ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

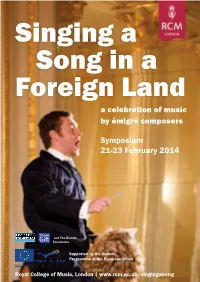

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

The Blue Review Literature Drama Art Music

Volume I Number III JULY 1913 One Shilling Net THE BLUE REVIEW LITERATURE DRAMA ART MUSIC CONTENTS Poetry Rupert Brooke, W.H.Davies, Iolo Aneurin Williams Sister Barbara Gilbert Cannan Daibutsu Yone Noguchi Mr. Bennett, Stendhal and the ModeRN Novel John Middleton Murry Ariadne in Naxos Edward J. Dent Epilogue III : Bains Turcs Katherine Mansfield CHRONICLES OF THE MONTH The Theatre (Masefield and Marie Lloyd), Gilbert Cannan ; The Novels (Security and Adventure), Hugh Walpole : General Literature (Irish Plays and Playwrights), Frank Swinnerton; German Books (Thomas Mann), D. H. Lawrence; Italian Books, Sydney Waterlow; Music (Elgar, Beethoven, Debussy), W, Denis Browne; The Galleries (Gino Severini), O. Raymond Drey. MARTIN SECKER PUBLISHER NUMBER FIVE JOHN STREET ADELPHI The Imprint June 17th, 1913 REPRODUCTIONS IN PHOTOGRAVURE PIONEERS OF PHOTOGRAVURE : By DONALD CAMERON-SWAN, F.R.P.S. PLEA FOR REFORM OF PRINTING: By TYPOCLASTES OLD BOOKS & THEIR PRINTERS: By I. ARTHUR HILL EDWARD ARBER, F.S.A. : By T. EDWARDS JONES THE PLAIN DEALER: VI. By EVERARD MEYNELL DECORATION & ITS USES: VI. By EDWARD JOHNSTON THE BOOK PRETENTIOUS AND OTHER REVIEWS: By J. H. MASON THE HODGMAN PRESS: By DANIEL T. POWELL PRINTING & PATENTS : By GEO. H. RAYNER, R.P.A. PRINTERS' DEVICES: By the Rev.T. F. DIBDIN. PART VI. REVIEWS, NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE. Price One Shilling net Offices: 11 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.G. JULY CONTENTS Page Post Georgian By X. Marcel Boulestin Frontispiece Love By Rupert Brooke 149 The Busy Heart By Rupert Brooke 150 Love's Youth By W. H. Davies 151 When We are Old, are Old By Iolo Aneurin Williams 152 Sister Barbara By Gilbert Cannan 153 Daibutsu By Yone Noguchi 160 Mr. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

Reviews of This Artist

Rezension für: Hertha Klust Pilar Lorengar: A portrait in live and studio recordings from 1959-1962 Vincenzo Bellini | Giacomo Puccini | Georg Friedrich Händel | Enrique Granados | Alessandro Scarlatti | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | Giuseppe Verdi | Joaquín Rodrigo | Joaquín Nin | Jesús García Leoz | Jesús Guridi | Eduardo Toldrà | _ Anonym | Jacobus de Milarte | Esteban Daza | Juan Bermudo | Luis de Narváez | Juan Vásquez | Alonso Mudarra | Luis de Milán | Diego Pisador | Enríquez de Valderrábano 3CD aud 21.420 operafresh.blogspot.de Tuesday, May 20, 2014 ( - 2014.05.20) Pilar Lorengar Live and Studio Recordings 1959-1962 Berlin In addition to the live opera recordings on this release, is the famous studio recording of songs with guitar featuring Siegfried Behrend available for the first time on CD outside of Japan. Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Das Opernglas Juni 2014 (J. Gahre - 2014.06.01) CD News Ihre Stimme [strahlt] in diesen um 1960 gemachten Aufnahmen Wärme und Weiblichkeit aus, die den modernen Hörer durchaus gefangen nehmen können. Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 96 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de http://theaterpur.net Juni 2014 (Christoph Zimmermann - 2014.06.01) Tenorales Gruppenbild mit Damen Pilar Lorengars klares, sonnenhelles Organ lässt nirgends falsche Sentimentalität aufkommen. [...] Neuerlich bezaubert die Natürlichkeit der Darstellung ohne ein demonstratives Ausstellen vokaler Raffinessen. Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Der Tagesspiegel 22.07.2014 (Frederik Hanssen - 2014.07.22) Klassik-CD der Woche: Pilar Lorengar Spanische Nächte Die Norma wie auch „Piangerò la sorte mia“ aus Händels „Giulio Cesare“ meistert sie mit Eleganz, jugendlicher Strahlkraft und schier endlosem Atem Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. -

