Economic Inequality and Institutional Adaptation in Response to Flood Hazards: a Historical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunsotron Informatieblad Voor De Radio- En Zendamateurs Van De Veron Afdeling Hunsingo – A60

HUNSOTRON INFORMATIEBLAD VOOR DE RADIO- EN ZENDAMATEURS VAN DE VERON AFDELING HUNSINGO – A60 Derk Bosscher van Radio Noord in gesprek met Peter (PA40) en Tjip (PD2TW). Zie artikel van de CQWW SSB contest@PA6GR 2016 6e jaargang – nummer 4 – december 2016 Colofon Hunsotron is het orgaan van de Veron afdeling Hunsingo. Het verschijnt vier maal per jaar en wordt in PDF-formaat aan de leden van de afde- QSL-service ling gemaild. En aan belangstellenden die zich sub-QSL-manager: daarvoor hebben aangemeld. De verschenen Free Abbing, PE1DUG. nummers van Hunsotron staan ook op de website Het koffertje met de binnengekomen QSL- van de afdeling: http://a60.veron.nl/. Overname kaarten is bij alle afdelingsactiviteiten aanwezig. van artikelen met bronvermelding is toegestaan. Komt u niet naar de afdelingsavond(en), vraag dan of een mede-amateur uw kaarten wil Redactie meenemen. Is dat niet mogelijk, neem dan eindredactie: contact op met de manager om iets anders af te Pieter Kluit, NL13637. spreken. Desgewenst kunnen de voor u redactielid/webmaster: bestemde kaarten (op uw kosten) per post Bas Levering, PE4BAS. worden toegestuurd. Binnengekomen QSL- Kopij voor de Hunsotron kunt u sturen naar: kaarten blijven één jaar in de koffer. Zijn de [email protected] kaarten daarna nog niet afgehaald, dan worden Afdelingsbestuur ze naar de afzenders teruggestuurd met de voorzitter: vermelding “not interested”. Dick van den Berg, PA2DTA, Baron van Asbeckweg 6, 9963PC Warfhuizen, tel. 0595- 572066. secretaris: Free Abbing, PE1DUG, Nijenoertweg 129, 9351HR Leek, tel. 0594-853048, e-mail: [email protected] penningmeester: Hans Reijn, PA3GTM, Wilhelminastraat 12, 9965PP Leens, tel. -

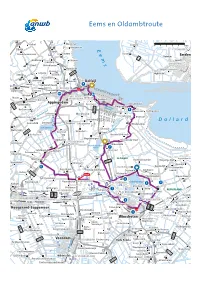

Eems En Oldambtroute

Eems en Oldambtroute Tweehuizen Nieuwstad Kolhol Loquard 0 1 2 3 4 5 km Hoogwatum Zijldijk E e m s 2 PEWSUM Spijk 't Zandstervoorwerk Bierum Rysum Twixlum Emden Godlinze Uiteinde L2 Larrelt Losdorp EMDEN-WEST 't Zandt Oldenklooster Holwierde Logumer Vorwerk Krewerd Lutjerijp Wybelsum Zeerijp Arwerd N997 Nijenklooster Leermens Jukwerd Marsum Delfzijl Eenum Oosterwijtwerd 9 DELFZIJL Loppersum Eekwerd Tjamsweer 10 Wirdum Merum Farmsum Garreweer APPINGEDAM Weiwerd Enzelens Appingedam N360 Garrelsweer Amsweer Geefsweer Zeehaven- Termunterzijl kanaal Borgsweer Hoeksmeer 8 N362 Wartumerklap Termunten Dallingeweer Laskwerd Meedhuizen Wittewierum Eemskanaal Lalleweer Baamsum Opmeeden p ie Dollard ld Steendam ij Overschild Tjuchem Schaapbulten z r Woldendorp te n Schildmeer Zomerdijk u Woltersum Wilderhof rm Geerland Kopaf Te N865 De Paauwen Oostwolderhamrik Wagenborgen Siddeburen Nieuwolda-Oost SIDDEBUREN Luddeweer Nieuwolda Hondshalster- meer 7 Schildwolde Hellum Westeind Denemarken Schaaphok 't Waar OLDAMBT Kostverloren Slochteren Oostwolderpolder Hongerige Wolf Woudbloem Korengarst N362 Oudedijk Ganzedijk 11 Oostwold Airport Finsterwolder- Noordbroek Nieuw Scheemda Oostwold Goldhoorn hamrik Ruiten N387 start Midwolda Finsterwolde Nieuw Beerta Stootshorn 6 Froombosch Noordbroek NOORDBROEK Oldambtmeer 4 Kolham 45 SCHEEMDA 5 Meerland Spitsbergen Uiterburen 1 Ekamp 40 FOXHOL Scheemda REIDERLAND Sappemeer-Noord 43 ZUIDBROEK Beerta terdiep 46 HEILIGERLEE Winscho Blauwestad A7 Hamdijk E22 ZUIDBROEK Ulsda 41 HOOGEZAND 42 SAPPEMEER Zuidbroek 47 WINSCHOTEN -

