Investigating the Potential Magnetic Origin of Wind Variability in OB Stars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apparent and Absolute Magnitudes of Stars: a Simple Formula

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 96 (2018) 120-133 EISSN 2392-2192 Apparent and Absolute Magnitudes of Stars: A Simple Formula Dulli Chandra Agrawal Department of Farm Engineering, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi - 221005, India E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT An empirical formula for estimating the apparent and absolute magnitudes of stars in terms of the parameters radius, distance and temperature is proposed for the first time for the benefit of the students. This reproduces successfully not only the magnitudes of solo stars having spherical shape and uniform photosphere temperature but the corresponding Hertzsprung-Russell plot demonstrates the main sequence, giants, super-giants and white dwarf classification also. Keywords: Stars, apparent magnitude, absolute magnitude, empirical formula, Hertzsprung-Russell diagram 1. INTRODUCTION The visible brightness of a star is expressed in terms of its apparent magnitude [1] as well as absolute magnitude [2]; the absolute magnitude is in fact the apparent magnitude while it is observed from a distance of . The apparent magnitude of a celestial object having flux in the visible band is expressed as [1, 3, 4] ( ) (1) ( Received 14 March 2018; Accepted 31 March 2018; Date of Publication 01 April 2018 ) World Scientific News 96 (2018) 120-133 Here is the reference luminous flux per unit area in the same band such as that of star Vega having apparent magnitude almost zero. Here the flux is the magnitude of starlight the Earth intercepts in a direction normal to the incidence over an area of one square meter. The condition that the Earth intercepts in the direction normal to the incidence is normally fulfilled for stars which are far away from the Earth. -

Today Our Place in the Universe

Our place in the Universe , and other sources ully T , Bob Patterson, Donna Cox (NCSA), Data: Hipparcos, Brent iz: Stuart Levy V Tom Abel Today KIPAC The Birth, Life & Aftermath of the First Stars Tom Abel KIPAC/Stanford work with Matt Turk (Birth) John Wise (Life) Ralf Kähler (Scientific Visualization) Outline • Conception • A difficult birth • A surprising life • Remarkable consequences • Three-D radiation transport around point sources • Spatially & temporally structured adaptive cosmological & relativistic hydrodynamics • public version of enzo at: http://lca.ucsd.edu/portal/software/enzo Discovery by How we find things: Computer? 6 6.28 Conception Physics problem: • Initial Conditions: COBE/ACBAR/ Boomerang/WMAP/CfA/SDDS/ 2DF/CDMS/DAMA/Edelweiss/... + Theory: Constituents, Density Fluctuations, Thermal History • Physics: Gravity, MHD, Chemistry, Radiative Cooling, Radiation Transport, Cosmic Rays, Dust drift & cooling, Supernovae, Stellar evolution, etc. Ralf Kähler & Tom Abel for PBS • Transition from Linear to Non- Origins. Aired Dec 04 Linear: • Using patched based structured adaptive (space & time) mesh refinement Making a proto-star Simulation: Tom Abel (KIPAC/Stanford), Greg Bryan (Columbia), Mike Norman (UCSD) Viz: Ralf Kähler (AEI, ZIB, KIPAC), Bob Patterson, Stuart Levy, Donna Cox (NCSA), Tom Abel © “The Unfolding Universe” Discovery Channel 2002 Dynamic range ~1e12. Typically 3 solar mass dm particles > 30 levels of refinement > 8 cells per local Jeans Length tens of thousands of grid patches non-equilibrium chemistry dynamically load balanced RT effects above 1e12 cm-3 Zoom in MPI. 16 processors enough Turk & Abel in prep Note disks within disks happen routinely in turbulent collapses! Mass Scales? Kelvin Helmholtz time at ZAMS Abel, Bryan & Norman 2002 Recap First Stars are isolated and very massive • Theoretical uncertainty: 30 - 300 solar mass Many simulations with three different numerical techniques and a large range of numerical resolutions have converged to this result. -

