Campaign Trail 2010 (2): Baghlan - Divided We Stand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conflict Analysis: Baharak District, Badakhshan Province

Conflict analysis: Baharak district, Badakhshan province ACKU Cole Hansen, Christian Dennys and Idrees Zaman CPAU February 2009 Cooperation for Peace and Unity Acknowledgment The conflict analysis is one of 5 provincial studies focusing on Badakhshan, Kunduz, Kabul, Wardak and Ghazni conducted by CPAU with the financial support of Trocaire. The views expressed in the papers are the sole responsibility of CPAU and the authors and are not necessarily held by Trocaire. The principal researcher for this provincial study of Badakhshan would like to thank the other members of the research team in London for their support and the CPAU staff in Kabul who collected the primary data from the field and offered feedback on successive drafts of the study. Copies of this paper can be downloaded from www.cpau.org.af For further information or to contact CPAU please email: Idrees Zaman [email protected] Christian Dennys [email protected] ACKU Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Definitions and Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Primary sources ................................................................................................................................................. -

Afghanistan Earthquake Information Bulletin No.1

AFGHANISTAN: EARTHQUAKE 26 March 2002 Information Bulletin N° 1/2002 This Bulletin is being issued based on the information available at this time. The Federation is currently not seeking international assistance. However, depending on further updates and assessment reports, an appeal may be launched to assist the Afghan Red Crescent Society in its relief operation. The Situation A series of earthquakes - registering up to 6.2 on the Richter scale - struck the Nahrin district of Baghlan province in northern Afghanistan overnight. Unconfirmed reports put the death toll from 100 to as high as 1,800 people, with 5,000 people injured. It is also estimated that 10,000 people have been displaced and 4,000 houses destroyed. Nahrin, which has a population of 82,916, was reported to be 85% destroyed. The region is 160 km east of Mazar-i-Sharif over difficult terrain in the Hindu Kush. Red Cross/Red Crescent action The Afghan Red Crescent Society (ARCS) and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies have made available a stock of relief items for dispatch with a UN convoy due to leave Mazar-i-Sharif later today. The stock - which includes tents, blankets, kitchen sets and jerry cans - is sufficient for 5,000 families. A Red Crescent health emergency mobile unit, equipped with medical supplies, is due to arrive in Nahrin later today. Because of the confusing nature of early reports, the team will not only provide immediate medical assistance but also verify the extent of the disaster in terms of numbers affected and most pressing needs. -

The ANSO Report (16-30 September 2010)

The Afghanistan NGO Safety Office Issue: 58 16-30 September 2010 ANSO and our donors accept no liability for the results of any activity conducted or omitted on the basis of this report. THE ANSO REPORT -Not for copy or sale- Inside this Issue COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 2-7 The impact of the elections and Zabul while Ghazni of civilian casualties are 7-9 Western Region upon CENTRAL was lim- and Kandahar remained counter-productive to Northern Region 10-15 ited. Security forces claim extremely volatile. With AOG aims. Rather it is a that this calm was the result major operations now un- testament to AOG opera- Southern Region 16-20 of effective preventative derway in various parts of tional capacity which al- Eastern Region 20-23 measures, though this is Kandahar, movements of lowed them to achieve a unlikely the full cause. An IDPs are now taking place, maximum of effect 24 ANSO Info Page AOG attributed NGO ‘catch originating from the dis- (particularly on perceptions and release’ abduction in Ka- tricts of Zhari and Ar- of insecurity) for a mini- bul resulted from a case of ghandab into Kandahar mum of risk. YOU NEED TO KNOW mistaken identity. City. The operations are In the WEST, Badghis was The pace of NGO incidents unlikely to translate into the most affected by the • NGO abductions country- lasting security as AOG wide in the NORTH continues onset of the elections cycle, with abductions reported seem to have already recording a three fold in- • Ongoing destabilization of from Faryab and Baghlan. -

AFGHANISTAN – North-Eastern Region Baghlan Humanitarian Team Meeting 16 May 2012 at UNAMA Puli Khumri Office

