Electoral Politics in Bihar and Orissa: a Comparative Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXI NO. 5 DECEMBER - 2014 MADHUSUDAN PADHI, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary RANJIT KUMAR MOHANTY, O.A.S, ( SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Shrikshetra, Matha and its Impact Subhashree Mishra ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 India International Trade Fair - 2014 : An Overview Smita Kar ... 7 Mo Kahani' - The Memoir of Kunja Behari Dash : A Portrait Gallery of Pre-modern Rural Odisha Dr. Shruti Das ... 10 Protection of Fragile Ozone Layer of Earth Dr. Manas Ranjan Senapati ... 17 Child Labour : A Social Evil Dr. Bijoylaxmi Das ... 19 Reflections on Mahatma Gandhi's Life and Vision Dr. Brahmananda Satapathy ... 24 Christmas in Eternal Solitude Sonril Mohanty ... 27 Dr. B.R. Ambedkar : The Messiah of Downtrodden Rabindra Kumar Behuria ... 28 Untouchable - An Antediluvian Aspersion on Indian Social Stratification Dr. Narayan Panda ... 31 Kalinga, Kalinga and Kalinga Bijoyini Mohanty .. -

WP7 Biswamoy Pati

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Research Online Asia Research Centre Working Paper 7 IDENTITY, HEGEMONY, RESISTANCE: CONVERSIONS IN ORISSA, 1800-2000 Dr Biswamoy Pati 1 Identity, Hegemony, Resistance: Conversions in Orissa œ 1800-2000 IDENTITY, HEGEMONY, RESISTANCE: CONVERSIONS IN ORISSA, 1800-2000* The Problem: It is widely held that as far as Hinduism is considered, the concept of conversion does not exist. Traditionally, it is said that one cannot become a Hindu by conversion, since one has to be born a Hindu and indeed, innumerable tracts, articles and books have been written on the subject. 1 However, as this paper will attempt to show, the ground realities of social dynamics would appear to suggest something different and this premise (that one cannot become a Hindu) may, in a profound sense, be open to contest. One can cite here the history of the adivasi peoples and their absorption into brahminical Hinduism - a social process that would, in fact, point to the gaps and contradictions existing between this kind of traditional belief (in the impossibility of ”conversion‘ to Hinduism) and the complexities of actual cultural practice on the ground. In other words, this paper seeks to argue that the history of the indigenous peoples would instead seem to suggest that, in an important sense, Hinduism did ”convert‘, and the paper further goes on to raise the question whether adivasis and outcastes were/are Hindus in the first place. 2 ”Common-sense‘ dictates that this absence of a system of conversion within Hinduism makes it by implication, more humane, tolerant and perhaps superior to proselytising religions like Islam and Christianity. -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution In

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Review Article Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution in Indian Populations and its Significance in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) - A Review Based Molecular Approach Sinha M1*, Rao IA1 and Mitra M2 1Department of Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas Abstract University, India Disaster Victim Identification is an important aspect in mass disaster cases. 2School of Studies in Anthropology, Pt. Ravishankar In India, the scenario of disaster victim identification is very challenging unlike Shukla University, India any other developing countries due to lack of any organized government firm who *Corresponding author: Sinha M, Department of can make these challenging aspects an easier way to deal with. The objective Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas University, India of this article is to bring spotlight on the potential and utility of uniparental DNA haplogroup databases in Disaster Victim Identification. Therefore, in this article Received: December 08, 2016; Accepted: January 19, we reviewed and presented the molecular studies on mitochondrial and Y- 2017; Published: January 24, 2017 chromosomal DNA haplogroup distribution in various ethnic populations from all over India that can be useful in framing a uniparental DNA haplogroup database on Indian population for Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). Keywords: Disaster Victim identification; Uniparental DNA; Haplogroup database; India Introduction with the necessity mentioned above which can reveal the fact that the human genome variation is not uniform. This inconsequential Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is the recognized practice assertion put forward characteristics of a number of markers ranging whereby numerous individuals who have died as a result of a particular from its distribution in the genome, their power of discrimination event have their identity established through the use of scientifically and population restriction, to the sturdiness nature of markers to established procedures and methods [1]. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Prayer-Guide-South-Asia.Pdf