Astronomy Magazine Special Issue

γ ι ζ γ δ α κ β κ ε γ β ρ ε ζ υ α φ ψ ω χ α π χ φ γ ω ο ι δ κ α ξ υ λ τ μ β α σ θ ε β σ δ γ ψ λ ω σ η ν θ Aι must-have for all stargazers η δ μ NEW EDITION! ζ λ β ε η κ NGC 6664 NGC 6539 ε τ μ NGC 6712 α υ δ ζ M26 ν NGC 6649 ψ Struve 2325 ζ ξ ATLAS χ α NGC 6604 ξ ο ν ν SCUTUM M16 of the γ SERP β NGC 6605 γ V450 ξ η υ η NGC 6645 M17 φ θ M18 ζ ρ ρ1 π Barnard 92 ο χ σ M25 M24 STARS M23 ν β κ All-in-one introduction ALL NEW MAPS WITH: to the night sky 42,000 more stars (87,000 plotted down to magnitude 8.5) AND 150+ more deep-sky objects (more than 1,200 total) The Eagle Nebula (M16) combines a dark nebula and a star cluster. In 100+ this intense region of star formation, “pillars” form at the boundaries spectacular between hot and cold gas. You’ll find this object on Map 14, a celestial portion of which lies above. photos PLUS: How to observe star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies AS2-CV0610.indd 1 6/10/10 4:17 PM NEW EDITION! AtlAs Tour the night sky of the The staff of Astronomy magazine decided to This atlas presents produce its first star atlas in 2006. -

Galactic Extinction Laws: II. Hidden in Plain Sight, a New Interstellar Absorption Band at 7700 Å Broader Than Any Known DIB

MNRAS 000,1–17 (2020) Preprint 4 August 2020 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Galactic extinction laws: II. Hidden in plain sight, a new interstellar absorption band at 7700 Å broader than any known DIB J. Maíz Apellániz,1? R. H. Barbá,2 J. A. Caballero,1 R. C. Bohlin3; and C. Fariña4;5 1Centro de Astrobiología. CSIC-INTA. Campus ESAC. Camino bajo del castillo s/n. E-28 692 Villanueva de la Cañada. Madrid. Spain. 2Departamento de Astronomía. Universidad de La Serena. Av. Cisternas 1200 Norte. La Serena. Chile. 3Space Telescope Science Institute. 3700 San Martin Drive. Baltimore, MD 21 218, U.S.A. 4Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias. E-38 200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain. 5Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes. Apartado de correos 321. E-38 700 Santa Cruz de La Palma, La Palma, Spain. Accepted 2020 August 3. Received 2020 August 3; in original form 2020 June 4. ABSTRACT We have detected a broad interstellar absorption band centred close to 7700 Å and with a FWHM of 176.6±3.9 Å. This is the first such absorption band detected in the optical range and is significantly wider than the numerous diffuse interstellar bands (DIBs). It remained undiscovered until now because it is partially hidden behind the A telluric band produced by O2. The band was discovered using STIS@HST spectra and later detected in a large sample of stars of diverse type (OB stars, BA supergiants, red giants) using further STIS and ground- based spectroscopy. The EW of the band is measured and compared with our extinction and K i λλ7667.021,7701.093 measurements for the same sample. -

October, 2011

IN THIS ISSUE: OCTOBER 2011 Event Calendar, News Notes Minutes of the September Meeting MVAS Reminders: Party-on MVAS Activities: On The Road Again Observer’s Notes: Variable Heroines MVAS Homework: M-76, Little Dumbbell Homework Charts: Algol, asteroid (15) Eunomia Constellation of the Month: Perseus November 2011 Sky Almanac Gallery: Comet Quest, Summer Photos Meteorite Editor: Phil Plante 1982 Mathews Rd. #2 Youngstown OH 44514 OCTOBER 2011 NEWS NOTES Newsletter of the Mahoning Valley Astronomical Society, Inc. The Big Ear. Lofar (Low Frequency Array) is a new kind of radio telescope. It can see radio waves with low frequencies, similar to those that give us FM radio. Rather than collecting MVAS CALENDAR signals from individual radio sources, Lofar continuously monitors large swathes of sky. Lofar is more sensitive to the OCT 22 Business meeting at the MVCO 8:00 PM longest observable radio waves than any other telescope. It can OCT 29 Halloween Party at the MVCO 7:00 PM see many billions of light years out into space, back to the time before the first stars formed, a few hundred million years after NOV17/18 Leonid Meteor watch. On your own? Midnight… the Big Bang. On Monday, September 21, 2011, Sweden's Minister for Education and Research, Jan Bjorklund, opened the NOV 19 Business meeting at YSU. Show at 8:00 PM Onsala Space Observatory's newest telescope; to become part NOV 26 Star Party at the MVCO. 7:00 PM till…. of Lofar, which is the world's largest radio telescope. The 192 new radio antennas at Onsala's Lofar station will be linked together with 47 similar stations over the whole of NATIONAL & REGIONAL EVENTS Europe, and sent over the Internet to a central supercomputer in OCT 24 - 30 CSPG Fall Star Party, held in Chiefland, FL . -

