The Gods Are Broken!: the Hidden Legacy of Abraham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prince William County Police Department Adult Arrests (Sorted By

Prince William County Police Department Adult Arrests (Sorted by Name) From: 06/15/2021 00:00:00 To: 07/15/2021 23:59:59 Arrest Date Sex DOB Age Name Residence Offense Descr 06/21/2021 00:00:00 M 04/12/1984 37 ABADJI, ROBERT KWABENA 2770 HAVERFORD LOOP APT 301 WOODBRIDGE, VA DRIVING: WHILE INTOXICATED/DUI - 90D LARCENY/THEFT: ALL OTHER - 23H OBSTRUCT JUSTICE: RESIST ARREST WITHOUT FORCE - 90Z DRIVING: FAILURE TO REPORT ACCIDENT/HIT AND RUN - 90Z MISDEMEANOR: ALL OTHER - 90Z DRIVING: REFUSAL OF TEST AND PROCEDURE DUI/DUID - 90Z 06/16/2021 00:00:00 F 04/24/2000 21 ADAMS, TYNIEA JANEE 3804 RUSSELL RD ALEXANDRIA, VA CHILD ABUSE: NEGLECT/NON-VIOLENT (NON PHYSICAL) - 90F DRUG: POSSESSION, INCLUDING IMITATION - 35A FAILURE TO APPEAR (FTA) - 90Z 07/11/2021 00:00:00 F 06/29/1981 40 AGBON-IFO, CHERIE 3565 EAGLE RIDGE DR WOODBRIDGE, VA DOMESTIC ASSAULT, SIMPLE - 13B 06/17/2021 00:00:00 M 09/21/1998 22 AGUELAR, HENRY 2870 GABLERIDGE TURN WOODBRIDGE, VA CONTEMPT OF COURT - 90Z MISDEMEANOR: ALL OTHER - 90Z 06/17/2021 00:00:00 M 09/29/1998 22 AGUELAR, HENRY NOE 2870 GABLERIDGE TURN APT 421 WOODBRIDGE, VA DRUG: POSSESSION, INCLUDING IMITATION - 35A OBSTRUCT JUSTICE: BY THREAT/FORCE - 13C GIVE FALSE INFORMATION TO POLICE - OBSTRUCTION - 26C 07/02/2021 00:00:00 F 10/19/1956 64 AGUILAR, MARIA LUISA 8657 BRUTON PARISH CT APT 112 MANASSAS, VA LARCENY/THEFT: ALTER PRICE TAGS - 26A 06/18/2021 00:00:00 M 04/29/1987 34 AHMED, MOHAMMAD 13086 PILGRIMS INN DR WOODBRIDGE, VA DOMESTIC ASSAULT, SIMPLE - 13B FAILURE TO APPEAR (FTA) - 90Z THREAT: BOMB - 13C DOMESTIC -

I C U: 35 Days to Revive My Faith

I C U: 35 Days to Revive My Faith Revelation 3:20 tells us that Jesus not only came to redeem us 2000 years ago, but every day pursues us - personally, persistently. Over the next 5 weeks, we will take a few minutes every day to open the door again to the work of God in our lives. Outside of the work on the cross and the empty tomb on the third day, God has given us another incredible gift: the gift of His word. It is through His word, the Bible, that God continues to speak, revive, and restore broken lives, dreams, and souls. I invite you to set aside 15 minutes, 5 days a week to open the door again to the work of God. Suggested daily outline: read 2 Timothy 3:16-17, pray, read the devotional, write a simple response to the devotional, and work on the weekly memory verse throughout the day ___________________ Week Five Sermon -- Making the Broken Pieces Fit: Dinah This week’s emphasis: Multiplying in Another (Coaching) Day One Read Luke 1:1-66 Elizabeth to Mary When you are “greatly troubled” do you have other believers you can open up to? Mary ran to Elizabeth, who was a truth teller in her life: “blessed are you!” Do you have someone in your life that can help you see the blessing through your troubles? It is important to find others who can lovingly walk through life with you, impart wisdom, truth, and remind you of God’s purpose and plan in your life, especially when you are under stress. -

Inmate Release Report Snapshot Taken: 9/28/2021 6:00:10 AM

Inmate Release Report Snapshot taken: 9/28/2021 6:00:10 AM Projected Release Date Booking No Last Name First Name 9/29/2021 6090989 ALMEDA JONATHAN 9/29/2021 6249749 CAMACHO VICTOR 9/29/2021 6224278 HARTE GREGORY 9/29/2021 6251673 PILOTIN MANUEL 9/29/2021 6185574 PURYEAR KORY 9/29/2021 6142736 REYES GERARDO 9/30/2021 5880910 ADAMS YOLANDA 9/30/2021 6250719 AREVALO JOSE 9/30/2021 6226836 CALDERON ISAIAH 9/30/2021 6059780 ESTRADA CHRISTOPHER 9/30/2021 6128887 GONZALEZ JUAN 9/30/2021 6086264 OROZCO FRANCISCO 9/30/2021 6243426 TOBIAS BENJAMIN 10/1/2021 6211938 ALAS CHRISTOPHER 10/1/2021 6085586 ALVARADO BRYANT 10/1/2021 6164249 CASTILLO LUIS 10/1/2021 6254189 CASTRO JAYCEE 10/1/2021 6221163 CUBIAS ERICK 10/1/2021 6245513 MYERS ALBERT 10/1/2021 6084670 ORTIZ MATTHEW 10/1/2021 6085145 SANCHEZ ARAFAT 10/1/2021 6241199 SANCHEZ JORGE 10/1/2021 6085431 TORRES MANLIO 10/2/2021 6250453 ALVAREZ JOHNNY 10/2/2021 6241709 ESTRADA JOSE 10/2/2021 6242141 HUFF ADAM 10/2/2021 6254134 MEJIA GERSON 10/2/2021 6242125 ROBLES GUSTAVO 10/2/2021 6250718 RODRIGUEZ RAFAEL 10/2/2021 6225488 SANCHEZ NARCISO 10/2/2021 6248409 SOLIS PAUL 10/2/2021 6218628 VALDEZ EDDIE 10/2/2021 6159119 VERNON JIMMY 10/3/2021 6212939 ADAMS LANCE 10/3/2021 6239546 BELL JACKSON 10/3/2021 6222552 BRIDGES DAVID 10/3/2021 6245307 CERVANTES FRANCISCO 10/3/2021 6252321 FARAMAZOV ARTUR 10/3/2021 6251594 GOLDEN DAMON 10/3/2021 6242465 GOSSETT KAMERA 10/3/2021 6237998 MOLINA ANTONIO 10/3/2021 6028640 MORALES CHRISTOPHER 10/3/2021 6088136 ROBINSON MARK 10/3/2021 6033818 ROJO CHRISTOPHER 10/3/2021 -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

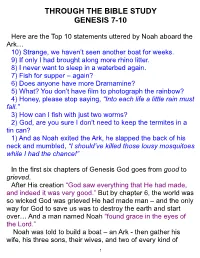

Noah Aboard the Ark… 10) Strange, We Haven’T Seen Another Boat for Weeks

THROUGH THE BIBLE STUDY GENESIS 7-10 Here are the Top 10 statements uttered by Noah aboard the Ark… 10) Strange, we haven’t seen another boat for weeks. 9) If only I had brought along more rhino litter. 8) I never want to sleep in a waterbed again. 7) Fish for supper – again? 6) Does anyone have more Dramamine? 5) What? You don’t have film to photograph the rainbow? 4) Honey, please stop saying, “Into each life a little rain must fall.” 3) How can I fish with just two worms? 2) God, are you sure I don’t need to keep the termites in a tin can? 1) And as Noah exited the Ark, he slapped the back of his neck and mumbled, “I should’ve killed those lousy mosquitoes while I had the chance!” In the first six chapters of Genesis God goes from good to grieved. After His creation “God saw everything that He had made, and indeed it was very good.” But by chapter 6, the world was so wicked God was grieved He had made man – and the only way for God to save us was to destroy the earth and start over… And a man named Noah “found grace in the eyes of the Lord.” Noah was told to build a boat – an Ark - then gather his wife, his three sons, their wives, and two of every kind of [1 animal on the earth. Noah was obedient… Which is where we pick it up tonight, chapter 7, “Then the LORD said to Noah, "Come into the ark, you and all your household, because I have seen that you are righteous before Me in this generation.” What a moving scene… When it’s time to board the Ark, God doesn’t tell Noah to go onto the ark, but to “come into the ark” – the implication is that God is onboard waiting for Noah. -

Heavenly Priesthood in the Apocalypse of Abraham

HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM The Apocalypse of Abraham is a vital source for understanding both Jewish apocalypticism and mysticism. Written anonymously soon after the destruction of the Second Jerusalem Temple, the text envisions heaven as the true place of worship and depicts Abraham as an initiate of the celestial priesthood. Andrei A. Orlov focuses on the central rite of the Abraham story – the scapegoat ritual that receives a striking eschatological reinterpretation in the text. He demonstrates that the development of the sacerdotal traditions in the Apocalypse of Abraham, along with a cluster of Jewish mystical motifs, represents an important transition from Jewish apocalypticism to the symbols of early Jewish mysticism. In this way, Orlov offers unique insight into the complex world of the Jewish sacerdotal debates in the early centuries of the Common Era. The book will be of interest to scholars of early Judaism and Christianity, Old Testament studies, and Jewish mysticism and magic. ANDREI A. ORLOV is Professor of Judaism and Christianity in Antiquity at Marquette University. His recent publications include Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Selected Studies in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Concealed Writings: Jewish Mysticism in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2011), and Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology (2011). Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139856430 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2013 HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM ANDREI A. ORLOV Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. -

Biblical Terror

Biblical Terror BIBLICAL TERROR Why Law and Restoration in the Bible Depend Upon Fear Jeremiah W. Cataldo T&T CLARK Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA BLOOMSBURY, T&T CLARK and the T&T Clark logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2017 Paperback edition fi rst published 2018 Copyright © Jeremiah W. Cataldo, 2017 Jeremiah W. Cataldo has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56767-081-6 PB: 978-0-56768-262-8 ePDF: 978-0-56767-082-3 ePUB: 978-0-56767-083-0 Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) To fi nd out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters. -

The PAS and American Abolitionism: a Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War

The PAS and American Abolitionism: A Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War By Richard S. Newman, Associate Professor of History Rochester Institute of Technology The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was the world's most famous antislavery group during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Indeed, although not as memorable as many later abolitionists (from William Lloyd Garrison and Lydia Maria Child to Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth), Pennsylvania reformers defined the antislavery movement for an entire generation of activists in the United States, Europe, and even the Caribbean. If you were an enlightened citizen of the Atlantic world following the American Revolution, then you probably knew about the PAS. Benjamin Franklin, a former slaveholder himself, briefly served as the organization's president. French philosophes corresponded with the organization, as did members of John Adams’ presidential Cabinet. British reformers like Granville Sharp reveled in their association with the PAS. It was, Sharp told told the group, an "honor" to be a corresponding member of so distinguished an organization.1 Though no supporter of the formal abolitionist movement, America’s “first man” George Washington certainly knew of the PAS's prowess, having lived for several years in the nation's temporary capital of Philadelphia during the 1790s. So concerned was the inaugural President with abolitionist agitation that Washington even shuttled a group of nine slaves back and forth between the Quaker State and his Mount Vernon home (still, two of his slaves escaped). The PAS was indeed a powerful abolitionist organization. PAS Origins The roots of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society date to 1775, when a group of mostly Quaker men met at a Philadelphia tavern to discuss antislavery measures. -

The Greatest Mirror: Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha

The Greatest Mirror Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha Andrei A. Orlov On the cover: The Baleful Head, by Edward Burne-Jones. Oil on canvas, dated 1886– 1887. Courtesy of Art Resource. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2017 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production, Dana Foote Marketing, Fran Keneston Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Orlov, Andrei A., 1960– author. Title: The greatest mirror : heavenly counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha / Andrei A. Orlov. Description: Albany, New York : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016052228 (print) | LCCN 2016053193 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438466910 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438466927 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Apocryphal books (Old Testament)—Criticism, interpretation, etc. Classification: LCC BS1700 .O775 2017 (print) | LCC BS1700 (ebook) | DDC 229/.9106—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016052228 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For April DeConick . in the season when my body was completed in its maturity, there imme- diately flew down and appeared before me that most beautiful and greatest mirror-image of myself. -

The Figure of Joseph the Patriarch in the New Testament and the Early Church

ABSTRACT “Much More Ours Than Yours”: The Figure of Joseph the Patriarch in the New Testament and the Early Church by John Lee Fortner This paper investigates the figure of Joseph the patriarch in early Christian interpretation, demonstrating the importance of such figures in articulating a Christian reading of the history of Israel, and the importance of this reading in the identity formation of early Christianity. The paper also illumines the debt of this Christian reading of Israel’s history to the work of Hellenistic Judaism. The figure of Joseph the patriarch is traced through early Christian interpretation, primarily from the Eastern Church tradition up to the 4th century C.E. The key methodological approach is an analysis of how the early church employed typological, allegorical, and moral exegesis in its construction of Joseph as a “Christian saint of the Old Testament.” A figure who, to borrow Justin Martyr’s phrase, became in the Christian identity “much more ours than yours.” “Much More Ours Than Yours”: The Figure of Joseph the Patriarch in the New Testament and the Early Church A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by John Lee Fortner Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2004 Advisor ________________________ Dr. Edwin Yamauchi Reader ________________________ Dr. Charlotte Goldy Reader _________________________ Dr. Wietse de Boer Table of Contents Introduction 1 Early Christian Hermeneutics 1 The Aura of Antiquity 6 Apologetics of Hellenistic Judaism 8 Scope and Purpose of Study 12 1. Joseph in the New Testament 13 Acts 7 14 Heb 11 15 2. -

Only the Righteous Escape God's Wrath

Through the Bible Series: Genesis Passage for This Week: Only the Righteous Escape Genesis 6:9-8:19 God’s Wrath Key Terms: Violence: The Hebrew Introduction: word is much broader than Were you one of those kids shaking under the blankets during a just murder. It is used to thunderstorm? Running and screaming to mom and dad when include unjust treatment lightning struck? Maybe you have had to hold a child and calm him (Gen 16:5; Amos 3:10), or her back to sleep during a torrential downpour. Imagine the anxiety in Noah’s heart, wondering if his pitch was strong enough to injurious legal testimony seal cypress against the strongest historical winds. Imagine telling (Deut 19:16), deadly Shem that he would live through twenty five more nights of thunder assault (Gen 49:5), and as the boat rocked another wave. How? By finding comfort in the rape (Jer 13:22). knowledge that God was near and had promised safety. Gopher Wood: This is a The Place of the Passage: transliteration of the God’s creation was marred by sin, and as the population grew so did Hebrew word. While the evil’s reach. Murder and immorality are introduced into society, and exact specie of tree is eventually God’s judgment comes swiftly. God only allows a few to survive the flood, but His covenant after the waters subside offers unknown, many modern blessing to the world’s future generations. translations render the term as “cypress” (e.g. NEB, NIV, NRSV). I. Primeval History: Creating for Blessing (1:11-11:26) A. -

Noah's Wife and Heterosexual Incestuous

Judaica Ukrainica I (2012), 29–46 No Name WomaN: Noah’s Wife aNd heterosexual iNcestuous relatioNs iN GeNesis 9:18–29 corinne e. Blackmer Southern Connecticut State University [email protected] [Noah’s wife] was a nameless woman, and so at home among all those who were never found and never missed, who were uncommemorated, whose deaths were not remarked, nor their begettings1. I. The terse language and riddling innuendo of Gen 9:18–29, which narrates how Noah comes to curse Canaan, the son of Ham, has engaged the inter pretive energies of readers since the rabbis of the Babylonian Talmud spe culated that Ham had castrated his father2. The language of this narrative, bristling with obscure phrases, loud hints of dreadful sexual transgression, and pious cover ups, has often left subsequent interpreters sensing that the story has meanings that the narrator declines to delineate. Indeed, the only thing that remains clear is that Gen 9:18–29 functions as an etiological myth to justify the permanent subordination of the tribes of Canaan. Canaan commits an un speakable sexual crime against Noah’s family that results in the subsequent physical displacement and sweeping rejection of the customs of the Canaanite peoples. Indeed, Israel’s secure possession of the Promised Land is predicated on repudiating the cultural institutions of the preceding Canaanites. Whatever the larger and associated issues, however, interpretive positions have gener 30 Corinne E. BLACKMER ally revolved around two broad questions. What was the nature of Ham’s of fense, such that when he “saw his father’s nakedness” and told his brothers, Shem and Japheth, it merited the terrible curse of permanent servitude Noah pronounced over him3? Second, what was the rationale for the punishment of Canaan and why, if Ham committed the crime, would his son Canaan suffer the penalty instead? Exegetical traditions have identified the deed for which Noah curses Ca naan either as voyeurism, castration, or homosexual paternal incest.