Grey Lodge Occult Review™

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Sinister Wisdom 70.Pdf

Sinister Sinister Wisdom 70 Wisdom 70 30th Anniversary Celebration Spring 2007 $6$6 US US Publisher: Sinister Wisdom, Inc. Sinister Wisdom 70 Spring 2007 Submission Guidelines Editor: Fran Day Layout and Design: Kim P. Fusch Submissions: See page 152. Check our website at Production Assistant: Jan Shade www.sinisterwisdom.org for updates on upcoming issues. Please read the Board of Directors: Judith K. Witherow, Rose Provenzano, Joan Nestle, submission guidelines below before sending material. Susan Levinkind, Fran Day, Shaba Barnes. Submissions should be sent to the editor or guest editor of the issue. Every- Coordinator: Susan Levinkind thing else should be sent to Sinister Wisdom, POB 3252, Berkeley, CA 94703. Proofreaders: Fran Day and Sandy Tate. Web Design: Sue Lenaerts Submission Guidelines: Please read carefully. Mailing Crew for #68/69: Linda Bacci, Fran Day, Roxanna Fiamma, Submission may be in any style or form, or combination of forms. Casey Fisher, Susan Levinkind, Moire Martin, Stacee Shade, and Maximum submission: five poems, two short stories or essays, or one Sandy Tate. longer piece of up to 2500 words. We prefer that you send your work by Special thanks to: Roxanna Fiamma, Rose Provenzano, Chris Roerden, email in Word. If sent by mail, submissions must be mailed flat (not folded) Jan Shade and Jean Sirius. with your name and address on each page. We prefer you type your work Front Cover Art: “Sinister Wisdom” Photo by Tee A. Corinne (From but short legible handwritten pieces will be considered; tapes accepted the cover of Sinister Wisdom #3, 1977.) from print-impaired women. All work must be on white paper. -

Maurice Merleau-Ponty,The Visible and the Invisible

Northwestern University s t u d i e s i n Phenomenology $ Existential Philosophy GENERAL EDITOR John Wild. ASSOCIATE EDITOR James M. Edie CONSULTING EDITORS Herbert Spiegelberg William Earle George A. Schrader Maurice Natanson Paul Ricoeur Aron Gurwitsch Calvin O. Schrag The Visible and the Invisible Maurice Merleau-Ponty Edited by Claude Lefort Translated by Alphonso Lingis The Visible and the Invisible FOLLOWED BY WORKING NOTES N orthwestern U n i v e r s i t y P r e s s 1968 EVANSTON Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Originally published in French under the title Le Visible et l'invisible. Copyright © 1964 by Editions Gallimard, Paris. English translation copyright © 1968 by Northwestern University Press. First printing 1968. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 15 14 13 12 11 ISBN-13: 978-0-8101-0457-0 isbn-io: 0-8101-0457-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress Permission has been granted to quote from Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes (New York: The Philosophical Library, 1956). @ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence o f Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi Z39.48-1992. Contents Editor’s Foreword / xi Editorial Note / xxxiv T ranslatofs Preface / xl T h e Visib l e a n d t h e In v is ib l e : Philosophical Interrogation i Reflection and Interrogation / 3 a Interrogation and Dialectic / 50 3 Interrogation and Intuition / 105 4 The Intertwining—The Chiasm / 130 5 [a ppen d ix ] Preobjective Being: The Solipsist World / 156 W orking N otes / 165 Index / 377 Chronological Index to Working Notes / 279 Editor's Foreword How eve r e x p e c t e d it may sometimes be, the death of a relative or a friend opens an abyss before us. -