Volume 75 Nos 3 & 4 April 2016 News Note

Volume 75 Nos 3 & 4 April 2016 In this issue: News Note – Galaxy alignment on a cosmic scale News Note – Presentation of EdinburghMedal Port Elizabeth Peoples’ Observatory Updated Biographical Index to MNASSA and JASSA EDITORIAL Mr Case Rijsdijk (Editor, MNASSA ) BOARD Mr Auke Slotegraaf (Editor, Sky Guide Africa South ) Mr Christian Hettlage (Webmaster) Prof M.W. Feast (Member, University of Cape Town) Prof B. Warner (Member, University of Cape Town) MNASSA Mr Case Rijsdijk (Editor, MNASSA ) PRODUCTION Dr Ian Glass (Assistant Editor) Ms Lia Labuschagne (Book Review Editor) Willie Koorts (Consultant) EDITORIAL MNASSA, PO Box 9, Observatory 7935, South Africa ADDRESSES Email: [email protected] Web page: http://mnassa.saao.ac.za MNASSA Download Page: www.mnassa.org.za SUBSCRIPTIONS MNASSA is available for free download on the Internet ADVERTISING Advertisements may be placed in MNASSA at the following rates per insertion: full page R400, half page R200, quarter page R100. Small advertisements R2 per word. Enquiries should be sent to the editor at [email protected] CONTRIBUTIONS MNASSA mainly serves the Southern African astronomical community. Articles may be submitted by members of this community or by those with strong connections. Else they should deal with matters of direct interest to the community . MNASSA is published on the first day of every second month and articles are due one month before the publication date. RECOGNITION Articles from MNASSA appear in the NASA/ADS data system. Cover picture: An image of the deep radio map covering the ELAIS-N1 region, with aligned galaxy jets. The image on the left has white circles around the aligned galaxies; the image on the right is without the circles. -

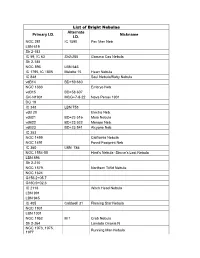

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Patrick Moore's Practical Astronomy Series

