Performance Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Grey Lodge Occult Review™

May 1 2003 e.v. Issue #5 Grey Lodge Occult Review™ Gems from the Archives Selections from the archived Web-Material C O N T E N T S Mummeries of Resurrection The Cycle of Osiris in Finnegans Wake by Mark L. Troy The Man Who Invented Flying Saucers by John A. Keel SF, Occult Sciences, and Nazi Myths by Manfred Nagl Exegesis excerpts 1974-1982 "The Ten Major Principles of the Gnostic Revelation" by Philip K. Dick I Understand Philip K. Dick by Terence Mckenna Dr. Green and the Goblins of Langley by Jim Schnabel Brother Dave Morehouse D:.I:.A:. Remote Viewer & NDE Experiencer Excerpt from: Psychic Warrior by David Morehouse The Oberg Files by Blue Resonant Human, Ph.D. (Agent BlueBird) EXIT Communication to all Brethren (Information) from Robert De Grimston The Process - Church of the Final Judgement The Gitanjali or `song offerings' by Rabindranath Tagore with an introduction by William B. Yeats Rosa Alchemica by William B. Yeats (Note: PDF) John Dee by Charlotte Fell-Smith (Note: PDF) Serapis A Romance by Georg Ebers (Note: PDF) Home GLORidx Close Window Except where otherwise noted, Grey Lodge Occult Review™ is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. Grey Lodge Occult Review™ 2003 e.v. - Issue #5 Mummeries of Resurrection The Cycle of Osiris in Finnegans Wake Mark L. Troy Uppsala 1976 Doctoral dissertation at the University of Uppsala 1976 HTML version prepared by Eric Rosenbloom Kirby Mountain Composition & Graphics 2002 Note: Page numbers from the printed text have been retained in the table of contents to use as approximate guides for the references in the bibliographies, line index, and elsewhere. -

2005Newtitle 000.Pdf

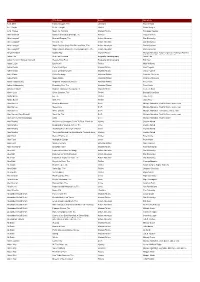

The Combined ® Book Exhibit Welcome to BookExpo America 2005 Dear Industry Colleague: BookExpo America and the Combined Book Exhibit® welcome you to BookExpo America’s 1st Annual BEA New Title Showcase. We are pleased that you have taken the time to visit this new and featured exhibit. We invite you to peruse the hundreds of titles and numerous publishers on display. Many of the participating publishers also have booth space on the show floor, and their booth numbers are indicated in the show catalog. For those publishers that do not have booth space on the show floor, we have provided you with their company and other relevant information so you can contact them after the show has ended. Please take this catalog with our compliments, and keep it along with your BEA Show Directory as a record of what you saw, and whom you visited at the 2005 Show. At the conclusion of the 2005 show, this catalog will be included on the BookExpo America Web Site (bookexpoamerica.com), and Combined Book Exhibit® web site (combinedbook.com) in pdf format. Once again, thank you for visiting this exhibit, and hope you have a successful, rewarding experience at this years show. Sincerely, Chris McCabe Jon Malinowski BEA Show Director President BookExpo America Combined Book Exhibit® 383 Main Avenue 277 White Street Norwalk, CT 06851 Buchanan, NY 10511 Look for the 2nd Annual BEA New Title Showcase In Washington D.C. May 19-21, 2006 2005 BEA NEW TITLE SHOWCASE 2 Down Press, Inc. Absolute Press 12438 Moor Park St., #241 PO Box 16175 Studio City, CA 91604 Encino, CA 91416 Tel: 702-413-4373 Tel: 818-999-4419; Fax: 818-992-0091 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.aperfectswing.com Key Contact Information 1. -

A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes: Essays in Honour of Stephen A. Wild

ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD Stephen A. Wild Source: Kim Woo, 2015 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD EDITED BY KIRSTY GILLESPIE, SALLY TRELOYN AND DON NILES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A distinctive voice in the antipodes : essays in honour of Stephen A. Wild / editors: Kirsty Gillespie ; Sally Treloyn ; Don Niles. ISBN: 9781760461119 (paperback) 9781760461126 (ebook) Subjects: Wild, Stephen. Essays. Festschriften. Music--Oceania. Dance--Oceania. Aboriginal Australian--Songs and music. Other Creators/Contributors: Gillespie, Kirsty, editor. Treloyn, Sally, editor. Niles, Don, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Stephen making a presentation to Anbarra people at a rom ceremony in Canberra, 1995’ (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies). This edition © 2017 ANU Press A publication of the International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Music and Dance of Oceania. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this book contains images and names of deceased persons. Care should be taken while reading and viewing. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Foreword . xi Svanibor Pettan Preface . xv Brian Diettrich Stephen A . Wild: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes . 1 Kirsty Gillespie, Sally Treloyn, Kim Woo and Don Niles Festschrift Background and Contents . -

