Polly Schaafsma: Imagery and Anthropolgy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ALTERNATE PATHWAYS TO RITUAL POWER: EVIDENCE FOR CENTRALIZED PRODUCTION AND LONG-DISTANCE EXCHANGE BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CADDO COMMUNITIES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By SHAWN PATRICK LAMBERT Norman, Oklahoma 2017 ALTERNATE PATHWAYS TO RITUAL POWER: EVIDENCE FOR CENTRALIZED PRODUCTION AND LONG-DISTANCE EXCHANGE BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CADDO COMMUNITIES A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Patrick Livingood, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Asa Randall ______________________________ Dr. Amanda Regnier ______________________________ Dr. Scott Hammerstedt ______________________________ Dr. Diane Warren ______________________________ Dr. Bonnie Pitblado ______________________________ Dr. Michael Winston © Copyright by SHAWN PATRICK LAMBERT 2017 All Rights Reserved. Dedication I dedicate my dissertation to my loving grandfather, Calvin McInnish and wonderful twin sister, Kimberly Dawn Thackston. I miss and love you. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I want to give my sincerest gratitude to Patrick Livingood, my committee chair, who has guided me through seven years of my masters and doctoral work. I could not wish for a better committee chair. I also want to thank Amanda Regnier and Scott Hammerstedt for the tremendous amount of work they put into making me the best possible archaeologist. I would also like to thank Asa Randall. His level of theoretical insight is on another dimensional plane and his Advanced Archaeological Theory class is one of the best I ever took at the University of Oklahoma. I express appreciation to Bonnie Pitblado, not only for being on my committee but emphasizing the importance of stewardship in archaeology. -

Indiana Archaeology

INDIANA ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 5 Number 2 2010/2011 Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Indiana Department of Natural Resources Robert E. Carter, Jr., Director and State Historic Preservation Officer Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) James A. Glass, Ph.D., Director and Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer DHPA Archaeology Staff James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson Cathy L. Draeger-Williams Cathy A. Carson Wade T. Tharp Editors James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson, Senior Archaeologist and Archaeology Outreach Coordinator Cathy A. Carson, Records Check Coordinator Publication Layout: Amy L. Johnson Additional acknowledgments: The editors wish to thank the authors of the submitted articles, as well as all of those who participated in, and contributed to, the archaeological projects which are highlighted. Cover design: The images which are featured on the cover are from several of the individual articles included in this journal. Mission Statement: The Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology promotes the conservation of Indiana’s cultural resources through public education efforts, financial incentives including several grant and tax credit programs, and the administration of state and federally mandated legislation. 2 For further information contact: Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology 402 W. Washington Street, Room W274 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2739 Phone: 317/232-1646 Email: [email protected] www.IN.gov/dnr/historic 2010/2011 3 Indiana Archaeology Volume 5 Number 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Authors of articles were responsible for ensuring that proper permission for the use of any images in their articles was obtained. -

Program Wednesday Afternoon April 22, 2009 Wednesday Evening April

THURSDAY MORNING: April 23, 2009 23 Program Wednesday Afternoon April 22, 2009 [1A] Workshop NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN THE PRESERVATION OF DIGITAL DATA FOR ARCHAEOLOGY Room: L404 Time: 1:00 AM−4:30 PM Wednesday Evening April 22, 2009 [1] SYMPOSIUM ARCHAEOLOGY BEYOND ARCHAEOLOGY Room: Marquis Ballroom Time: 6:00 PM−9:00 PM Organizers: Michael Smith and Michael Barton Chairs: Michelle Hegmon and Michael Barton Participants: 6:00 Michael Smith—Just How Useful is Archaeology for Scientists and Scholars in Other Disciplines? 6:15 Tim Kohler—Model-Based Archaeology as a Foundation for Interdisciplinary and Comparative Research, and an Antidote to Agency/Practice Perspectives 6:30 Michael Barton—From Narratives to Algorithms: Extending Archaeological Explanation Beyond Archaeology 6:45 Margaret Nelson—Long-term vulnerability and resilience 7:00 Joseph Tainter—Energy Gain and Organization 7:15 Patrick Kirch—Archaeology and Biocomplexity 7:30 Rebecca Storey—Urban Health from Prehistoric times to a Highly Urbanized Contemporary World 7:45 Carla Sinopoli—Historicizing Prehistory: Archaeology and historical interpretation in Late Prehistoric Karnataka, India 8:00 Michelle Hegmon—Crossing Spatial-Temporal Scales, Expanding Social Theory 8:15 Robert Costanza—Sustainability or Collapse: What Can We Learn from Integrating the History of Humans and the Rest of Nature? 8:30 Robert Costanza—Discussant 8:45 James Brooks—Discussant Thursday Morning April 23, 2009 [2] GENERAL SESSION RECENT RESEARCH IN CENTRAL AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY Room: International C Time: 8:00 -

