Afghanistan: Annual Report 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Updated 02.03.2021 an Annotated List of Afghanistan Longhorn Beetles

Updated 02.03.2021 An annotated list of Afghanistan Longhorn beetles (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae) M.A. Lazarev The list is based on the publication by M. A. Lazarev, 2019: Catalogue of Afghanistan Longhorn beetles (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae) with two descriptions of new Phytoecia (Parobereina Danilevsky, 2018) from Central Asia. - Humanity space. International almanac, 8 (2): 104-140.It is regularly updated as new taxa are described (marked with red). Family CERAMBYCIDAE Latreille, 1802 subfamily Prioninae Latreille, 1802 tribe Macrotomini J. Thomson, 1861 genus Anomophysis Quentin & Villiers, 1981: 374 type species Prionus spinosus Fabricius, 1787 inscripta C.O. Waterhouse, 1884: 380 (Macrotoma) Heyrovský, 1936: 211 - Wama; Tippmann, 1958: 41 - Kabul, Ost-Afghanistan, 1740; Sarobi, am Kabulflus, 900 m; Mangul, Bashgultal, Nuristan, Ost-Afghanistan, 1250 m; Fuchs, 1961: 259 - Sarobi 1100 m, O.- Afghanistan; Fuchs, 1967: 432 - Afghanistan, 25 km N von Barikot, 1800 m, Nuristan; Nimla, 40 km SW von Dschelalabad; Heyrovský, 1967: 156 - Zentral-Afghanistan, Prov. Kabul: Kabul; Kabul-Zahir; Ost- Afghanistan, Prov. Nengrahar: “Nuristan”, ohne näheren Fundort; Kamu; Löbl & Smetana, 2010: 90 - Afghanistan. plagiata C.O. Waterhouse, 1884: 381 (Macrotoma) vidua Lameere, 1903: 167 (Macrotoma) Quentin & Villiers, 1981: 361, 376, 383 - Afghanistan: Kaboul; Sairobi; Darah-i-Nour, Nangahar; Löbl & Smetana, 2010: 90 - Afghanistan; Kariyanna et al., 2017: 267 - Afghanistan: Kaboul; Rapuzzi et al., 2019: 64 - Afghanistan. tribe Prionini Latreille, 1802 genus Dorysthenes Vigors, 1826: 514 type species Prionus rostratus Fabricius, 1793 subgenus Lophosternus Guérin-Méneville, 1844: 209 type species Lophosternus buquetii Guérin- Méneville, 1844 Cyrtosternus Guérin-Méneville, 1844: 210 type species Lophosternus hopei Guérin-Méneville, 1844 huegelii L. Redtenbacher, 1844: 550 (Cyrtognathus) falco J. -

Combat Camera Weekly Regional Command-East Afghanistan

Combat Camera Weekly Regional Command-East Afghanistan 5 – 11 JANUARY 2013 U.S. Army Master Sgt. Lynwood Rabon gives instructions to the competitors of a U.S. Army versus Czech Army stress fire range competition on Forward Operating Base Shank, Jan. 5, 2013, Logar province, Afghanistan. Rabon is assigned to Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Alexandra Campo/Released) U.S. Army Master Sgt. Lynwood Rabon gives instructions to the competitors of a U.S. Army versus Czech Army stress fire range competition on Forward Operating Base Shank, Jan. 5, 2013, Logar province, Afghanistan. Rabon is assigned to Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Alexandra Campo/Released) U.S. Army Col. Andrew Rohling competes at a U.S. Army versus Czech Army stress fire range on Forward Operating Base Shank, Jan. 5, 2013, Logar province, Afghanistan. Rohling is the commander of the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Alexandra Campo/Released) U.S. Army Col. Andrew Rohling competes at a U.S. Army versus Czech Army stress fire range on Forward Operating Base Shank, Jan. 5, 2013, Logar province, Afghanistan. Rohling is the commander of the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Alexandra Campo/Released) U.S. Army Col. Andrew Rohling competes at a U.S. Army versus Czech Army stress fire range on Forward Operating Base Shank, Jan. 5, 2013, Logar province, Afghanistan. Rohling is the commander of the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team. -

The ANSO Report (16-30 September 2010)