Performance Theory

Performance Theory “Reading Performance Theory by Richard Schechner again, three decades after its first edition, is like meeting an old friend and finding out how much of him/her has been with you all along this way.” Augusto Boal “It is an indispensable text in all aspects of the new discipline of Performance Studies. It is in many ways an eye-opener par- ticularly in its linkage of theater to other performance genres.” Ngu˜ gı˜ wa Thiong’o, University of California “Richard Schechner has defined the parameters of con- temporary performance with an originality and insight that make him indispensable to contemporary theatrical thought. For many years, both scholars and artists have been inspired by his unique and powerful perspective.” Richard Foreman “Schechner has a place in every theater history textbook for his ground-breaking work in environmental theater in the 1960s and 1970s and for his vision in helping to found the discipline of performance studies.” Rebecca Schneider “Richard Schechner is the master teacher and the master conversant on the transformative power of performance to both performer and spectator, at its deepest level. Perform- ance Theory is the essential book which brilliantly illuminates the world as a performance space on stage and off.” Anna Deveare Smith A highlands Papua New Guinea man takes a break from dancing (see chapter 4, “From ritual to theater and back: the efficacy– entertainment braid”). Richard Schechner Performance Theory Revised and expanded edition, with a new preface by the author London and New York Essays on Performance Theory published 1977 by Ralph Pine, for Drama School Specialists Second edition first published 1988 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 First published in the United Kingdom 1988 by Routledge First published in Routledge Classics 2003 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. -

Phenomenology of Perception

Copyrighted Material-Taylor & Francis Phenomenology of Perception Maurice Merleau-Ponty Copyrighted Material-Taylor & Francis Phenomenology of Perception First published in 1945, Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s monumental Phénoménologie de la perception signaled the arrival of a major new philosophical and intellectual voice in post-war Europe. Breaking with the prevailing picture of existentialism and phenom- enology at the time, it has become one of the landmark works of twentieth-century thought. This new translation, the first for over fifty years, makes this classic work of philosophy available to a new generation of readers. Phenomenology of Perception stands in the great phenomenological tradition of Hus- serl, Heidegger, and Sartre. Yet Merleau-Ponty’s contribution is decisive, as he brings this tradition and other philosophical predecessors, particularly Descartes and Kant, to confront a neglected dimension of our experience: the lived body and the phenom- enal world. Charting a bold course between the reductionism of science on the one hand and “intellectualism” on the other, Merleau-Ponty argues that we should regard the body not as a mere biological or physical unit, but as the body which structures one’s situation and experience within the world. Merleau-Ponty enriches his classic work with engaging studies of famous cases in the history of psychology and neurology as well as phenomena that continue to draw our attention, such as phantom limb syndrome, synesthesia, and hallucination. This new translation includes many helpful features such as the reintroduction of Mer- leau-Ponty’s discursive Table of Contents as subtitles into the body of the text, a com- prehensive Translator’s Introduction to its main themes, essential notes explaining key terms of translation, an extensive Index, and an important updating of Merleau-Ponty’s references to now available English translations. -

2005Newtitle 000.Pdf

The Combined ® Book Exhibit Welcome to BookExpo America 2005 Dear Industry Colleague: BookExpo America and the Combined Book Exhibit® welcome you to BookExpo America’s 1st Annual BEA New Title Showcase. We are pleased that you have taken the time to visit this new and featured exhibit. We invite you to peruse the hundreds of titles and numerous publishers on display. Many of the participating publishers also have booth space on the show floor, and their booth numbers are indicated in the show catalog. For those publishers that do not have booth space on the show floor, we have provided you with their company and other relevant information so you can contact them after the show has ended. Please take this catalog with our compliments, and keep it along with your BEA Show Directory as a record of what you saw, and whom you visited at the 2005 Show. At the conclusion of the 2005 show, this catalog will be included on the BookExpo America Web Site (bookexpoamerica.com), and Combined Book Exhibit® web site (combinedbook.com) in pdf format. Once again, thank you for visiting this exhibit, and hope you have a successful, rewarding experience at this years show. Sincerely, Chris McCabe Jon Malinowski BEA Show Director President BookExpo America Combined Book Exhibit® 383 Main Avenue 277 White Street Norwalk, CT 06851 Buchanan, NY 10511 Look for the 2nd Annual BEA New Title Showcase In Washington D.C. May 19-21, 2006 2005 BEA NEW TITLE SHOWCASE 2 Down Press, Inc. Absolute Press 12438 Moor Park St., #241 PO Box 16175 Studio City, CA 91604 Encino, CA 91416 Tel: 702-413-4373 Tel: 818-999-4419; Fax: 818-992-0091 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.aperfectswing.com Key Contact Information 1. -