Patrick Moore’s Practical Astronomy Series Other Titles in this Series Telescopes and Techniques (2nd Edn.) Observing the Planets Chris Kitchin Peter T. Wlasuk The Art and Science of CCD Astronomy Light Pollution David Ratledge (Ed.) Bob Mizon The Observer’s Year Using the Meade ETX Patrick Moore Mike Weasner Seeing Stars Practical Amateur Spectroscopy Chris Kitchin and Robert W. Forrest Stephen F. Tonkin (Ed.) Photo-guide to the Constellations More Small Astronomical Observatories Chris Kitchin Patrick Moore (Ed.) The Sun in Eclipse Observer’s Guide to Stellar Evolution Michael Maunder and Patrick Moore Mike Inglis Software and Data for Practical Astronomers How to Observe the Sun Safely David Ratledge Lee Macdonald Amateur Telescope Making The Practical Astronomer’s Deep-Sky Stephen F. Tonkin (Ed.) Companion Observing Meteors, Comets, Supernovae and Jess K. Gilmour other Transient Phenomena Observing Comets Neil Bone Nick James and Gerald North Astronomical Equipment for Amateurs Observing Variable Stars Martin Mobberley Gerry A. Good Transit: When Planets Cross the Sun Visual Astronomy in the Suburbs Michael Maunder and Patrick Moore Antony Cooke Practical Astrophotography Astronomy of the Milky Way: The Observer’s Jeffrey R. Charles Guide to the Northern and Southern Milky Way Observing the Moon (2 volumes) Peter T. Wlasuk Mike Inglis Deep-Sky Observing The NexStar User Guide Steven R. Coe Michael W. Swanson AstroFAQs Observing Binary and Double Stars Stephen F. Tonkin Bob Argyle (Ed.) The Deep-Sky Observer’s Year Navigating the Night Sky Grant Privett and Paul Parsons Guilherme de Almeida Field Guide to the Deep Sky Objects The New Amateur Astronomer Mike Inglis Martin Mobberley Choosing and Using a Schmidt-Cassegrain Care of Astronomical Telescopes and Telescope Accessories Rod Mollise M. -

Stars and Their Spectra: an Introduction to the Spectral Sequence Second Edition James B

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89954-3 - Stars and Their Spectra: An Introduction to the Spectral Sequence Second Edition James B. Kaler Index More information Star index Stars are arranged by the Latin genitive of their constellation of residence, with other star names interspersed alphabetically. Within a constellation, Bayer Greek letters are given first, followed by Roman letters, Flamsteed numbers, variable stars arranged in traditional order (see Section 1.11), and then other names that take on genitive form. Stellar spectra are indicated by an asterisk. The best-known proper names have priority over their Greek-letter names. Spectra of the Sun and of nebulae are included as well. Abell 21 nucleus, see a Aurigae, see Capella Abell 78 nucleus, 327* ε Aurigae, 178, 186 Achernar, 9, 243, 264, 274 z Aurigae, 177, 186 Acrux, see Alpha Crucis Z Aurigae, 186, 269* Adhara, see Epsilon Canis Majoris AB Aurigae, 255 Albireo, 26 Alcor, 26, 177, 241, 243, 272* Barnard’s Star, 129–130, 131 Aldebaran, 9, 27, 80*, 163, 165 Betelgeuse, 2, 9, 16, 18, 20, 73, 74*, 79, Algol, 20, 26, 176–177, 271*, 333, 366 80*, 88, 104–105, 106*, 110*, 113, Altair, 9, 236, 241, 250 115, 118, 122, 187, 216, 264 a Andromedae, 273, 273* image of, 114 b Andromedae, 164 BDþ284211, 285* g Andromedae, 26 Bl 253* u Andromedae A, 218* a Boo¨tis, see Arcturus u Andromedae B, 109* g Boo¨tis, 243 Z Andromedae, 337 Z Boo¨tis, 185 Antares, 10, 73, 104–105, 113, 115, 118, l Boo¨tis, 254, 280, 314 122, 174* s Boo¨tis, 218* 53 Aquarii A, 195 53 Aquarii B, 195 T Camelopardalis, -

