What Sarah Saw: Envisioning Genesis 21:9-10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us. -

Isaac and Ishmael, 1985

This was the first High Holy Day sermon I delivered as the new young rabbi at UCSB Hillel in 1985. It was in many ways a classic “rabbinic school sermon,” full of textual analysis…and way too long. It was also a bold attempt to address the sensitive subject of the Arab-Israeli conflict; I remember seeing one of the prominent Jewish professors get up and walk out in the middle! (He has since become a dearly beloved friend). Issac and Ishmael 1985 Rosh HaShanah, UCSB Hillel This morning we read of the exile of Hagar and Ishmael, what the rabbis later called the most painful moment of Abraham’s life. The portion speaks to us directly in a way that it did not for hundreds of years, because the conflict between the children of Isaac, the Jews, and the children of Ishmael, the Arabs, has become the central fact of Jewish life in the second half of this century. The emotional strain of this conflict is par- ticularly terrible because, just as in the biblical story of Hagar and Ishmael, it is exceed- ingly difficult to sort out the rights and wrongs. In fact, it is difficult to escape the conclu- sion that--on certain levels--we, like Sarah, have morally compromised ourselves in this family conflict. The question which this text throws back at us year after year--and with particular vehemence in our generation--is: Can there be peace between Isaac and Ish- mael? Or was it necessary, is it necessary, for Abraham’s house to be broken apart? To most difficult questions, the textual tradition does not offer solution. -

25 Prophets of Islam

Like 5.2k Search Qul . Home Prayer Times Ask Qul TV The Holy Qur'an Library Video Library Audio Library Islamic Occasions About Pearl of Wisdom Library » Our Messengers » 25 Prophets of Islam with regards to Allah's verse in the 25 Prophets of Islam Qur'an: "Indeed Allah desires to repel all impurity from you... 25 Prophets of Islam said,?'Impunity IS doubt, and by Allah, we never doubt in our Lord. How many prophets did God send to mankind? This is a debated issue, but what we know is what God has told us in the Quran. God says he sent a prophet to every nation. He says: Imam Ja'far ibn Muhammad al-Sadiq “For We assuredly sent amongst every People a Messenger, (with the command): ‘Serve God, and eschew Evil;’ of the people were [as] some whom God guided, and some on whom Error became inevitably (established). So travel through the earth, and see what was the Ibid. p. 200, no. 4 end of those who denied (the Truth)” (Quran 16:36) This is because one of the principles by which God operates is that He will never take a people to task unless He has made clear to them what His expectations are. Article Source The Quran mentions the names of 25 prophets and indicates there were others. It says: “Of some messengers We have already told you the story; of others We have not; - and to Moses God spoke direct.” (Quran 4:164) We acknowledge that 'Our Messengers Way' by 'Harun Yahya' for providing the The Names of the 25 Prophets Mentioned are as follows: original file containing the 'Our Adam Messengers'. -

About This Volume Robert C

About This Volume Robert C. Evans Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick is often considered the greatest American novel—a vast epic that combines deep philosophy and high adventure as well as rich comedy and profound tragedy. Moby- Dick also offers a particularly diverse array of characters of various types, personalities, and ethnic backgrounds, and its styles are as varied as the people it depicts. Full of humorous dialects and idioms and brimming with probing, impassioned, poetic speeches, Melville’s novel explores the fascinating world of whale-hunting in the mid-nineteenth century, even as it also raises some of the most persistent questions about the purposes and meanings of human life. 7he ¿nal impact of the book—when enraged whale meets pursuing ship—is one of the most memorable episodes in all of American literature. 7he present volume examines Moby-Dick, the novel (references to Moby Dick the whale have no italics and no hyphen), from a variety of points of view. Indeed, a special focus of this volume involves the many different kinds of critical perspectives that can be—and have been—employed when examining Melville’s masterwork. In particular, the present volume emphasizes how the novel was received by many of its earlier readers; the variety of ways in which it can be interpreted by readers today; and a number of the most up-to-date approaches, such as ecocriticism and connections between Melville’s novel and modern art. 7he volume opens with an essay by -oseph &sicsila, author (among much else) of an important book concerning the “canonization” of literary classics in anthologies of American literature. -