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Performance Studies

PERFORMANCE STUDIES The publication of Performance Studies:An Introduction was a The book itself has also been revised, with 25 new defining moment for the field. Richard Schechner’s pioneer- extracts and biographies, up-to-date coverage of global and ing textbook provides a lively and accessible overview of the intercultural performances, and further exploration of the full range of performance for undergraduates at all levels and growing international presence of performance studies as a beginning graduate students in performance studies,theatre, discipline. performing arts, and cultural studies. Among the topics Performance Studies is the definitive overview for under- discussed are the performing arts and popular entertain- graduates, with primary extracts, student activities, key ments, rituals, play and games, and the performances of biographies and over 200 images of global performance. everyday life.Supporting examples and ideas are drawn from the social sciences,performing arts,poststructuralism,ritual Richard Schechner is a pioneer of performance studies. theory,ethology,philosophy,and aesthetics. A scholar, theatre director, editor, and playwright, he is This third edition is accompanied by an all-new companion University Professor and Professor of Performance Studies at website curated by Sara Brady. It features clips of Richard the Tisch School of the Arts,NewYork University.He is editor Schechner discussing his approach to performance studies and of TDR:The Journal of Performance Studies. Schechner is the explaining key ideas, -

Zines and Minicomics Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c85t3pmt No online items Guide to the Zines and Minicomics Collection Finding Aid Authors: Anna Culbertson and Adam Burkhart. © Copyright 2014 Special Collections & University Archives. All rights reserved. 2014-05-01 5500 Campanile Dr. MC 8050 San Diego, CA, 92182-8050 URL: http://library.sdsu.edu/scua Email: [email protected] Phone: 619-594-6791 Guide to the Zines and MS-0278 1 Minicomics Collection Guide to the Zines and Minicomics Collection 1985 Special Collections & University Archives Overview of the Collection Collection Title: Zines and Minicomics Collection Dates: 1985- Bulk Dates: 1995- Identification: MS-0278 Physical Description: 42.25 linear ft Language of Materials: EnglishSpanish;Castilian Repository: Special Collections & University Archives 5500 Campanile Dr. MC 8050 San Diego, CA, 92182-8050 URL: http://library.sdsu.edu/scua Email: [email protected] Phone: 619-594-6791 Access Terms This Collection is indexed under the following controlled access subject terms. Topical Term: American poetry--20th century Anarchism Comic books, strips, etc. Feminism Gender Music Politics Popular culture Riot grrrl movement Riot grrrl movement--Periodicals Self-care, Health Transgender people Women Young women Accruals: 2002-present Conditions Governing Use: The copyright interests in these materials have not been transferred to San Diego State University. Copyright resides with the creators of materials contained in the collection or their heirs. The nature of historical archival and manuscript collections is such that copyright status may be difficult or even impossible to determine. Requests for permission to publish must be submitted to the Head of Special Collections, San Diego State University, Library and Information Access. -

Indigenous Participation in Australian Economies

Indigenous Participation in Australian Economies Historical and anthropological perspectives Indigenous Participation in Australian Economies Historical and anthropological perspectives Edited by Ian Keen THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ip_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Indigenous participation in Australian economies : historical and anthropological perspectives / edited by Ian Keen. ISBN: 9781921666865 (pbk.) 9781921666872 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Economic conditions. Business enterprises, Aboriginal Australian. Aboriginal Australians--Employment. Economic anthropology--Australia. Hunting and gathering societies--Australia. Australia--Economic conditions. Other Authors/Contributors: Keen, Ian. Dewey Number: 306.30994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: Camel ride at Karunjie Station ca. 1950, with Jack Campbell in hat. Courtesy State Library of Western Australia image number 007846D. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements. .vii List.of.figures. ix Contributors. xi 1 ..Introduction. 1 Ian Keen 2 ..The.emergence.of.Australian.settler.capitalism.in.the.. nineteenth.century.and.the.disintegration/integration.of.. Aboriginal.societies:.hybridisation.and.local.evolution.. within.the.world.market. 23 Christopher Lloyd 3 ..The.interpretation.of.Aboriginal.‘property’.on.the. -

PERFORMANCE STUDIES: an Introduction

PERFORMANCE STUDIES The publication of Performance Studies:An Introduction was a The book itself has also been revised, with 25 new defining moment for the field. Richard Schechner’s pioneer- extracts and biographies, up-to-date coverage of global and ing textbook provides a lively and accessible overview of the intercultural performances, and further exploration of the full range of performance for undergraduates at all levels and growing international presence of performance studies as a beginning graduate students in performance studies,theatre, discipline. performing arts, and cultural studies. Among the topics Performance Studies is the definitive overview for under- discussed are the performing arts and popular entertain- graduates, with primary extracts, student activities, key ments, rituals, play and games, and the performances of biographies and over 200 images of global performance. everyday life.Supporting examples and ideas are drawn from the social sciences,performing arts,poststructuralism,ritual Richard Schechner is a pioneer of performance studies. theory,ethology,philosophy,and aesthetics. A scholar, theatre director, editor, and playwright, he is This third edition is accompanied by an all-new companion University Professor and Professor of Performance Studies at website curated by Sara Brady. It features clips of Richard the Tisch School of the Arts,NewYork University.He is editor Schechner discussing his approach to performance studies and of TDR:The Journal of Performance Studies. Schechner is the explaining key ideas, -