Old Frisian, an Introduction To

An Introduction to Old Frisian An Introduction to Old Frisian History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. University of Leiden John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bremmer, Rolf H. (Rolf Hendrik), 1950- An introduction to Old Frisian : history, grammar, reader, glossary / Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Frisian language--To 1500--Grammar. 2. Frisian language--To 1500--History. 3. Frisian language--To 1550--Texts. I. Title. PF1421.B74 2009 439’.2--dc22 2008045390 isbn 978 90 272 3255 7 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 3256 4 (Pb; alk. paper) © 2009 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlands John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 · usa Table of contents Preface ix chapter i History: The when, where and what of Old Frisian 1 The Frisians. A short history (§§1–8); Texts and manuscripts (§§9–14); Language (§§15–18); The scope of Old Frisian studies (§§19–21) chapter ii Phonology: The sounds of Old Frisian 21 A. Introductory remarks (§§22–27): Spelling and pronunciation (§§22–23); Axioms and method (§§24–25); West Germanic vowel inventory (§26); A common West Germanic sound-change: gemination (§27) B. -

Gebruikte Literatuur Januari 2009

Bijlage 5: Gebruikte literatuur Januari 2009 Literatuur-/bronnenlijst Toekomstvisie Provincie Groningen Landelijk Programma Landelijk Gebied Groningen Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke (PLG) 2007-2013 Ordening en Milieubeheer (VROM) December 2006 Nota mensen, wensen, wonen; wonen in de 21ste eeuw Provincie Groningen November 2000 Provinciaal Omgevingsplan Groningen (POP) 2009-2013 Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Juni 2009 Ordening en Milieubeheer (VROM) Nota Ruimte: Ruimte voor ontwikkeling Provincie Groningen April 2004 Sociale Agenda 2009-2012 November 2008 Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid (SZW) Provincie Groningen Actieprogramma: iedereen doet mee Sportnota Provincie Groningen 2007-2010: Oktober 2007 Mitdoun=Goud Maart 2006 Provinciaal/ regionaal Bureau PAU (i.o.v. Provincie Groningen) Streekraad Oost-Groningen Inventarisatie stedelijke vernieuwingsopgaven Energiek met Energie! in de provincie Groningen (ISV-3) 2010-2019 Maart 2009 April 2008 Stuurgroep Regioprogramma Oost Etin Adviseurs Landschapsontwikkelingsplan Oldambt, Regionaal-economische visie Oost-Groningen Westerwolde en Veenkoloniën (LOP) 2007 Maart 2006 LEADER Actiegroep Oost-Groningen Stuurgroep Regioprogramma Oost LEADER Actieplan 2007-2013 Regioprogramma Oost 2008-2011 29 mei 2007 Juni 2008 Provincie Groningen Oldambt (3 gemeenten gezamenlijk) Actieprogramma Arbeidsmarkt Oost- BügelHajema Adviseurs (i.o.v.Gemeenten Groningen 2008-2013 Reiderland, Scheemda en Winschoten) 2007 Kadernota bestemmingsplan buitengebied Juli 2008 Provincie -