GTO Keypad Manual, V5.001

ASTRO-PHYSICS GTO KEYPAD Version v5.xxx Please read the manual even if you are familiar with previous keypad versions Flash RAM Updates Keypad Java updates can be accomplished through the Internet. Check our web site www.astro-physics.com/software-updates/ November 11, 2020 ASTRO-PHYSICS KEYPAD MANUAL FOR MACH2GTO Version 5.xxx November 11, 2020 ABOUT THIS MANUAL 4 REQUIREMENTS 5 What Mount Control Box Do I Need? 5 Can I Upgrade My Present Keypad? 5 GTO KEYPAD 6 Layout and Buttons of the Keypad 6 Vacuum Fluorescent Display 6 N-S-E-W Directional Buttons 6 STOP Button 6 <PREV and NEXT> Buttons 7 Number Buttons 7 GOTO Button 7 ± Button 7 MENU / ESC Button 7 RECAL and NEXT> Buttons Pressed Simultaneously 7 ENT Button 7 Retractable Hanger 7 Keypad Protector 8 Keypad Care and Warranty 8 Warranty 8 Keypad Battery for 512K Memory Boards 8 Cleaning Red Keypad Display 8 Temperature Ratings 8 Environmental Recommendation 8 GETTING STARTED – DO THIS AT HOME, IF POSSIBLE 9 Set Up your Mount and Cable Connections 9 Gather Basic Information 9 Enter Your Location, Time and Date 9 Set Up Your Mount in the Field 10 Polar Alignment 10 Mach2GTO Daytime Alignment Routine 10 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR NEW SETUPS OR SETUP IN NEW LOCATION 11 Assemble Your Mount 11 Startup Sequence 11 Location 11 Select Existing Location 11 Set Up New Location 11 Date and Time 12 Additional Information 12 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR MOUNTS USED AT THE SAME LOCATION WITHOUT A COMPUTER 13 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR COMPUTER CONTROLLED MOUNTS 14 1 OBJECTS MENU – HAVE SOME FUN! -

Atlas Menor Was Objects to Slowly Change Over Time

C h a r t Atlas Charts s O b by j Objects e c t Constellation s Objects by Number 64 Objects by Type 71 Objects by Name 76 Messier Objects 78 Caldwell Objects 81 Orion & Stars by Name 84 Lepus, circa , Brightest Stars 86 1720 , Closest Stars 87 Mythology 88 Bimonthly Sky Charts 92 Meteor Showers 105 Sun, Moon and Planets 106 Observing Considerations 113 Expanded Glossary 115 Th e 88 Constellations, plus 126 Chart Reference BACK PAGE Introduction he night sky was charted by western civilization a few thou - N 1,370 deep sky objects and 360 double stars (two stars—one sands years ago to bring order to the random splatter of stars, often orbits the other) plotted with observing information for T and in the hopes, as a piece of the puzzle, to help “understand” every object. the forces of nature. The stars and their constellations were imbued with N Inclusion of many “famous” celestial objects, even though the beliefs of those times, which have become mythology. they are beyond the reach of a 6 to 8-inch diameter telescope. The oldest known celestial atlas is in the book, Almagest , by N Expanded glossary to define and/or explain terms and Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian with Roman citizenship who lived concepts. in Alexandria from 90 to 160 AD. The Almagest is the earliest surviving astronomical treatise—a 600-page tome. The star charts are in tabular N Black stars on a white background, a preferred format for star form, by constellation, and the locations of the stars are described by charts. -

MONTHLY OBSERVER's CHALLENGE Las Vegas

MONTHLY OBSERVER’S CHALLENGE Las Vegas Astronomical Society Compiled by: Roger Ivester, Boiling Springs, North Carolina & Fred Rayworth, Las Vegas, Nevada With special assistance from: Rob Lambert, Alabama JANUARY 2018 NGC-1624/SH2-212 Cluster/Nebula In Perseus “Sharing Observations and Bringing Amateur Astronomers Together” Introduction The purpose of the Observer’s Challenge is to encourage the pursuit of visual observing. It’s open to everyone that’s interested, and if you’re able to contribute notes, and/or drawings, we’ll be happy to include them in our monthly summary. We also accept digital imaging. Visual astronomy depends on what’s seen through the eyepiece. Not only does it satisfy an innate curiosity, but it allows the visual observer to discover the beauty and the wonderment of the night sky. Before photography, all observations depended on what the astronomer saw in the eyepiece, and how they recorded their observations. This was done through notes and drawings, and that’s the tradition we’re stressing in the Observers Challenge. We’re not excluding those with an interest in astrophotography, either. Your images and notes are just as welcome. The hope is that you’ll read through these reports and become inspired to take more time at the eyepiece, study each object, and look for those subtle details that you might never have noticed before. NGC-1624/SH2-212 Cluster/Nebula In Perseus NGC-1624, also known as Collinder 53, is an open cluster located inside an emission nebula, SH2-212, located in the constellation of Perseus. It was discovered by William Herschel in 1790, yet strangely enough, it never made his list of 2,500 objects or obtained a Herschel numbered designation.