40 JAHRE FRANZ-SCHUBERT-INSTITUT Internationaler Meisterkurs Für Liedinterpretation 2018Konzerte | Teilnehmer | Dozenten EHRENSCHUTZ KONZERTE 2018 Dipl

2010 40 JAHRE FRANZ-SCHUBERT-INSTITUT Internationaler Meisterkurs für Liedinterpretation 2018Konzerte | Teilnehmer | Dozenten EHRENSCHUTZ KONZERTE 2018 Dipl. Ing. Stefan Szirusek Termine 40 Jahre Schubertiaden in Baden LiederabendSa. 28. Juli, 17.00 Uhr Erstmals ohne den Badener Kulturpreisträger, Prof. Dr. Im Rahmen des Meisterkurses für Liedinterpretation Deen Larsen, der uns völlig Stift Heiligenkreuz, Kaisersaal überraschend im Jänner 2018 verlassen hat. Damit Eintritt frei, Spenden erbeten ist die Seele, der Motor und der Initiator dieser weltweit beachteten Ausbildungs- und Konzert- serie von uns gegangen. Seine Witwe, Verena Larsen, hat die Verantwortlichen der „Schubert- tage Baden“ um sich geschart um diese Kultur- schiene auf die Art und Weise, wie es Prof. Dr. FestkonzertMo. 30. Juli, 20.00 Uhr Deen Larsen angedacht hatte, weiterzuführen. 40 Jahre Franz-Schubert-Institut Ich wünsche dem neuen Team unter der Leitung von Vreni Larsen viel Erfolg und gutes Gelingen! in memoriam Dr. Deen Larsen Es musizieren Meisterlehrer und ehemalige Studenten Stadtpfarrkirche St. Stephan, Baden bei Wien Dipl. Ing. Stefan Szirucsek Eintritt frei, Spenden erbeten Bürgermeister www.schubert-institut.at 2 I Meisterkurs 2018 40 JAHRE SCHUBERT-INSTITUT Meisterkurs 2018 Im Herbst 1977 kam Deen Larsen von einem wenig erfolgreichen Sommerkurs für Liedinterpretation zurück, und beschloss "let's do it better, let's create our own master course". So fand im Sommer 1978 LiederabendSa. 28. Juli, 17.00 Uhr der erste Meisterkurs des Franz-Schubert-Institutes statt. Im Rahmen des Meisterkurses für Liedinterpretation Die Kernidee des Kurses, dem Wort und nender Energie suchte er auf vielen Rei- Stift Heiligenkreuz, Kaisersaal dem Gedicht das Hauptaugenmerk zu sen und Meisterkursen an den besten Eintritt frei, Spenden erbeten widmen, stieß bei den Größen der Lied- Musikuniversitäten auf der ganzen Welt kunst von Anfang an auf reges Interesse. -

