USP48 Governs Cell Cycle Progression by Regulating the Protein Level of Aurora B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

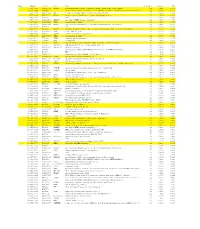

Supplementary Table 1. List of Genes Up-Regulated in Abiraterone-Resistant Vcap Xenograft Samples PIK3IP1 Phosphoinositide-3-Kin

Supplementary Table 1. List of genes up-regulated in abiraterone-resistant VCaP xenograft samples PIK3IP1 phosphoinositide-3-kinase interacting protein 1 TMEM45A transmembrane protein 45A THBS1 thrombospondin 1 C7orf63 chromosome 7 open reading frame 63 OPTN optineurin FAM49A family with sequence similarity 49, member A APOL4 apolipoprotein L, 4 C17orf108|LOC201229 chromosome 17 open reading frame 108 | hypothetical protein LOC201229 SNORD94 small nucleolar RNA, C/D box 94 PCDHB11 protocadherin beta 11 RBM11 RNA binding motif protein 11 C6orf225 chromosome 6 open reading frame 225 KIAA1984|C9orf86|TMEM14 1 KIAA1984 | chromosome 9 open reading frame 86 | transmembrane protein 141 KIAA1107 TLR3 toll-like receptor 3 LPAR6 lysophosphatidic acid receptor 6 KIAA1683 GRB10 growth factor receptor-bound protein 10 TIMP2 TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 2 CCDC28A coiled-coil domain containing 28A FBXL2 F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 2 NOV nephroblastoma overexpressed gene TSPAN31 tetraspanin 31 NR3C2 nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 2 DYNC2LI1 dynein, cytoplasmic 2, light intermediate chain 1 C15orf51 dynamin 1 pseudogene SAMD13 sterile alpha motif domain containing 13 RASSF6 Ras association (RalGDS/AF-6) domain family member 6 ZNF167 zinc finger protein 167 GATA2 GATA binding protein 2 NUDT7 nudix (nucleoside diphosphate linked moiety X)-type motif 7 DNAJC18 DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 18 SNORA57 small nucleolar RNA, H/ACA box 57 CALCOCO1 calcium binding and coiled-coil domain 1 RLN2 relaxin 2 ING4 inhibitor of -

Skp-Cullin-F Box E3 Ligase Component FBXL2 Ubiquitinates Aurora B to Inhibit Tumorigenesis

Citation: Cell Death and Disease (2013) 4, e759; doi:10.1038/cddis.2013.271 OPEN & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 2041-4889/13 www.nature.com/cddis Skp-cullin-F box E3 ligase component FBXL2 ubiquitinates Aurora B to inhibit tumorigenesis BB Chen*,1,2, JR Glasser1, TA Coon1 and RK Mallampalli*,1,3,4 Aurora B kinase is an integral regulator of cytokinesis, as it stabilizes the intercellular canal within the midbody to ensure proper chromosomal segregation during cell division. Here we identified that the ubiquitin E3 ligase complex SCFFBXL2 mediates Aurora B ubiquitination and degradation within the midbody, which is sufficient to induce mitotic arrest and apoptosis. Three molecular acceptor sites (K102,K103 and K207) within Aurora B protein were identified as important sites for its ubiquitination. A triple Lys mutant of Aurora B (K102/103/207R) exhibited optimal resistance to SCFFBXL2-directed polyubiquitination, and overexpression of this variant resulted in a significant delay in anaphase onset, resulting in apoptosis. A unique small molecule F-box/LRR-repeat protein 2 (FBXL2) activator, BC-1258, stabilized and increased levels of FBXL2 protein that promoted Aurora B degradation, resulting in tetraploidy, mitotic arrest and apoptosis of tumorigenic cells, and profoundly inhibiting tumor formation in athymic nude mice. These findings uncover a new proteolytic mechanism targeting a key regulator of cell replication that may serve as a basis for chemotherapeutic intervention in neoplasia. Cell Death and Disease (2013) 4, e759; doi:10.1038/cddis.2013.271; published online 8 August 2013 Subject Category: Cancer Normally, mammalian cells deploy numerous checkpoint and Cdc20, or assembly of an E3 ligase complex comprising enzymes that ensure faithful cell cycle progression and Cullin3 with the Bric-a-brac–Tramtrack–Broad complex Kelch mitosis. -

