MCEN 5151 – Flow Visualization Matt Phee Clouds 1 Report This Is My

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contrail-Cirrus and Their Potential for Regional Climate Change

Contrail-Cirrus and Their Potential for Regional Climate Change Kenneth Sassen Department of Meteorology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah ABSTRACT After reviewing the indirect evidence for the regional climatic impact of contrail-generated cirrus clouds (contrail- cirrus), the author presents a variety of new measurements indicating the nature and scope of the problem. The assess- ment concentrates on polarization lidar and radiometric observations of persisting contrails from Salt Lake City, Utah, where an extended Project First ISCCP (International Satellite Cloud Climatology Program) Regional Experiment (FIRE) cirrus cloud dataset from the Facility for Atmospheric Remote Sensing has captured new information in a geographical area previously identified as being affected by relatively heavy air traffic. The following contrail properties are consid- ered: hourly and monthly frequency of occurrence; height, temperature, and relative humidity statistics; visible and in- frared radiative impacts; and microphysical content evaluated from in situ data and contrail optical phenomenon such as halos and coronas. Also presented are high-resolution lidar images of contrails from the recent SUCCESS experiment, and the results of an initial attempt to numerically simulate the radiative effects of an observed contrail. The evidence indicates that the direct radiative effects of contrails display the potential for regional climate change at many midlati- tude locations, even though the sign of the climatic impact may be uncertain. However, new information suggests that the unusually small particles typical of many persisting contrails may favor the albedo cooling over the greenhouse warming effect, depending on such factors as the geographic distribution and patterns in day versus night aircraft usage. -

Touching the Clouds Activity Guide

Touching the Clouds Activity Guide Purpose Provide a mental representation of each cloud type Create a tactile cloud identification chart Overview Individuals will construct and touch a tactile model of common types of clouds to learn how to describe the clouds based on their shape and texture. They will compare their descriptions with the standard classifications using the cloud types identified in the GLOBE Clouds Protocol. Time: 45 minutes to 1 ½ hours, depending on individual’s age Level: All Materials (per person) One large sheet of cardstock (18” x 12”) Tape One set of Braille labels for each cloud type and/or markers One small feather A layered piece of blanket or soft fabric (eight 1’ X 1” pieces) Cotton balls of varied sizes One tissue Organza or a similar material, cut into pieces, one layered 1” x 1” piece Pillow stuffing, one 1” x 1” piece A tsp of sand Three paper clips Liquid glue Scissors Baby Wipes Preparation Use tape to divide the large cardstock sheet in four sections: one for the cloud title at the top and three for the altitudes: using a portrait layout, place three pieces of tape horizontally, from side to side of the sheet. 1. 1” off the upper edge of the sheet 2. 8” off the upper edge of the sheet 1 Steps What to do and how to do it: Making A Tactile Cloud Identification Chart 1. Discuss that clouds come in three basic shapes: cirrus, stratus and cumulus. a. Feel of the 4” feather and describe it; discuss that these wispy clouds are high in the sky and are named cirrus. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

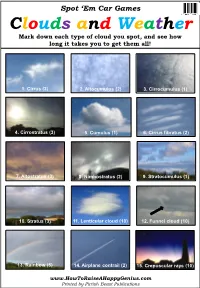

Cloud-Spotting Game Sheet

Spot ‘Em Car Games Clouds and Weather Mark down each type of cloud you spot, and see how long it takes you to get them all! 1. Cirrus (2) 2. Altocumulus (2) 3. Cirrocumulus (1) 4. Cirrostratus (3) 5. Cumulus (1) 6. Cirrus fibratus (2) 7. Altostratus (3) 8. Nimbostratus (2) 9. Stratocumulus (1) 10. Stratus (3) 11. Lenticular cloud (10) 12. Funnel cloud (10) 13. Rainbow (5) 14. Airplane contrail (2) 15. Crepuscular rays (10) www.HowToRaiseAHappyGenius.com Printed by Pictish Beast Publications Spot ‘Em Car Games Clouds and Weather More information about how to identify the weather phenomena that are part of this car game 1. Cirrus: Cirrus clouds look like strands of white cotton wool that have been pulled apart and spread across the sky. 2. Altocumulus: Altocumulus clouds form a layer at mid-altitudes that covers much of the sky, and this layer is usually made up of patterns of regularly spaced and shaped patches with bands of blue sky between them. 3. Cirrocumulus: Cirrocumulus clouds are similar to altocumulus, but they are found higher up in the sky and are made up of smaller patches of cloud. 4. Cirrostratus: Cirrostratus clouds form a continuous sheet of cloud high up in the sky that are thin enough for the sun to be able to shine through, creating a halo effect. 5. Cumulus: Cumulus clouds are distinctive fluffy looking clouds that are clearly separated from other clouds in the sky. They are what you would draw if asked to draw a picture of a cloud. 6. Cirrus fibratus: Cirrus fibratus are a type of Cirrus cloud that form very distinctive long, fluffy lines across the sky. -

