The Terah Plexus: Testing the Righteousness of Abraham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

Heavenly Priesthood in the Apocalypse of Abraham

HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM The Apocalypse of Abraham is a vital source for understanding both Jewish apocalypticism and mysticism. Written anonymously soon after the destruction of the Second Jerusalem Temple, the text envisions heaven as the true place of worship and depicts Abraham as an initiate of the celestial priesthood. Andrei A. Orlov focuses on the central rite of the Abraham story – the scapegoat ritual that receives a striking eschatological reinterpretation in the text. He demonstrates that the development of the sacerdotal traditions in the Apocalypse of Abraham, along with a cluster of Jewish mystical motifs, represents an important transition from Jewish apocalypticism to the symbols of early Jewish mysticism. In this way, Orlov offers unique insight into the complex world of the Jewish sacerdotal debates in the early centuries of the Common Era. The book will be of interest to scholars of early Judaism and Christianity, Old Testament studies, and Jewish mysticism and magic. ANDREI A. ORLOV is Professor of Judaism and Christianity in Antiquity at Marquette University. His recent publications include Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Selected Studies in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Concealed Writings: Jewish Mysticism in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2011), and Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology (2011). Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139856430 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2013 HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM ANDREI A. ORLOV Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us. -

Isaac and Ishmael, 1985

This was the first High Holy Day sermon I delivered as the new young rabbi at UCSB Hillel in 1985. It was in many ways a classic “rabbinic school sermon,” full of textual analysis…and way too long. It was also a bold attempt to address the sensitive subject of the Arab-Israeli conflict; I remember seeing one of the prominent Jewish professors get up and walk out in the middle! (He has since become a dearly beloved friend). Issac and Ishmael 1985 Rosh HaShanah, UCSB Hillel This morning we read of the exile of Hagar and Ishmael, what the rabbis later called the most painful moment of Abraham’s life. The portion speaks to us directly in a way that it did not for hundreds of years, because the conflict between the children of Isaac, the Jews, and the children of Ishmael, the Arabs, has become the central fact of Jewish life in the second half of this century. The emotional strain of this conflict is par- ticularly terrible because, just as in the biblical story of Hagar and Ishmael, it is exceed- ingly difficult to sort out the rights and wrongs. In fact, it is difficult to escape the conclu- sion that--on certain levels--we, like Sarah, have morally compromised ourselves in this family conflict. The question which this text throws back at us year after year--and with particular vehemence in our generation--is: Can there be peace between Isaac and Ish- mael? Or was it necessary, is it necessary, for Abraham’s house to be broken apart? To most difficult questions, the textual tradition does not offer solution. -

Ibn Ḥabīb's Kitāb Al-Muḥabbar and Its Place in Early Islamic Historical Writing

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Department of World Languages, Literatures, Faculty Publications and Cultures 9-2018 Ibn Ḥabīb’s Kitāb al-MuḤabbar and its Place in Early Islamic Historical Writing Abed el-Rahman Tayyara Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clmlang_facpub Part of the Islamic Studies Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Tayyara, Abed el-Rahman, "Ibn Ḥabīb’s Kitāb al-MuḤabbar and its Place in Early Islamic Historical Writing" (2018). World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Faculty Publications. 145. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clmlang_facpub/145 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IBN HABIB’S KITAB AL-MUHABBAR AND ITS PLACE IN EARLY ISLAMIC HISTORICAL WRITING ABED EL-RAHMAN TAYYARA Cleveland State University Biographical evidence about Abu Ja'far Muhammad b. Habib (d. 860) is slim. Almost nothing is known about his father, and even the name ‘Habib’1 is believed to be associated with his mother. Al-Hashimi and al- Baghdadi are two nisbas attached to Ibn Habib, the first of which derives from his mother being a client (mawla) of a Hashimi family, and the second of which implies that Ibn Habib spent a considerable part of his life in Baghdad. -