The Afghanistan NGO Safety Office Issue: 58 16-30 September 2010 ANSO and our donors accept no liability for the results of any activity conducted or omitted on the basis of this report. THE ANSO REPORT -Not for copy or sale- Inside this Issue COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 2-7 The impact of the elections and Zabul while Ghazni of civilian casualties are 7-9 Western Region upon CENTRAL was lim- and Kandahar remained counter-productive to Northern Region 10-15 ited. Security forces claim extremely volatile. With AOG aims. Rather it is a that this calm was the result major operations now un- testament to AOG opera- Southern Region 16-20 of effective preventative derway in various parts of tional capacity which al- Eastern Region 20-23 measures, though this is Kandahar, movements of lowed them to achieve a unlikely the full cause. An IDPs are now taking place, maximum of effect 24 ANSO Info Page AOG attributed NGO ‘catch originating from the dis- (particularly on perceptions and release’ abduction in Ka- tricts of Zhari and Ar- of insecurity) for a mini- bul resulted from a case of ghandab into Kandahar mum of risk. YOU NEED TO KNOW mistaken identity. City. The operations are In the WEST, Badghis was The pace of NGO incidents unlikely to translate into the most affected by the • NGO abductions country- lasting security as AOG wide in the NORTH continues onset of the elections cycle, with abductions reported seem to have already recording a three fold in- • Ongoing destabilization of from Faryab and Baghlan. -

Understanding Afghanistan

Understanding Afghanistan: The Importance of Tribal Culture and Structure in Security and Governance By Shahmahmood Miakhel US Institute of Peace, Chief of Party in Afghanistan Updated November 20091 “Over the centuries, trying to understand the Afghans and their country was turned into a fine art and a game of power politics by the Persians, the Mongols, the British, the Soviets and most recently the Pakistanis. But no outsider has ever conquered them or claimed their soul.”2 “Playing chess by telegraph may succeed, but making war and planning a campaign on the Helmand from the cool shades of breezy Shimla (in India) is an experiment which will not, I hope, be repeated”.3 Synopsis: Afghanistan is widely considered ungovernable. But it was peaceful and thriving during the reign of King Zahir Shah (1933-1973). And while never held under the sway of a strong central government, the culture has developed well-established codes of conduct. Shuras (councils) and Jirgas (meeting of elders) appointed through the consensus of the populace are formed to resolve conflicts. Key to success in Afghanistan is understanding the Afghan mindset. That means understanding their culture and engaging the Afghans with respect to the system of governance that has worked for them in the past. A successful outcome in Afghanistan requires balancing tribal, religious and government structures. This paper outlines 1) the traditional cultural terminology and philosophy for codes of conduct, 2) gives examples of the complex district structure, 3) explains the role of councils, Jirgas and religious leaders in governing and 4) provides a critical overview of the current central governmental structure. -

Making Sense of Daesh in Afghanistan: a Social Movement Perspective

\ WORKING PAPER 6\ 2017 Making sense of Daesh in Afghanistan: A social movement perspective Katja Mielke \ BICC Nick Miszak \ TLO Joint publication by \ WORKING PAPER 6 \ 2017 MAKING SENSE OF DAESH IN AFGHANISTAN: A SOCIAL MOVEMENT PERSPECTIVE \ K. MIELKE & N. MISZAK SUMMARY So-called Islamic State (IS or Daesh) in Iraq and Syria is widely interpreted as a terrorist phenomenon. The proclamation in late January 2015 of a Wilayat Kho- rasan, which includes Afghanistan and Pakistan, as an IS branch is commonly interpreted as a manifestation of Daesh's global ambition to erect an Islamic caliphate. Its expansion implies hierarchical order, command structures and financial flows as well as a transnational mobility of fighters, arms and recruits between Syria and Iraq, on the one hand, and Afghanistan–Pakistan, on the other. In this Working Paper, we take a (new) social movement perspective to investigate the processes and underlying dynamics of Daesh’s emergence in different parts of the country. By employing social movement concepts, such as opportunity structures, coalition-building, resource mobilization and framing, we disentangle the different types of resource mobilization and long-term conflicts that have merged into the phenomenon of Daesh in Afghanistan. In dialogue with other approaches to terrorism studies as well as peace, civil war and security studies, our analysis focuses on relations and interactions among various actors in the Afghan-Pakistan region and their translocal networks. The insight builds on a ten-month fieldwork-based research project conducted in four regions—east, west, north-east and north Afghanistan—during 2016. We find that Daesh in Afghanistan is a context-specific phenomenon that manifests differently in the various regions across the country and is embedded in a long- term transformation of the religious, cultural and political landscape in the cross-border region of Afghanistan–Pakistan. -

AFGHANISTAN – North-Eastern Region Baghlan Humanitarian Team Meeting 16 May 2012 at UNAMA Puli Khumri Office