Issn 0882-4894 2013

ISSN 0882-4894 VOLUME 6 2013 Pictures Courtesy of authors John McGreevy, Rebecca Simon, and Ashley Packard ARCHAEOLOGY Changing Perspectives on Repatriation Christopher Green.......................................................................................................................................... 3 Use Wear Patterns on Metate Prior to and Immediately Following 20 Hours of Grinding Ashley Packard................................................................................................................................................. 12 Understanding the Variation of Rio Grande Ceramics Rebecca Simon................................................................................................................................................. 18 BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY Post-Mortem Care Warfare: Can Conflict between Mandated Autopsies and Cultural Expectations for Post-Mortem Body Care be Resolved? Joshua Clementz and Bonnie Glass-Coffin........................................................................................ 27 Born to be Wide: A Re-valuation of the Claim that Neandertal Skeletal Morphology Represents a Uniquely Derived Condition Chris Davis.......................................................................................................................................................... 37 CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY First-generation College Attendance: The Motivational Process Scarlett Eisenhauer........................................................................................................................................ -

Guide to the Department of Anthropology Records, 1840-Circa 2015

Guide to the Department of Anthropology records, 1840-circa 2015 James R. Glenn and Janet Kennelly August 2000 National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland, Maryland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative History...................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 5 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Correspondence, 1902-1908, 1961-1992................................................. 6 Series 2: Alpha-Subject File, 1828-1963................................................................ 35 Series 3: Alpha-Subject File, 1961-1975................................................................ 82 Series 4: Smithsonian Office of Anthropology Subject Files, 1967-1968............ -

1939-1940 Excavation Project at Quarai Pueblo and Mission Buildings Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, New Mexico

SOUTHWEST REGIONAL OFFICE OPOLOGY DIVISION OF HISTORY I 29.116:29 The 1939-1940 Excavation Pr. i..L- 1707-17^ EXCAVATION PROJECT AT QUARAI PUEBLO AND MISSION BUILDING Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, New Mexico PUP' IC DOCUMENTS Clemson University DF JiM ITEM 3 1604 019 699 729 OCT 2 3 1990 CLEIMISON «•»•• *« 4P&* ;^*5il WESLEY R. HURT National Park Service Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Paper No. 29 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/19391940excavati00hurt THE 1939-1940 EXCAVATION PROJECT AT QUARAI PUEBLO AND MISSION BUILDINGS SALINAS PUEBLO MISSIONS NATIONAL MONUMENT, NEW MEXICO PUBLIC DOCUMENTS DEPOSITORY ITEM OCT 2 3 1990 CLEMSON Wesley R. Hurt LIBRARY. 1990 Division of History Division of Anthropology National Park Service Santa Fe, New Mexico Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers Number 29 PUBLISHED REPORTS OF THE SOUTHWEST CULTURAL RESOURCES CENTER 1. Larry Murphy. James Baker, David Buller, James Delgado, Rodger Kelly. Daniel Lenihan, David McCulloch, David Pugh; Diana Skiles; Brigid Sullivan. Submerged Cultural Resources Survey: Portions of Point Reyes National Seashore and Point Reyes- Farallon Islands National Marine Sanctuary . Submerged Cultural Resources Unit. 1984. 2. Toni Carrell. Submerged Cultural Resources Inventory: Portions of Point Reyes National Seashore and Point Reyes- Farallon Islands National Marine Sanctuary . Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, 1984. 3. Edwin C. Bearss. Resources Study: Lyndon B. Johnson and the Hill Country, 1937-1963 . Division of Conservation, 1984. 4. Edwin C. Bearss. Historic Structures Report: Texas White House . Division of Conservation, 1986. 5. Barbara Holmes. Historic Resource Study of the Barataria Unit of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park . -

