crisis, the thesis draws on textual analysis as an under appreciated approach to popular music, supplemented by theories of stardom in order to examine subjectivity. The study is situated in the context of the growing area of the contemporary gothic, and produces a model of subjectivity specific to this period: the contemporary gothic subject. This model is then used throughout to explore recurrent themes and richly symbolic elements of the music and culture: the body, pain and violence, the grotesque and the monstrous, and the figure of the child, representing a usage of the contemporary gothic that has not previously been attempted. Attention is also paid throughout to the specific late capitalist American cultural context in which the work of these artists is situated, and gives attention to the contradictions inherent in a musical form which is couched in commodity culture but which is highly invested in notions of the ‘Alternative’. In the first chapter I propose the model of the contemporary gothic subject for application to the work of Popular Metal artists of the period, drawing on established theories of the contemporary gothic and Michel Foucault’s theory of confession. -

Post-Postfeminism?: New Feminist Visibilities in Postfeminist Times

FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 16, NO. 4, 610–630 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2016.1193293 Post-postfeminism?: new feminist visibilities in postfeminist times Rosalind Gill Department of Sociology, City University, London, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article contributes to debates about the value and utility Postfeminism; neoliberalism; of the notion of postfeminism for a seemingly “new” moment feminism; media magazines marked by a resurgence of interest in feminism in the media and among young women. The paper reviews current understandings of postfeminism and criticisms of the term’s failure to speak to or connect with contemporary feminism. It offers a defence of the continued importance of a critical notion of postfeminism, used as an analytical category to capture a distinctive contradictory-but- patterned sensibility intimately connected to neoliberalism. The paper raises questions about the meaning of the apparent new visibility of feminism and highlights the multiplicity of different feminisms currently circulating in mainstream media culture—which exist in tension with each other. I argue for the importance of being able to “think together” the rise of popular feminism alongside and in tandem with intensified misogyny. I further show how a postfeminist sensibility informs even those media productions that ostensibly celebrate the new feminism. Ultimately, the paper argues that claims that we have moved “beyond” postfeminism are (sadly) premature, and the notion still has much to offer feminist cultural critics. Introduction: feminism, postfeminism and generation On October 2, 2015 the London Evening Standard (ES) published its first glossy magazine of the new academic year. With a striking red, white, and black cover design it showed model Neelam Gill in a bright red coat, upon which the words “NEW (GEN) FEM” were superimposed in bold. -

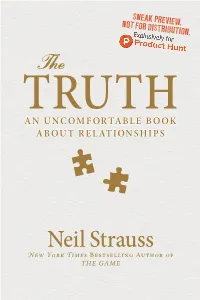

An Uncomfortable Book About Relationships

SNEAK PREVIEW. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION. The TRUTH AN UNCOMFORTABLE BOOK ABOUT RELATIONSHIPS Neil Strauss New York Times Bestselling Author of THE GAME The TRUTH AN UNCOMFORTABLE BOOK ABOUT RELATIONSHIPS Neil Strauss The following pages contain one of the most ter- rifying and obscene words in the English language: commitment. Specifically the type of commitment that often precedes or follows love and sex. A lack of commitment, too much commitment, a poorly chosen commitment, and misunderstandings about commitment have led to murders, suicides, wars, and a whole lot of grief. They have also led to this book, which is an attempt to figure out where so many people go wrong, again and again, when it comes to relationships and marriage— and if there’s a better way to live, love, and make love. This, however, is not a journey that was undertaken for journalistic purposes. It is a painfully honest account of a life crisis that was forced on me as a consequence of my own behavior. Like most per- sonal journeys, it starts in a place of darkness, confusion, and foolishness. As such, it requires sharing a lot of things I’m not proud of— and a few things I feel like I should regret a whole lot more than I actually do. Because, unfortunately, I am not the hero in this tale. I am the villain. If you are reading this, please stop now. Do NOT turn the page. Ingrid, If this is you, really, don’t read this. Don’t you have email to check or something? Or have you seen the video with that cat who’s doing a human-like thing? It’s hilarious - - maybe you should watch it. -

Status Threat, Social Concerns, and Conservative Media: a Look at White America and the Alt-Right

societies Article Status Threat, Social Concerns, and Conservative Media: A Look at White America and the Alt-Right Deena A. Isom 1,* , Hunter M. Boehme 2 , Toniqua C. Mikell 3, Stephen Chicoine 4 and Marion Renner 5 1 Department of Criminology & Criminal Justice and African American Studies Program, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29208, USA 2 Department of Criminal Justice, North Carolina Central University, Durham, NC 27707, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Crime and Justice Studies, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Dartmouth, MA 02747, USA; [email protected] 4 Bridge Humanities Corp Fellow and Department of Sociology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29208, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Criminology & Criminal Justice, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29208, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Racial and ethnic division is a mainstay of the American social structure, and today these strains are exacerbated by political binaries. Moreover, the media has become increasingly polarized whereby certain media outlets intensify perceived differences between racial and ethnic groups, political alignments, and religious affiliations. Using data from a recent psychological study of the Alt-Right, we assess the associations between perceptions of social issues, feelings of status threat, trust in conservative media, and affiliation with the Alt-Right among White Americans. We find concern over more conservative social issues along with trust in conservative media explain a large Citation: Isom, D.A.; Boehme, H.M.; portion of the variation in feelings of status threat among White Americans. Furthermore, more Mikell, T.C.; Chicoine, S.; Renner, M.