Sing! 1975 – 2014 Song Index

Sing! 1975 – 2014 song index Song Title Composer/s Publication Year/s First line of song 24 Robbers Peter Butler 1993 Not last night but the night before ... 59th St. Bridge Song [Feelin' Groovy], The Paul Simon 1977, 1985 Slow down, you move too fast, you got to make the morning last … A Beautiful Morning Felix Cavaliere & Eddie Brigati 2010 It's a beautiful morning… A Canine Christmas Concerto Traditional/May Kay Beall 2009 On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me… A Long Straight Line G Porter & T Curtan 2006 Jack put down his lister shears to join the welders and engineers A New Day is Dawning James Masden 2012 The first rays of sun touch the ocean, the golden rays of sun touch the sea. A Wallaby in My Garden Matthew Hindson 2007 There's a wallaby in my garden… A Whole New World (Aladdin's Theme) Words by Tim Rice & music by Alan Menken 2006 I can show you the world. A Wombat on a Surfboard Louise Perdana 2014 I was sitting on the beach one day when I saw a funny figure heading my way. A.E.I.O.U. Brian Fitzgerald, additional words by Lorraine Milne 1990 I can't make my mind up- I don't know what to do. Aba Daba Honeymoon Arthur Fields & Walter Donaldson 2000 "Aba daba ... -" said the chimpie to the monk. ABC Freddie Perren, Alphonso Mizell, Berry Gordy & Deke Richards 2003 You went to school to learn girl, things you never, never knew before. Abiyoyo Traditional Bantu 1994 Abiyoyo .. -

Vignettes from a Lifetime of Studying Performance Richard Schechner

Vignettes From a Lifetime of Studying Performance Richard Schechner Abstract In this commentary, summarized from a recent interview, the author shares insights and memories from a career devoted to drama and performance studies. He enthusiastically recounts events, initiatives, and collaborations that have helped sustain his lifelong passion for performance. Prologue: New York City, April 27, 2020 There is no darkness that doesn’t have some light. It’s very nice to be in a city where there is 60 to 80% less air pollution; where the sky is clear; there is very little traffic, you can breathe. When you go out in the morning and take a walk, the streets are pretty empty, but you do this dance if somebody comes near you, you move away. The negative, of course, is that it’s a night without a clear dawn in the sense that when it gets dark tonight at 7:30 or 8:00 pm, I know that at 6:30 or 7:00 am the light will come up. I’m not sure when the light is going to come up with this pandemic. Developing a Critical Distance As I got into my late teenage years and decided to go college, I saw myself at that point as a writer and literary person. My undergraduate degree was in English and Philosophy with a lot of Psychology. I started to do lots of writing during that period. I was at Cornell University at the daily newspaper, The Cornell Daily Sun, and I wrote for it intensively. When I was a senior, I probably could have stood to be editor-in-chief, but by that time I was more reflective, so I decided to become the editorial page editor, who oversees the opinions of the paper, and also I was a drama reviewer. -

Performance Program Notes and Translations (In Program Order)

Performance Program Notes and Translations (in program order) Concert 1 Thursday, March 12, 1:30-2:30 (McCastlain Hall Fireplace Room) The Platypus Story by Stephanie Berg (1986) performed by The Platypus Players Beth Wheeler (Arkansas Symphony Orchestra), oboe; Rochelle G. Mann (Fort Lewis College), flute Tatiana R. Mann (Texas Tech University), piano Richard Wheeler (University of Arkansas Medical School), Narrator #1 Julian Mann (Elementary School), Narrator #2 The Platypus Story follows the tale of various forest creatures, each belonging to their own bird, fish or mammal group, who come across an animal that seems to defy categorization. The story is adapted from the traditional Aboriginal Australian tale, which is one of the original stories of the Dreamtime. “Dreamtime” is the Aboriginal Australian understanding of the world, its creation and the beginning of knowledge as described through a series of tales. Its wonderful message of strength of unity and beauty in diversity reflects the belief that all life as it is today is part of one vast, unchanging network of relationships that can be traced to the Creation and Great Spirit ancestors of the Dreamtime. The music chosen to accompany this tale utilizes an expanded yet familiar tonal language that is evocative, charming and quirky enough to match that strangest of animals, the platypus. Incantation and Dance by William Grant Still (1895-1978) performed by Toot Suite Tara Schwab (Arkansas State University), flute Kristin Leitterman (Arkansas State University), oboe Emily Trapp Jenkins (Arkansas State University), piano An Arkansas Son: William Grant Still (1895–1978) William Grant Still (1895-1978) was born in Mississippi and raised in Little Rock, Arkansas, where he developed his love for music and ability on numerous instruments before moving to Ohio to attend Wilberforce University and later Oberlin Conservatory.