Saharan Dust, Convective Lofting, Aerosol Enhancement Zones, And

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres RESEARCH ARTICLE Saharan dust, convective lofting, aerosol enhancement zones, 10.1002/2017JD026933 and potential impacts on ice nucleation in the tropical Key Points: upper troposphere • Relative to background upper tropospheric air, an aerosol C. H. Twohy1 , B. E. Anderson2, R. A. Ferrare2 , K. E. Sauter3 ,T.S.L’Ecuyer3 , enhancement zone (AEZ) exists at the 4 fi 5 2 2 bottom edge of tropical storm anvils S. C. van den Heever , A. J. Heyms eld , S. Ismail , and G. S. Diskin • Storms affected by the SAL have more 1 2 large particles, likely mineral dust, in NorthWest Research Associates, Redmond, Washington, USA, NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, Virginia, USA, the AEZ and these contribute to the 3Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 4Department of background concentration Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA, 5Microscale and Mesoscale Meteorology • Convective lofting of dust by Laboratory, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado, USA convective systems is predicted to enhance ice nucleating particle concentrations in the upper fi fl troposphere Abstract Dry aerosol size distributions and scattering coef cients were measured on 10 ights in 32 clear-air regions adjacent to tropical storm anvils over the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Aerosol properties in these regions were compared with those from background air in the upper troposphere at least 40 km from Supporting Information: • Supporting Information S1 clouds. Median values for aerosol scattering coefficient and particle number concentration >0.3 μm diameter were higher at the anvil edges than in background air, showing that convective clouds loft particles from the Correspondence to: lower troposphere to the upper troposphere. -

Part I Background

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89910-9 - Physics and Chemistry of Clouds Dennis Lamb and Johannes Verlinde Excerpt More information Part I Background © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89910-9 - Physics and Chemistry of Clouds Dennis Lamb and Johannes Verlinde Excerpt More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89910-9 - Physics and Chemistry of Clouds Dennis Lamb and Johannes Verlinde Excerpt More information 1 Introduction 1.1 Importance of clouds What would our world be like without clouds? Unimaginable – quite literally – for clouds are essential for our lives on earth. Humans, and for that matter most other land-dwelling species, would simply not exist, let alone thrive in the absence of the fresh water that clouds supply. The favorable climate we have enjoyed for thousands of years might also not exist in the absence of atmospheric water and clouds. A world without clouds would be different indeed. Clouds contribute to the environment in many ways. Clouds, through a variety of phys- ical processes acting over many spatial scales, provide both liquid and solid forms of precipitation and nature’s only significant source of fresh water. Under extreme circum- stances, however, clouds and precipitation may not form at all, leading to prolonged droughts in some regions. At other times and places, too much rain or snow falls, giv- ing rise to devastating floods or blizzards. Liquid rain drops bring usable water directly to the surface, while simultaneously carrying many trace chemicals out of the atmosphere and into the ecosystems of the Earth. -

Both Stratus and Stratocumulus Clouds, Except When Their Tops Are Colder Than About “Congestus” (5C) Are the Largest Cumulus Clouds

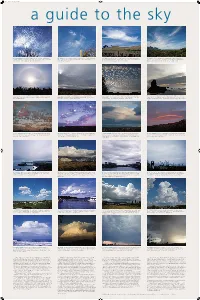

358247_358247 6/5/13 6:24 PM Page 1 a guide to the sky 1A. Cirrocumulus. When this high cloud forms, it can give the sky the appearance of 1B. Cirrus (uncinus). A cluster of ice crystals in the form of a hook or tuft forms the top of 1C. Cirrus (spissatus). This is the only cirriform cloud that, by definition is thick enough to 1D. Cirrus (fibratus). These are patchy ice crystal clouds with gently curved or straight wind blowing on a pond of white water. This cloud is often seen on the fringes of storms, and this ice cloud. The larger ice crystals, having fallen below the tuft in strands, are being left produce gray shading except those seen near sunrise and sunset. Sometimes in summer they are filaments. They are older versions of Cirrus clouds. By definition they are not thick enough to after a spell of fine weather, signals a change. Boston, Massachusetts behind. Plymouth, Massachusetts the remnants of Cumulonimbus anvils. Near Sonoma, California produce gray shading except when the sun is low in the sky. Catalina, Arizona 2A. Cirrostratus (nebulosus). This vellum-like ice cloud thickens (more than due to per- 2B. Altostratus. Sunlight fades and brightens as the thicker (opacus) and thinner 2C. Altocumulus (perlucidus). This honeycombed (“perlucidus”) layer cloud usually 2D. Altocumulus (opacus). These thicker layer clouds are the middle-level equivalent of spective) upwind to the west. In winter, rain or snow follows this scene about 70 percent of (translucidus) portions of this icy cloud move rapidly from the southwest. Rain or snow are indicates that large areas (thousands of square km) are undergoing a gradual ascent brought Stratocumulus clouds in structure and depth except that their bases are higher (here about 3-4 the time. -

Cloud Forming Properties of Ambient Aerosol in the Netherlands and Resultant Shortwave Radiative Forcing of Climate"

Andrey Khlystov » CLOUD FORMING PROPERTIES OFAMBIEN T AEROSOL IN THE NETHERLANDS ANDRESULTAN T SHORTWAVE RADIATIVE FORCING OF CLIMATE PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van de Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen prof. dr. C.M. Karssen, in het openbaar te verdedigen opmaanda g 16maar t 1998 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula Promotor: Dr. J. Slanina hoogleraar in de meetmethoden in atmospherisch onderzoek Co-promotor: Dr. H.M. ten Brink Energieonderzoek Centrum Nederland (ECN) ob 0uce>2dt^ Stellingen behorende bij het proefschrift "CLOUD FORMING PROPERTIES OF AMBIENT AEROSOL IN THE NETHERLANDS AND RESULTANT SHORTWAVE RADIATIVE FORCING OF CLIMATE" A.Khlystov 1. The effective radius of cloud droplets deduced from satellite measurements should not be used to estimate the indirect aerosol forcing unless the liquid water content is simultaneously assessed. 2. A substantial effort has been made to characterize broken clouds. However it is over-optimistic to compare in-cloud measurements and satellite observations ofreflectiv e properties ofsuc h clouds. 3. The continuing use ofinstrumentatio n that has not been calibrated is a major impediment for aerosol research to be considered as a serious branch of science. 4. Contrary to common belief, considerable efforts are required to achieve a reasonable accuracy (of at least 20%) in measurement of aerosol number concentrations. 5. Due to the relatively low size resolution of cascade impactors it is always possible to fit the data to a multimodal distribution. 6. One should not use the observed changes in (global) temperature as proof that present climate models accurately predict the effects ofanthropogeni c pollution on the global climate. -

Enhanced Shortwave Cloud Radiative Forcing Due to Anthropogenic Aerosols

BNL -61815 ENHANCED SHORTWAVE CLOUD RADIATIVE FORCING DUE TO ANTHROPOGENIC AEROSOLS S. E. Schwartz Environmental Chemistry Division Department of Applied Science Brookhaven National Laboratory Upton, NY 11973 and A. Slingo Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research Meteorological Office, London Road, Bracknell Berkshire RG 12 2SY United Kingdom May 1995 Submitted for publication in Clouds. Chemistry and Climate-- Jbceredings of NATO Advanced Research Worksha, Crutzen, P. and Ramanathan, V., Eds. Springer, Heidelberg, 1995 acceptance of this' article, the publisher and/or recipient acknowledges the U.S. Government'sBy right to retain a non exclusive, royalty-free license in and to any copyright covering this paper. This research was peiformed under the auspices of the U.S. Depwent of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-76CH00016. DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electrcmic image products. Images are producedl from the best available original documenit. t I ENHANCED SHORTWAVE CLOUD RADIATIVE FORCING DUE TO ANTHROPOGENIC AEROSOLS S. E. Schwartz Environmental Chemj stry Division Brookhaven National Laboratory Upton NY 11973 USA and A. Slingo Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research Meteorological Office, London Road, Bracknell Berkshire RG12 2SY CK It has been suggested,, originally by Twomey (SCEP, 1970), that anthropogenic aerosols in the troposphere can influence the microphysical properties of clouds and in turn their reflectivity (albedo), thereby exerting a radiative influence on climate. This chapter presents the theoretical basis for of this so-called indirect forcing and reviews pertinent observational evidence and climate model calculations of its magnitude and geographical distribution. We restrict consideration to liquid-water clouds, in part because these clouds are the principal clouds thought to be influenced by anthropogenic aerosols, and in part because the processes responsible for nucleation of ice clouds are not sufficiently well understood to permit much to be said about any anthropogenic influence. -

