Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A ,JUSTIFICATION of RESERVATION Forobcs (A CRI1''ique of SHO:URIE & ORS.)

GEN. EDITOR: DR. A. R. DESAI A ,JUSTIFICATION OF RESERVATION FOROBCs (A CRI1''IQUE OF SHO:URIE & ORS.) MIHIRDESAI C.G. SHAll !\IE!\lORIAL TRUST PUBLICATION (20) C. G. Shah Memorial Trust Publication (20) A JUSTIFICATION OF RESERVATIONS FOR OBCs by MIHIR DESAI Gen. EDITOR DR. A. R. DESAI. IN COLLABORATION WITH HUMAN RIGHTS & LAW NETWORK BOMBAY. DECEMBER 1990 C. G. Shah Memorial Trust, Bombay. · Distributors : ANTAR RASHTRIY A PRAKASHAN *Nambalkar Chambers, *Palme Place, Dr. A. R. DESAI, 2nd Floor, Calcutta-700 019 * Jaykutir, Jambhu Peth, (West Bengal) Taikalwadi Road, Dandia Bazar, · Mahim P.O., Baroda - 700 019 Bombay - 400 016 Gujarat State. * Mihir Desai Engineer House, 86, Appollo Street, Fort, Bom'Jay - 400 023. Price: Rs. 9 First Edition : 1990. Published by Dr. A. K. Desai for C. G. Shah Memorial Trust, Jaykutir, T.:;.ikaiwadi Road, Bombay - 400 072 Printed by : Sai Shakti(Offset Press) Opp. Gammon H::>ust·. Veer Savarkar Marg, Prabhadevi, Bombay - 400 025. L. A JUSTIFICATION OF RESERVATIONS FOROOCs i' TABLE OF CONTENTS -.-. -.-....... -.-.-........ -.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-. S.No. Particulars Page Nos. -.- ..... -.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-. 1. Forward (i) - (v) 2. Preface (vi) - 3. Introduction 1 - 3 4. The N.J;. Government and 3 - 5' Mandai Report .5. Mandai Report 6 - 14 6. The need for Reservation 14 - 19 7. Is Reservation the Answer 19 - 27 8. The 10 Year time-limit .. 28 - 29 9. Backwardness of OBCs 29 - 39 10. Socia,l Backwardness and 39 - 40' Reservations 11. ·Criteria .for Backwardness 40 - 46 12. lnsti tutionalisa tion 47 - 50 of Caste 13. Economic Criteria 50 - 56 14. The Merit Myth .56 - 64 1.5. -

Status of Entitlement Issued by Accountant General in July, 2020 in Respect of Gazetted Officers

ENTITLEMENTS AUTHORISED/ISSUED BY ACCOUNTANT GENERAL IN July 2020 IN RESPECT OF GAZETTED OFFICER PAY SLIP ISSUED NAME DESIGNATION STATUS Ajay Kumar अधधकण अभभययतत (ससवतभनववत) ISSUED Ajay Kumar Srivastava No-1 PRINCIPAL JUDGE, FAMILY COURT ISSUED Akhilesh Kumar District co-operative officer ISSUED Alok Kumar TECHNICAL ADVISOR ISSUED Amar Singh कतयरपतलक अभभययतत, ISSUED Amarendra Prasad Singh (भनलयभबत ) ISSUED Amrit Lal Meena अपर ममखय सभचव, ISSUED Anil Kumar Superintending Engineer, ISSUED Anil Kumar Anand Senior Reporter, ISSUED Anil Kumar Thakur Retired Medical Officer, ISSUED Anwar Hussain Member, Bihar Police Sub-ordinate Services Commission, Santosh Mansion, ISSUED B-Block, Near R.P.S. Law College, Arbind Prasad Shahi Retd District Immunisation Officer, Katihar ISSUED Arun Kumar Medical Officer, ISSUED Arun Kumar Sinha Executive Engineer, ISSUED Arun Kumar Srivastava PRINCIPAL JUDGE, FAMILY COURT ISSUED Arunish Chawla Central deputation ISSUED Arvind Kumar Pandey Principal Chief Conservator of Forests(HOFF) ISSUED Ashesh Kumar Retd. Superintendent ISSUED Ashok Kumar Chaudhary Superintending Engineer, ISSUED Ashok Kumar Jha Executive Engineer(NABARD,External Sustained), Chief Engineer(Budget & ISSUED Planning) Ashok Kumar Yadav Dy. Director, Medical Education Deptt. ISSUED Atma Nand Kumar Civil Surgeon Cum Chief Medical Officer ISSUED Awdhesh Kumar Civil Surgeon Cum Chief Medical Officer ISSUED Ayodhya Singh Additional S.P. (Operation), ISSUED Bharat Singh Professor ISSUED Bhaskar Chandra Bharti DIVISIONAL FOREST OFFICER, PURNEA ISSUED -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Aump Mun 3.0 All India Political Parties' Meet

