The Power and the Glory to Monsignor Quixote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{FREE} the Confidential Agent: an Entertainment

THE CONFIDENTIAL AGENT: AN ENTERTAINMENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graham Greene | 272 pages | 22 Jan 2002 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099286196 | English | London, United Kingdom The Confidential Agent: An Entertainment PDF Book Graham Greene. View all 3 comments. I am going to follow this up with The Heart of the Matter. Neil Forbes Holmes Herbert This edition published in by Viking Press in New York. This wistful romance is one of Greene's other masterstrokes of plotting; he is refreshingly unabashed about any pig-headed question of decency and he lets this romance flow in seamlessly and incidentally into the narrative to lend it a real heart of throbbing passion. Shipping to: Worldwide. Buy this book Better World Books. Seller information worldofbooksusa Not in Library. Clear your history. The confidential agent: an entertainment , The Viking Press. In a small continental country civil war is raging. It has a fast-moving plot, reversals of fortune, and plenty of action. It is not exactly foiling a diabolical conspiracy perpetuated by a grand, preening super-villain or sneaking behind enemy lines. Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? The Power And The Glory was a deliberate exercise in exploring religion and morality, and Greene did not expect it to sell very well. Edit Did You Know? Well, it is. So, despite a promising start and interesting plot, the story itself loses grip on a number of occasions because there is little chemistry, or tension, between the characters - not between D. So he writes this book in the mornings, then writes the "serious" novel in the afternoons; whilst helping dig trenches on London's commons with the war looming. -

Africa: La Herencia De Livingstone En a Burnt-Out Case, De Graham Greene Y El Sueño Del Celta, De Mario Vargas Llosa

ISSN: 0213-1854 'Civilizar' Africa: La herencia de Livingstone en A Burnt-Out Case, de Graham Greene y El sueño del celta, de Mario Vargas Llosa (‘Civilizing’ Africa: Livingstone’s Inheritance in A Burnt-Out Case, by Graham Greene and El sueño del celta, by Mario Vargas Llosa) BEATRIZ VALVERDE JIMÉNEZ [email protected] Universidad Loyola Andalucía Fecha de recepción: 8 de mayo de 2015 Fecha de aceptación: 1 de julio de 2015 Resumen: En este artículo usamos el concepto de „semiosfera‟ desarrollado por el estudioso ruso-estonio Juri Lotman para examinar las relaciones entre las comunidades nativas y las europeas en el Congo belga creadas por Graham Greene en A Burnt-Out Case y por Mario Vargas Llosa en El sueño del celta. Con este análisis tratamos de probar que aunque ambos autores denuncian con sus obras las terribles consecuencias de la colonización europea para los africanos, las comunidades nativas son descritas desde un punto de vista occidental y paternalista. Palabras clave: Congo. Colonización. Lotman. Semiosfera. Europeos. Africanos. Greene. Vargas Llosa. Abstract: In this article the concept of „semiosphere‟, developed by the Russian-Estonian scholar Juri Lotman, is used to examine the relationship between the African and the European communities in the Congo portrayed by Graham Greene in A Burnt-Out Case and by Mario Vargas Llosa in El sueño del celta. With this analysis I will prove that even though both authors denounce the terrible consequences of the European colonization had for the African people, the native communities in the novels are still depicted from a western paternalistic perspective. -