Pueblo Grande Museum ‐ Partial Library Catalog

Pueblo Grande Museum ‐ Partial Library Catalog ‐ Sorted by Title Book Title Author Additional Author Publisher Date 100 Questions, 500 Nations: A Reporter's Guide to Native America Thames, ed., Rick Native American Journalists Association 1998 11,000 Years on the Tonto National Forest: Prehistory and History in Wood, J. Scott McAllister, et al., Marin E. Southwest Natural and Cultural Heritage 1989 Central Arizona Association 1500 Years of Irrigation History Halseth, Odd S prepared for the National Reclamation 1947 Association 1936‐1937 CCC Excavations of the Pueblo Grande Platform Mound Downum, Christian E. 1991 1970 Summer Excavation at Pueblo Grande, Phoenix, Arizona Lintz, Christopher R. Simonis, Donald E. 1970 1971 Summer Excavation at Pueblo Grande, Phoenix, Arizona Fliss, Brian H. Zeligs, Betsy R. 1971 1972 Excavations at Pueblo Grande AZ U:9:1 (PGM) Burton, Robert J. Shrock, et. al., Marie 1972 1974 Cultural Resource Management Conference: Federal Center, Denver, Lipe, William D. Lindsay, Alexander J. Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art, 1974 Colorado Inc. 1974 Excavation of Tijeras Pueblo, Tijeras Pueblo, Cibola National Forest, Cordell, Linda S. U. S.DA Forest Service 1975 New Mexico 1991 NAI Workshop Proceedings Koopmann, Richard W. Caldwell, Doug National Association for Interpretation 1991 2000 Years of Settlement in the Tonto Basin: Overview and Synthesis of Clark, Jeffery J. Vint, James M. Center for Desert Archaeology 2004 the Tonto Creek Archaeological Project 2004 Agave Roast Pueblo Grande Museum Pueblo Grande Museum 2004 3,000 Years of Prehistory at the Red Beach Site CA‐SDI‐811 Marine Corps Rasmussen, Karen Science Applications International 1998 Base, Camp Pendleton, California Corporation 60 Years of Southwestern Archaeology: A History of the Pecos Conference Woodbury, Richard B. -

A History of the Ancient Southwest

A HISTORY OF THE ANCIENT SOUTHWEST one Fore! — Orthodoxies Archaeologies: 1500 to 1850 Histories: “Time Immemorial” to 1500 BC This book is about southwestern archaeology and the ancient Southwest—two very different things. Archaeology is how we learn about the distant past. The ancient Southwest is what actu- ally happened way back then. Archaeology will never disclose or discover everything that happened in the ancient Southwest, but archaeology is our best scholarly way to know any- thing about that distant past. After a century of southwestern archaeology, we know a lot about what happened in the ancient Southwest. We know so much—we have such a wealth of data and information—that much of what we think we know about the Southwest has been necessarily compressed into conventions, classifications, and orthodoxies. This is particularly true of abstract concepts such as Anasazi, Hohokam, and Mogollon. A wall is a wall, a pot is a pot, but Anasazi is… what exactly? This book challenges several orthodoxies and reconfigures others in novel ways—“novel,” perhaps, like Gone with the Wind. I try to stick to the facts, but some facts won’t stick to me. These are mostly old facts—nut-hard verities of past generations. Orthodoxies, shiny from years of handling, slip through fingers and fall through screens like gizzard stones. We can work without them. We already know a few turkeys were involved in the story. Each chapter in this book tells two parallel stories: the development, personalities, and institutions of southwestern archaeology (“archaeologies”) and interpretations of what actu- ally happened in the ancient past (“histories”). -

Human Adaptations and Cultural Change in the Greater Southwest

Human Adaptations and Cultural Change in the Greater Southwest: An Overview of Archeological Resources in the Basin and Range Province by Alan H. Simmons, Ann Lucy Wiener Stodder, Douglas D. Dykeman, and Patricia A. Hicks Prepared by the Desert Research Institute, Quaternary Sciences Center, University of Nevada, Reno, and the Bureau of Anthropological Research, University of Colorado, Boulder, with the Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville. Final Report Submitted to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Southwestern Division. Study Unit 4 of the Southwestern Division Archeological Overview. Contract DACW63-84-C-0149 1989 Academic Press of Orlando, Florida, kindly granted permission for use of a number of figures from Prehistory of the Southwest (Cordell 1984) The Historic Preservation Division, Office of Cultural Affairs, State of New Mexico, kindly granted permission for use of figures from Prehistoric New Mexico (Stuart and Gauthier 1980) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 1-56349-060-9 Arkansas Archeological Survey Fayetteville, Arkansas 72702 Printed in the United States of America, 1989 Second Printing, 1996 New Printing, 2004 Offset Printing by Arkansas Department of Corrections, Wrightsville. Second Printing by University of Arkansas Quick Copy and Printing Services, Fayetteville. New Printing by University of Arkansas Copy Center ii ABSTRACT The archeology of the Region 4, Basin and Range, of the Southwestern Divisions of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is examined in detail. The area included in this study is most of New Mexico and parts of south-central Colorado and the Trans-Pecos region of Texas. This area represents one of the richest archeological regions in the United States. -