The Animal Teacher in Daniel Quinn's Ishmael

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos 22 (2018), Seville, Spain. ISSN 1133-309-X, 305-325 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/REN.2018.i22.13 THE ANIMAL TEACHER IN DANIEL QUINN’S ISHMAEL DIANA VILLANUEVA ROMERO Universidad de Extremadura; GIECO, I. Franklin-UAH; CILEM-UEx Received 31 July 2018 Accepted 9 February 2019 KEYWORDS Quinn; Ishmael; animal literature; captivity; environmental literature; primates; fable; Holocaust. PALABRAS CLAVES Quinn; Ishmael; literatura de animales; cautividad; literatura ambiental; primates; fábula; Holocausto. ABSTRACT This article aims at offering an analysis of the animal protagonist of Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and the Spirit (1992) by American author Daniel Quinn as well as his environmental lesson. This book tells the story of the relationship between a human and an animal teacher, the telepathic gorilla Ishmael. Throughout their conversations some of the reasons behind the environmental crisis are discussed and the need for a shift in the Western paradigm is defended. Special attention is given throughout this artice to the gorilla’s acquisition of personhood, his Socratic method, his thorough lesson on animal and human captivity, and the timeless quality of a fable that continues resonating with many of the global attempts towards a more sustainable world. RESUMEN Este artículo pretende ofrecer un análisis del animal protagonista en Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and the Spirit (1992) del autor norteamericano Daniel Quinn, así como de su lección ambiental. Este libro cuenta la historia de la relación entre un humano y su maestro, el gorila telepático Ishmael. A través de sus conversaciones se discuten algunas de las razones de la crisis ambiental y se defiende la necesidad de un cambio en el paradigma occidental. -

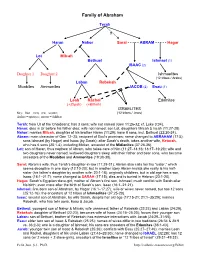

Family of Abraham

Family of Abraham Terah ? Haran Nahor Sarai - - - - - ABRAM - - - - - Hagar Lot Milcah Bethuel Ishmael (1) ISAAC (2) Daughter 1 Daughter 2 Ishmaelites (12 tribes / Arabs) Laban Rebekah Moabites Ammonites JACOB (2) Esau (1) Leah Rachel Edomites (+Zilpah) (+Bilhah) ISRAELITES Key: blue = men; red = women; (12 tribes / Jews) dashes = spouses; arrows = children Terah: from Ur of the Chaldeans; has 3 sons; wife not named (Gen 11:26-32; cf. Luke 3:34). Haran: dies in Ur before his father dies; wife not named; son Lot, daughters Milcah & Iscah (11:27-28). Nahor: marries Milcah, daughter of his brother Haran (11:29); have 8 sons, incl. Bethuel (22:20-24). Abram: main character of Gen 12–25; recipient of God’s promises; name changed to ABRAHAM (17:5); sons Ishmael (by Hagar) and Isaac (by Sarah); after Sarah’s death, takes another wife, Keturah, who has 6 sons (25:1-4), including Midian, ancestor of the Midianites (37:28-36). Lot: son of Haran, thus nephew of Abram, who takes care of him (11:27–14:16; 18:17–19:29); wife and two daughters never named; widowed daughters sleep with their father and bear sons, who become ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites (19:30-38). Sarai: Abram’s wife, thus Terah’s daughter-in-law (11:29-31); Abram also calls her his “sister,” which seems deceptive in one story (12:10-20); but in another story Abram insists she really is his half- sister (his father’s daughter by another wife; 20:1-18); originally childless, but in old age has a son, Isaac (16:1–21:7); name changed to SARAH (17:15); dies and is buried in Hebron (23:1-20). -

The Binding of Ishmael: Autobiographical Consciousness and Tragedy in Moby-Dick

THE BINDING OF ISHMAEL: AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL CONSCIOUSNESS AND TRAGEDY IN MOBY-DICK by Christopher Rice Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2014 © Copyright by Christopher Rice, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................iii AWKNOWLEDGEMENTS...............................................................................................iv CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION.................................................................................1 CHAPTER TWO MELVILLE'S BACKGROUND: READING AND WRITING EXPERIENCE....................................................................................11 CHAPTER THREE ISHMAEL'S AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL CONSCIOUSNESS........24 CHAPTER FOUR SUBJECTIVITY ON LAND; RECOLLECTION AND VISION...50 CHAPTER FIVE IN AWE; THE TRAGEDY OF AHAB..............................................77 CHAPTER SIX CONCLUSION...................................................................................125 BIBLIOGRAPHY............................................................................................................129 ii ABSTRACT Since its publication in 1851, Herman Melville's Moby-Dick has been difficult to pin down in any formal sense. The book's experimental style, which seems to violate literary conventions through Ishmael's immediate presence and subsequent "disappearance" in the Ahab drama, constitutes a significant -

Moses / Jesus / Muhammad Are Descendents of Abraham

Where Do You Stand? Abdul Hye, PhD 281-488-3191 [email protected] Descendents of Abraham Adam Noah Abraham 1900 BC Issac Ishmael Torah Hinduism 1500 BC Moses . Judaism 1300 BC Bible Buddhism 525 BC Jesus Christ Christianity 4 BC Quran Muhammad Islam 610 AD 2003 AD World Population Growth based on Last 50 Years* (in millions) Years Item Change* 2002 2010 2015 Christian 1.00% 2100 2274 2390 Comparative Chart Muslim 2.90% 1700 2137 2465 (Based on Last 50 Years) Jew -0.10% 15 15 15 Year Christian Muslim Hindu 2.10% 820 968 1074 1900 27% 12% Buddhist 1.20% 370 407 432 2000 30% 19% Sikh 2.00% 25 29 32 2005 29% 21% Confucianist -0.25% 320 314 310 2010 28% 23% Shintoist 2.10% 70 83 92 2015 26% 26% Others** 2.10% 800 945 1048 World 2.30% 6220 7171 7858 2020 26% 27% **African, Communist, non-religious, etc 2025 25% 30% (c) Madina Masjid, Houston, Texas 3 World Muslim Population World Muslim USA Population (280 m) Population 84% Christians (235 m) 18% Arabs 82% Non-Arabs 3.7% Muslims (10 m) 20% Africa 2.1% Jews (6 m) 10% Russia & China 10.2% Others (30 m) 17% South East Asia 30% India Subcontinent Islam 2nd Largest Religion 13% other places of World . % Muslim 10% Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan USA 3.7% UK 4% Canada 2% The majority of all France 7% Muslims are not Arab Germany 3.5% World Muslim Population Summary Islam is the fastest growing religion in the world. Every 4th person in the world is a MUSLIM. -