Graham Greene Exhibition Catalogue

The Cherry Record Collection of Josephine Reid’s Papers and Books Relating to Our thanks to the following donors who made the acquisition possible: Paul Almond (1949) GRAHAM GREENE Professor John Stephenson (1953) Professor John-Christopher Spender (1957) Roger Jefferies (1957) Paul Lewis (1958) Peter Buckman (1959) Matthew Nimetz (1960) Doug Rosenthal (1961) Alan James (1962) Stephen Crew (1964) Jim Rogers (1964) Emeritus Professor Paul Crittenden (1965) Alan Heeks (1966) Geoff Wright (1967) Neil Record (1972) Julie Record Richard Jones (1977) Mark Storey (1981) Danny Truell (1982) Alison Roberts (1984) Claire Foster-Gilbert (1984) Virginia Preston (1985) Richard Locke (1985) Jonathan Lewin (1992) Adam Dixon (1994) Sarah Longair (1998) Jo Valentine (2001) Jeff Kulkarni (2001) Sean McDaniel (2002) Alice McDaniel (2003) Blackwell Charitable Trust Friends of the National Libraries ISBN 978-1-78280-500-7 An exhibition held at BALLIOL COLLEGE HISTORIC COLLECTIONS CENTRE 9 781782 805007 > ST CROSS CHURCH, ST CROSS ROAD, OXFORD 25 & 26 April 2015 EXHIBITION AND CATALOGUE BY Naomi Tiley Librarian, Balliol College Anna Sander Archivist, Balliol College FOREWORD BY Sir Anthony Kenny Master of Balliol College 1978–1989 Seamus Perry COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Fellow Librarian, Balliol College Studio portrait of Josephine Reid taken in the late 1940s or early Neil Record 1950s. Photographer unknown. Balliol 1972 Handwriting © Josephine Reid’s Estate Details from postcards from Graham Greene to Josephine Reid © Verdant SA. The organisers are indebted to -

2022 Spain: Spanish in the Land of Don Quixote

Please see the NOTICE ON PROGRAM UPDATES at the bottom of this sample itinerary for details on program changes. Please note that program activities may change in order to adhere to COVID-19 regulations. SPAIN: Spanish in the Land of Don Quixote™ For more than a language course, travel to Toledo, Madrid & Salamanca - the perfect setting for a full Spanish experience in Castilla-La Mancha. OVERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS On this program you will travel to three cities in the heart of Spain, all ★ with rich histories that bring a unique taste of the country with each stop. Improve your Spanish through Start your journey in Madrid, the Spanish capital. Then head to Toledo, language immersion ★ where your Spanish immersion will truly begin and will make up the Walk the historic streets of Toledo, heart of your program experience. Journey west to Salamanca, where known as "the city of three you'll find the third oldest European university and Cervantes' alma cultures" ★ mater. Finally, if you opt to stay for our Homestay Extension, you will live Visit some of Madrid's oldest in Toledo for a week with a local family and explore Almagro, home to restaurants on a tapas tours ★ one of the oldest open air theaters in the world. Go kayaking on the Alto Tajo River ★ Help to run a summer English language camp for Spanish 14-DAY PROGRAM Tuition: $4,399 children Service Hours: 20 ★ Stay an extra week and live with a June 25 – July 8, 2022 Language Hours: 35 Spanish family to perfect your + 7-NIGHT HOMESTAY (OPTIONAL) Max Group Size: 32 Spanish language skills (Homestay July 8 - July 15 Age Range: 14-19 Add 10 service hours add-on only) Add 20 language hours Student-to-Staff Ratio: 8-to-1 Add $1,699 tuition Airport: MAD experienceGLA.com | +1 858-771-0645 | @GLAteens DAILY BREAKDOWN Actual schedule of activities will vary by program session. -

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

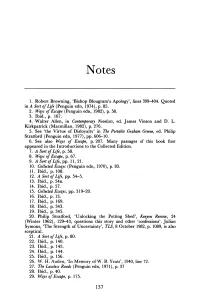

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

The Third Man"

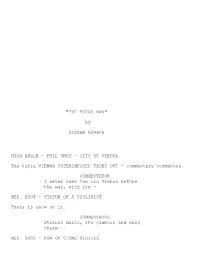

"THE THIRD MAN" by Graham Greene HIGH ANGLE - FULL SHOT - CITY OF VIENNA The title VIENNA SUPERIMPOSED FADES OUT - commentary commences. COMMENTATOR I never knew the old Vienna before the war, with its - MED. SHOT - STATUE OF A VIOLINIST There is snow on it. COMMENTATOR Strauss music, its glamour and easy charm... MED. SHOT - ROW OF STONE STATUES ornamenting the top of a building. In the b.g. the top of a stone archway. They are snow-sprinkled. COMMENTATOR Constantinople suited... MED. SHOT - SNOW-COVERED STATUE Trees in b.g. COMMENTATOR me better. I really got to know it in the... CLOSE SHOT - TWO MEN talking in the street. COMMENTATOR - classic period of the black... CLOSEUP - SUITCASE opens toward camera, revealing contents consisting of tins of food, shoes, etc. The hands of a man come in from f.g. to take something out. COMMENTATOR - market. We'd run anything... CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE standing side by side in the street. The person CL running hands through a pair of silk stockings. COMMENTATOR - if people wanted it enough. CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE A woman's hands CL wearing a wedding ring - a man's hands CR holding in RH two small cartons - hands them over to her in exchange for some notes which she hands him. COMMENTATOR - and had the money to pay. CLOSE SHOT - FIVE WRIST WATCHES on a man's wrist from which the coat sleeve is turned back. COMMENTATOR Of course a situation like that - LONG SHOT - CAPSIZED SHIP in shallow water with a drowned body floating on the water CR of it. -

