Sinister Wisdom 70.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conflicts in Appraising Lesbian Pulp Novels Julie Botnick IS 438A

Pulp Frictions: Conflicts in Appraising Lesbian Pulp Novels Julie Botnick IS 438A: Seminar in Archival Appraisal June 14, 2018 Abstract The years between 1950 and 1965 were the “golden age” of lesbian pulp novels, which provided some of the only representations of lesbians in the mid-20th century. Thousands of these novels sit in plastic sleeves on shelves in special collections around the United States, val- ued for their evocative covers and campy marketing language. Devoid of accompanying docu- mentation which elaborates on the affective relationships lesbians had with these novels in their own time, the pulps are appraised for their value as visual objects rather than their role in peo- ple’s lives. The appraisal decisions made around these pulps are interdependent with irreversible decisions around access, exhibition, and preservation. I propose introducing affect as an appraisal criterion to build equitable collections which reflect full, holistic life experiences. This would do better justice to the women of the past who relied on these books for survival. !1 “Deep within me the joy spread… As my whole being convulsed in ecstasy I could feel Marilyn sharing my miracle.” From These Curious Pleasures by Sloan Britain, 1961 Lesbian pulp novels provided some of the only representations of lesbians in the mid-20th century. Cheaper than a pack of gum, these ephemeral novels were enjoyed in private and passed discreetly around, stuffed under mattresses, or tossed out with the trash. Today, thou- sands of these novels sit in plastic sleeves on shelves in special collections around the United States, valued for their evocative covers and campy marketing language. -

Grey Lodge Occult Review™

May 1 2003 e.v. Issue #5 Grey Lodge Occult Review™ Gems from the Archives Selections from the archived Web-Material C O N T E N T S Mummeries of Resurrection The Cycle of Osiris in Finnegans Wake by Mark L. Troy The Man Who Invented Flying Saucers by John A. Keel SF, Occult Sciences, and Nazi Myths by Manfred Nagl Exegesis excerpts 1974-1982 "The Ten Major Principles of the Gnostic Revelation" by Philip K. Dick I Understand Philip K. Dick by Terence Mckenna Dr. Green and the Goblins of Langley by Jim Schnabel Brother Dave Morehouse D:.I:.A:. Remote Viewer & NDE Experiencer Excerpt from: Psychic Warrior by David Morehouse The Oberg Files by Blue Resonant Human, Ph.D. (Agent BlueBird) EXIT Communication to all Brethren (Information) from Robert De Grimston The Process - Church of the Final Judgement The Gitanjali or `song offerings' by Rabindranath Tagore with an introduction by William B. Yeats Rosa Alchemica by William B. Yeats (Note: PDF) John Dee by Charlotte Fell-Smith (Note: PDF) Serapis A Romance by Georg Ebers (Note: PDF) Home GLORidx Close Window Except where otherwise noted, Grey Lodge Occult Review™ is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. Grey Lodge Occult Review™ 2003 e.v. - Issue #5 Mummeries of Resurrection The Cycle of Osiris in Finnegans Wake Mark L. Troy Uppsala 1976 Doctoral dissertation at the University of Uppsala 1976 HTML version prepared by Eric Rosenbloom Kirby Mountain Composition & Graphics 2002 Note: Page numbers from the printed text have been retained in the table of contents to use as approximate guides for the references in the bibliographies, line index, and elsewhere. -

Feminist Periodicals

The Un vers ty of W scons n System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 26, Number 4, Winter 2007 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents Volume 26, Number 4 (Winter 2007) Periodical literature is the cutting edge ofwomen's scholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table of contents pages from current issues ofmajorfeministjournalsare reproduced in each issue ofFeminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the follOWing information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of pUblication. 3. Subscription prices (print only; for online prices, consult publisher). 4. Subscription address. -

Cultivating the Daughters of Bilitis Lesbian Identity, 1955-1975

“WHAT A GORGEOUS DYKE!”: CULTIVATING THE DAUGHTERS OF BILITIS LESBIAN IDENTITY, 1955-1975 By Mary S. DePeder A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History Middle Tennessee State University December 2018 Thesis Committee: Dr. Susan Myers-Shirk, Chair Dr. Kelly A. Kolar ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I began my master’s program rigidly opposed to writing a thesis. Who in their right mind would put themselves through such insanity, I often wondered when speaking with fellow graduate students pursuing such a goal. I realize now, that to commit to such a task, is to succumb to a wild obsession. After completing the paper assignment for my Historical Research and Writing class, I was in far too deep to ever turn back. In this section, I would like to extend my deepest thanks to the following individuals who followed me through this obsession and made sure I came out on the other side. First, I need to thank fellow history graduate student, Ricky Pugh, for his remarkable sleuthing skills in tracking down invaluable issues of The Ladder and Sisters. His assistance saved this project in more ways than I can list. Thank-you to my second reader, Dr. Kelly Kolar, whose sharp humor and unyielding encouragement assisted me not only through this thesis process, but throughout my entire graduate school experience. To Dr. Susan Myers- Shirk, who painstakingly wielded this project from its earliest stage as a paper for her Historical Research and Writing class to the final product it is now, I am eternally grateful. -