25 Prophets of Islam

Like 5.2k Search Qul . Home Prayer Times Ask Qul TV The Holy Qur'an Library Video Library Audio Library Islamic Occasions About Pearl of Wisdom Library » Our Messengers » 25 Prophets of Islam with regards to Allah's verse in the 25 Prophets of Islam Qur'an: "Indeed Allah desires to repel all impurity from you... 25 Prophets of Islam said,?'Impunity IS doubt, and by Allah, we never doubt in our Lord. How many prophets did God send to mankind? This is a debated issue, but what we know is what God has told us in the Quran. God says he sent a prophet to every nation. He says: Imam Ja'far ibn Muhammad al-Sadiq “For We assuredly sent amongst every People a Messenger, (with the command): ‘Serve God, and eschew Evil;’ of the people were [as] some whom God guided, and some on whom Error became inevitably (established). So travel through the earth, and see what was the Ibid. p. 200, no. 4 end of those who denied (the Truth)” (Quran 16:36) This is because one of the principles by which God operates is that He will never take a people to task unless He has made clear to them what His expectations are. Article Source The Quran mentions the names of 25 prophets and indicates there were others. It says: “Of some messengers We have already told you the story; of others We have not; - and to Moses God spoke direct.” (Quran 4:164) We acknowledge that 'Our Messengers Way' by 'Harun Yahya' for providing the The Names of the 25 Prophets Mentioned are as follows: original file containing the 'Our Adam Messengers'. -

What Sarah Saw: Envisioning Genesis 21:9-10

WHAT SARAH SAW: ENVISIONING GENESIS 21:9-10 DAVID J. ZUCKER Sarah saw . [Ishmael] metzahek . She said to Abraham, 'Get rid of that slave-woman and her child' (Gen. 21:9-10). Sarah sees her husband's son Ishmael "laughing" or "playing." (The Hebrew word metzahek , has multiple meanings.) Sarah goes to Abraham and demands that he 'get rid of that slave-woman and her child .' This is a major turning point in Sarah's life. She is about to create havoc in Abraham's household. Taking the text at face value, just what did Sarah see? What provokes this reaction on her part? The Masoretic text simply says that Ishmael is laugh- ing/playing; the Septuagint, and some Christian translations add the words "with her son Isaac." Sarah seems to assume that Ishmael is interacting with (or, perhaps, reacting to) her own son Isaac. Yet, in this context it is not at all clear that Isaac is present, or that the laughter/playing actually is directed at – or about – him. This brief episode has much greater meaning to her than just a chance en- counter. Apparently, she sees something threatening – to her? to Isaac? to her connections with Isaac? to the whole wider family relationship? – and consequently she is willing to risk a serious confrontation with her husband Abraham to assuage her concerns. Sarah is so infuriated that she cannot even bring herself to mention the names of Hagar and Ishmael. Instead, she labels them as objects: that slave-woman and her child . The reason she gives for her demand centers on the question of inheritance. -

The Prophets Seth ( Shis ) Habil Kabil © Play & Learn Sabi Enos ( Anush ) Cainan Mahalaeed Jared ( Yarav ) Enoch ( H