Norman Macleod

Norman Macleod "This strange, rather sad story": The Reflexive Design of Graham Greene's The Third Man. The circumstances surrounding the genesis and composition of Gra ham Greene's The Third Man ( 1950) have recently been recalled by Judy Adamson and Philip Stratford, in an essay1 largely devoted to characterizing some quite unwarranted editorial emendations which differentiate the earliest American editions from British (and other textually sound) versions of The Third Man. It turns out that these are changes which had the effect of giving the American reader a text which (for whatever reasons, possibly political) presented the Ameri can and Russian occupation forces in Vienna, and the central charac ter of Harry Lime, and his dishonourable deeds and connections, in a blander, softer light than Greene could ever have intended; indeed, according to Adamson and Stratford, Greene did not "know of the extensive changes made to his story in the American book and now claims to be 'horrified' by them"2 • Such obscurely purposeful editorial meddlings are perhaps the kind of thing that the textual and creative history of The Third Man could have led us to expect: they can be placed alongside other more official changes (usually introduced with Greene's approval and frequently of his own doing) which befell the original tale in its transposition from idea-resuscitated-from-old notebook to story to treatment to script to finished film. Adamson and Stratford show that these approved and 'official' changes involved revisions both of dramatis personae and of plot, and that they were often introduced for good artistic or practical reasons. -

The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene (2003) - Not Even Past

The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene (2003) - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 0 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene (2003) Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the by Mathew J. Butler Confederacy” Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory (1940), the story of a fugitive “whisky priest” in 1930s Mexico, is a short, pathos-laden novel about religious persecution after the Mexican Revolution. The Catholic Church at that time was under attack for its considerable wealth and social control. The unnamed priest at the center of the novel is a complicated man, by no means a conventional hero, but his refusal to abandon the priesthood eventually endows him with a magnetic aura of spirituality, despite his many vices. May 06, 2020 Not all professional historians admire the novel, More from The Public Historian however. Some find it overly polemical, others even anachronistic, given that the story of a persecuted priest, written after Greene’s visit in March-April 1938, BOOKS coincided with President Cárdenas’s decision to end the long revolutionary campaign against the Church. It America for Americans: A History of is also rather curious that the most celebrated novel Xenophobia in the United States by about Mexican Catholicism during the Revolution was Erika Lee (2019) written by an English neophyte who was new to Mexico. Greene’s English prejudices give rise to the novel’s flaws. -

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene's 'Dark and Magical Heart

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ by Dorcas Wangui MA (Lancaster) BA (Lancaster) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 Wangui 1 Abstract Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ This study explores the ways in which Catholic images, statues, and icons haunt the fictional, spiritual wasteland of Greene’s writing, nicknamed ‘Greeneland’. It is also prompted by a real space, discovered by Greene during his 1938 trip to Mexico, which was subsequently fictionalised in The Power and the Glory (1940), and which he described as ‘a short cut to the dark and magical heart of faith’. This is a space in which modern notions of disenchantment meets a primal need for magic – or the miraculous – and where the presentation of concepts like ‘salvation’ are defamiliarised as savage processes that test humanity. This brutal nature of faith is reflected in the pagan aesthetics of Greeneland which focus on the macabre and heretical images of Christianity and how for Greene, these images magically transform the darkness of doubt into desperate redemption. As an amateur spy, playwright and screen writer Greene’s visual imagination was a strength to his work and this study will focus on how the visuality of Greene’s faith remains in dialogue with debates concerning the ‘liquidation of religion’ in society, as presented by Graham Ward. The thesis places Greene’s work in dialogue with other Catholic novelists and filmmakers, particularly in relation to their own visual-religious aesthetics, such as Martin Scorsese and David Lodge. -

