How Modernist Film Refashions the Myth of Don Quixote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Quixote and Legacy of a Caricaturist/Artistic Discourse

Don Quixote and the Legacy of a Caricaturist I Artistic Discourse Rupendra Guha Majumdar University of Delhi In Miguel de Cervantes' last book, The Tria/s Of Persiles and Sigismunda, a Byzantine romance published posthumously a year after his death in 1616 but declared as being dedicated to the Count of Lemos in the second part of Don Quixote, a basic aesthetie principIe conjoining literature and art was underscored: "Fiction, poetry and painting, in their fundamental conceptions, are in such accord, are so close to each other, that to write a tale is to create pietoríal work, and to paint a pieture is likewise to create poetic work." 1 In focusing on a primal harmony within man's complex potential of literary and artistic expression in tandem, Cervantes was projecting a philosophy that relied less on esoteric, classical ideas of excellence and truth, and more on down-to-earth, unpredictable, starkly naturalistic and incongruous elements of life. "But fiction does not", he said, "maintain an even pace, painting does not confine itself to sublime subjects, nor does poetry devote itself to none but epie themes; for the baseness of lífe has its part in fiction, grass and weeds come into pietures, and poetry sometimes concems itself with humble things.,,2 1 Quoted in Hans Rosenkranz, El Greco and Cervantes (London: Peter Davies, 1932), p.179 2 Ibid.pp.179-180 Run'endra Guha It is, perhaps, not difficult to read in these lines Cervantes' intuitive vindication of the essence of Don Quixote and of it's potential to generate a plural discourse of literature and art in the years to come, at multiple levels of authenticity. -

2022 Spain: Spanish in the Land of Don Quixote

Please see the NOTICE ON PROGRAM UPDATES at the bottom of this sample itinerary for details on program changes. Please note that program activities may change in order to adhere to COVID-19 regulations. SPAIN: Spanish in the Land of Don Quixote™ For more than a language course, travel to Toledo, Madrid & Salamanca - the perfect setting for a full Spanish experience in Castilla-La Mancha. OVERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS On this program you will travel to three cities in the heart of Spain, all ★ with rich histories that bring a unique taste of the country with each stop. Improve your Spanish through Start your journey in Madrid, the Spanish capital. Then head to Toledo, language immersion ★ where your Spanish immersion will truly begin and will make up the Walk the historic streets of Toledo, heart of your program experience. Journey west to Salamanca, where known as "the city of three you'll find the third oldest European university and Cervantes' alma cultures" ★ mater. Finally, if you opt to stay for our Homestay Extension, you will live Visit some of Madrid's oldest in Toledo for a week with a local family and explore Almagro, home to restaurants on a tapas tours ★ one of the oldest open air theaters in the world. Go kayaking on the Alto Tajo River ★ Help to run a summer English language camp for Spanish 14-DAY PROGRAM Tuition: $4,399 children Service Hours: 20 ★ Stay an extra week and live with a June 25 – July 8, 2022 Language Hours: 35 Spanish family to perfect your + 7-NIGHT HOMESTAY (OPTIONAL) Max Group Size: 32 Spanish language skills (Homestay July 8 - July 15 Age Range: 14-19 Add 10 service hours add-on only) Add 20 language hours Student-to-Staff Ratio: 8-to-1 Add $1,699 tuition Airport: MAD experienceGLA.com | +1 858-771-0645 | @GLAteens DAILY BREAKDOWN Actual schedule of activities will vary by program session. -

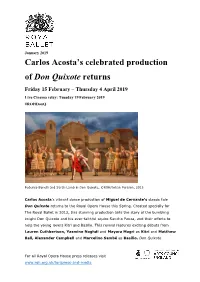

Don Quixote Press Release 2019

January 2019 Carlos Acosta’s celebrated production of Don Quixote returns Friday 15 February – Thursday 4 April 2019 Live Cinema relay: Tuesday 19 February 2019 #ROHDonQ Federico Bonelli and Sarah Lamb in Don Quixote, ©ROH/Johan Persson, 2013 Carlos Acosta’s vibrant dance production of Miguel de Cervante’s classic tale Don Quixote returns to the Royal Opera House this Spring. Created specially for The Royal Ballet in 2013, this stunning production tells the story of the bumbling knight Don Quixote and his ever-faithful squire Sancho Panza, and their efforts to help the young lovers Kitri and Basilio. This revival features exciting debuts from Lauren Cuthbertson, Yasmine Naghdi and Mayara Magri as Kitri and Matthew Ball, Alexander Campbell and Marcelino Sambé as Basilio. Don Quixote For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media includes a number of spectacular solos and pas de deux as well as outlandish comedy and romance as the dashing Basilio steals the heart of the beautiful Kitri. Don Quixote will be live streamed to cinemas on Tuesday 19 February as part of the ROH Live Cinema Season. Carlos Acosta previously danced the role of Basilio in many productions of Don Quixote. He was invited by Kevin O’Hare Director of The Royal Ballet, to re-stage this much-loved classic in 2013. Acosta’s vibrant production evokes sunny Spain with designs by Tim Hatley who has also created productions for the National Theatre and for musicals including Dreamgirls, The Bodyguard and Shrek. Acosta’s choreography draws on Marius Petipa’s 1869 production of this classic ballet and is set to an exuberant score by Ludwig Minkus arranged and orchestrated by Martin Yates. -

Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote?

From: Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America , 24.1 (2004): 173-88. Copyright © 2004, The Cervantes Society of America. Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote? MICHAEL MCGAHA t will probably never be possible to prove that Cervantes was a cristiano nuevo, but the circumstantial evidence seems compelling. The Instrucción written by Fernán Díaz de Toledo in the mid-fifteenth century lists the Cervantes family as among the many noble clans in Spain that were of converso origin (Roth 95). The involvement of Miguel’s an- cestors in the cloth business, and his own father Rodrigo’s profes- sion of barber-surgeon—both businesses that in Spain were al- most exclusively in the hand of Jews and conversos—are highly suggestive; his grandfather’s itinerant career as licenciado is so as well (Eisenberg and Sliwa). As Américo Castro often pointed out, if Cervantes were not a cristiano nuevo, it is hard to explain the marginalization he suffered throughout his life (34). He was not rewarded for his courageous service to the Spanish crown as a soldier or for his exemplary behavior during his captivity in Al- giers. Two applications for jobs in the New World—in 1582 and in 1590—were denied. Even his patron the Count of Lemos turn- 173 174 MICHAEL MCGAHA Cervantes ed down his request for a secretarial appointment in the Viceroy- alty of Naples.1 For me, however, the most convincing evidence of Cervantes’ converso background is the attitudes he displays in his work. I find it unbelievable that anyone other than a cristiano nuevo could have written the “Entremés del retablo de las maravi- llas,” for example. -

Don Quichotte Don Quixote Page 1 of 4 Opera Assn

San Francisco War Memorial 1990 Don Quichotte Don Quixote Page 1 of 4 Opera Assn. Opera House This presentation of "Don Quichotte" is made possible, in part, by a generous gift from Mr. & Mrs. Thomas Tilton Don Quichotte (in French) Opera in five acts by Jules Massenet Libretto by Henri Cain Based on play by Jacques Le Lorrain, based on Cervantes Conductor CAST Julius Rudel Pedro Mary Mills Production Garcias Kathryn Cowdrick Charles Roubaud † Rodriguez Kip Wilborn Lighting Designer Juan Dennis Petersen Joan Arhelger Dulcinée's Friend Michael Lipsky Choreographer Dulcinée Katherine Ciesinski Victoria Morgan Don Quichotte Samuel Ramey Chorus Director Sancho Pança Michel Trempont Ian Robertson The Bandit Chief Dale Travis Musical Preparation First Bandit Gerald Johnson Ernest Fredric Knell Second Bandit Daniel Pociernicki Susanna Lemberskaya First Servant Richard Brown Susan Miller Hult Second Servant Cameron Henley Christopher Larkin Svetlana Gorzhevskaya *Role debut †U.S. opera debut Philip Eisenberg Kathryn Cathcart PLACE AND TIME: Seventeenth-century Spain Prompter Philip Eisenberg Assistant Stage Director Sandra Bernhard Assistant to Mr. Roubaud Bernard Monforte † Supertitles Christopher Bergen Stage Manager Jamie Call Thursday, October 11 1990, at 8:00 PM Act I -- The poor quarter of a Spanish town Sunday, October 14 1990, at 2:00 PM INTERMISSION Thursday, October 18 1990, at 7:30 PM Act II -- In the countryside at dawn Saturday, October 20 1990, at 8:00 PM Act III -- The bandits' camp Tuesday, October 23 1990, at 8:00 PM INTERMISSION Friday, October 26 1990, at 8:00 PM Act IV -- The poor quarter Act V -- In the countryside at night San Francisco War Memorial 1990 Don Quichotte Don Quixote Page 2 of 4 Opera Assn. -

NI 7927-8 Book

NI 7927/8 NI 7927/8 Regiment of Sambre et Meuse should have been delayed until two months after the war had ended I do not know, but there is no gainsaying thepanache with which he trumpets forth his tribute to those intrepid military men. A comparison of these later recordings of Caruso’s with those made back in 1902 and 1903 PALESTRINA makes it evident how his voice had darkened and grown more massive over the years. The M I S S A O S A C R U M C O N V I V I U M advances in the recording process naturally emphasise this change, but in any case such was Caruso’s technical mastery that even when his voice was at its heaviest it never became unwieldy. His very last stage appearance was in a role which had been a favourite from his earliest days, Nemorino in L’elisir d’amore, which calls for great vocal dexterity; and anyone who doubts Caruso’s ability to sing rapidcoloratura in his latter days should listen to the cadenza at the end of his recording ofMia Piccirella from the operaSalvator Rosa, made in September 1919. I would like to end these reflections, though, with a glance at one more track from the current selection. This is the duet entitledCrucifix, written by the eminent French baritone Jean-Baptiste Faure, in which Caruso is partnered by Marcel Journet, one of the most celebrated basses of the day. Journet’s is the first voice that we hear, and very fine it is too; but when Caruso enters the sound is one of incomparable beauty, rich and majestic but astonishingly gentle too. -

The Universal Quixote: Appropriations of a Literary Icon

THE UNIVERSAL QUIXOTE: APPROPRIATIONS OF A LITERARY ICON A Dissertation by MARK DAVID MCGRAW Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Eduardo Urbina Committee Members, Paul Christensen Juan Carlos Galdo Janet McCann Stephen Miller Head of Department, Steven Oberhelman August 2013 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies Copyright 2013 Mark David McGraw ABSTRACT First functioning as image based text and then as a widely illustrated book, the impact of the literary figure Don Quixote outgrew his textual limits to gain near- universal recognition as a cultural icon. Compared to the relatively small number of readers who have actually read both extensive volumes of Cervantes´ novel, an overwhelming percentage of people worldwide can identify an image of Don Quixote, especially if he is paired with his squire, Sancho Panza, and know something about the basic premise of the story. The problem that drives this paper is to determine how this Spanish 17th century literary character was able to gain near-univeral iconic recognizability. The methods used to research this phenomenon were to examine the character´s literary beginnings and iconization through translation and adaptation, film, textual and popular iconography, as well commercial, nationalist, revolutionary and institutional appropriations and determine what factors made him so useful for appropriation. The research concludes that the literary figure of Don Quixote has proven to be exceptionally receptive to readers´ appropriative requirements due to his paradoxical nature. The Quixote’s “cuerdo loco” or “wise fool” inherits paradoxy from Erasmus of Rotterdam’s In Praise of Folly. -

MASSENET and HIS OPERAS Producing at the Average Rate of One Every Two Years

M A S S E N E T AN D HIS O PE RAS l /O BY HENRY FIN T. CK AU THO R O F ” ” Gr ie and His Al y sia W a ner and H W g , g is or ks , ” S uccess in Music and it W How is on , E ta , E tc. NEW YO RK : JO HN LANE CO MPANY MCMX LO NDO N : O HN L NE THE BO DLEY HE D J A , A K N .Y . O MP NY N E W Y O R , , P U B L I S HE R S P R I NTI N G C A , AR LEE IB R H O LD 8 . L RA Y BRIGHAM YO UNG UNlVERS lTW AH PRO VO . UT TO MY W I FE CO NTENTS I MASSENET IN AMER . ICA. H . B O GRAP KET H II I IC S C . P arents and Chi dhoo . At the Conservatoire l d . Ha D a n R m M rri ppy ys 1 o e . a age and Return to r H P a is . C oncert a Successes . In ar Time ll W . A n D - Se sational Sacred rama. M ore Semi religious m W or s . P ro e or and Me r of n i u k f ss be I st t te . P E R NAL R D III SO T AITS AN O P INIO NS . A P en P ic ure er en ne t by Servi es . S sitive ss to Griti m h cis . -