ADAM + Eve 1 The Prophets Seth ( Shis ) Habil Kabil © Play & Learn Sabi Enos ( Anush ) www.playandlearn.org Cainan Mahalaeed Jared ( Yarav ) Enoch ( H. Idris ) Methusela Lamech Noah ( H. Nuh ) Shem Ham Yafis Kan’an (did not get on the Ark) Canaan Cush Nimrod 4 Arpachshad Iram Ghasir Samud Khadir Ubayd Masikh Asif Ubayd H.Salih Saleb Eber ( H. Hud )3 Pelag Rem Midian Serag Mubshakar Nahor Mankeel Terah H. Shuaib Abraham ( H. Ibrahim )5 Haran Nahor + HAGAR ( Hajarah ) + Sarah Ishmael ( H. Ishmael ) Nabit Yashjub 2 Ya’rub Lot (H. Lut) Bethul Tayrah Nahur Laban Rafqa + Isaac ( H. Ishaq ) Muqawwam 6 Udd ( Udad ) Lay’ah Rahil + Jacob ( H. Yaqob ) Isu Razih Maws H. Ayyub Adnan Ma’add Nizar Mudar Rabee’ah Inmar Iyad Joseph ( H. Yusuf ) Banyamin Yahuda Ifra’im 8 more 6 Ilyas Aylan Rahma + H. Ayyub Lavi Mudrika Tanijah Qamah Kahas Imran Khozema Hudhayl Moses (H. Musa) Kanana Asad Asadah Hawn Aaron (H. Haroun) Judah Nazar Malik Abd Manah Milkan Alozar Fakhkhakh Maleeh Yukhlad Meetha Eeshia Fahar ( Qoreish ) Yaseen David (H. Dawood) H. Ilyas Solomon (H. Sulayman) Ghalib Muharib Harith Asad Looi Taym H. Zakariya + Elisabeth Hanna + Imran Kaab Amir Saham Awf Mary (Bibi Mariam) H. Yahya (John) Murra Husaya Adiyy Jesus (H. Isa) Zemah Kilab Yaqdah Tym Farih Abdul Uzzah Nafel Sad Khattab Kab Amr UMAR FATIMA [The Second [One of the first Abu Qahafa Uthman Caliph] coverts to Islam] ABU BAKR Ubaydullah [The First Caliph] Talha Abdullah Hafsa [ Married to Muhammad Umm Kulthoom Aisha Asma the Prophet ] [Married the [Married to Umar [Married to [Married to second -

About This Volume Robert C

About This Volume Robert C. Evans Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick is often considered the greatest American novel—a vast epic that combines deep philosophy and high adventure as well as rich comedy and profound tragedy. Moby- Dick also offers a particularly diverse array of characters of various types, personalities, and ethnic backgrounds, and its styles are as varied as the people it depicts. Full of humorous dialects and idioms and brimming with probing, impassioned, poetic speeches, Melville’s novel explores the fascinating world of whale-hunting in the mid-nineteenth century, even as it also raises some of the most persistent questions about the purposes and meanings of human life. 7he ¿nal impact of the book—when enraged whale meets pursuing ship—is one of the most memorable episodes in all of American literature. 7he present volume examines Moby-Dick, the novel (references to Moby Dick the whale have no italics and no hyphen), from a variety of points of view. Indeed, a special focus of this volume involves the many different kinds of critical perspectives that can be—and have been—employed when examining Melville’s masterwork. In particular, the present volume emphasizes how the novel was received by many of its earlier readers; the variety of ways in which it can be interpreted by readers today; and a number of the most up-to-date approaches, such as ecocriticism and connections between Melville’s novel and modern art. 7he volume opens with an essay by -oseph &sicsila, author (among much else) of an important book concerning the “canonization” of literary classics in anthologies of American literature. -

The Animal Teacher in Daniel Quinn's Ishmael

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos 22 (2018), Seville, Spain. ISSN 1133-309-X, 305-325 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/REN.2018.i22.13 THE ANIMAL TEACHER IN DANIEL QUINN’S ISHMAEL DIANA VILLANUEVA ROMERO Universidad de Extremadura; GIECO, I. Franklin-UAH; CILEM-UEx Received 31 July 2018 Accepted 9 February 2019 KEYWORDS Quinn; Ishmael; animal literature; captivity; environmental literature; primates; fable; Holocaust. PALABRAS CLAVES Quinn; Ishmael; literatura de animales; cautividad; literatura ambiental; primates; fábula; Holocausto. ABSTRACT This article aims at offering an analysis of the animal protagonist of Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and the Spirit (1992) by American author Daniel Quinn as well as his environmental lesson. This book tells the story of the relationship between a human and an animal teacher, the telepathic gorilla Ishmael. Throughout their conversations some of the reasons behind the environmental crisis are discussed and the need for a shift in the Western paradigm is defended. Special attention is given throughout this artice to the gorilla’s acquisition of personhood, his Socratic method, his thorough lesson on animal and human captivity, and the timeless quality of a fable that continues resonating with many of the global attempts towards a more sustainable world. RESUMEN Este artículo pretende ofrecer un análisis del animal protagonista en Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and the Spirit (1992) del autor norteamericano Daniel Quinn, así como de su lección ambiental. Este libro cuenta la historia de la relación entre un humano y su maestro, el gorila telepático Ishmael. A través de sus conversaciones se discuten algunas de las razones de la crisis ambiental y se defiende la necesidad de un cambio en el paradigma occidental. -