Nesetrilovai Reflection1930s O

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Reflection of the 1930´s British Society in Graham Greene´s Brighton Rock Iva Nešetřilová Bachelor thesis 2017 Prohlašuji: Tuto práci jsem vypracovala samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využila, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byla jsem seznámena s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1 autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Souhlasím s prezenčním zpřístupněním své práce v Univerzitní knihovně. V Pardubicích dne 17.3.2017 Iva Nešetřilová Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Olga Roebuck, M.Litt. Ph.D. for giving me the opportunity to choose this topic, for her professional help, advice, and, especially, for the time she had spent when consulting my work. Annotation This paper examines and analyses the reflection of British Society in the novel Brighton Rock by Graham Green. The first part explores the situation in Britain around the 1930s, the period when the book was written and published, and briefly focuses on the changing landscape brought about by the Depression and aftermath of the First World War. The emphasis is confined mostly to how these changes affected the lower classes, and a brief description of what constitutes working class is provided. -

Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote?

From: Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America , 24.1 (2004): 173-88. Copyright © 2004, The Cervantes Society of America. Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote? MICHAEL MCGAHA t will probably never be possible to prove that Cervantes was a cristiano nuevo, but the circumstantial evidence seems compelling. The Instrucción written by Fernán Díaz de Toledo in the mid-fifteenth century lists the Cervantes family as among the many noble clans in Spain that were of converso origin (Roth 95). The involvement of Miguel’s an- cestors in the cloth business, and his own father Rodrigo’s profes- sion of barber-surgeon—both businesses that in Spain were al- most exclusively in the hand of Jews and conversos—are highly suggestive; his grandfather’s itinerant career as licenciado is so as well (Eisenberg and Sliwa). As Américo Castro often pointed out, if Cervantes were not a cristiano nuevo, it is hard to explain the marginalization he suffered throughout his life (34). He was not rewarded for his courageous service to the Spanish crown as a soldier or for his exemplary behavior during his captivity in Al- giers. Two applications for jobs in the New World—in 1582 and in 1590—were denied. Even his patron the Count of Lemos turn- 173 174 MICHAEL MCGAHA Cervantes ed down his request for a secretarial appointment in the Viceroy- alty of Naples.1 For me, however, the most convincing evidence of Cervantes’ converso background is the attitudes he displays in his work. I find it unbelievable that anyone other than a cristiano nuevo could have written the “Entremés del retablo de las maravi- llas,” for example. -

The Lawless Roads

The Lawless Roads The Lawless Roads. Graham Greene. 1409020517, 9781409020516. Random House, 2010. 2010. 240 pages In 1938 Graham Greene was commissioned to visit Mexico to discover the state of the country and its people in the aftermath of the brutal anti-clerical purges of President Calles. His journey took him through the tropical states of Chiapas and Tabasco, where all the churches had been destroyed or closed and the priests driven out or shot. The experiences were the inspiration for his acclaimed novel, The Power and the Glory. Pdf Download http://variationid.org/.InmBGHm.pdf The Power And The Glory. ISBN:9781409017431. 240 pages. During a vicious persecution of the clergy in Mexico, a worldly priest, the 'whisky priest', is on the run. With the police closing in, his routes of escape are being shut off. Oct 2, 2010. Fiction. Graham Greene Twenty-One Stories Travel journey Without Maps The Lawless Roads In Search of a Character Getting to Know the General Essays Collected Essays First published in Great Britain in 1969 by The Bodley Head Vintage Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V. The long and frequently quoted passage from Cardinal Newman which forms the motto to The Lawless Roads (the quarry for The Power and the Glory) makes the general point most clearly, ending: Greene gives the personal application on the third page of The Lawless Roads:. Abstract Assassination plots that have been devised against Catholic bishop Don Samuel Ruiz Garcia are discussed, and Ruiz Garcia is profiled. Ruiz Garcia has worked tirelessly in Mexico to promote human rights but has been asked by the Vatican to" retire" because.