RCA Victor LCT 1 10 Inch “Collector's Series”

RCA Discography Part 28 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor LCT 1 10 Inch “Collector’s Series” The LCT series was releases in the Long Play format of material that was previously released only on 78 RPM records. The series was billed as the Collector’s Treasury Series. LCT 1 – Composers’ Favorite Intepretations - Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra [195?] Rosca: Recondita Amonia – Enrico Caruso/Madama Butterfly, Entrance of Butterfly – G. Farrar/Louise: Depuis Le Jour – M. Garden/Louise: Depuis Longtemps j’Habitais – E Johnson/Tosca: Vissi D’Arte – M. Jeritza/Der Rosenkavailier Da Geht ER Hin and Ich Werd Jetzt in Die Kirchen Geh’n – L Lehmann/Otello: Morte d’Otello – F. Tamagno LCT 2 – Caruso Sings Light Music – Enrico Caruso and Mischa Elman [195?] O Sole Mio/The Lost Chord/For You Alone/Ave Maria (Largo From "Xerxes")/Because/Élégie/Sei Morta Nella Vita Mia LCT 3 – Boris Goudnoff (Moussorgsky) – Feodor Chalipin, Albert Coates and Orchestra [1950] Coronation Scene/Ah, I Am Suffocating (Clock Scene)/I Have Attained The Highest Power/Prayer Of Boris/Death Of Boris LCT 4 LCT 5- Hamlet (Shakespeare) – Laurence Olivier with Philharmonia Orchestra [1950] O That This Too, Too Solid Flesh/Funeral March/To Be Or Not To Be/How Long Hast Thou Been Gravemaker/Speak The Speech/The Play Scene LCT 6 – Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 in G Minor Op. 63 (Prokofieff) – Jascha Heifetz and Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra [1950] LCT 7 – Haydn Symphony in G Major – Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra [195?] LCT 8 LCT 9 LCT 10 –Rosa Ponselle in Opera and Song – Rosa Ponselle [195?] La Vestale: Tu Che Invoco; O Nume Tutelar, By Spontini/Otello: Salce! Salce! (Willow Song); Ave Maria, By Verdi/Ave Maria, By Schubert/Home, Sweet Home, By Bishop LCT 11 – Sir Harry Lauder Favorites – Harry Lauder [195?] Romin' In The Gloamin'/Soosie Maclean/A Wee Deoch An' Doris/Breakfast In Bed On Sunday Morning/When I Met Mackay/Scotch Memories LCT 12 – Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. -

Fiction Excerpt 2: from the Adventures of Don Quixote

Fiction Excerpt 2: From The Adventures of Don Quixote (retold with excerpts from the novel by Miguel de Cervantes) Once upon a time, in a village in La Mancha, there lived a lean, thin-faced old gentleman whose favorite pastime was to read books about knights in armor. He loved to read about their daring exploits, strange adventures, bold rescues of damsels in distress, and intense devotion to their ladies. In fact, he became so caught up in the subject of chivalry that he neglected every other interest and even sold many acres of good farmland so that he might buy all the books he could get on the subject. He would lie awake at night, absorbed in every detail of these fantastic adventures. He would often engage in arguments with the village priest or the barber over who was the greatest knight of all time. Was it Amadis of Gaul or Palmerin of England? Or was it perhaps the Knight of the Sun? As time went on, the old gentleman crammed his head so full of these stories and lost so much sleep from reading through the night that he lost his wits completely. He began to believe that all the fantastic and romantic tales he read about enchantments, challenges, battles, wounds, and wooings were true histories. At last he fell into the strangest fancy that any madman has ever had: he resolved to become himself a knight errant, to travel through the world with horse and armor in search of adventures. First he got out some rust-eaten armor that had belonged to his ancestors, then cleaned and repaired it as best he could. -

"Gioconda" Rings Up-The Curtain At

Vol. XIX. No. 3 NEW YORK EDITED ~ ~ ....N.O.V.E.M_B_E_R_2_2 ,_19_1_3__ T.en.~! .~Ot.~:_:r.rl_::.: ... "GIOCONDA" RINGS "DON QUICHOTTE"HAS UP- THE CURTAIN AMERICANPREMIERE AT METROPOLITAN Well Performed by Chicago Com pany in Philadelphia- Music A Spirited Performance with Ca in Massenet's Familiar Vein ruso in Good 'Form at Head B ureau of Musical A m erica, of the Cas t~Amato, Destinn Sixt ee nth and Chestn ut Sts., Philadel phia, Novem ber 17. 1913.. and Toscanini at Their Best T HE first real novelty of the local opera Audience Plays Its Own Brilliant season was offered at the Metropolitan Part Brilliantly-Geraldine Far last Saturday afternoon, when Mas senet's "Don Quichotte" had its American rar's Cold Gives Ponchielli a premiere, under the direction of Cleofonte Distinction That Belonged to Campanini, with Vanni Marcoux in the Massenet title role, which he had sung many times in Europe; Hector Dufranne as Sancho W ITH a spirited performance of "Gio- Panza, and Mary Garden as La Belle Dul conda" the Metropolitan Opera cinea. The performance was a genuine Company began its season last M'o;day success. The score is in Massenet's fa night. The occasion was as brilliant as miliar vein: It offers a continuous flow of others that have gone before, and if it is melody, light, sometimes almost inconse quential, and not often of dramatic signifi not difficult to recall premieres of greater cance, but at all times pleasing, of an ele artistic pith and moment it behooves the gance that appeals to the aesthetic sense, chronicler of the august event to record and in all its phases appropriate to the the generally diffused glamor as a matter story, sketched rather briefly by Henri Cain from the voluminous romance of Miguel de of necessary convention, As us~al there Cervantes. -

Cervantes the Cervantes Society of America Volume Xxvi Spring, 2006

Bulletin ofCervantes the Cervantes Society of America volume xxvi Spring, 2006 “El traducir de una lengua en otra… es como quien mira los tapices flamencos por el revés.” Don Quijote II, 62 Translation Number Bulletin of the CervantesCervantes Society of America The Cervantes Society of America President Frederick De Armas (2007-2010) Vice-President Howard Mancing (2007-2010) Secretary-Treasurer Theresa Sears (2007-2010) Executive Council Bruce Burningham (2007-2008) Charles Ganelin (Midwest) Steve Hutchinson (2007-2008) William Childers (Northeast) Rogelio Miñana (2007-2008) Adrienne Martin (Pacific Coast) Carolyn Nadeau (2007-2008) Ignacio López Alemany (Southeast) Barbara Simerka (2007-2008) Christopher Wiemer (Southwest) Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America Editors: Daniel Eisenberg Tom Lathrop Managing Editor: Fred Jehle (2007-2010) Book Review Editor: William H. Clamurro (2007-2010) Editorial Board John J. Allen † Carroll B. Johnson Antonio Bernat Francisco Márquez Villanueva Patrizia Campana Francisco Rico Jean Canavaggio George Shipley Jaime Fernández Eduardo Urbina Edward H. Friedman Alison P. Weber Aurelio González Diana de Armas Wilson Cervantes, official organ of the Cervantes Society of America, publishes scholarly articles in Eng- lish and Spanish on Cervantes’ life and works, reviews, and notes of interest to Cervantistas. Tw i ce yearly. Subscription to Cervantes is a part of membership in the Cervantes Society of America, which also publishes a newsletter: $20.00 a year for individuals, $40.00 for institutions, $30.00 for couples, and $10.00 for students. Membership is open to all persons interested in Cervantes. For membership and subscription, send check in us dollars to Theresa Sears, 6410 Muirfield Dr., Greensboro, NC 27410.