The Evolution of the Money Standard in Medieval Frisia. a Treatise on the History of the Systems of Money of Account in the Former Frisia (C.600–C.1500)1

The Evolution of the Money Standard in Medieval Frisia. A treatise on the history of the systems of money of account in the former Frisia (c.600–c.1500)1 By Dirk Jan Henstra (Groningen) In august 2000, the president of the International Monetary Fund, Horst Köhler, confessed openly to representatives of the international press in Washington that, until recently, the IMF had made mistakes by underestimating ('like everyone else') the importance of institutions for building up the economies of underdeveloped countries. His statement marks the breakthrough of a new view in economics. New views in economics happen to reflect contemporary economic conditions. In this case it concerns the fundamental role of economic institutions in any economy. Köhler had to admit that indeed the emergence of economic institutions takes time. Hence the world faces another prob- lem. We have to investigate how economic institutions evolve. This article resumes the results of historical research in the evolution of an economic institu- tion over nine centuries. The institution involved is an informal institution or convention.2 It illustrates that this evolution was inevitably path-dependent. The implication is, that history matters. The history of economic institutions is to be viewed as a constituent part of the history of a culture. Essentially, economic institutions are rules for interactive economic behaviour ingrained in the minds of the members of a society, they are integrated in their culture.3 Therefore, the ques- tion may be put in what degree social engineering can shape economic institutions. There is a revival of the concept of economic institutions in the study of economics in the last decades, after a period of slumber since the Austrian School.4 Nowadays, however, economists often fo- cus on assumed logical systems behind the rules. -

Supplement of Storm Xaver Over Europe in December 2013: Overview of Energy Impacts and North Sea Events

Supplement of Adv. Geosci., 54, 137–147, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-54-137-2020-supplement © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Supplement of Storm Xaver over Europe in December 2013: Overview of energy impacts and North Sea events Anthony James Kettle Correspondence to: Anthony James Kettle ([email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC BY 4.0 License. SECTION I. Supplement figures Figure S1. Wind speed (10 minute average, adjusted to 10 m height) and wind direction on 5 Dec. 2013 at 18:00 GMT for selected station records in the National Climate Data Center (NCDC) database. Figure S2. Maximum significant wave height for the 5–6 Dec. 2013. The data has been compiled from CEFAS-Wavenet (wavenet.cefas.co.uk) for the UK sector, from time series diagrams from the website of the Bundesamt für Seeschifffahrt und Hydrolographie (BSH) for German sites, from time series data from Denmark's Kystdirektoratet website (https://kyst.dk/soeterritoriet/maalinger-og-data/), from RWS (2014) for three Netherlands stations, and from time series diagrams from the MIROS monthly data reports for the Norwegian platforms of Draugen, Ekofisk, Gullfaks, Heidrun, Norne, Ormen Lange, Sleipner, and Troll. Figure S3. Thematic map of energy impacts by Storm Xaver on 5–6 Dec. 2013. The platform identifiers are: BU Buchan Alpha, EK Ekofisk, VA? Valhall, The wind turbine accident letter identifiers are: B blade damage, L lightning strike, T tower collapse, X? 'exploded'. The numbers are the number of customers (households and businesses) without power at some point during the storm. -

Province House

The Province House SEAT OF PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT Colophon Production and final editing: Province of Groningen Photographs: Alex Wiersma and Jur Bosboom (Province of Groningen), Rien Linthout and Jenne Hoekstra Provincie Groningen Postbus 610 • 9700 AP Groningen +31 (0)50 - 316 41 60 www.provinciegroningen.nl [email protected] 2020 The Province House Seat of Provincial Government PREFACE The present and the past connected with each other. That is how you could describe the Groningen Province House. No. 12 Martinikerkhof is the ‘old’ Province House, which houses the State Hall where the Provincial Council has met since 16 June 1602. That is unique for the Netherlands. No other province has used the same assembly hall for so long. The connection with the present is formed by the aerial bridge to the ‘new’ Province House. This section of the Province House was designed by the architect Mels Crouwel and was opened on 7 May 1996 by Queen Beatrix. Both buildings have their own ambiance, their own history and their own works of art. The painting ‘Religion and Freedom’ by Hermannus Collenius (1650-1723) hangs in the State Hall and paintings by the artistic movement De Ploeg are in the building on the Martinikerkhof. The new section features work by contemporary artists such as Rebecca Horn. Her ‘The ballet of the viewers’ hangs in the hall. The binoculars observe the entrance hall and look out, through the transparent façades, to the outside world. But there is a lot more to see. And this brochure tells you everything about the past and present of the Province House. -

Et Oldambt Een Sociografie Deel I Vormende Krachten

ET OLDAMBT EEN SOCIOGRAFIE DEEL I VORMENDE KRACHTEN ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DEN GRAAD VAN DOCTOR IN DE LETTEREN EN WIJSBEGEERTE AAN DE UNIVERSITEIT VAN AMSTERDAM, OP GEZAG VAN DEN RECTOR-MAGNIFICUS Dr. E.LAQUEUR , HOOG LEERAAR IN DE FACULTEIT DER GENEESKUNDE, IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN IN DE AULA DER UNIVERSITEIT, OP DONDERDAG 8 JULI 1937, DES NAMIDDAGS TE 4 UUR PRECÏES, DOOR EVERT WILLEM HOFSTEE GEBOREN TE WESTEREMDEN BIJ J. B. WOLTERS' UITGEVERS-MAATSCHAPPIJ N.V. GRONINGEN - BATAVIA ~ 1937 CENTRAI F I AMnprvi »«^.-r 1 Aan mijn ouders Aan mijn broers en zusters r Nu ik met de voltooiing van dit proefschrift mijn universitaire studie hebbeëindigd , ishe tm eee nbehoefte , mijn dank te betuigen aan allen, wier onderwijs ikhe bmoge n volgen, Prof. Mr.Dr .W . A. Bonger, Prof. Dr. H. Brugmans, Prof. Mr. Dr. N. W. Posthumus, Prof. Mr. Dr. S. R. Steinmetz en Dr. W. van Bemmelen; in het bizonder aanmij n hooggeachten promotor, Prof.Dr .H .N . terVeen . &*•• Het doet mij leed, dat een mijner docenten — Prof. J. C. van Eerde— reed snie tmee r totd elevende n behoort. Zijn nagedachtenis zal bij miji n ere blijven. Allen in het Oldambt, landbouwers, medici, predikanten, onder wijzers envel e anderen, diemi j door hunschriftelijk e en mondelinge inlichtingen onmisbaar materiaal hebben verschaft, ben ik zeer erkentelijk. Een woord vanhartelijk e dankbe ni kverschuldig d aanProf . Mr. A. S. de Blécourt, hoogleraar aan de Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden, voor de vriendelijke belangstelling, die hij voor enkele onderdelen van mijn werk betoonde. •«m INHOUD VAN HET EERSTE DEEL. -