Otello Program

GIUSEPPE VERDI otello conductor Opera in four acts Gustavo Dudamel Libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on production Bartlett Sher the play by William Shakespeare set designer Thursday, January 10, 2019 Es Devlin 7:30–10:30 PM costume designer Catherine Zuber Last time this season lighting designer Donald Holder projection designer Luke Halls The production of Otello was made possible by revival stage director Gina Lapinski a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr. The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 345th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S otello conductor Gustavo Dudamel in order of vocal appearance montano a her ald Jeff Mattsey Kidon Choi** cassio lodovico Alexey Dolgov James Morris iago Željko Lučić roderigo Chad Shelton otello Stuart Skelton desdemona Sonya Yoncheva This performance is being broadcast live on Metropolitan emilia Opera Radio on Jennifer Johnson Cano* SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Thursday, January 10, 2019, 7:30–10:30PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA Stuart Skelton in Chorus Master Donald Palumbo the title role and Fight Director B. H. Barry Sonya Yoncheva Musical Preparation Dennis Giauque, Howard Watkins*, as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello J. David Jackson, and Carol Isaac Assistant Stage Directors Shawna Lucey and Paula Williams Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Prompter Carol Isaac Italian Coach Hemdi Kfir Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Assistant Scenic Designer, Properties Scott Laule Assistant Costume Designers Ryan Park and Wilberth Gonzalez Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department; Angels the Costumiers, London; Das Gewand GmbH, Düsseldorf; and Seams Unlimited, Racine, Wisconsin Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses strobe effects. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1947-1950

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCH ESTRA MUSIC DIRECTOR. AT TANGLEWOOD 1948 « The Steinway is the1 official pian~ Arkansas Philharmonic «—— Buffalo Philharmonic Chattanooga Symphony Cleveland Orchestra Columbus Philharmonic Dallas Symphony Detroit Symphony Duluth Civic Symphony El Paso Symphony s'teinway . instrument of the Ft. Wayne Symphony Harrisburg Symphony immortals ! For excellence of Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles Houston Symphony workmanship, resonance of tone, responsiveness Indianapolis Symphony Kansas City Symphony to the player's touch, and durability of construction, Los Angeles Symphony Louisville Philharmonic the Steinway, from the smallest, lowest priced Miami Symphony Minneapolis Symphony vertical, grand, to the Steinway concert the Nat. Orchestral Assoc, of N.Y. Nat. Symphony, Wash., D.C. overwhelming choice of concert artists New Jersey Symphony New Orleans Civic Symphony and symphony orchestras, has no equal. It is New York Philharmonic Symphony Philadelphia Orchestra the recognized standard by which all other Pittsburgh Symphony Portland Symphony pianos are judged. It is the best . Robin Hood Dell Concerts, Phila. Rochester Symphony and you cannot afford anything but the best. St. Louis Symphony San Antonio Symphony Seattle Symphony Stadium Concerts, N. Y. City in Massachusetts and New Hampshire Syracuse Symphony Vancouver Symphony new Steinway pianos are sold ONLY by M'Steinert & Sons Jerome F. Murphy, President 162 Boylston St., Boston Branches in Worcester, Springfield and Wellesley Hills # * 'Serkshire Festival SEASON 1948 Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor CONCERT BULLETIN historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, I948, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Henry B. -

La Couleur Du Temps – the Colour of Time Salzburg Whitsun Festival 29 May – 1 June 2020

SALZBURGER FESTSPIELE PFINGSTEN Künstlerische Leitung: Cecilia Bartoli La couleur du temps – The Colour of Time Pauline Viardot-Garcia (1821 – 1910) Photo: Uli Weber - Decca Salzburg Whitsun Festival 29 May – 1 June 2020 (SF, 30 December 2019) The life of Pauline Viardot-Garcia – singer, musical ambassador of Europe, outstanding pianist and composer – is the focus of the 2020 programme of the Salzburg Whitsun Festival. “The uncanny instinct Cecilia Bartoli has for the themes of our times is proven once again by her programme for the 2020 Salzburg Whitsun Festival, which focuses on Pauline Viardot. Orlando Figes has just written a bestseller about this woman. Using Viardot as an example, he describes the importance of art within the idea of Europe,” says Festival President Helga Rabl-Stadler. 1 SALZBURGER FESTSPIELE PFINGSTEN Künstlerische Leitung: Cecilia Bartoli Pauline Viardot not only made a name for herself as a singer, composer and pianist, but her happy marriage with the French theatre manager, author and art critic Louis Viardot furthered her career and enabled her to act as a great patron of the arts. Thus, she made unique efforts to save the autograph of Mozart’s Don Giovanni for posterity. Don Giovanni was among the manuscripts Constanze Mozart had sold to Johann Anton André in Offenbach in 1799. After his death in 1842, his daughter inherited the autograph and offered it to libraries in Vienna, Berlin and London – without success. In 1855 her cousin, the pianist Ernst Pauer, took out an advertisement in the London-based journal Musical World. Thereupon, Pauline Viardot-García bought the manuscript for 180 pounds. -