New Edition of the International Cloud Atlas by Stephen A

BULLETINVol. 66 (1) - 2017 WEATHER CLIMATE WATER CLIMATE WEATHER New Edition of the International Cloud Atlas An Integrated Global The Evolution of Greenhouse Gas Information Climate Science: A System, page 38 Personal View from Julia Slingo, page 16 WMO BULLETIN The journal of the World Meteorological Organization Contents Volume 66 (1) - 2017 A New Edition of the International Secretary-General P. Taalas Cloud Atlas Deputy Secretary-General E. Manaenkova Assistant Secretary-General W. Zhang by Stephen A. Cohn . 2 The WMO Bulletin is published twice per year in English, French, Russian and Spanish editions. Understanding Clouds to Anticipate Editor E. Manaenkova Future Climate Associate Editor S. Castonguay Editorial board by Sandrine Bony, Bjorn Stevens and David Carlson E. Manaenkova (Chair) S. Castonguay (Secretary) . 8 R. Masters (policy, external relations) M. Power (development, regional activities) J. Cullmann (water) D. Terblanche (weather research) Y. Adebayo (education and training) Seeding Change in Weather F. Belda Esplugues (observing and information systems) Modification Globally Subscription rates Surface mail Air mail 1 year CHF 30 CHF 43 by Lisa M.P. Munoz . 12 2 years CHF 55 CHF 75 E-mail: [email protected] The Evolution of Climate Science © World Meteorological Organization, 2017 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form by Dame Julia Slingo . 16 and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Edito- rial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or WMO Technical Regulations translate this publication (articles) in part or in whole should be addressed to: An interview with Dimitar Ivanov Chairperson, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) by WMO Secretariat . -

A N0AA AVHRR Cloud Climatology Over Scandinavia Covering the Period 1991-2000

SMHI No 97, Jun 2001 Reports Meteorology and Climatology Kebnekaise -- Norwegian Sea Malung Klaipeda (%) 100 80 60 40 Viixjö 20 0 A N0AA AVHRR cloud climatology over Scandinavia covering the period 1991-2000 Karl-Göran Karlsson Cover: A1ea11 clo11d ji-eq11mcies i11 the rl}temoo11 i11 }116, (i11 rolo/11) f/11d the a11,11wl coursc ofdoud couerfor so,ne se!ectcd positions in the Scandi,Jtwir111 arcfl (rnrve plots) deriued ji-om fl te11-ymr NOM AVHRR rlfltf/ set 1991-2000. RMK No 97, Jun 2001 A NOAA AVHRR cloud climatology over Scandinavia covering the period 1991-2000 Karl-Göran Karlsson R eoort s ummary /Rapportsammanfattn1n2 lssuing .-\gerKy Utgi\·;m.: Report numher/Publikation Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological lnstitute RMK No. 97 S-601 76 NORRKÖPING Repor! date/Utgivningsdatum Sweden June 2001 Author (s) Förfallarc Karl-Göran Karlsson Title (rn1d Subtitle Titd A NOAA AVHRR cloud climatology over Scandinavia covering thc period 1991-2000 Abstract Sammandrag A tcn-year NOAA A VHRR cloud climatology with a horizontal resolution of four km has been compiled over the Scandinavian region based on results from near real-lime cloud classifications of the SMHl SCANDlA mode!. The frequency and geographic distribution ofthe cloud groups Low-, Medium- and High-level clouds, water and ice clouds and deep convective clouds have been studied in addition to the ten-ycar monthly means of total fractional cloud cover in the region. Furthennore, attempts to estimatc the diurnal cycle of cloudiness and typieal cloud patterns in various weather rcgimes (e.g., North Atlantie Oscillation phases) have been made. The cloud climate in the region was found ta be significantly affected by the distribution of land and sea. -

0200 a Characteristic of Pressure Tendency During the Three Hours Preceding the Time of Observation

0200 a Characteristic of pressure tendency during the three hours preceding the time of observation Code figure 0 Increasing, then decreasing; atmospheric pressure the same or higher than three hours ago 1 Increasing, then steady; or increasing, then increasing more slowly Atmospheric pressure now 2 Increasing (steadily or unsteadily)* higher than three hours ago 3 Decreasing or steady, then increasing; or increasing, then increasing more rapidly 4 Steady; atmospheric pressure the same as three hours ago* 5 Decreasing, then increasing; atmospheric pressure the same or lower than three hours ago 6 Decreasing, then steady; or decreasing, then decreasing more slowly Atmospheric pressure now 7 Decreasing (steadily or unsteadily)* lower than three hours ago 8 Steady or increasing, then decreasing; or decreasing, then decreasing more rapidly __________ * For reports from automatic stations, see Regulation 12.2.3.5.3. 0439 bi Ice of land origin Code figure 0 No ice of land origin 1 1–5 icebergs, no growlers or bergy bits 2 6–10 icebergs, no growlers or bergy bits 3 11–20 icebergs, no growlers or bergy bits 4 Up to and including 10 growlers and bergy bits — no icebergs 5 More than 10 growlers and bergy bits — no icebergs 6 1–5 icebergs, with growlers and bergy bits 7 6–10 icebergs, with growlers and bergy bits 8 11–20 icebergs, with growlers and bergy bits 9 More than 20 icebergs, with growlers and bergy bits — a major hazard to navigation / Unable to report, because of darkness, lack of visibility or because only sea ice is visible 0509 CH Clouds