Dual Role of the PTPN13 Tyrosine Phosphatase in Cancer Soha Mcheik, Leticia Aptecar, Peter Coopman, Véronique D’Hondt, Gilles Freiss

Dual Role of the PTPN13 Tyrosine Phosphatase in Cancer Soha Mcheik, Leticia Aptecar, Peter Coopman, Véronique D’hondt, Gilles Freiss To cite this version: Soha Mcheik, Leticia Aptecar, Peter Coopman, Véronique D’hondt, Gilles Freiss. Dual Role of the PTPN13 Tyrosine Phosphatase in Cancer. Biomolecules, MDPI, 2020, 10, 10.3390/biom10121659. hal-03116270 HAL Id: hal-03116270 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03116270 Submitted on 20 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. biomolecules Review Dual Role of the PTPN13 Tyrosine Phosphatase in Cancer 1, 1, , 1,2 1 Soha Mcheik y, Leticia Aptecar y z, Peter Coopman ,Véronique D’Hondt and Gilles Freiss 1,* 1 IRCM, Institut de Recherche en Cancérologie de Montpellier, INSERM U1194, Université de Montpellier, F-34298 Montpellier, France; [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (L.A.); [email protected] (P.C.); [email protected] (V.D.) 2 CNRS—Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1919 Route de Mende, 34293 Montpellier, France * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-(0)4-67-61-24-33 These authors contributed equally to this work. -

Skp-Cullin-F Box E3 Ligase Component FBXL2 Ubiquitinates Aurora B to Inhibit Tumorigenesis

Citation: Cell Death and Disease (2013) 4, e759; doi:10.1038/cddis.2013.271 OPEN & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 2041-4889/13 www.nature.com/cddis Skp-cullin-F box E3 ligase component FBXL2 ubiquitinates Aurora B to inhibit tumorigenesis BB Chen*,1,2, JR Glasser1, TA Coon1 and RK Mallampalli*,1,3,4 Aurora B kinase is an integral regulator of cytokinesis, as it stabilizes the intercellular canal within the midbody to ensure proper chromosomal segregation during cell division. Here we identified that the ubiquitin E3 ligase complex SCFFBXL2 mediates Aurora B ubiquitination and degradation within the midbody, which is sufficient to induce mitotic arrest and apoptosis. Three molecular acceptor sites (K102,K103 and K207) within Aurora B protein were identified as important sites for its ubiquitination. A triple Lys mutant of Aurora B (K102/103/207R) exhibited optimal resistance to SCFFBXL2-directed polyubiquitination, and overexpression of this variant resulted in a significant delay in anaphase onset, resulting in apoptosis. A unique small molecule F-box/LRR-repeat protein 2 (FBXL2) activator, BC-1258, stabilized and increased levels of FBXL2 protein that promoted Aurora B degradation, resulting in tetraploidy, mitotic arrest and apoptosis of tumorigenic cells, and profoundly inhibiting tumor formation in athymic nude mice. These findings uncover a new proteolytic mechanism targeting a key regulator of cell replication that may serve as a basis for chemotherapeutic intervention in neoplasia. Cell Death and Disease (2013) 4, e759; doi:10.1038/cddis.2013.271; published online 8 August 2013 Subject Category: Cancer Normally, mammalian cells deploy numerous checkpoint and Cdc20, or assembly of an E3 ligase complex comprising enzymes that ensure faithful cell cycle progression and Cullin3 with the Bric-a-brac–Tramtrack–Broad complex Kelch mitosis. -