Gronings De Boekhandels Met

Taal in, stad* ttv UuUL GRONINGS DE BOEKHANDELS MET Academische Boekhandel, Maastricht Broese, Utrecht Dekker v.d. Vegt, Arnhem/Nijmegen/Sittard Donner, Rotterdam Gianotten, Tilburg en Breda Kooyker, Leiden Van Piere, Eindhoven Scheltema, Amsterdam Scholtens Wristers, Groningen De Tille, Leeuwarden en Sneek Verwijs, Den Haag vvTvw.boekenmeer.nl Taal uv stad wi Luid GRONINGS Siemon Reker Sdu Uitgevers, Den Haag Verschenen in de reeks 'Taal in stad en land', hoofdredactie Nicoline van der Sijs: 1 Amsterdams door Jan Berns m.m.v. Jolanda van den Braak 2 Fries en Stadsfries door Pieter Duijff 3 Gronings door Siemon Reker 4 Haags door Michael Elias i.s.m. Ton Goeman 5 Leids door Dick Wortel 6 Maastrichts door Ben Salemans en Flor Aarts 7 Oost-Brabants door Jos Swanenberg en Cor Swanenberg 8 Rotterdams door Marc van Oostendorp 9 Stellingwerfs door Henk Bloemhoff 10 Utrechts, Veluws en Flevolands door Harrie Scholtmeijer 11 Venloos, Roermonds en Sittards door Pierre Bakkes 12 West-Brabants door Hans Heestermans en Jan Stroop 13 Zuid-Gelderse dialecten door Jan Berns Vormgeving omslag en binnenwerk: Villa Y (André Klijssen), Den Haag Zetwerk: PROgrafici, Goes Druk en afwerking: A-D Druk BV, Zeist © Siemon Reker, 2002 Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestem• ming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher. ISBN 90 1209012 1 Voorwoord bij d&> reeks 'Taal Uv stad etv Uwid' De reeks Taal in stad en land is totstandgekomen op initiatief van Sdu Uitge• vers en de Boekhandels Groep Nederland (BGN). -

Gemeente Oldambt Bestemmingsplan Finsterwolde, Drieborg, Ganzedijk/Hongerige Wolf

Gemeente Oldambt Bestemmingsplan Finsterwolde, Drieborg, Ganzedijk/Hongerige Wolf Vastgesteld Bestemmingsplan Finsterwolde, Drieborg, Ganzedijk/Hongerige Wolf Code 12-62-04 / 26-06-13 GEMEENTE OLDAMBT 126204 / 26-06-13 BESTEMMINGSPLAN FINSTERWOLDE, DRIEBORG, GANZEDIJK/- HONGERIGE WOLF TOELICHTING INHOUDSOPGAVE blz 1. INLEIDING 1 1. 1. Nieuw bestemmingsplan Finsterwolde, Drieborg, Ganzedijk/Hongerige Wolf 1 1. 2. Wet ruimtelijke ordening-2008 1 1. 3. Plangebied 1 1. 4. Inhoud toelichting 1 2. BELEIDSKADER 2 2. 1. Provinciaal beleid 2 2. 2. Gemeentelijk beleid 3 3. HUIDIGE SITUATIE 5 3. 1. Ruimtelijk-historisch ontstaan en kenmerken 5 3. 2. Cultuurhistorie 8 3. 3. Functionele structuur 10 4. PLANUITGANGSPUNTEN 15 4. 1. De gewenste ruimtelijke structuur 15 4. 2. De gewenste functioneel-ruimtelijke structuur 15 4. 3. Wonen 15 4. 4. Bedrijvigheid 17 4. 5. Voorzieningen en leefbaarheid 18 4. 6. Verkeer 19 4. 7. Groen en recreatie 19 5. OMGEVINGSASPECTEN EN RANDVOORWAARDEN 20 5. 1. Water 20 5. 2. Milieu - geluid 21 5. 3. Bodem 22 5. 4. Externe Veiligheid 22 5. 5. Luchtkwaliteit 24 5. 6. Ecologie 25 5. 7. Cultuurhistorie en archeologie 26 5. 8. Duurzaamheid en energie 27 6. TOELICHTING OP DE BESTEMMINGEN 28 6. 1. Opzet van het bestemmingsplan 28 6. 2. SVBP 2008 28 6. 3. Wet ruimtelijke ordening-2008 / Wabo 2010 28 6. 4. Toelichting op de bestemmingen 29 7. UITVOERBAARHEID 35 7. 1. Maatschappelijke uitvoerbaarheid 35 7. 2. Economische uitvoerbaarheid 35 7. 3. Grondexploitatie 35 8. INSPRAAK EN OVERLEG 36 BIJLAGEN Bijlage 1 Advies Steunpunt Externe veiligheid Bijlage 2 Advies Brandweer Regio Groningen Bijlage 3 Nota inspraak- en overlegreacties 126204 blz 1 1. -

Statistical Yearbook of the Netherlands 2004

Statistical Yearbook of the Netherlands 2004 Statistics Netherlands Preface Statistics Netherlands has a long tradition in the publication of annual figures and yearbooks. The Statistical Yearbook has been the most popular publication by Statistics Netherlands for decades. This latest edition again provides facts and figures on virtually all aspects of Dutch society. It is an invaluable resource for a quick exploration of the economy, population issues, education, health care, crime, culture, the environment, housing, and many other topics. This year’s volume is structured in exactly the same way as last year. It contains the data available at the end of November 2003. For current updates please check the Statline Database at Statistics Netherlands, which is in the process of being translated into English. It can be accessed free of charge at www.cbs.nl. G. van der Veen Director General of Statistics Voorburg / Heerlen, April 2004 Preface Statistical Yearbook 2004 3 Published by Explanation of symbols Statistics Netherlands Prinses Beatrixlaan 428 . = figure not available 2273 XZ Voorburg * = provisional figure The Netherlands x = publication prohibited (confidential figure) Lay out – = nil Statistics Netherlands 0 (0.0) = less than half of unit concerned Facility services department blank = not applicable < = fewer / less / smaller than > = more / greater than Cover design ≤ = fewer / less / smaller than or equal to WAT ontwerpers (Utrecht) ≥ = more / greater than or equal to 2003-2004 = 2003 to 2004 inclusive Print 2003/2004 = average of 2003 up to and Opmeer | De Bink | TDS v.o.f., The Hague including 2004 2003/’04 = crop year, financial year, school Translation year etc. beginning in 2003 and Statistics Netherlands ending in 2004 Rita Gircour Due to rounding, some totals may not correspond with Information the sum of the separate figures E-mail [email protected] How to order Obtainable from The Sdu publishers P.O. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com07/06/2021 12:38:50PM Via Koninklijke Bibliotheek Library of the Written Word

Print and Power in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800) Nina Lamal, Jamie Cumby, and Helmer J. Helmers - 978-90-04-44889-6 Downloaded from Brill.com07/06/2021 12:38:50PM via Koninklijke Bibliotheek Library of the Written Word volume 92 The Handpress World Editor-in-Chief Andrew Pettegree (University of St Andrews) Editorial Board Ann Blair (Harvard University) Falk Eisermann (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preuβischer Kulturbesitz) Shanti Graheli (University of Glasgow) Earle Havens (Johns Hopkins University) Ian Maclean (All Souls College, Oxford) Alicia Montoya (Radboud University) Angela Nuovo (University of Milan) Helen Smith (University of York) Mark Towsey (University of Liverpool) Malcolm Walsby (ENSSIB, Lyon) Arthur der Weduwen (University of St Andrews) volume 73 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/lww Nina Lamal, Jamie Cumby, and Helmer J. Helmers - 978-90-04-44889-6 Downloaded from Brill.com07/06/2021 12:38:50PM via Koninklijke Bibliotheek Print and Power in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800) Edited by Nina Lamal Jamie Cumby Helmer J. Helmers LEIDEN | BOSTON Nina Lamal, Jamie Cumby, and Helmer J. Helmers - 978-90-04-44889-6 Downloaded from Brill.com07/06/2021 12:38:50PM via Koninklijke Bibliotheek This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material.