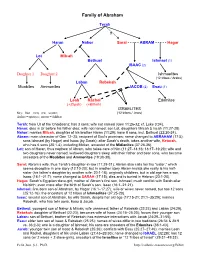

Family of Abraham

Family of Abraham Terah ? Haran Nahor Sarai - - - - - ABRAM - - - - - Hagar Lot Milcah Bethuel Ishmael (1) ISAAC (2) Daughter 1 Daughter 2 Ishmaelites (12 tribes / Arabs) Laban Rebekah Moabites Ammonites JACOB (2) Esau (1) Leah Rachel Edomites (+Zilpah) (+Bilhah) ISRAELITES Key: blue = men; red = women; (12 tribes / Jews) dashes = spouses; arrows = children Terah: from Ur of the Chaldeans; has 3 sons; wife not named (Gen 11:26-32; cf. Luke 3:34). Haran: dies in Ur before his father dies; wife not named; son Lot, daughters Milcah & Iscah (11:27-28). Nahor: marries Milcah, daughter of his brother Haran (11:29); have 8 sons, incl. Bethuel (22:20-24). Abram: main character of Gen 12–25; recipient of God’s promises; name changed to ABRAHAM (17:5); sons Ishmael (by Hagar) and Isaac (by Sarah); after Sarah’s death, takes another wife, Keturah, who has 6 sons (25:1-4), including Midian, ancestor of the Midianites (37:28-36). Lot: son of Haran, thus nephew of Abram, who takes care of him (11:27–14:16; 18:17–19:29); wife and two daughters never named; widowed daughters sleep with their father and bear sons, who become ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites (19:30-38). Sarai: Abram’s wife, thus Terah’s daughter-in-law (11:29-31); Abram also calls her his “sister,” which seems deceptive in one story (12:10-20); but in another story Abram insists she really is his half- sister (his father’s daughter by another wife; 20:1-18); originally childless, but in old age has a son, Isaac (16:1–21:7); name changed to SARAH (17:15); dies and is buried in Hebron (23:1-20). -

Inbreeding and the Origin of Races

JOURNAL OF CREATION 27(3) 2013 || PERSPECTIVES time, they would eventually come to population at that time, it should be Inbreeding and the same ancestor or set of ancestors clear that there couldn’t be a separate the origin of in both the mother and father’s side of ancestor in each place. And at 40 the family. This can be shown using generations (AD 810) you would have races simple mathematics. over 1 trillion ancestors, which is Simply count up the number of impossible since that is more people ancestors you have in preceding than have ever lived in the history of Robert W. Carter generations: 2 parents, 4 grand- the world. Almost all of your ances- parents, 8 great-grandparents, 16 tors that far back are your ancestors frequent question asked of great-great-grandparents, etc., and thousands of times over (or more) Acreationists is, “Where did the factor in that the average generation due to a process I call ‘genealogical different human races come from?” time for modern humans is about 30 recursion’. There are various ways to answer this years.4 Thus, 10 generations ago was Indeed, it does not take many gen- within the biblical (‘young-earth’) about AD 1710, and you had 1,024 erations to have more ancestral places paradigm and many articles and ancestors in that ‘generation’ (Of in your family tree than the popula- books have already been written course, not all of your ancestors lived tion of the world. The problem is made 1 on the subject. However, I recently at exactly the same time, but this is worse when you consider that many thought of a new way to illustrate a good estimate.) By 20 generations people do not leave any descendants.