Cloud-Spotting Game Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Modeling of Contrail and Contrail Cirrus Climate Impact

GLOBAL MODELING OF THE CONTRAIL AND CONTRAIL CIRRUS CLIMATE IMPACT BY ULRIKE BU RKHARDT , BERND KÄRCHER , AND ULRICH SCH U MANN et al. 2010). For the given ambient Modeling the physical processes governing the life cycle of conditions, their direct radia- contrail cirrus clouds will substantially narrow the uncer- tive effect is mainly determined tainty associated with the aviation climate impact. by coverage and optical depth. The microphysical properties of contrail cirrus likely differ from substantial part of the aviation climate impact those of most natural cirrus, at least during the initial may be due to aviation-induced cloudiness (AIC; stages of the contrail cirrus life cycle (Heymsfield A Brasseur and Gupta 2010), which is arguably et al. 2010). Contrails form and persist in air that is the most important but least understood component ice saturated, whereas natural cirrus usually requires in aviation climate impact assessments. The AIC in- high ice supersaturation to form (Jensen et al. 2001). cludes contrail cirrus and changes in cirrus properties This difference implies that in a substantial fraction or occurrence arising from aircraft soot emissions of the upper troposphere contrail cirrus can persist in (soot cirrus). Linear contrails are line-shaped ice supersaturated air that is cloud free, thus increasing clouds that form behind cruising aircraft in clear air high cloud coverage. Contrails and contrail cirrus and within cirrus clouds. Linear contrails transform existing above, below, or within clouds change the into irregularly shaped ice clouds (contrail cirrus) and column optical depth and radiative fluxes. They may may form cloud clusters in favorable meteorological also indirectly affect radiation by changing the mois- conditions, occasionally covering large horizontal ture budget of the upper troposphere, and therefore areas extending up to 100,000 km2 (Duda et al. -

Contrail-Cirrus and Their Potential for Regional Climate Change

Contrail-Cirrus and Their Potential for Regional Climate Change Kenneth Sassen Department of Meteorology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah ABSTRACT After reviewing the indirect evidence for the regional climatic impact of contrail-generated cirrus clouds (contrail- cirrus), the author presents a variety of new measurements indicating the nature and scope of the problem. The assess- ment concentrates on polarization lidar and radiometric observations of persisting contrails from Salt Lake City, Utah, where an extended Project First ISCCP (International Satellite Cloud Climatology Program) Regional Experiment (FIRE) cirrus cloud dataset from the Facility for Atmospheric Remote Sensing has captured new information in a geographical area previously identified as being affected by relatively heavy air traffic. The following contrail properties are consid- ered: hourly and monthly frequency of occurrence; height, temperature, and relative humidity statistics; visible and in- frared radiative impacts; and microphysical content evaluated from in situ data and contrail optical phenomenon such as halos and coronas. Also presented are high-resolution lidar images of contrails from the recent SUCCESS experiment, and the results of an initial attempt to numerically simulate the radiative effects of an observed contrail. The evidence indicates that the direct radiative effects of contrails display the potential for regional climate change at many midlati- tude locations, even though the sign of the climatic impact may be uncertain. However, new information suggests that the unusually small particles typical of many persisting contrails may favor the albedo cooling over the greenhouse warming effect, depending on such factors as the geographic distribution and patterns in day versus night aircraft usage. -

Observation of Polar Stratospheric Clouds Down to the Mediterranean Coast

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 5275–5281, 2007 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/7/5275/2007/ Atmospheric © Author(s) 2007. This work is licensed Chemistry under a Creative Commons License. and Physics Observation of Polar Stratospheric Clouds down to the Mediterranean coast P. Keckhut1, Ch. David1, M. Marchand1, S. Bekki1, J. Jumelet1, A. Hauchecorne1, and M. Hopfner¨ 2 1Service d’Aeronomie,´ Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, B.P. 3, 91371, Verrieres-le-Buisson,` France 2Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe, Institut fur¨ Meteorologie und Klimaforschung, Karlsruhe, Germany Received: 8 March 2007 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 15 May 2007 Revised: 5 October 2007 – Accepted: 6 October 2007 – Published: 12 October 2007 Abstract. A Polar Stratospheric Cloud (PSC) was detected spheric temperatures are expected to cool down due to ozone for the first time in January 2006 over Southern Europe af- depletion, but also to the increase in the concentrations of ter 25 years of systematic lidar observations. This cloud greenhouse gases. Such findings are already reported and was observed while the polar vortex was highly distorted simulated (Ramaswamy et al., 2001), although trends are less during the initial phase of a major stratospheric warming. clear at high latitudes due to a larger natural variability and Very cold stratospheric temperatures (<190 K) centred over potential dynamical feedback. Nearly twenty years after the the Northern-Western Europe were reported, extending down signing of the Montreal Protocol, the timing and extent of the to the South of France -

Ice Polar Stratospheric Clouds Detected from Assimilation of Atmospheric Infrared Sounder Data

Ice Polar Stratospheric Clouds Detected from Assimilation of Atmospheric Infrared Sounder Data Ivanka Stajner,1,2 Craig Benson,3,2 Hui-Chun Liu,1,2 Steven Pawson,2 Nicole Brubaker,1,2 Lang-Ping Chang,1,2 Lars Peter Riishojgaard3,2, and Ricardo Todling1,2 1 Science Applications International Corporation, Beltsville, Maryland 2 Global Modeling and Assimilation Office, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland 3 Goddard Earth Sciences and Technology Center, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Baltimore, Maryland 1 A novel technique is presented for the detection and 45 about ice PSCs (Meerkoetter 1992; Hervig et al. 2001). 2 mapping of ice polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs), 46 Maps of ice PSCs were retrieved from differences in 3 using brightness temperatures from the Atmospheric 47 radiances in two channels and also allowed distinction 4 Infrared Sounder (AIRS) “moisture” channel near 48 between ice PSCs and cirrus. In contrast, even the 5 6.79 μm. It is based on observed-minus-forecast 49 strongest nitric-acid-trihydrate PSCs cannot be 6 residuals (O-Fs) computed when using AIRS 50 retrieved from AVHRR because their signal falls below 7 radiances in the Goddard Earth Observing System 51 AVHRR measurement uncertainty (Hervig et al. 2001). 8 version 5 (GEOS-5) data assimilation system. 52 Tropospheric ice clouds can be retrieved from the 9 Brightness temperatures are computed from six-hour 53 Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) data. 10 GEOS-5 forecasts using a radiation transfer module 54 Comparisons of AIRS spectra with a radiative transfer 11 under clear-sky conditions, meaning they will be too 55 model in the window region 10-12.5 μm show 12 high when ice PSCs are present. -

Contrails, Contrail Cirrus, and Ship Tracks

214 Proceedings of the TAC-Conference, June 26 to 29, 2006, Oxford, UK Contrails, contrail cirrus, and ship tracks K. Gierens* DLR-Institut für Physik der Atmosphäre Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany Keywords: Aerosol effects on clouds and climate ABSTRACT: The following text is an enlarged version of the conference tutorial lecture on con- trails, contrail cirrus, and ship tracks. I start with a general introduction into aerosol effects on clouds. Contrail formation and persistence, aviation’s share to cirrus trends and ship tracks are treated then. 1 INTRODUCTION The overarching theme above the notions “contrails”, “contrail cirrus”, and “ship tracks” is the ef- fects of anthropogenic aerosol on clouds and on climate via the cloud’s influence on the flow of ra- diation energy in the atmosphere. Aerosol effects are categorised in the following way: - Direct effect: Aerosol particles scatter and absorb solar and terrestrial radiation, that is, they in- terfere directly with the radiative energy flow through the atmosphere (e.g. Haywood and Boucher, 2000). - Semidirect effect: Soot particles are very effective absorbers of radiation. When they absorb ra- diation the ambient air is locally heated. When this happens close to or within clouds, the local heating leads to buoyancy forces, hence overturning motions are induced, altering cloud evolu- tion and potentially lifetimes (e.g. Hansen et al., 1997; Ackerman et al., 2000). - Indirect effects: The most important role of aerosol particles in the atmosphere is their role as condensation and ice nuclei, that is, their role in cloud formation. The addition of aerosol parti- cles to the natural aerosol background changes the formation conditions of clouds, which leads to changes in cloud occurrence frequencies, cloud properties (microphysical, structural, and op- tical), and cloud lifetimes (e.g. -

Clarifying the Dominant Sources and Mechanisms of Cirrus Cloud Formation

Clarifying the Dominant Sources and Mechanisms of Cirrus Cloud Formation The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Cziczo, D. J., K. D. Froyd, C. Hoose, E. J. Jensen, M. Diao, M. A. Zondlo, J. B. Smith, C. H. Twohy, and D. M. Murphy. “Clarifying the Dominant Sources and Mechanisms of Cirrus Cloud Formation.” Science 340, no. 6138 (June 14, 2013): 1320–1324. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1234145 Publisher American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Version Author's final manuscript Accessed Wed Mar 16 03:10:42 EDT 2016 Citable Link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/87714 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Clarifying the dominant sources and mechanisms of cirrus cloud formation Authors: Daniel J. Cziczo1*, Karl D. Froyd2,3, Corinna Hoose4, Eric J. Jensen5, Minghui Diao6, Mark A. Zondlo6, Jessica B. Smith7 , Cynthia H. Twohy8, and Daniel M. Murphy2 Affiliations: 1Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA. 2NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory, Chemical Sciences Division, Boulder, CO 80305 USA. 3Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Science, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309 USA. 4Institute for Meteorology and Climate Research – Atmospheric Aerosol Research, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, 76021 Karlsruhe, Germany. 5 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA. 6 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA. 7 School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 02138, USA. -

Both Stratus and Stratocumulus Clouds, Except When Their Tops Are Colder Than About “Congestus” (5C) Are the Largest Cumulus Clouds

358247_358247 6/5/13 6:24 PM Page 1 a guide to the sky 1A. Cirrocumulus. When this high cloud forms, it can give the sky the appearance of 1B. Cirrus (uncinus). A cluster of ice crystals in the form of a hook or tuft forms the top of 1C. Cirrus (spissatus). This is the only cirriform cloud that, by definition is thick enough to 1D. Cirrus (fibratus). These are patchy ice crystal clouds with gently curved or straight wind blowing on a pond of white water. This cloud is often seen on the fringes of storms, and this ice cloud. The larger ice crystals, having fallen below the tuft in strands, are being left produce gray shading except those seen near sunrise and sunset. Sometimes in summer they are filaments. They are older versions of Cirrus clouds. By definition they are not thick enough to after a spell of fine weather, signals a change. Boston, Massachusetts behind. Plymouth, Massachusetts the remnants of Cumulonimbus anvils. Near Sonoma, California produce gray shading except when the sun is low in the sky. Catalina, Arizona 2A. Cirrostratus (nebulosus). This vellum-like ice cloud thickens (more than due to per- 2B. Altostratus. Sunlight fades and brightens as the thicker (opacus) and thinner 2C. Altocumulus (perlucidus). This honeycombed (“perlucidus”) layer cloud usually 2D. Altocumulus (opacus). These thicker layer clouds are the middle-level equivalent of spective) upwind to the west. In winter, rain or snow follows this scene about 70 percent of (translucidus) portions of this icy cloud move rapidly from the southwest. Rain or snow are indicates that large areas (thousands of square km) are undergoing a gradual ascent brought Stratocumulus clouds in structure and depth except that their bases are higher (here about 3-4 the time. -

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms -A- Anvil The flat, spreading top of a cloud, often shaped like an anvil. Thunderstorm anvils may spread hundreds of miles downwind from the thunderstorm itself, and sometimes may spread upwind. Anvil Dome A large overshooting top or penetrating top. -B- Back-building Thunderstorm A thunderstorm in which new development takes place on the upwind side (usually the west or southwest side), such that the storm seems to remain stationary or propagate in a backward direction. Back-sheared Anvil [Slang], a thunderstorm anvil which spreads upwind, against the flow aloft. A back-sheared anvil often implies a very strong updraft and a high severe weather potential. Beaver ('s) Tail [Slang], a particular type of inflow band with a relatively broad, flat appearance suggestive of a beaver's tail. It is attached to a supercell's general updraft and is oriented roughly parallel to the pseudo-warm front, i.e., usually east to west or southeast to northwest. As with any inflow band, cloud elements move toward the updraft, i.e., toward the west or northwest. Its size and shape change as the strength of the inflow changes. Spotters should note the distinction between a beaver tail and a tail cloud. A "true" tail cloud typically is attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same level as the wall cloud itself. A beaver tail, on the other hand, is not attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same height as the updraft base (which by definition is higher than the wall cloud). -

5.6 Attempting to Turn Night Into Day; Development of Visible Like Nighttime Satellite Images

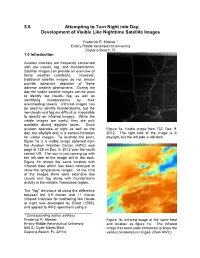

5.6 Attempting to Turn Night into Day; Development of Visible Like Nighttime Satellite Images Frederick R. Mosher * Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Daytona Beach, FL 1.0 Introduction Aviation interests are frequently concerned with low clouds, fog, and thunderstorms. Satellite images can provide an overview of these weather conditions. However, traditional satellite images do not always provide adequate depiction of these adverse weather phenomena. During the day the visible satellite images can be used to identify low clouds, fog, as well as identifying thunderstorms by their overshooting towers. Infrared images can be used to identify thunderstorms, but the low clouds and fog are difficult or impossible to identify on infrared images. While the visible images are useful, they are only available during daylight hours. Since aviation operates at night as well as the Figure 1a. Visible image from 13Z, Dec. 9, day, the daylight only is a serious limitation 2012. The right side of the image is in for visible images. To illustrate the point, daylight, but the left side is still dark. figure 1a is a visible image obtained from the Aviation Weather Center (AWC) web page at 13Z on Dec. 9, 2012 over the south central US. The sun is just coming up with the left side of the image still in the dark. Figure 1b shows the same location with infrared data which has been colorized to show the temperature ranges. At the time of the images there were extensive low clouds and fog along with thunderstorm activity in the eastern Tennessee region. The "fog" technique of using the difference between the 3.9 micron and 11 micron infrared channels for monitoring low clouds at night was developed by Ellrod (1995), and applied to AWC operations using a __________________________________ * Corresponding author address: Frederick R. -

Cirrus Clouds in a Global Climate Model with a Statistical Cirrus Cloud Scheme

Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss., 9, 16607–16682, 2009 Atmospheric www.atmos-chem-phys-discuss.net/9/16607/2009/ Chemistry © Author(s) 2009. This work is distributed under and Physics the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Discussions This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (ACP). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in ACP if available. Cirrus clouds in a global climate model with a statistical cirrus cloud scheme M. Wang1,* and J. E. Penner1 1Department of Atmospheric, Oceanic, and Space Sciences, University of Michigan, USA *now at: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington, USA Received: 18 June 2009 – Accepted: 30 July 2009 – Published: 7 August 2009 Correspondence to: M. Wang ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. 16607 Abstract A statistical cirrus cloud scheme that accounts for mesoscale temperature perturba- tions is implemented into a coupled aerosol and atmospheric circulation model to bet- ter represent both cloud fraction and subgrid-scale supersaturation in global climate 5 models. This new scheme is able to better simulate the observed probability distri- bution of relative humidity than the scheme that was implemented in an older version of the model. Heterogeneous ice nuclei (IN) are shown to affect not only high level cirrus clouds through their effect on ice crystal number concentration but also low level liquid clouds through the moistening effect of settling and evaporating ice crystals. As 10 a result, the change in the net cloud forcing is not very sensitive to the change in ice crystal concentrations associated with heterogeneous IN because changes in high cir- rus clouds and low level liquid clouds tend to cancel. -

Opt Thick PSC 7

CALIPSO observations of wave-induced PSCs with near-unity optical depth over Antarctica in 2006-2007 Noel V.1, Hertzog A.2 and Chepfer H.2 1 Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace, CNRS, Palaiseau, France 2 Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, UPMC Univ. Paris 06, Palaiseau, France Proposed for publication in the Journal of Geophysical Research. Contact: [email protected] Vincent Noel Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique Ecole Polytechnique 91128 Palaiseau, France Tel: 33169335146 Abstract Ground-based and satellite observations have hinted at the existence of Polar Stratospheric Clouds (PSCs) with relatively high optical depths, even if optical depth values are hard to come by. This study documents a Type II PSC observed from spaceborne lidar, with visible optical depths up to 0.8. Comparisons with multiple temperature fields, including reanalyses and results from mesoscale simulations, suggest that intense small-scale temperature fluctuations due to gravity waves play an important role in its formation; while nearby observations show the presence of a potentially related Type Ia PSC further downstream inside the polar vortex. Following this first case, the geographic distribution and microphysical properties of PSCs with optical depths above 0.3 are explored over Antarctica during the 2006 and 2007 austral winters. These clouds are rare (less than 1% of profiles) and concentrated over areas where strong winds hit steep ground slopes in the Western hemisphere, especially over the Peninsula. Such PSCs are colder than the general PSC population, and their detection is correlated with daily temperature minimas across Antarctica. Lidar and depolarization ratios within these clouds suggest they are most likely ice- based (Type II). -

0200 a Characteristic of Pressure Tendency During the Three Hours Preceding the Time of Observation

0200 a Characteristic of pressure tendency during the three hours preceding the time of observation Code figure 0 Increasing, then decreasing; atmospheric pressure the same or higher than three hours ago 1 Increasing, then steady; or increasing, then increasing more slowly Atmospheric pressure now 2 Increasing (steadily or unsteadily)* higher than three hours ago 3 Decreasing or steady, then increasing; or increasing, then increasing more rapidly 4 Steady; atmospheric pressure the same as three hours ago* 5 Decreasing, then increasing; atmospheric pressure the same or lower than three hours ago 6 Decreasing, then steady; or decreasing, then decreasing more slowly Atmospheric pressure now 7 Decreasing (steadily or unsteadily)* lower than three hours ago 8 Steady or increasing, then decreasing; or decreasing, then decreasing more rapidly __________ * For reports from automatic stations, see Regulation 12.2.3.5.3. 0439 bi Ice of land origin Code figure 0 No ice of land origin 1 1–5 icebergs, no growlers or bergy bits 2 6–10 icebergs, no growlers or bergy bits 3 11–20 icebergs, no growlers or bergy bits 4 Up to and including 10 growlers and bergy bits — no icebergs 5 More than 10 growlers and bergy bits — no icebergs 6 1–5 icebergs, with growlers and bergy bits 7 6–10 icebergs, with growlers and bergy bits 8 11–20 icebergs, with growlers and bergy bits 9 More than 20 icebergs, with growlers and bergy bits — a major hazard to navigation / Unable to report, because of darkness, lack of visibility or because only sea ice is visible 0509 CH Clouds