AFGHANISTAN – North-Eastern Region Baghlan Humanitarian Team Meeting 16 May 2012 at UNAMA Puli Khumri office Draft Minutes Participants: ACTED, AKF-A, FOCUS, Global Partners, Hungarian Embassy, IOM, NRC, OCHA (Chair), UNAMA, USAID, WFP, apologies: IOM (assessment) Agenda: Welcome and introduction Flood emergencies: assessments, response coordination, concerns, gaps Conflict displacement Cluster coordination and resource mobilization Way forward 1. Welcome and introduction OCHA welcomed participants. Participants introduced themselves and informed about type of work they are doing in the province. Global Partners: community development, WASH (septic systems), retaining walls, education, implementing partner of WFP for cash and voucher in Samangan province. ACTED: works in Burka district. AKF-A: works in several districts. Focus: works in Dushi and other districts 2. Flood emergencies On 10 May 2012, a new flood has affected 9 areas of Baghlan province. A Provincial Disaster Management Committee (PDMC) was held in Puli Khumri on 11 May. It has assigned assessment teams. As of early 16 May, assessment results are available for two districts: Burka district (232 affected families) and Dahana-i-Ghuri (68 affected families). Assessment and distribution procedures: ANDMA, the Afghan National Disaster Management Committee, is the designated body within the Government to address natural disasters. In this capacity, ANDMA Baghlan provides secretarial support to the Provincial Disaster Management Committee (PDMC). The PDMC assigns joint assessment teams and approves assessment reports. Based on it ANDMA prepares an official government relief request which is then forwarded to UN agencies and NGOs for assistance. The relief request should include beneficiary lists. Normally, beneficiary lists are drawn up during assessments. -

Campaign Trail 2010 (2): Baghlan - Divided We Stand

Campaign Trail 2010 (2): Baghlan - Divided we Stand Author : Fabrizio Foschini Published: 7 July 2010 Downloaded: 7 September 2018 Download URL: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/campaign-trail-2010-2-baghlan-divided-we-stand/?format=pdf Situated in a central position crossed by some of the most strategic road connections of the country, Baghlan province shows a high level of social and political fragmentation. The growing instability of the province does not bode well for the oncoming elections, and forecasts future problems for the government and the international forces in the area. With a total of 118 candidates (including 12 women) for just 8 seats in the Wolesi Jirga – only Kabul and Laghman have a similarly high proportion of contenders – Baghlan inhabitants could be easily mistaken for a population of election enthusiasts. However, these high numbers seem to reflect more the fault lines splitting local communities and political groups, which prevented the most basics accords between candidates to take place (*). Looking at past elections, high numbers of candidates are not a new development for Baghlan. In the parliamentary elections of 2005 there were 106, and the number of participants to last year’s provincial council elections is even more striking, reaching 193 candidates for the 15 seats body. Baghlan has been characterized for decades by a high number of different factions struggling to control this rich region’s economic assets and communication links and this is also reflected in the electoral competition. Baghlan is a rich province, with a flourishing agriculture blessed by the water resources of the Baghlan-Kunduz river system and by proximity and good road connections to markets like Kabul and Mazar-e Sharif. -

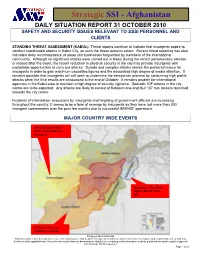

Daily Situation Report 31 October 2010 Safety and Security Issues Relevant to Sssi Personnel and Clients

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan DAILY SITUATION REPORT 31 OCTOBER 2010 SAFETY AND SECURITY ISSUES RELEVANT TO SSSI PERSONNEL AND CLIENTS STANDING THREAT ASSESSMENT (KABUL): Threat reports continue to indicate that insurgents aspire to conduct coordinated attacks in Kabul City, as such the threat remains extant. Recent threat reporting has also indicated likely reconnaissance of areas and businesses frequented by members of the international community. Although no significant attacks were carried out in Kabul during the recent parliamentary election, or indeed after the event, the recent reduction in physical security in the city may provide insurgents with exploitable opportunities to carry out attacks. Suicide and complex attacks remain the preferred choice for insurgents in order to gain maximum casualties figures and the associated high degree of media attention. It remains possible that insurgents will still seek to undermine the democratic process by conducting high profile attacks when the final results are announced at the end of October. It remains prudent for international agencies in the Kabul area to maintain a high degree of security vigilance. Sporadic IDF attacks in the city centre are to be expected. Any attacks are likely to consist of between one and four 107 mm rockets launched towards the city centre. Incidents of intimidation, executions by insurgents and targeting of government officials are increasing throughout the country. It seems to be a form of revenge by insurgents as they have lost more than 300 insurgent commanders over the past few months due to successful IM/ANSF operations. MAJOR COUNTRY WIDE EVENTS Herat: Influencial local Tribal Leader killed by insurgents Nangarhar: Five attacks against Border Police OPs Helmand: Five local residents murdered Privileged and Confidential This information is intended only for the use of the individual or entity to which it is addressed and may contain information that is privileged, confidential, and exempt from disclosure under applicable law. -