AUMP MUN 3.0 ALL INDIA POLITICAL PARTIES’ MEET BACKGROUND GUIDE AGENDA : Comprehensively analysing the reservation system in the light of 21st century Letter from the Executive Board Greetings Members! It gives us immense pleasure to welcome you to this simulation of All India Political Parties’ Meet at Amity University Madhya Pradesh Model United Nations 3.0. We look forward to an enriching and rewarding experience. The agenda for the session being ‘Comprehensively analysing the reservation system in the light of 21st century’. This study guide is by no means the end of research, we would very much appreciate if the leaders are able to find new realms in the agenda and bring it forth in the committee. Such research combined with good argumentation and a solid representation of facts is what makes an excellent performance. In the session, the executive board will encourage you to speak as much as possible, as fluency, diction or oratory skills have very little importance as opposed to the content you deliver. So just research and speak and you are bound to make a lot of sense. We are certain that we will be learning from you immensely and we also hope that you all will have an equally enriching experience. In case of any queries feel free to contact us. We will try our best to answer the questions to the best of our abilities. We look forward to an exciting and interesting committee, which should certainly be helped by the all-pervasive nature of the issue. Hopefully we, as members of the Executive Board, do also have a chance to gain from being a part of this committee. -

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India Vani K. Borooah, Amaresh Dubey and Sriya Iyer ABSTRACT This article investigates the effect of jobs reservation on improving the eco- nomic opportunities of persons belonging to India’s Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST). Using employment data from the 55th NSS round, the authors estimate the probabilities of different social groups in India being in one of three categories of economic status: own account workers; regu- lar salaried or wage workers; casual wage labourers. These probabilities are then used to decompose the difference between a group X and forward caste Hindus in the proportions of their members in regular salaried or wage em- ployment. This decomposition allows us to distinguish between two forms of difference between group X and forward caste Hindus: ‘attribute’ differences and ‘coefficient’ differences. The authors measure the effects of positive dis- crimination in raising the proportions of ST/SC persons in regular salaried employment, and the discriminatory bias against Muslims who do not benefit from such policies. They conclude that the boost provided by jobs reservation policies was around 5 percentage points. They also conclude that an alterna- tive and more effective way of raising the proportion of men from the SC/ST groups in regular salaried or wage employment would be to improve their employment-related attributes. INTRODUCTION In response to the burden of social stigma and economic backwardness borne by persons belonging to some of India’s castes, the Constitution of India allows for special provisions for members of these castes. -

Contributions of Lala Har Dayal As an Intellectual and Revolutionary

CONTRIBUTIONS OF LALA HAR DAYAL AS AN INTELLECTUAL AND REVOLUTIONARY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^ntiat ai pijtl000pi{g IN }^ ^ HISTORY By MATT GAOR CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2007 ,,» '*^d<*'/. ' ABSTRACT India owes to Lala Har Dayal a great debt of gratitude. What he did intotality to his mother country is yet to be acknowledged properly. The paradox ridden Har Dayal - a moody idealist, intellectual, who felt an almost mystical empathy with the masses in India and America. He kept the National Independence flame burning not only in India but outside too. In 1905 he went to England for Academic pursuits. But after few years he had leave England for his revolutionary activities. He stayed in America and other European countries for 25 years and finally returned to England where he wrote three books. Har Dayal's stature was so great that its very difficult to put him under one mould. He was visionary who all through his life devoted to Boddhi sattava doctrine, rational interpretation of religions and sharing his erudite knowledge for the development of self culture. The proposed thesis seeks to examine the purpose of his returning to intellectual pursuits in England. Simultaneously the thesis also analyses the contemporary relevance of his works which had a common thread of humanism, rationalism and scientific temper. Relevance for his ideas is still alive as it was 50 years ago. He was true a patriotic who dreamed independence for his country. He was pioneer for developing science in laymen and scientific temper among youths. -

KARPOORI THAKUR (24 January 1924-17 February 1988)

KARPOORI THAKUR (24 January 1924-17 February 1988) Veteran Socialist leader Karpoori Thakur, son of Gokul Thakur & Ramdulari Devi, was born at Ismail Nagar alias Pitaunjhia (now renamed to Karpuri Gram) village of the Samastipur District of British India on 24th January 1924. He was educated at Upper Primary School, Pitaujhjia Middle English School, Tajpur, Tirhut Academy, Samastipur and Chandradhari Mithila College, Darbhanga. He Studied up to III year B.A. As a student activist, he left his graduate college to join the Quit India Movement of 1942. For his participation in the Indian independence movement, he spent 26 months in prison during National movement. He was Librarian, Youth Library in Home Village, 1935-40.Member, Students' Federation, 1937- 42.Assistant Secretary, Bihar Pradeshik Kisan Sabha, 1947. Secretary, (i) Bihar Pradeshik Kisan Sabha, 1948-52, (ii) Bihar Relief Committee; Member, Central Committee of Akhil Bhartiya Hind Kisan Panchayat; Member, Bihar State Level Bhoodan or Sarvodaya Committee. After India gained independence, Karpoori Thakur worked as a teacher in his village school. He became a member of the Bihar Vidhan Sabha during first general elections in 1952 as Socialist Party candidate and almost remained member of Vidhan Sabha till his death. He was Political and Social Worker, previously associated with the Congress Socialist Party, Socialist Party, Praja Socialist Party, Samyukta Socialist Party, Samyukta Socialist Party (Lohia), Bharatiya Lok Dal, Janata Party, Janata Party (S), Lok Dal (K), Janata Party, Dalit Mazdoor Kisan Party and Lok Dal. Karpoori Thakur was Secretary, Darbhanga District Congress Socialist Party, 1945-47. Joint Secretary/Secretary, Bihar Socialist Party, 1948-52.During 1952-72, he held the offices of (i) Provincial Secretary, Praja Socialist Party, Bihar, (ii) Member, National Working Committee of All-India Praja Socialist Party, (iii) Chairman, Samyukta Socialist Party, Bihar. -

List of Roll Numbers for 'Ayurvedic Pharmacist-470' Examination Date 4.9.2016 (10 AM to 12 Noon)

List of Roll Numbers for 'Ayurvedic Pharmacist-470' Examination date 4.9.2016 (10 AM to 12 Noon) Applicatio Name of Father/Husba DOB Roll No Examination Centre n ID Candidate nd Name 81004 NEENA DEVI SHAMSHER 18/02/1984 470000001 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre SINGH One, District Hamirpur (HP) 69728 Dinesh S/O: Babu 12/4/1990 470000002 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kumar Ram One, District Hamirpur (HP) 24497 Sameena W/O Sher 17/03/1986 470000003 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Devi Khan One, District Hamirpur (HP) 31483 Kamal S/O Jagdish 29/11/1984 470000004 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kumar Singh One, District Hamirpur (HP) 35534 Indu Bala D/O Vikram 7/2/1986 470000005 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kashyap Singh One, District Hamirpur (HP) 61994 Sunil Kumar S/O Tulsi Ram 15/11/1982 470000006 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre One, District Hamirpur (HP) 31257 Vinod Kumar S/O Amar 23/09/1984 470000007 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Singh One, District Hamirpur (HP) 30989 Anil Kumar S/O Pratap 27/07/1986 470000008 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Singh One, District Hamirpur (HP) 38835 Usha Devi Nikka Ram 19/11/1989 470000009 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre One, District Hamirpur (HP) 106612 Sushma W/O Rajesh 9/10/1983 470000010 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kumari Kumar One, District Hamirpur (HP) 51251 PRAVEEN JAVAHIR 12/8/1993 470000011 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre YADAV SINGH YADAV One, District Hamirpur (HP) 37051 Suresh S/O Baldev 15/07/1983 470000012 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kumar Dass One, District Hamirpur (HP) 20316 Anju Devi D/O Suram 5/12/1988 470000013 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Singh One, District Hamirpur (HP) 51530 Sushma Govind Ram 13/04/1990 470000014 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kamal One, District Hamirpur (HP) 62270 Sharmila D/O Tulsi Ram 29/03/1985 470000015 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kumari One, District Hamirpur (HP) 24854 SANDEEP SH. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

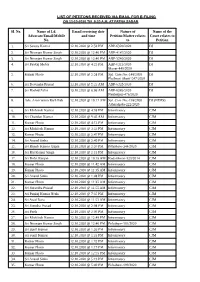

LIST of PETITONS RECEIVED VIA EMAIL for E-FILING Sl. No. Name

LIST OF PETITONS RECEIVED VIA EMAIL FOR E-FILING ON 13-10-2020 Till 9:30 A.M. AT PATNA SADAR Sl. No. Name of Ld. Email receiving date Nature of Name of the Advocate/Email/Mobile and time Petition/Matter relates Court relates to No. to Petition 1. Sri Sanjay Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 2:50 PM ABP-6320/2020 DJ 2. Sri Niranjan Kumar Singh 12.10.2020 @ 12:46 PM ABP-4187/2020 DJ 3. Sri Niranjan Kumar Singh 12.10.2020 @ 12:46 PM ABP-5240/2020 DJ 4. Sri Pankaj Mehta 12.10.2020 @ 4:23 PM ABP-6313/2020 DJ Maner-440/2020 5. Kumar Photo 12.10.2020 @ 5:58 PM Spl. Case No.-148/2020 DJ Phulwari Sharif-547/2020 6. Sri Devendra Prasad 13.10.2020 @ 5:22 AM ABP-6235/2020 DJ 7. Sri Rashid Zafar 13.10.2020 @ 6:06 AM ABP-6385/2020 DJ Naubatpur-476/2020 8. Adv. Association Barh Bab 12.10.2020 @ 10:17 AM Spl. Case No.-138/2020 DJ (NDPS) Athmalgola-222/2020 9. Sri Mithilesh Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 4:38 PM Informatory CJM 10. Sri Chandan Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 9:45 AM Informatory CJM 11. Kumar Photo 12.10.2020 @ 4:13 PM Informatory CJM 12. Sri Mithilesh Kumar 12.10.2020 @ 3:32 PM Informatory CJM 13. Kumar Photo 12.10.2020 @ 2:47 PM Informatory CJM 14. Sri Anand Sinha 12.10.2020 @ 2:40 PM Informatory CJM 15. Sri Rajesh Kumar Gupta 12.10.2020 @ 2:36 PM Pribahore-344/2020 CJM 16. -

Bihar Police Constable

Bihar Police Constable Online Form 2020 Central Selection Board of Constable CSBC Bihar Police Constable Recruitment 2020 Total 8415 Post Important Dates: Bihar Police Constable Form Start Date 13 November 2020 Bihar Consta ble 2020 Last Date 14 December 2020 CSBC Bihar Police Constable Last Date Payment 14 December 2020 Application Fees: • General / OBC / Other State : Rs. 450/- • SC / ST: Rs. 112/- Age Limit: • Age Calculate on 01 August 2020 • Minimum 18 Years & Maximum 25 Years Eligibility: • Intermediate in Any Stream from Any Recognized Board Vacancy Details: General EWS OBC EOBC OBC-Female SC ST Total 3489 842 980 1470 245 1307 82 8415 District Wise Vacancy Details: District Name Total Post District Name Total Post Patna 600 Madhubandi 40 Bhojpur 260 Saharsa 40 Kaimur 80 Madhepura 70 Aurangabad 100 Kishanganj 20 Jahanabad 80 Arriya 20 Muzaffarpur 400 Baka 250 Shivhar 20 Khagadiya 130 Betiyan 80 Begusarai 130 Saran 160 Lakhisarai 150 Gopalganj 100 Rail Patna 100 Bihar Military Police 01 Patna 248 Rail Katihar 100 B.R.O.S.B Patna 1206 Military Police Central Region 07 Central Area Patna 06 Horseman Military Police Ara 52 Tirhut Area, Muzaffapur 07 S.O.I.R.B. Bodhgaya 208 Punia Area 05 Magadh Area Gaya 05 Koshi Area Saharsha 15 Mithila Area Darbanga 09 Eastern Area Bhagalpur 14 Shahabad Area Dehari 02 Munger Area 08 Champaran Area Betiyan 12 Traffic Police H.Q. Patna 16 Begularsarai Area 06 Training H.Q. Patna 44 Bihar Police H.Q. Patna 90 Caste Department, Patna 40 Finance H.Q. Patna 20 State Other Backward Prosecution 44 Special Branch, Patna 468 Bureau Nalanda 240 Economic Offenses U nit , Patna 216 Rohtas 90 Supaul 70 Gaya 200 Purnia 230 Newada 250 Katihar 90 Arwal 06 Bhagalpur 90 Vaishali 150 Navgachiya 70 Sitamarhi 190 Munger 200 Motihari 80 Sekhpura 20 Siwan 100 Jamui 300 Darbangha 170 Rail Muzaffarpur 40 Samastipur 140 Military Police H.Q. -

He Order Passed by Hon'ble JAD-I & Hon'ble JAD-II

he Order passed by Hon’ble JAD-I & Hon’ble JAD-II on the mentionslips filed by Ld. Counsels through the e-mail [email protected] In view of the recent surge in the covid cases wherein a large number of Court staffs & officers including some of the Hon'ble Judges of this Court have become Covid- positive and that there has been a sizable cut in the strength of the emplyees for the present, the Ld. Counsels are requested to make mentioning of extremely urgent matters only . The cases already listed before a Bench may be mentioned before the Bench concerned. Since the e-filing portal is now available as such no permission for fresh filing is required, all mention- slips regarding fresh filing are therefore disposed of accordingly. Mentioning matters regarding urgent hearing of pending cases: Name of Adv. Name of Party Nature of Reasons for Remarks Sl.No. With Ph.No. Case Mentioning 03.08.2021 (From 12:00 Noon of 02.08.2021 to 12:00 Noon of 03.08.2021) Civil Matters 1. Devendra Kr. Rani Yadav CWJC No. Withdrawal. To be Listed Mob. No. Not legi- 6365/2020 for withdrawal ble 2. Manoj Kumar Mukund Bihari CWJC For setting aside the No Urgency 9801179773 1188/2021 order dt. 18.01.2020 passed by Respon- dent no. 3 without any base the peti- tioner is suffering from financial prob- lem kindly heard out of turn, but up till now the case has not been listed since long. 3. Alka Verma Kamal Kumar & CWJC IA for addition for No Urgency 9431078283 Ors.