AFGHANISTAN – North-Eastern Region Baghlan Humanitarian Team Meeting 16 May 2012 at UNAMA Puli Khumri office Draft Minutes Participants: ACTED, AKF-A, FOCUS, Global Partners, Hungarian Embassy, IOM, NRC, OCHA (Chair), UNAMA, USAID, WFP, apologies: IOM (assessment) Agenda: Welcome and introduction Flood emergencies: assessments, response coordination, concerns, gaps Conflict displacement Cluster coordination and resource mobilization Way forward 1. Welcome and introduction OCHA welcomed participants. Participants introduced themselves and informed about type of work they are doing in the province. Global Partners: community development, WASH (septic systems), retaining walls, education, implementing partner of WFP for cash and voucher in Samangan province. ACTED: works in Burka district. AKF-A: works in several districts. Focus: works in Dushi and other districts 2. Flood emergencies On 10 May 2012, a new flood has affected 9 areas of Baghlan province. A Provincial Disaster Management Committee (PDMC) was held in Puli Khumri on 11 May. It has assigned assessment teams. As of early 16 May, assessment results are available for two districts: Burka district (232 affected families) and Dahana-i-Ghuri (68 affected families). Assessment and distribution procedures: ANDMA, the Afghan National Disaster Management Committee, is the designated body within the Government to address natural disasters. In this capacity, ANDMA Baghlan provides secretarial support to the Provincial Disaster Management Committee (PDMC). The PDMC assigns joint assessment teams and approves assessment reports. Based on it ANDMA prepares an official government relief request which is then forwarded to UN agencies and NGOs for assistance. The relief request should include beneficiary lists. Normally, beneficiary lists are drawn up during assessments. -

People of Ghazni

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies [email protected] Updated: June 1, 2010 Province: Baghlan Governor: Munshi Abdul Majid Deputy Governor: Sheikh Baulat (Deceased as a result of February 2008 auto accident) Provincial Police Chief: Abdul Rahman Sayedkhali PRT Leadership: Hungary Population Estimate: 1 Urban: 146,000 Rural: 616,500 Area in Square Kilometers: 21,112 sq. km Capital: Puli Khumri Names of Districts: Kahmard, Tala Wa Barfak, Khinjan, Dushi, Dahana-i-Ghori, Puli Khumri, Andarab, Nahrin, Baghlan, Baghlani Jadid, Burka, Khost Wa Firing Composition of Ethnic Groups: Religious Tribal Groups: Population:2 Tajik: 52% Groups: Gilzhai Pashtun 20% Pashtun: 20% Sunni 85% Hazara: 15% Shi'a 15% Uzbek: 12% Tatar: 1% Income Generation Major: Minor: Agriculture Factory Work Animal Husbandry Private Business (Throughout Province) Manual Labor (In Pul-i-Khomri District) Crops/Farming/Livestock: Agriculture: Livestock: Major: Wheat, Rice Dairy and Beef Cows Secondary: Cotton, Potato, Fodder Sheep (wool production) Tertiary: Consumer Vegetables Poultry (in high elevation Household: Farm Forestry, Fruits areas) Literacy Rate Total:3 20% Number of Educational Schools: Colleges/Universities: 2 Institutions:4 Total: 330 Baghlan University-Departments of Primary: 70 Physics, Social Science and Literature Lower Secondary: 161 in Pul-e-Khumri. Departments of Higher Secondary: 77 Agriculture and Industry in Baghlan Islamic: 19 Teacher Training Center-located in Tech/Vocational: 2 Pul-e-Khumri University: 1 Number of Security January: 3 May: 0 September: 1 Incidents, 2007: 8 February: 0 June: 0 October: 0 March: 0 July: 0 November: 2 April: 2 August: 0 December: 0 Poppy (Opium) Cultivation:5 2006: 2,742 ha 2007: 671 ha NGOs Active in Province: UNHCR, FAO, WHO, IOM, UNOPS, UNICEF, ANBP, ACTED, AKF/AFDN, CONCERN, HALO TRUST, ICARDA, SCA, 1 Central Statistics Office Afghanistan, 2005-2006 Population Statistics, available from http://www.cso- af.net/cso/index.php?page=1&language=en (accessed May 7, 2008). -

Afghanistan: Annual Report 2014

AFGHANISTAN ANNUAL REPORT 2014 PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT © 2014/Ihsanullah Mahjoor/Associated Press United Nations Assistance Mission United Nations Office of the High in Afghanistan Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan February 2015 Kabul, Afghanistan July 2014 Source: UNAMA GIS January 2012 AFGHANISTAN ANNUAL REPORT 2014 PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT United Nations Assistance Mission United Nations Office of the High in Afghanistan Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan February 2015 Photo on Front Cover © 2014/Ihsanullah Mahjoor/Associated Press. Bodies of civilians killed in a suicide attack on 23 November 2014 in Yahyakhail district, Paktika province that caused 138 civilian casualties (53 killed including 21 children and 85 injured including 26 children). Photo taken on 24 November 2014. "The conflict took an extreme toll on civilians in 2014. Mortars, IEDs, gunfire and other explosives destroyed human life, stole limbs and ruined lives at unprecedented levels. The thousands of Afghan children, women and men killed and injured in 2014 attest to failures to protect civilians from harm. All parties must uphold the values they claim to defend and make protecting civilians their first priority.” Nicholas Haysom, United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary-General in Afghanistan, December 2014, Kabul “This annual report shows once again the unacceptable price that the conflict is exacting on the civilian population in Afghanistan. Documenting these trends should not be regarded -

Impacts of Climate Change on the Water Resources of the Kunduz River Basin, Afghanistan

climate Article Impacts of Climate Change on the Water Resources of the Kunduz River Basin, Afghanistan Noor Ahmad Akhundzadah 1,*, Salim Soltani 2 and Valentin Aich 3 1 Faculty of Environment, University of Kabul, Kart-e-Sakhi, Kabul 1001, Afghanistan 2 Institute for Geography and Geology, University of Würzburg, Am Hubland, 97074 Würzburg, Germany; [email protected] 3 Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), Am Telegraphenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +93-(0)-707083359 Received: 30 August 2020; Accepted: 16 September 2020; Published: 23 September 2020 Abstract: The Kunduz River is one of the main tributaries of the Amu Darya Basin in North Afghanistan. Many communities live in the Kunduz River Basin (KRB), and its water resources have been the basis of their livelihoods for many generations. This study investigates climate change impacts on the KRB catchment. Rare station data are, for the first time, used to analyze systematic trends in temperature, precipitation, and river discharge over the past few decades, while using Mann–Kendall and Theil–Sen trend statistics. The trends show that the hydrology of the basin changed significantly over the last decades. A comparison of landcover data of the river basin from 1992 and 2019 shows significant changes that have additional impact on the basin hydrology, which are used to interpret the trend analysis. There is considerable uncertainty due to the data scarcity and gaps in the data, but all results indicate a strong tendency towards drier conditions. An extreme warming trend, partly above 2 ◦C since the 1960s in combination with a dramatic precipitation decrease by more than 30% lead to a strong decrease in river discharge. -

AFGHANISTAN EARTHQUAKE 5 November 2002

AFGHANISTAN EARTHQUAKE 5 November 2002 Appeal No. 10/02 Appeal launched on 12 April 2002 for CHF 2,921,000 for nine months. Operations Update No. 2; Period covered: 1 June - 31 October 2002. Last operations update issued on 1 June 2002. “At a Glance” Appeal coverage: 77.9% Related Appeals: Appeal 32/01 Afghan crisis Outstanding needs: CHF 644,688 In summary: The Afghan Red Crescent was among the first on the scene to assist locals when a devastating earthquake hit Nahrin. The National Society, with Federation support, has maintained this engagement with vulnerable people and is now working with them in key rehabilitation projects, particularly in health and education. Operational Developments Following the earthquake, which devastated the city of Nahrin in Baghlan Province on 25 March killing some 800 and leaving 10,000 homeless, The Federation launched the Afghanistan Earthquake Appeal (no.10/02) on 12 April 2002. Nahrin District, is 74 km (2.5 hours) from Puli-Khumri, which is the main city of the Province, and 264 km (5.5 hours) from Mazar-i-Sharif. The district consists of approximately 90 villages. The largest, and most affected by the earthquake, are Nahrin New and Old City, 5km apart, and the village of Jilga. Nahrin District has a population of approximately 10,000 families. Virtually all needs were covered by the emergency relief operation within ten days after the disaster. The Afghan Red Crescent Society (ARCS) health emergency mobile unit (EMU) was on the scene within 24 hours of the earthquake providing emergency health care to people. -

Lead Inspector General for Operation Freedom's Sentinel April 1, 2021

OFS REPORT TO CONGRESS FRONT MATTER OPERATION FREEDOM’S SENTINEL LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS APRIL 1, 2021–JUNE 30, 2021 FRONT MATTER ABOUT THIS REPORT A 2013 amendment to the Inspector General Act established the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) framework for oversight of overseas contingency operations and requires that the Lead IG submit quarterly reports to Congress on each active operation. The Chair of the Council of Inspectors General for Integrity and Efficiency designated the DoD Inspector General (IG) as the Lead IG for Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). The DoS IG is the Associate IG for the operation. The USAID IG participates in oversight of the operation. The Offices of Inspector General (OIG) of the DoD, the DoS, and USAID are referred to in this report as the Lead IG agencies. Other partner agencies also contribute to oversight of OFS. The Lead IG agencies collectively carry out the Lead IG statutory responsibilities to: • Develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight of the operation. • Ensure independent and effective oversight of programs and operations of the U.S. Government in support of the operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, investigations, and evaluations. • Report quarterly to Congress and the public on the operation and activities of the Lead IG agencies. METHODOLOGY To produce this quarterly report, the Lead IG agencies submit requests for information to the DoD, the DoS, USAID, and other Federal agencies about OFS and related programs. The Lead IG agencies also gather data and information from other sources, including official documents, congressional testimony, policy research organizations, press conferences, think tanks, and media reports. -

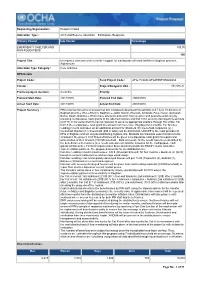

2015 2Nd Reserve Allocation – Earthquake Response Direct

Requesting Organization : People In Need Allocation Type : 2015 2nd Reserve Allocation – Earthquake Response Primary Cluster Sub Cluster Percentage EMERGENCY SHELTER AND 100.00 NON-FOOD ITEMS 100 Project Title : Emergency cash and winterized NFI support for Earthquake affected families in Baghlan province, Afghanistan Allocation Type Category : Core activities OPS Details Project Code : Fund Project Code : AFG-15/3481/AFG/ESNFI/INGO/464 Cluster : Project Budget in US$ : 391,576.13 Planned project duration : 4 months Priority: Planned Start Date : 20/11/2015 Planned End Date : 20/03/2016 Actual Start Date: 20/11/2015 Actual End Date: 20/03/2016 Project Summary : PIN’s intervention aims to ensure that 401 completely destroyed households (CAT A) in 10 districts of Baghlan province (Pul-e-Khumri, Baghlan-e-Jadid, Nahrin, Khenjan, Andarab, Pul-e-Hesar, Dehsalah, Burka, Doshi, Dahana-e-Ghori) have adequate protection from weather and guaranteed privacy by providing multipurpose cash grants to the affected families and that 1033 severely damaged households (CAT B) in the same districts can be repaired to serve as appropriate shelters through the winter. For CAT A the multipurpose cash grant the amount can cover fuel (7kg/day) for 4 months. For families residing in tents and open air an additional amount for (blankets (3)/ household, tarpaulins (2) / household, Bukhari (1) / household (90$ in total)) will be distributed. UNICEF is the main provider of NFIs in Baghlan and will only be distributing hygiene kits. Blankets are therefore essential items to be included in the project. CAT B beneficiaries will be given a multipurpose cash grant for repairs and winterization of their shelters (150 $/household – BoQ annexed). -

End of Year Report (2018) About Mujahideen Progress and Territory Control

End of year report (2018) about Mujahideen progress and territory control: The Year of Collapse of Trump’s Strategy 2018 was a year that began with intense bombardments, military operations and propaganda by the American invaders but all praise belongs to Allah, it ended with the neutralization of another enemy strategy. The Mujahideen defended valiantly, used their chests as shields against enemy onslaughts and in the end due to divine assistance, the invaders were forced to review their war strategy. This report is based on precise data collected from concerned areas and verified by primary sources, leaving no room for suspicious or inaccurate information. In the year 2018, a total of 10638 attacks were carried out by Mujahideen against invaders and their hirelings from which 31 were martyr operations which resulted in the death of 249 US and other invading troops and injuries to 153 along with death toll of 22594 inflicted on Kabul administration troops, intelligence operatives, commandos, police and Arbakis with a further 14063 sustaining injuries. Among the fatalities 514 were enemy commanders killed and eliminated in various attacks across the country. During 2018 a total of 3613 vehicles including APCs, pickup trucks and other variants were destroyed along with 26 aircrafts including 8 UAVs, 17 helicopters of foreign and internal forces and 1 cargo plane shot down. Moreover, a total of 29 district administration centers were liberated by the Mujahideen of Islamic Emirate over the course of last year, among which some were retained -

The Taliban Beyond the Pashtuns Antonio Giustozzi

The Afghanistan Papers | No. 5, July 2010 The Taliban Beyond the Pashtuns Antonio Giustozzi Addressing International Governance Challenges The Centre for International Governance Innovation The Afghanistan Papers ABSTRACT About The Afghanistan Papers Although the Taliban remain a largely Pashtun movement in terms of their composition, they have started making significant inroads among other ethnic groups. In many The Afghanistan Papers, produced by The Centre cases, the Taliban have co-opted, in addition to bandits, for International Governance Innovation disgruntled militia commanders previously linked to other (CIGI), are a signature product of CIGI’s major organizations, and the relationship between them is far research program on Afghanistan. CIGI is from solid. There is also, however, emerging evidence of an independent, nonpartisan think tank that grassroots recruitment of small groups of ideologically addresses international governance challenges. committed Uzbek, Turkmen and Tajik Taliban. While Led by a group of experienced practitioners and even in northern Afghanistan the bulk of the insurgency distinguished academics, CIGI supports research, is still Pashtun, the emerging trend should not be forms networks, advances policy debate, builds underestimated. capacity and generates ideas for multilateral governance improvements. Conducting an active agenda of research, events and publications, CIGI’s interdisciplinary work includes collaboration with policy, business and academic communities around the world. The Afghanistan Papers are essays authored by prominent academics, policy makers, practitioners and informed observers that seek to challenge existing ideas, contribute to ongoing debates and influence international policy on issues related to Afghanistan’s transition. A forward-looking series, the papers combine analysis of current problems and challenges with explorations of future issues and threats.