PDMC Laghman Meeting Minutes

Laghman Provincial Disaster Management Committee (PDMC) Meeting Minutes Provincial Governor’s Office – Wednesday, 04 March, 2015 Participants: WFP, UNICEF, WHO, NCRO, SERVE, IRC, NRC, MADERA, SCA, IOM, DRC, ARCS, OCHA, ANDMA, ANA, ANP, DRRD, DoPH, DoRR, DoEnvironment, DoEducation, DoPW, DoAIL, Governor’s Office and other government officials. A. Introduction and Opening Remarks of Provincial Governor: On Wednesday 04 October 15, the Provincial Governor (PG) for Laghman called a Provincial Disaster Management Committee meeting (PDMC). After a short round of introductions, the PG welcomed PDMC members, further he extend of condolences with families, lost their family members due to recent rainfall, snowfall/avalanches and flood particularly to the people of Laghman province and he also highlighted on recent natural hazards (Rainfall, Flood and Snowfall) occurred on 25 February, 2015. The PG gratitude from humanitarian community’s efforts for there on timely response to the affected families he also appreciated the ANSAF’s on time action in rescued the people in Mehterlam and Qarghayi districts of Laghman province, especially ANA rescued 90 Nomad people Marooned in Qarghayi district of Laghman. The PG also highlighted on devastation caused by rainfall and flood which lifted 5 killed, 13 injured, about more than 500 families affected, 800 Jirebs or 400 Acores Agriculture land/Crops washed away and about 39 irrigation canal and intakes severely damaged or destroyed. The PG calcified devastations in three categories to facilitate the response for both (Humanitarian Community and Government line departments). 1. Response to Emergency need and saves lives. 2. Mid-terms actions as reactivation of irrigation system (cleaning of intakes and irrigation canal) opening the routs. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Badghis Province

AFGHANISTAN Badghis Province District Atlas April 2014 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info [email protected] AFGHANISTAN: Badghis Province Reference Map 63°0'0"E 63°30'0"E 64°0'0"E 64°30'0"E 65°0'0"E Legend ^! Capital Shirintagab !! Provincial Center District ! District Center Khwajasabzposh Administrative Boundaries TURKMENISTAN ! International Khwajasabzposh Province Takhta Almar District 36°0'0"N 36°0'0"N Bazar District Distirict Maymana Transportation p !! ! Primary Road Pashtunkot Secondary Road ! Ghormach Almar o Airport District p Airfield River/Stream ! Ghormach Qaysar River/Lake ! Qaysar District Pashtunkot District ! Balamurghab Garziwan District Bala 35°30'0"N 35°30'0"N Murghab District Kohestan ! Fa r y ab Kohestan Date Printed: 30 March 2014 08:40 AM Province District Data Source(s): AGCHO, CSO, AIMS, MISTI Schools - Ministry of Education ° Health Facilities - Ministry of Health Muqur Charsadra Badghis District District Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS-84 Province Abkamari 0 20 40Kms ! ! ! Jawand Muqur Disclaimers: Ab Kamari Jawand The designations employed and the presentation of material !! District p 35°0'0"N 35°0'0"N Qala-e-Naw District on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Qala-i-Naw Qadis city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation District District of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Afghanistan Monthly Idp Update

AFGHANISTAN MONTHLY IDP UPDATE 01 – 30 November 2014 KEY FIGURES HIGHLIGHTS --- -------------------- ---------------- - . Region end-Oct 2014 Increase Decrease end-Nov 2014 15,617 individuals, displaced by conflict, were profiled South 207,160 3,050 - 210,210 during November 2014, of West 193,439 4,286 - 197,725 whom: East 134,640 1,030 - 135,670 10,138 individuals were North 100,897 1,785 - 102,682 displaced in November; 2,674 in October; 649 in September; Central 112,081 5,432 - 117,513 1,002 in August; 60 in July; 31 Southeast 18,328 - - 18,328 in June; and 1,063 earlier. Central Highlands - 34 - 34 . The total number of profiled Total 766,545 15,617 - 782,162 IDPs as of end November 2014 is 782,162 individuals. The major causes of displacement were the military operations and armed conflict between Anti Governmental Elements (AGEs) and Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF)/Afghan local police. Other causes included harassments by AGEs. Disaggregated data for November profiled: 49 % male The primary needs profiled was food and NFIs, followed by shelter and cash grants. and 51% female; The majority of the profiled IDPs in November were assisted with food and NFIs, 48% adults and 52% children. through the IDP Task Force agencies including DoRR, DRC, NRC, UNHCR, WFP, APA, ODCG, ACF, etc. PARTNERSHIPS Lack of access to verify displacement and respond to immediate needs of IDPs continues to be a significant challenge for IDP Task Force agencies. The National IDP Task Force is The UNHCR led verification of Kabul informal settlements which was planned for chaired by the Ministry of November is completed.