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

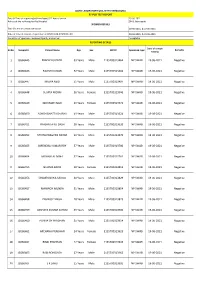

RT-PCR-19-06-2021- Negative (1).Xlsx

COVID LABORATORY OLD, DHH JHARSUGUDA RT-PCR TEST REPORT Date & Time of reporting(dd/mm/yyyy)//12 hours format 19-06-2021 Adress of the reffering facility/Hospital DHH, Jharsuguda SPCIMEN DETAILS Date & time of sample collection 18-06-2021, & 19-06-2021 Date of time of receipt of specimen at COVID LAB JHARSUGUDA 18-06-2021, & 19-06-2021 Condition of specimen received/Quality and arrival Acceptable REPORTING DETAILS Date of sample SL No. Sample ID Patient Name Age Sex SRF ID Specimen type Remarks testing 1 JSG66445 PRADIP KU PATEL 53 Years Male 2135700313464 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 2 JSG66446 RAJESH KUMAR 52 Years Male 2135700313482 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 3 JSG66447 NRUPA NEGI 51 Years Male 2135700313497 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 4 JSG66448 SUJATA MORAI 26 Years Female 2135700313546 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 5 JSG66449 INDUMATI NAIK 29 Years Female 2135700313572 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 6 JSG66450 ASHISH BHATTACHARYA 49 Years Male 2135700313624 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 7 JSG66451 PRASANTA KU DASH 50 Years Male 2135700313635 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 8 JSG66452 STHITA PRAGYAN NAYAK 30 Years Male 2135700313676 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 9 JSG66453 BIRENDRA KUMAR ROY 57 Years Male 2135700313700 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 10 JSG66454 MOHANLAL MINA 37 Years Male 2135700313761 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 11 JSG66455 NILOMA BARIK 28 Years Female 2135700313812 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 12 JSG66456 DINAKRUSHNA SAHOO 40 Years Male 2135700313829 NP SWAB 19-06-2021 Negative 13 JSG66457 MANINGH MUNDA 51 Years Male 2135700313854 -

Book Modernity and Folklore.Indb

Ramcharitmanas to Dhnoraicharitmanas: An Overview of the Construction of Identity of an Indian and India Ronita Bhattacharya University of Georgia 95 “Probably no work of world literature, secular in origin, has ever produced so profound an infl uence on the life and thought of a people as the Ramayana” A. A. Macdonnell In Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson made famous the argument that the nation lives in homogeneous empty time. In this argument, he follows a dominant strand in modern historical thinking that imagines the social space of modernity as distributed in homogeneous empty space what a Marxist would call the time of Capital. Anderson explicitly adopts the formulation from Walter Benjamin and uses it to show the material possibilities of large anonymous societies formulated by the simultaneous experiences of reading the daily newspaper and following the private lives of popular fi ctional characters (Chatterjee, Th e Politics of the Governed 4). But, what happens in the case of a community that is defi ned by an epic and that extends from a pre-capitalist to a capitalist time? Imagine a situation where stories are shared independently of the literacy of the people and of what we understand as the media. How is this situation conducive to the construction of an imagined community? Th ere is one such community that spans at least three-fourths of Asia, encompassing hundreds of linguistic and ethnic groups that share neither national boundaries nor a religious identity nor even the “same” story, since there was and still is not any sanction to restrict the story into one “original” version. -

RGICS LEGISLATIVE BRIEF (January, 2017)

RGICS RAJIV GANDHI INSTITUTE FOR CONTEMPORARY STUDIES JAWAHAR BHAWAN, DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD ROAD, NEW DELHI-110001 RGICS LEGISLATIVE BRIEF (January, 2017) The Constitution Amendment (Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe) Order (Amendment) Bill, 2016 Jeet Singh Social Cluster RGICS legislative brief The Constitution Amendment (Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe) Order (Amendment) Bill, 2016 2 PART: I Key Messages The Constitutional Amendment (Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe) Order (Amendment) Bill, 2016 proposes to include 23 different communities of Assam, Tripura, Tamil Nadu, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand in the list STs. Despite political consensus and approval of the National Commission for Scheduled Tribe and the previous government, the NDA government took more than two and half years to move this constitutional amendment Bill. Currently there are 210 proposals of different communities for inclusion in the list of STs pending with Central government for final approval. The Bill attempts to resolve only 12 out of 210 proposals seeking ST categorization. PART: II Introduction The introduction of ‘The Constitution Amendment (Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe) Order (Amendment) Bill, 2016’ in Lok Sabha in December 2016 by NDA government has brought good news for nearly 23 tribal communities. The Union Minister of Trabal Affairs Mr. Jual Oram while introduction of the Bill in the Lok Sabha said that the Bill has accepted some proposals of inclusion of few communities in the list of ST requested by five states governments- Assam, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Tamil Nadu and Tripura. The Bill reads, “the Bill seeks to include certain communities as well as addition of synonyms of communities in the existing lists of Scheduled Tribes.” For many of these communities, the demand of ST categorization is very old and they fought a long battle for their rightful due. -

Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CASTE, KINSHIP AND SEX RATIOS IN INDIA Tanika Chakraborty Sukkoo Kim Working Paper 13828 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13828 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2008 We thank Bob Pollak, Karen Norberg, David Rudner and seminar participants at the Work, Family and Public Policy workshop at Washington University for helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Lauren Matsunaga and Michael Scarpati for research assistance and Cassie Adcock and the staff of the South Asia Library at the University of Chicago for their generous assistance in data collection. We are also grateful to the Weidenbaum Center and Washington University (Faculty Research Grant) for research support. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim NBER Working Paper No. 13828 March 2008 JEL No. J12,N35,O17 ABSTRACT This paper explores the relationship between kinship institutions and sex ratios in India at the turn of the twentieth century. Since kinship rules varied by caste, language, religion and region, we construct sex-ratios by these categories at the district-level using data from the 1901 Census of India for Punjab (North), Bengal (East) and Madras (South). -

1) SNC Lavalin Scandal

1) SNC Lavalin scandal The SNC Lavalin scandal is financial scam related to the contracting of the government with a Canadian company, SNC-Lavalin which resulted in an alleged net loss to the exchequer of 374.50 crore in the renovation and modernization works of the hydro electric power stations at Pallivasal (37.5 mw), Sengulam (48 mw) and Panniar (30 mw) - also known as PSP project in short - installed in between 1940 and 1964 at Idukki district in Kerala state of India. Several politicians were involved and eventually charged, including former ministers G. Karthikeyan of Indian National Congress, Vijayan. The first Politburo member in the CPI (M) history to be prosecuted in a corruption case. History In 1992, the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) of India rejected a proposal of Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) to renovate the three hydro-electric power projects at Pallivasal, Sengulam and Panniar instead the CEA recommended a capacity upgradation of the generators in these three power projects, after they found that these projects are in good condition. KSEB disregarded this recommendation and went forward with the decision to renovate these projects. The initial negotiations with the Canadian company SNC-Lavalin - a company which had been present in the state's power sector for several decades - began during the tenure of United Democratic Front government, [7] under the leadership of the then power minister C.V. Padmarajan and later, the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with SNC-Lavalin on 10 August 1995, when G. Karthikeyan of the Congress Party was the power minister, after the resignation of C.V. -

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study Change Is

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study Change is a difference through time in the object to which it is applied. Whenever the change is appeared, it starts to show the physical, political, economical, cultural, social, moral, psychological and natural differences than the previous. Social change is a process. A process means continuous change taking place in a definite manner through the operation of forces present from the first within the situation. Change as a process is the definite step by manner through which one stage or stages merges into another. It is very nature of culture to undergo change. In one aspect, culture is valuation. In another it is expression. Valuations change with changing experiences, whether the experience brings satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Every age has its own appraisement of the thing worthwhile, relevant in its literal.( Maciver & Page, 2009) Nepal has provided shelter and security for a large number of migrants from different places comprising races and represent different ethnic, cultural and linguistic background. The Aagneya, Dravid, Brachy-cephalic,Aryan and Mangol(Sharma:2039) races are the dweller of this subcontinent . The major groups, according to racial origins are Indo- Aryan, Tibeto-Burman and Astro-Asiatic (KC1995). Kewats occupy the rank of indigenous and touchable in the Hindu mythological founded society. Although they are minority in number, they can be found in most of the part of Nepal i.e. hill and terai. Majority are dwelling in central development region. They are shudra and their traditional occupations are fishing and boating. Kewats are a community of boatman who live along the banks of Ganga River.