Jack Lund Collection ARS.0045

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5w103784 No online items Guide to the Jack Lund Collection ARS.0045 Finding aid prepared by Frank Ferko Archive of Recorded Sound Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford University Stanford, California, 94305-3076 650-723-9312 [email protected] © 2011 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Jack Lund Collection ARS.0045 1 ARS.0045 Descriptive Summary Title: Jack Lund Collection Dates: 1887-2009 Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0045 Creator: Lund, Jack H. Collection size: 5345 items (570.33 linear ft.)Collection of disc recordings, tapes, books, magazines, programs, librettos, printed music and autographed programs and photographs. Repository: Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California 94305-3076 Abstract: The Jack Lund Collection contains personal papers of Jack Lund as well as numerous newspaper and magazine clippings, photographs, and music books. It also contains Lund's collection of classical music on 78 rpm discs, mostly in albums, 33 1/3 rpm long playing discs, and a small number of open reel tapes. The materials in this collection document the principal musical interests of Mr. Lund, i.e. vocal solo music, opera, careers and performances of specific singers and pianists, and the career of Arturo Toscanini. Since Mr. Lund mantained personal friendships with many musicians he admired, he acquired autographed photographs of these artists, and he regularly corresponded with them. The photographs and many of the letters from these musicians are included in the collection. As an avid reader of published articles and books on musical topics, Mr. -

ARSC Journal, Vol.21, No

Sound Recording Reviews Wagner: Parsifal (excerpts). Berlin State Opera Chorus and Orchestra (a) Bayreuth Festival Chorus and Orchestra (b), cond. Karl Muck. Opal 837/8 (LP; mono). Prelude (a: December 11, 1927); Act 1-Transformation & Grail Scenes (b: July/ August, 1927); Act 2-Flower Maidens' Scene (b: July/August, 1927); Act 3 (a: with G. Pistor, C. Bronsgeest, L. Hofmann; slightly abridged; October 10-11and13-14, 1928). Karl Muck conducted Parsifal at every Bayreuth Festival from 1901 to 1930. His immediate predecessor was Franz Fischer, the Munich conductor who had alternated with Hermann Levi during the premiere season of 1882 under Wagner's own supervi sion. And Muck's retirement, soon after Cosima and Siegfried Wagner died, brought another changing of the guard; Wilhelm Furtwangler came to the Green Hill for the next festival, at which Parsifal was controversially assigned to Arturo Toscanini. It is difficult if not impossible to tell how far Muck's interpretation of Parsifal reflected traditions originating with Wagner himself. Muck's act-by-act timings from 1901 mostly fall within the range defined in 1882 by Levi and Fischer, but Act 1 was decidedly slower-1:56, compared with Levi's 1:47 and Fischer's 1:50. Muck's timing is closer to that of Felix Mottl, who had been a musical assistant in 1882, and of Hans Knappertsbusch in his first and slowest Bayreuth Parsifal. But in later summers Muck speeded up to the more "normal" timings of 1:50 and 1:47, and the extensive recordings he made in 1927-8, now republished by Opal, show that he could be not only "sehr langsam" but also "bewegt," according to the score's requirements.