A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes: Essays in Honour of Stephen A. Wild

ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD Stephen A. Wild Source: Kim Woo, 2015 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD EDITED BY KIRSTY GILLESPIE, SALLY TRELOYN AND DON NILES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A distinctive voice in the antipodes : essays in honour of Stephen A. Wild / editors: Kirsty Gillespie ; Sally Treloyn ; Don Niles. ISBN: 9781760461119 (paperback) 9781760461126 (ebook) Subjects: Wild, Stephen. Essays. Festschriften. Music--Oceania. Dance--Oceania. Aboriginal Australian--Songs and music. Other Creators/Contributors: Gillespie, Kirsty, editor. Treloyn, Sally, editor. Niles, Don, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Stephen making a presentation to Anbarra people at a rom ceremony in Canberra, 1995’ (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies). This edition © 2017 ANU Press A publication of the International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Music and Dance of Oceania. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this book contains images and names of deceased persons. Care should be taken while reading and viewing. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Foreword . xi Svanibor Pettan Preface . xv Brian Diettrich Stephen A . Wild: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes . 1 Kirsty Gillespie, Sally Treloyn, Kim Woo and Don Niles Festschrift Background and Contents . -

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

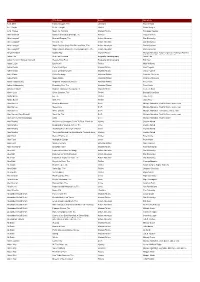

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Phenomenology of Perception

Phenomenology of Perception ‘In this text, the body-organism is linked to the world through a network of primal significations, which arise from the perception of things.’ Michel Foucault ‘We live in an age of tele-presence and virtual reality. The sciences of the mind are finally paying heed to the centrality of body and world. Everything around us drives home the intimacy of perception, action and thought. In this emerging nexus, the work of Merleau- Ponty has never been more timely, or had more to teach us ... The Phenomenology of Perception covers all the bases, from simple perception-action routines to the full Monty of conciousness, reason and the elusive self. Essential reading for anyone who cares about the embodied mind.’ Andy Clark, Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Cognitive Science Program, Indiana University Maurice Merleau-Ponty Phenomenology of Perception Translated by Colin Smith London and New York Phénomènologie de la perception published 1945 by Gallimard, Paris English edition first published 1962 by Routledge & Kegan Paul First published in Routledge Classics 2002 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor and Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1945 Editions Gallimard Translation © 1958 Routledge & Kegan Paul All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

~ Phenome Ology of Perception

~ Phenome ology ~· of Perception ~ M. MERLEAU .. PONTY Translated from the French b\ COLIN SMITH PHENOMENOLOGY OF PERCEPTION by M. Merleau-Ponty translated from the French by Colin Smith LONDON ROUTLEDGE & KEGAN PAUL NEW T O R X:: THE H UMANITIES PRESS CONTENTS Pteface page vii INTRODUCTION: TRADITIONAL PREJUDICES AND THE RETURN TO PHENOMENA 1 The 'Sensation' as a Unit of Experience 3 2 'Association' and the ' Projection of Memories' 13 3 'Attention' and 'Judgement' 26 4 The Phenomenal Field 52 PART ONE: THE BODY Experience and objective thought. The problem of the body 67 The Body as Object and Mechanistic Physiology 73 2 The Experience of the Body and Oassical Psychology 90 3 The Spatiality of One's own Body and Motility 98 4 The Synthesis of One's own Body 148 5 The Body in its SexuaJ Being 154 6 The Body as Expression, and Speech 174 PART TWO: THE WORLD AS PERCEIVED The theory of the body is already a theory of perception 203 Sense Experience 207 2 Space 243 3 The Thing and the Natural World 299 4 Other People and the Human World 346 PART THREE: BEING-FOR-ITSELF AND BEING-IN-THE-WORLD I Tho Cogito 369 2 Temporality 410 3 Freedom 434 Bibliography 457 Index 463 v PREFACE the characteristics which zoology, social anatomy or inductive psycho logy recognize in these various products of the natural or historical process- 1 am the absolute source, my existence does not stem from my antecedents, from my physical and social environment; instead it moves out towards them and sustains them, for I alone bring into being for myself (and therefore into being in the only sense that the word can have for me) the tradition which I elect to carry on, or the horizon whose distance from me would be abolished-since that distance is not one of its properties-if 1 were not there to scan it with my gaze. -

The Italian Verse of Milton May 2018

University of Nevada, Reno The Italian Verse of Milton A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Francisco Nahoe Dr James Mardock/Dissertation Advisor May 2018 © 2018 Order of Friars Minor Conventual Saint Joseph of Cupertino Province All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Francisco Nahoe entitled The Italian Verse of Milton be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY James Mardock PhD, Adviser Eric Rasmussen PhD, Committee Member Lynda Walsh PhD, Committee Member Donald Hardy PhD (emeritus), Committee Member Francesco Manca PhD (emeritus), Committee Member Jaime Leaños PhD, Graduate School Representative David Zeh PhD, Dean, Graduate School May 2018 i Abstract The Italian verse of Milton consists of but six poems: five sonnets and the single stanza of a canzone. Though later in life the poet will celebrate conjugal love in Book IV of Paradise Lost (1667) and in Sonnet XXIII Methought I saw my late espousèd saint (1673), in 1645 Milton proffers his lyric of erotic desire in the Italian language alone. His choice is both unusual and entirely fitting. How did Milton, born in Cheapside, acquire Italian at such an elevated level of proficiency? When did he write these poems and where? Is the woman about whom he speaks an historical person or is she merely the poetic trope demanded by the genre? Though relatively few critics have addressed the style of Milton’s Italian verse, an astonishing range of views has nonetheless emerged from their assessments. -

California Cosmogony Curriculum: the Legacy of James Moffett by Geoffrey Sirc and Thomas Rickert

CALIFONIA COSMOGONY CURRICULUM: THE LEGACY OF JAMES MOFFEtt GEOFFREY SIRC AND THOMAS RICKERT enculturation intermezzo • ENCULTURATION ~ INTERMEZZO • ENCULTURATION, a Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, announces the launch of Intermezzo, a series dedicated to publishing long essays – between 20,000 and 80,000 words – that are too long for journal publication, but too short to be a monograph. Intermezzo fills a current gap within scholarly writing by allowing writers to express themselves outside of the constraints of formal academic publishing. Intermezzo asks writers to not only consider a variety of topics from within and without academia, but to be creative in doing so. Authors are encouraged to experiment with form, style, content, and approach in order to break down the barrier between the scholarly and the creative. Authors are also encouraged to contribute to existing conversations and to create new ones. INTERMEZZO essays, published as ebooks, will broadly address topics of academic and general audience interest. Longform or Longreads essays have proliferated in recent years across blogs and online magazine outlets as writers create new spaces for thought. While some scholarly presses have begun to consider the extended essay as part of their overall publishing, scholarly writing, overall, still lacks enough venues for this type of writing. Intermezzo contributes to this nascent movement by providing new spaces for scholarly writing that the academic journal and monograph cannot accommodate. Essays are meant to be provocative, intelligent, and not bound to standards traditionally associated with “academic writing.” While essays may be academic regarding subject matter or audience, they are free to explore the nature of digital essay writing and the various logics associated with such writing - personal, associative, fragmentary, networked, non-linear, visual, and other rhetorical gestures not normally appreciated in traditional, academic publishing.