A Study of Michael, the Archangel

"From the cowardice that shrinks from new truth, from the laziness that is content with half truths, from the arrogance that thinks it knows all truth, O, God of Truth, deliver us." A Controversial Newsletter “The Printed Voice of Summit Theological Seminary” ~ All articles are written by George L. Faull, Rel. D. unless otherwise stated ~ Vol. 27 No. 1 January 2014 George L. Faull, Editor A Study of Eyes like flame…Omniscient. Feet like fine brass…Power and judgment. Michael, Voice like a sound of many waters, which John says elsewhere represents a great multitude of people. the Archangel This does not describe an archangel in either Daniel or What did the founders of the Jehovah Revelation; they are describing the same person. But the angel Witnesses, the Seventh Day Adventist, who talked to Daniel after his vision of "the certain man" tells John Wesley, John Calvin, Jonathan Daniel that he was hindered by the angel of Persia but that Edwards, Charles Spurgeon all have in Michael the Great Prince of Israel came to help him and the only common? They all believed that Jesus one that could help him was "Michael YOUR prince". Verse 13 was Michael the Archangel and stated so and verse 21. Note Michael did not himself appear to Daniel, nor in their writings. Many of the old Calvinistic commentaries in the chapter except he was spoken about by the angel who advocate this heresy. The doctrine is not true. spoke to Daniel after his vision of the Lord. So this chapter gives no credence to the heresy. -

Ishmael's Assassination of Gedaliah: Echoes of the Saul-David Story in Jeremiah 40:7-41:18 Gary E

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate Faculty Publications and Presentations School Spring 2005 Ishmael's Assassination of Gedaliah: Echoes of the Saul-David Story in Jeremiah 40:7-41:18 Gary E. Yates Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Yates, Gary E., "Ishmael's Assassination of Gedaliah: Echoes of the Saul-David Story in Jeremiah 40:7-41:18" (2005). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 8. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate School at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WT767(2005): 103-12 BIBLICAL STUDIES ISHMAEL'S ASSASSINATION OF GEDAIIAH: ECHOES OF THE SAUI^DAVID STORY IN JEREMIAH 40:7-41:18 GARY E. YKTES When one reads the book of Jeremiah, it might appear as if the account of Ishmael ben Nethaniah's assassination of Gedaliah, the governor of Judah, in Jer 40-41 is nothing more than a tragic footnote or addendum to the story of the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians. Both Ishmael and Gedaliah are rather minor figures in the history of ancient Israel who appear only briefly on the pages of the Hebrew Bible.1 Nevertheless, the narrator of Jer 40-41 provides a much more detailed record of the events surrounding Ishmael and Gedaliah than the parallel account in 2 Kgs 25:22-26.2 In addition, the narrator in Jeremiah infuses Gary E. -

21 U.S.C. § 841 21 U.S.C. § 846 ILEANA SANCHEZ, A/K/ a "Lilly," A/K/A "Marni"

Case 3:18-cr-00138-FLW Document 147 Filed 03/22/18 Page 1 of 12 PageID: 70 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Crim. No. 18-______ V. 21 u.s.c. § 841 21 u.s.c. § 846 ILEANA SANCHEZ, a/k/ a "Lilly," a/k/a "Marni" INDICTMENT The Grand Jury in and for the District of New Jersey, sitting at Trenton, charges: COUNT ONE (Conspiracy to Distribute and Possess With Intent to Distribute 100 Grams or More of Heroin) 1. At all times relevant to Count One of this Indictment: a. The defendant, ILEANA SANCHEZ, a/k/a "Lilly," a/k/a "Marni," resided in or around Trenton, New Jersey, and was engaged in the distribution of heroin for profit. b. Co-conspirator JOSE JOAQUIN TORRES-MEZQUITA, a/k/ a "Alex," a/k/ a "Papi," a/k/ a "Pop," a/k/ a "Pa" (hereafter, "TORRES"), resided in or around Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was in engaged in the distribution of heroin for profit. c. Co-conspirator ISHMAEL ABDULLAH, a/k/ a "lsh," a/k/a "Gangsta," a/k/a "Pop," resided in or around Trenton, New Jersey, and was engaged in the distribution of heroin for profit. ISHMAEL ABDULLAH was the leader of a drug-trafficking organization, hereafter referred to as 1 Case 3:18-cr-00138-FLW Document 147 Filed 03/22/18 Page 2 of 12 PageID: 71 the "Abdullah DTO," which was engaged in, among other things, the distribution of heroin for profit in and around Trenton, New Jersey.