Table S1. 103 Ferroptosis-Related Genes Retrieved from the Genecards

Table S1. 103 ferroptosis-related genes retrieved from the GeneCards. Gene Symbol Description Category GPX4 Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Protein Coding AIFM2 Apoptosis Inducing Factor Mitochondria Associated 2 Protein Coding TP53 Tumor Protein P53 Protein Coding ACSL4 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 4 Protein Coding SLC7A11 Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 Protein Coding VDAC2 Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 2 Protein Coding VDAC3 Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 3 Protein Coding ATG5 Autophagy Related 5 Protein Coding ATG7 Autophagy Related 7 Protein Coding NCOA4 Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 4 Protein Coding HMOX1 Heme Oxygenase 1 Protein Coding SLC3A2 Solute Carrier Family 3 Member 2 Protein Coding ALOX15 Arachidonate 15-Lipoxygenase Protein Coding BECN1 Beclin 1 Protein Coding PRKAA1 Protein Kinase AMP-Activated Catalytic Subunit Alpha 1 Protein Coding SAT1 Spermidine/Spermine N1-Acetyltransferase 1 Protein Coding NF2 Neurofibromin 2 Protein Coding YAP1 Yes1 Associated Transcriptional Regulator Protein Coding FTH1 Ferritin Heavy Chain 1 Protein Coding TF Transferrin Protein Coding TFRC Transferrin Receptor Protein Coding FTL Ferritin Light Chain Protein Coding CYBB Cytochrome B-245 Beta Chain Protein Coding GSS Glutathione Synthetase Protein Coding CP Ceruloplasmin Protein Coding PRNP Prion Protein Protein Coding SLC11A2 Solute Carrier Family 11 Member 2 Protein Coding SLC40A1 Solute Carrier Family 40 Member 1 Protein Coding STEAP3 STEAP3 Metalloreductase Protein Coding ACSL1 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 1 Protein -

Universidad Autónoma De Madrid

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Departamento de Bioquímica Identification of the substrates of the protease MT1-MMP in TNFα- stimulated endothelial cells by quantitative proteomics. Analysis of their potential use as biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease. Agnieszka A. Koziol Tesis doctoral Madrid, 2013 2 Departamento de Bioquímica Facultad de Medicina Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Identification of the substrates of the protease MT1-MMP in TNFα- stimulated endothelial cells by quantitative proteomics. Analysis of their potential use as biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease. Memoria presentada por Agnieszka A. Koziol licenciada en Ciencias Biológicas para optar al grado de Doctor. Directora: Dra Alicia García Arroyo Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) Madrid, 2013 3 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS - ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS - First and foremost I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Alicia García Arroyo for giving me the great opportunity to study under her direction. Her encouragement, guidance and support from the beginning to the end, enabled me to develop and understand the subject. Her feedback to this manuscript, critical reading and corrections was inappreciable to finish this dissertation. Next, I would like to express my gratitude to those who helped me substantially along the way. To all members of MMPs’ lab, for their interest in the project, teaching me during al these years and valuable contribution at the seminary discussion. Without your help it would have not been possible to do some of those experiments. Thank you all for creating a nice atmosphere at work and for being so good friends in private. I would like to also thank all of the collaborators and technical units for their support and professionalism. -

Statistical Methods to Infer Biological Interactions George Jay Tucker

Statistical methods to infer biological interactions by George Jay Tucker B.S., Harvey Mudd College (2008) Submitted to the Department of Mathematics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Mathematics at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2014 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2014. All rights reserved. Author.............................................................. Department of Mathematics May 1, 2014 Certified by. Bonnie Berger Professor of Applied Mathematics Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . Michel X. Goemans Chairman, Applied Mathematics Committee 2 Statistical methods to infer biological interactions by George Jay Tucker Submitted to the Department of Mathematics on May 1, 2014, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Mathematics Abstract Biological systems are extremely complex, and our ability to experimentally measure interactions in these systems is limited by inherent noise. Technological advances have allowed us to collect unprecedented amounts of raw data, increasing the need for computational methods to disentangle true interactions from noise. In this thesis, we focus on statistical methods to infer two classes of important biological interactions: protein-protein interactions and the link between genotypes and phenotypes. In the first part of the thesis, we introduce methods to infer protein-protein interactions from affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) and from luminescence-based mam- malian interactome mapping (LUMIER). Our work reveals novel context dependent interactions in the MAPK signaling pathway and insights into the protein homeostasis machinery. In the second part, we focus on methods to understand the link between genotypes and phenotypes. First, we characterize the effects of related individuals on standard association statistics for genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and introduce a new statistic that corrects for relatedness. -

Fbxw11 Promotes the Proliferation of Lymphocytic Leukemia Cells

Wang et al. Cell Death and Disease (2018) 9:427 DOI 10.1038/s41419-018-0440-1 Cell Death & Disease ARTICLE Open Access Fbxw11 promotes the proliferation of lymphocytic leukemia cells through the concomitant activation of NF-κBandβ- catenin/TCF signaling pathways Lina Wang1,WenliFeng1,XiaoYang1,FeifeiYang1, Rong Wang1,QianRen1, Xiaofan Zhu1 andGuoguangZheng 1 Abstract The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) participates in both physiological and pathological processes through the posttranslational regulation of intracellular signal transduction pathways. F-box and WD-40 domain protein 11 (Fbxw11) is a component of the SCF (Skp1–Cul1–F-box) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Fbxw11 regulates various signal transduction pathways, and it may have pathological roles in tumorigenesis. However, the role of Fbxw11 in the development of leukemia and the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. In this study, Fbxw11 expression was aberrantly upregulated in patients with lymphocytic leukemia. Its expression was dramatically decreased in patients who achieved complete remission (CR) after chemotherapy. The high level of Fbxw11 expression in L1210 lymphocytic leukemia cells stimulated cell proliferation in vitro and tumor formation in vivo. The effects were mediated by the stimulation of cell cycle progression rather than the induction of apoptosis. Furthermore, a bioinformatics analysis suggested concomitant activation of the NF-κB and β-catenin/TCF signaling pathways, which fi 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; were con rmed by reporter gene assays. Moreover, blocking experiments suggested the involvement of both pathways in the growth-promoting effects of Fbxw11. Our results reveal the role of Fbxw11 in lymphocytic leukemia cells and imply that Fbxw11 may serve as a potential molecular target for the treatment of lymphocytic leukemia. -

A Structurally-Validated Multiple Sequence Alignment of 497 Human

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/776740; this version posted November 4, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. A Structurally-Validated Multiple Sequence Alignment of 497 Human Protein Kinase Domains Vivek Modi Roland L. Dunbrack, Jr.* Fox Chase Cancer Center 333 Cottman Avenue Philadelphia PA 19111 * Correspondence: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/776740; this version posted November 4, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Abstract Studies on the structures and functions of individual kinases have been used to understand the biological properties of other kinases that do not yet have experimental structures. The key factor in accurate inference by homology is an accurate sequence alignment. We present a parsimonious, structure-based multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of 497 human protein kinase domains excluding atypical kinases, even those with related but somewhat different folds. The alignment is arranged in 17 blocks of conserved regions and unaligned blocks in between that contain insertions of varying lengths present in only a subset of kinases. The aligned blocks contain well-conserved elements of secondary structure and well-known functional motifs, such as the DFG and HRD motifs. -

The Potential Role of Selected Mirna in Uveal Melanoma Primary Tumors As Early Biomarkers of Disease Progression

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article The Potential Role of Selected miRNA in Uveal Melanoma Primary Tumors as Early Biomarkers of Disease Progression Joanna Patrycja Wróblewska 1,2,* , Michał Stefan Lach 3,4 , Adam Ustaszewski 5, Katarzyna Kulcenty 3,4 , Matthew Ibbs 1,2 , Inga Jagiełło 2, Wiktoria Maria Suchorska 3,4 and Andrzej Marszałek 1,2 1 Department of Oncologic Pathology and Prophylaxis, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Garbary 15, 61-866 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (A.M.) 2 Department of Tumor Pathology, Greater Poland Cancer Centre, Garbary 15, 61-866 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] 3 Radiobiology Lab, Department of Medical Physics, Greater Poland Cancer, Garbary 15, 61-866 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] (M.S.L.); [email protected] (K.K.); [email protected] (W.M.S.) 4 Department of Electroradiology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Garbary 15, 61-866 Poznan, Poland 5 Institute of Human Genetics, Polish Academy of Sciences, Strzeszynska 32, 60-479 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 31 January 2020; Accepted: 27 February 2020; Published: 2 March 2020 Abstract: Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary tumor of the eye diagnosed in adults, associated with a high risk of metastasis and thereby, poor prognosis. Among known risk factors for the development of metastatic disease is the loss of BAP1 expression and chromosome 3 monosomy in the primary tumor. However, the expression levels of specific micro RNAs (miRNA) in tumor tissue may also serve as a valuable marker for determining the risk of metastatic disease in patients with primary uveal melanoma. -

Genes That Are Preferentially Expressed in Type I Cells Figure 4A

Genes that are preferentially expressed in Type I cells Figure 4A Rank Moltid 3'ACC Gene Title #Cell_lines Variance PCC 1 GC17295 AA055114 PIK3R1 phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit, polypeptide 1 (p85 alpha) 22 0.023 0.774 2 GC15242 N89600 Homo sapiens cDNA: FLJ22300 fis, clone HRC04759.similar to Rabbit smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase22 0.356 0.773 3 GC17179 AA041360 RIG regulated in glioma, DKK-3 (xenopus dick kopf ortholog) 22 0.086 0.766 4 GC16514 W92322 ITGA5 integrin, alpha 5 (fibronectin receptor, alpha polypeptide) 22 0.04 0.761 5 GC11221 H16240 EST 22 0.049 0.761 6 GC17336 AA056228 ZDHHC7 zinc finger, DHHC domain containing 7 22 0.047 0.759 7 GC9826 AA047403 TPM1 tropomyosin 1 (alpha) 22 0.207 0.74 8 GC16967 AA025392 DUSP3 dual specificity phosphatase 3 (vaccinia virus phosphatase VH1-related) 22 0.046 0.739 9 GC12698 H24785 ESTs 20 0.136 0.735 10 GC12641 R54846 FGFR1 fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (fms-related tyrosine kinase 2, Pfeiffer syndrome) 22 0.178 0.734 11 GC18963 AA040161 SNK serum-inducible kinase 22 0.319 0.732 12 GC15075 N73979 SCHIP1 schwannomin interacting protein 1 22 0.117 0.732 13 GC17213 AA046749 TPM1 tropomyosin 1 (alpha) 22 0.179 0.723 14 GC14991 N71362 TRIM3 tripartite motif-containing 3 22 0.115 0.72 15 GC14893 N72246 NIT2 Nit protein 2 22 0.029 0.719 16 GC14878 N71998 ITGA3 integrin, alpha 3 (antigen CD49C, alpha 3 subunit of VLA-3 receptor) 22 0.226 0.719 17 GC11743 T50788 UGT2B15 UDP glycosyltransferase 2 family, polypeptide B15 20 0.347 0.713 18 GC18514 AA031453 KIAA0638 KIAA0638 -

Ubiquitin-Mediated Degradation of Aurora Kinases

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo REVIEW published: 18 January 2016 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00307 Ubiquitin-Mediated Degradation of Aurora Kinases Catherine Lindon1* , Rhys Grant1 and Mingwei Min2 1 Department of Pharmacology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2 Department of Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA The Aurora kinases are essential regulators of mitosis in eukaryotes. In somatic cell divisions of higher eukaryotes, the paralogs Aurora kinase A (AurA) and Aurora kinase B (AurB) play non-overlapping roles that depend on their distinct spatiotemporal activ- ities. These mitotic roles of Aurora kinases depend on their interactions with different partners that direct them to different mitotic destinations and different substrates: AurB is a component of the chromosome passenger complex that orchestrates the tasks of chromosome segregation and cytokinesis, while AurA has many known binding partners and mitotic roles, including a well-characterized interaction with TPX2 that mediates its role in mitotic spindle assembly. Beyond the spatial control conferred by different binding partners, Aurora kinases are subject to temporal control of their activation and inactivation. Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis is a critical route to irreversible inactivation of these kinases, which must occur for ordered transition from mitosis back to interphase. Edited by: Both AurA and AurB undergo targeted proteolysis after anaphase onset as substrates Claude Prigent, of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) ubiquitin ligase, even while CNRS, France they continue to regulate steps during mitotic exit. Temporal control of Aurora kinase Reviewed by: Raquel Aloyz, destruction ensures that AurB remains active at the midbody during cytokinesis long after Lady Davis Institute for Medical AurA activity has been largely eliminated from the cell.