Beyond Trashiness: the Sexual Language of 1970S Feminist Fiction

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 4 Issue 2 Harvesting our Strengths: Third Wave Article 2 Feminism and Women’s Studies Apr-2003 Beyond Trashiness: The exS ual Language of 1970s Feminist Fiction Meryl Altman Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Altman, Meryl (2003). Beyond Trashiness: The exS ual Language of 1970s Feminist Fiction. Journal of International Women's Studies, 4(2), 7-19. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol4/iss2/2 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2003 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Beyond Trashiness: The Sexual Language of 1970s Feminist Fiction By Meryl Altmani Abstract It is now commonplace to study the beginning of second wave US radical feminism as the history of a few important groups – mostly located in New York, Boston and Chicago – and the canon of a few influential polemical texts and anthologies. But how did feminism become a mass movement? To answer this question, we need to look also to popular mass-market forms that may have been less ideologically “pure” but that nonetheless carried the edge of feminist revolutionary thought into millions of homes. This article examines novels by Alix Kates Shulman, Marge Piercy and Erica Jong, all published in the early 1970s. -

The House That Jill Built: a Lesbian Nation in Formation

THE HOUSE THAT JILL was the co-founding of the lesbian Told in the context of a number of BUILT: A LESBIAN rock band Mama Quilla 11. Indeed, crucial political developments of the many of us suspected that the best time-the bust of the Body Politic for NATION IN part of lesbian organizing was-you publishing the article "Men Loving FORMATION guessed it-the dances. Boys Loving Men," the arrival of anti- Which is to say that we panelists gay activist Anita Bryant to Toronto, Be& L. Ross. Toronto: University got the lesbian-feminist part ofit, but among them-and dropping the of Toronto Press, 1995. the "ism" was far more elusive. names ofpracticallyevery activist who Here's where Becki Ross's new drew a breath inside 342 Jarvis, The book, The House That Jill Built, is House ThatJillBuilt helps to tease out extremely usehl. It will no doubt the differences between political Recently, the Toronto Historical suffer from the no-win situation syn- streams in the '70s while respecting Board was the site of a panel on les- drome that goes with producing a the commitmentandenergy ofwomen bian feminism in the '70s as part of first book on a neglected subject-it who were charting new territory. the Pass It On series of events uncov- cannot be all things to all people. But But don't for a second conhse this ering gay and lesbian history. I and it does grapple with the problem of bookwith history. Activists oftheday two other long-time activists partici- defining lesbian feminism-not as had multiple political affiliations and pated in a spirited discussion that abstract, but as a lived politic. -

Vancouver by Tina Gianoulis

Vancouver by Tina Gianoulis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Cosmopolitan Vancouver, nestled on Canada's west coast in a picturesque triangle between English Bay, Burrard Inlet, and the Fraser River, has developed in less than 200 years from a frontier outpost in an untamed land to one of the fastest-growing cities in North America. With a constant influx of immigrants and a vigorous and adaptable economy, Vancouver is a progressive city with a large and active queer community. That community began organizing in the 1960s, with the founding of Canada's first homophile organization, and has continued into the 2000s, as activists work to protect queer rights and develop queer culture. With its sheltered location, fertile farmland, and rich inland waterways, the southwestern corner of British Columbia's mainland attracted settlers from a variety of native cultures for over three thousand years. More than twenty tribes, including the Tsawwassen and Musqueam, comprised the Stó:lo Nation, the "People of the Water," who farmed and fished the Fraser River Valley before the arrival of European explorers in the late eighteenth century. From the first European trading post, established by the Hudson Bay Company in 1827, the small community soon grew into a boomtown with a thriving economy based on its lumber and mining industries, fisheries, and agriculture. By the late 1800s, the settlement had become a hub for a newly developing railroad network, and in 1886, the City of Vancouver was incorporated. The city grew rapidly, tripling its population within a few decades and spawning a construction boom in the early 1900s. -

True Colors Resource Guide

bois M gender-neutral M t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bois bois gender-neutral M gender-neutralLOVEM gender-neutral t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch Birls polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme Asexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious transsexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual bois M gender-neutral gender-neutral M t t F F ALLY Lesbian INTERSEX butch INTERSEXALLY Birls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer bisexual Asexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual bi-curious bi-curious transsexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bois bois LOVE gender-neutral M gender-neutral t F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual bois bois M gender-neutral M gender-neutral t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident -

Stockholm Cinema Studies 11

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Cinema Studies 11 Imagining Safe Space The Politics of Queer, Feminist and Lesbian Pornography Ingrid Ryberg This is a print on demand publication distributed by Stockholm University Library www.sub.su.se First issue printed by US-AB 2012 ©Ingrid Ryberg and Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis 2012 ISSN 1653-4859 ISBN 978-91-86071-83-7 Publisher: Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, Stockholm Distributor: Stockholm University Library, Sweden Printed 2012 by US-AB Cover image: Still from Phone Fuck (Ingrid Ryberg, 2009) Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................... 13 Research aims and questions .................................................................................... 13 Queer, feminist and lesbian porn film culture: central debates.................................... 19 Feminism and/vs. pornography ............................................................................. 20 What is queer, feminist and lesbian pornography?................................................ 25 The sexualized public sphere................................................................................ 27 Interpretive community as a key concept and theoretical framework.......................... 30 Spectatorial practices and historical context.......................................................... 33 Porn studies .......................................................................................................... 35 Embodied -

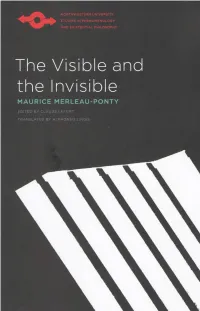

Maurice Merleau-Ponty,The Visible and the Invisible

Northwestern University s t u d i e s i n Phenomenology $ Existential Philosophy GENERAL EDITOR John Wild. ASSOCIATE EDITOR James M. Edie CONSULTING EDITORS Herbert Spiegelberg William Earle George A. Schrader Maurice Natanson Paul Ricoeur Aron Gurwitsch Calvin O. Schrag The Visible and the Invisible Maurice Merleau-Ponty Edited by Claude Lefort Translated by Alphonso Lingis The Visible and the Invisible FOLLOWED BY WORKING NOTES N orthwestern U n i v e r s i t y P r e s s 1968 EVANSTON Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Originally published in French under the title Le Visible et l'invisible. Copyright © 1964 by Editions Gallimard, Paris. English translation copyright © 1968 by Northwestern University Press. First printing 1968. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 15 14 13 12 11 ISBN-13: 978-0-8101-0457-0 isbn-io: 0-8101-0457-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress Permission has been granted to quote from Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes (New York: The Philosophical Library, 1956). @ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence o f Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi Z39.48-1992. Contents Editor’s Foreword / xi Editorial Note / xxxiv T ranslatofs Preface / xl T h e Visib l e a n d t h e In v is ib l e : Philosophical Interrogation i Reflection and Interrogation / 3 a Interrogation and Dialectic / 50 3 Interrogation and Intuition / 105 4 The Intertwining—The Chiasm / 130 5 [a ppen d ix ] Preobjective Being: The Solipsist World / 156 W orking N otes / 165 Index / 377 Chronological Index to Working Notes / 279 Editor's Foreword How eve r e x p e c t e d it may sometimes be, the death of a relative or a friend opens an abyss before us. -

For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism Kelly Anderson Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/8 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] For Love and For Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism By Kelly Anderson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The Graduate Center, City University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History 2014 © 2014 KELLY ANDERSON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Blanche Wiesen Cook Chair of Examining Committee Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Bonnie Anderson Bettina Aptheker Gerald Markowitz Barbara Welter Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism By Kelly Anderson Adviser: Professor Blanche Wiesen Cook This dissertation explores the role of lesbians in the U.S. second wave feminist movement, arguing that the history of women’s liberation is more diverse, more intersectional, -

Lines on Lesbian Sex the Politics of Representing Lesbian Sex in the Age of Ms

Lines on Lesbian Sex The Politics of Representing Lesbian Sex in the Age of ms by Gabrich Grpn heterosexuality) that such material, especially anything considered pornographic, fragments the erotic and the emotional-utilizes the imbrication of the emotional in Cetarticksurks rcprCsrntation.rpornographiques/krotiqucs the sexual as part of its construction. This acts as a lcsbiennes au temps du MH/SIDA dhnontre, entw aum, h palliative for the more problematic aspects of the material. Tmicallv,.* . Pat Califia for instance, an inlfamous producer of sadomasochistic material, writes in one of her stories: Even when correcting serious misdeeds, Berenice Women are manibukzted1 into heterosexualitvr' [dominatrix and moier] was not brutal. She loved through a discourse which exploits and helplessness, she craved the sight of a female body re-directs their emotional need away from abandoningalldecency and self-control. These things the female and to the male. are not granted save in loving trust. Dominance is not J created without complicity. A well-trained slave is hopelessly in love with her mistress.. .. (67) conjiuion qui rlgnr &ns &S communautishbiennes lorsque This story, centring on a sadomasochistic mother- virnt k temps d'aborder k nrjet du MH/SIDA. daughter relationship and recuperativeofthe primary love relationship between female carer and dependent inht Lesbian erotic, or if you like, pornographic1 postulated by psychoanalysis, presents a whole series of (re)presentationfrequently bases the quest for the, or an, incest-taboo-breaking