A Functional Analysis of Yadkin Bifaces in the Middle Savannah River Valley Jessica M

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 A Functional Analysis of Yadkin Bifaces in the Middle Savannah River Valley Jessica M. Cooper University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, J. M.(2017). A Functional Analysis of Yadkin Bifaces in the Middle Savannah River Valley. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4148 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS OF YADKIN BIFACES IN THE MIDDLE SAVANNAH RIVER VALLEY by Jessica M. Cooper Bachelor of Arts George Mason University, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the ReQuirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: Joanna Casey, Director of Thesis Donald Stephenson, Reader Courtney Lewis, Reader Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Jessica M. Cooper, 2017 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION For Gabriel, without your endless optimism and encouragement this would not have been possible. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are so many people who helped make this thesis possible. I must begin by thanking my son, Gabriel Webb, for all the sacrifices he made during the writing of this thesis. My sister Shannon Corda was invaluable to me during this entire process. Shannon provided boundless encouragement and feedback. -

Burial in Florida: Culture, Ritual, Health, and Status: the Archaic to Seminole Periods David Klingle

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Burial in Florida: Culture, Ritual, Health, and Status: The Archaic to Seminole Periods David Klingle Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] The Florida State University College of Arts and Sciences Burial in Florida: Culture, Ritual, Health, and Status: The Archaic to Seminole Periods David Klingle A Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Klingle defended on February 24, 2006. Glen H. Doran Professor Directing Thesis Rochelle A. Marrinan Committee Member William Parkinson Committee Member Approved: Dean Falk, Chair, Department of Anthropology The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Glen H. Doran and Dr. Rochelle A. Marrinan of Florida State University for all their patience, input, and hard work in helping me to compose this thesis. They were always there to answer questions, listen to my problems, suggest or even provide sources of data, and give me advice on new approaches to my material. Furthermore, I should acknowledge my copy editor Kathleen Wood for reading over the entire thesis and finding all the typos I missed. I would like to recognize the works of several authors who inspired this thesis. Dr Jerome Rose and Richard Steckel for their book, “The Backbone of History.” It helped to influence my methodology to create my status and heath indexes. -

Ancient Americans Once Used a Spear-Thrower Known As an Atlatl for Hunting and Combat

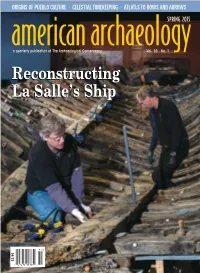

ORIGINSBANNER OF PUEBLO BANNER CULTURE BANNER • CELESTIAL • BANNER TIMEKEEPING BANNER BANNER • ATLATLS • BANNER TO BOWS BANNER AND ARROWS american archaeologySPRING 2015 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 19 No. 1 ReconstructingReconstructing LaLa Salle’sSalle’s ShipShip $3.95 $3.95 SPRING 2015 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 19 No. 1 COVER FEATURE 12 VIVE LA BELLE BY ELIZABETH LUNDAY 39 Due to a long and extraordinary project, the remnants of La Salle’s 17th-century vessel have been preserved. Now the ship is being reconstructed. 19 FROM ATLATLS TO ARROWS BY MIKE TONER The introduction of the bow and arrow in ancient North America had huge consequences. 26 SEARCHING FOR THE ORIGINS OF PUEBLO CULTURE BY TAMARA STEWART The Dillard site is revealing evidence of Pueblo culture’s beginnings. 32 CELESTIAL TIMEKEEPING BY DAVID MALAKOFF LIZ LOPEZ PHOTOGRAPHY The movement of celestial bodies helped ancient people track time. 39 THE SEARCH FOR MOHO BY CHARLES C. POLING 26 In 1541, Coronado led an attack on a Native American pueblo the Spanish called Moho. Historical accounts of this important battle’s location are vague, but several researchers, all focused on different sites, believe they’ve found it. AL CENTER AL 46 point acquisition C CONSERVANCY TO ACQUIRE ITS LARGEST PRESERVE HAEOLOGI IN THE EAST C R Queen Esther’s Town and several A other sites will be saved. CROW CANYON 2 LAY OF THE LAND 50 FiELD NOTES 52 REVIEWS 54 EXPEDITIONS 3 LETTERS 5 EVENTS COVER: Peter Fix (foreground) and Jim Bruseth reassemble 7 IN THE NEWS the hull timbers of La Belle, the ship of the French • Norse Metalworking In Canada explorer Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle.