Security Council Distr.: General 30 May 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muslim Personal Law in India a Select Bibliography 1949-74

MUSLIM PERSONAL LAW IN INDIA A SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY 1949-74 SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Master of Library Science, 1973-74 DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIEVCE, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH. Ishrat All QureshI ROLL No. 5 ENROLMENT No. C 2282 20 OCT 1987 DS1018 IMH- ti ^' mux^ ^mCTSSDmSi MUSLIM PERSONAL LAW IN INDIA -19I4.9 « i97l<. A SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRSMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DESIEE OF MASTER .OF LIBRARY SCIENCE, 1973-7^ DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH ,^.SHRAT ALI QURESHI Roll No.5 Enrolment Nb.C 2282 «*Z know tbt QUaa of Itlui elaiJi fliullty for tho popular sohools of Mohunodan Lav though thoj noror found it potslbla to dany the thaorotloal peasl^Ultj of a eoqplota Ijtlhad. Z hava triad to azplain tha oauaaa ¥hieh,in my opinion, dataminad tbia attitudo of tlia laaaaibut ainca thinga hcra ehangad and tha world of Ulan is today oonfrontad and affaetad bj nav foroaa sat fraa by tha extraordinary davalopaant of huaan thought in all ita diraetiona, I see no reason why thia attitude should be •aintainad any longer* Did tha foundera of our sehools ever elala finality for their reaaoninga and interpreti^ tionaT Navar* The elaii of tha pxasaat generation of Muslia liberala to raintexprat the foundational legal prineipleay in the light of their ovn ej^arla^oe and the altered eonditlona of aodarn lifs is,in wj opinion, perfectly Justified* Xhe teaehing of the Quran that life is a proeasa of progressiva eraation naeaaaltatas that eaoh generation, guided b&t unhampered by the vork of its predeoessors,should be peraittad to solve its own pxbbleas." ZQ BA L '*W« cannot n»gl«ct or ignoi* th« stupandoits vox^ dont by the aarly jurists but «• cannot b« bound by it; v« must go back to tha original sources 9 th« (^ran and tba Sunna. -

Updated 02.03.2021 an Annotated List of Afghanistan Longhorn Beetles

Updated 02.03.2021 An annotated list of Afghanistan Longhorn beetles (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae) M.A. Lazarev The list is based on the publication by M. A. Lazarev, 2019: Catalogue of Afghanistan Longhorn beetles (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae) with two descriptions of new Phytoecia (Parobereina Danilevsky, 2018) from Central Asia. - Humanity space. International almanac, 8 (2): 104-140.It is regularly updated as new taxa are described (marked with red). Family CERAMBYCIDAE Latreille, 1802 subfamily Prioninae Latreille, 1802 tribe Macrotomini J. Thomson, 1861 genus Anomophysis Quentin & Villiers, 1981: 374 type species Prionus spinosus Fabricius, 1787 inscripta C.O. Waterhouse, 1884: 380 (Macrotoma) Heyrovský, 1936: 211 - Wama; Tippmann, 1958: 41 - Kabul, Ost-Afghanistan, 1740; Sarobi, am Kabulflus, 900 m; Mangul, Bashgultal, Nuristan, Ost-Afghanistan, 1250 m; Fuchs, 1961: 259 - Sarobi 1100 m, O.- Afghanistan; Fuchs, 1967: 432 - Afghanistan, 25 km N von Barikot, 1800 m, Nuristan; Nimla, 40 km SW von Dschelalabad; Heyrovský, 1967: 156 - Zentral-Afghanistan, Prov. Kabul: Kabul; Kabul-Zahir; Ost- Afghanistan, Prov. Nengrahar: “Nuristan”, ohne näheren Fundort; Kamu; Löbl & Smetana, 2010: 90 - Afghanistan. plagiata C.O. Waterhouse, 1884: 381 (Macrotoma) vidua Lameere, 1903: 167 (Macrotoma) Quentin & Villiers, 1981: 361, 376, 383 - Afghanistan: Kaboul; Sairobi; Darah-i-Nour, Nangahar; Löbl & Smetana, 2010: 90 - Afghanistan; Kariyanna et al., 2017: 267 - Afghanistan: Kaboul; Rapuzzi et al., 2019: 64 - Afghanistan. tribe Prionini Latreille, 1802 genus Dorysthenes Vigors, 1826: 514 type species Prionus rostratus Fabricius, 1793 subgenus Lophosternus Guérin-Méneville, 1844: 209 type species Lophosternus buquetii Guérin- Méneville, 1844 Cyrtosternus Guérin-Méneville, 1844: 210 type species Lophosternus hopei Guérin-Méneville, 1844 huegelii L. Redtenbacher, 1844: 550 (Cyrtognathus) falco J. -

Salience of Ethnicity Among Burman Muslims: a Study in Identity Formation

INTELLECTUAL DISCOURSE, 2005 VOL 13, N0 2, 161-179 Salience of Ethnicity among Burman Muslims: A Study in Identity Formation Khin Maung Yin∗ Abstract: Muslims, constituting about thirteen percent of the total population of Myanmar or Burma are not a monolithic group and are unable to provide a united front in their struggle to realize their just demands. They are divided into many groups and their relationship with each other is conflictual. As the cases of Indian and Bamar (Burman) Muslims show, they rely upon ethnicity, rather than religion, for identity formation and self-expression. Burma, known as Myanmar since 1989, is the second largest country in ASEAN or South East Asia.1 It stretches nearly 1500 miles from North to South. With an area of 678,500 square km and a population of about 48 million, it lies at the juncture of three regions of Southeast Asia, South Asia and East Asia. It is situated between two Asian giants, India and China, and shares borders with Bangladesh, Thailand and Laos. Burma is more significant than many other countries in the region as it is surrounded, in the southwest and south, by the Indian Ocean, Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea. It lies, in the words of Huntington, across the fault lines of the Hindu, Buddhist and Confucian civilisations.2 Burma or Myanmar is a nation with many races and there are about 135 ethnic groups. Its population is nearly 50 million. The majority are Bamar, but the Shan, Kachin, Kayin, Chin, Mon, Rakhine, Burmese Muslims, Indian Muslims, Chinese Muslims and others are prominent minority groups in Burma. -

Afganistan'in Yeniden Inşasinda Türkiye'nin Rolü

T.C SAKARYA ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ AFGANİSTAN’IN YENİDEN İNŞASINDA TÜRKİYE’NİN ROLÜ (2001-2011) DOKTORA TEZİ Mehmet YILDIZ Enstitü Anabilim Dalı: Uluslararası İlişkiler Enstitü Bilim Dalı : Uluslararası İlişkiler Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Dr. G. Saynur DERMAN OCAK - 2014 ÖNSÖZ Bu tezin yazılması aşamasında, çalışmamı sahiplenerek titizlikle takip eden danışmanım Doç. Dr. G. Saynur Derman’a değerli katkı ve emekleri için içten teşekkürlerimi ve saygılarımı sunarım. Prof. Dr. Mehmet Alpargu ve Yrd. Doç. Dr. Filiz Cicioğlu bütün süreç boyunca her anlamda yanımda olmuş, desteğini ve katkılarını esirgememiştir. Savunma sınavı sırasında jüri üyeleri Prof. Dr. Esra Hatipoğlu ve Doç. Dr. Zeynel Abidin Kılınç da çalışmamın son haline gelmesine değerli katkılar yapmışlardır. Bu vesileyle tüm hocalarıma ve tezimin son okumasında yardımlarını esirgemeyen arkadaşlarıma teşekkürlerimi borç bilirim. Son olarak bu günlere ulaşmamda emeklerini hiçbir zaman ödeyemeyeceğim eşime, anneme ve aileme şükranlarımı sunarım. Mehmet YILDIZ 15.01.2014 İÇİNDEKİLER KISALTMALAR ............................................................................................................ v TABLO LİSTESİ ......................................................................................................... viii ŞEKİL LİSTESİ ............................................................................................................. ix ÖZET ............................................................................................................................... -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Ethnographic Series, Sidhi, Part IV-B, No-1, Vol-V

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUMEV, PART IV-B, No.1 ETHNOGRAPHIC SERIES GUJARAT Preliminary R. M. V ANKANI, investigation Tabulation Officer, and draft: Office of the CensuS Superintendent, Gujarat. SID I Supplementary V. A. DHAGIA, A NEGROID L IBE investigation: Tabulation Officer, Office of the Census Superintendent, OF GU ARAT Gujarat. M. L. SAH, Jr. Investigator, Office of the Registrar General, India. Fieta guidance, N. G. NAG, supervision and Research Officer, revised draft: Office of the Registrar General, India. Editors: R. K. TRIVEDI, Su perintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. B. K. Roy BURMAN, Officer on Special Duty, (Handicrafts and Social Studies), Office of the Registrar General, India. K. F. PATEL, R. K. TRIVEDI Deputy Superintendent of Census Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. Operations, Gujarat N. G. NAG, Research Officer, Office' of the Registrar General, India. CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: '" I-A(i) General Report '" I-A(ii)a " '" I-A(ii)b " '" I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :« I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey :I' I-C Subsidiary Tables '" II-A General Population Tables '" II-B(I) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) '" II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) '" II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :t< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) "'IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments :t<IV-B Housing and Establishment -

Guía Mundial De Oración (GMO). Noviembre 2014 Titulares: Los

Guía Mundial de Oración (GMO). Noviembre 2014 Titulares: Los inconquistables Pashtun! • 1-3 De un ciego que llevó a los Pashtunes Fuera de la Oscuridad • 5 Sobre todo Hospitalidad! • 8 Estilo de Resolución de Conflictos Pashtun • 23 Personas Mohmund: Poetas que alaban a Dios • 24 Estaría de acuerdo con los talibanes sobre esto! Queridos Amigos de oración, Yo soy un inglés, irlandés, y de descendencia sueca. Hace mil ochocientos años, mis antepasados irlandeses eran cazadores de cabezas que bebían la sangre de los cráneos de sus víctimas. Hace mil años mis antepasados vikingos eran guerreros que eran tan crueles cuando allanaban y destruían los pueblos desprotegidos, que hicieron la Edad Media mucho más oscura. Eventualmente la luz del evangelio hizo que muchos grupos de personas se convirtieran a Cristo, el único que es la Luz del Mundo. Su cultura ha cambiado, y comenzaron a vivir más por las enseñanzas de Jesús y menos por los caminos del mundo. La historia humana nos enseña que sin Cristo la humanidad puede ser increíblemente cruel con otros. Este mes vamos a estar orando por los Pashtunes. Puede parecer que estamos juzgando estas tribus afganas y pakistaníes. Pero debemos recordar que sin la obra transformadora del Espíritu Santo, no seríamos diferentes de lo que ellos son. Los Pashtunes tienen un código cultural de honor llamado Pashtunwali, lo que pone un cierto equilibrio de moderación en su conducta, pero también los estimula a mayores actos de violencia y venganza. Por esta razón, no sólo vamos a orar por tribus Pashtunes específicas, sino también por aspectos del código de honor Pashtunwali y otras dinámicas culturales que pueden mantener a los Pashtunes haciendo lo que Dios quiere que hagan. -

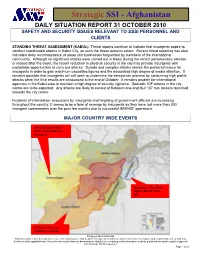

Daily Situation Report 31 October 2010 Safety and Security Issues Relevant to Sssi Personnel and Clients

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan DAILY SITUATION REPORT 31 OCTOBER 2010 SAFETY AND SECURITY ISSUES RELEVANT TO SSSI PERSONNEL AND CLIENTS STANDING THREAT ASSESSMENT (KABUL): Threat reports continue to indicate that insurgents aspire to conduct coordinated attacks in Kabul City, as such the threat remains extant. Recent threat reporting has also indicated likely reconnaissance of areas and businesses frequented by members of the international community. Although no significant attacks were carried out in Kabul during the recent parliamentary election, or indeed after the event, the recent reduction in physical security in the city may provide insurgents with exploitable opportunities to carry out attacks. Suicide and complex attacks remain the preferred choice for insurgents in order to gain maximum casualties figures and the associated high degree of media attention. It remains possible that insurgents will still seek to undermine the democratic process by conducting high profile attacks when the final results are announced at the end of October. It remains prudent for international agencies in the Kabul area to maintain a high degree of security vigilance. Sporadic IDF attacks in the city centre are to be expected. Any attacks are likely to consist of between one and four 107 mm rockets launched towards the city centre. Incidents of intimidation, executions by insurgents and targeting of government officials are increasing throughout the country. It seems to be a form of revenge by insurgents as they have lost more than 300 insurgent commanders over the past few months due to successful IM/ANSF operations. MAJOR COUNTRY WIDE EVENTS Herat: Influencial local Tribal Leader killed by insurgents Nangarhar: Five attacks against Border Police OPs Helmand: Five local residents murdered Privileged and Confidential This information is intended only for the use of the individual or entity to which it is addressed and may contain information that is privileged, confidential, and exempt from disclosure under applicable law. -

Afghanistan: Sikhs and Hindus

Country Policy and Information Note Afghanistan: Sikhs and Hindus Version 5.0 May 2019 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Council Implementing Regulation (EU)

L 82/18 EN Official Journal of the European Union 22.3.2013 COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 261/2013 of 21 March 2013 implementing Article 11(1) and (4) of Regulation (EU) No 753/2011 concerning restrictive measures directed against certain individuals, groups, undertakings and entities in view of the situation in Afghanistan THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, pursuant to paragraph 30 of Security Council Resolution 1988 (2011), updated and amended the list of indi Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European viduals, groups, undertakings and entities subject to Union, restrictive measures. Having regard to Council Regulation (EU) No 753/2011 of (3) Annex I to Regulation (EU) No 753/2011 should be 1 August 2011 concerning restrictive measures directed amended accordingly, against certain individuals, groups, undertakings and entities in view of the situation in Afghanistan ( 1), and in particular HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Article 11(1) and (4) thereof, Article 1 Whereas: Annex I to Regulation (EU) No 753/2011 is hereby amended as set out in the Annex to this Regulation. (1) On 1 August 2011, the Council adopted Regulation (EU) No 753/2011. Article 2 (2) On 11 February and 25 February 2013, the United This Regulation shall enter into force on the day of its Nations Security Council Committee, established publication in the Official Journal of the European Union. This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States. Done at Brussels, 21 March 2013. For the Council The President P. HOGAN ( 1 ) OJ L 199, 2.8.2011, p. -

3. (SINF) JTF GTMO Assessment

SECRET 20300527 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE JOINT TASK FORCE GUANTANAMO GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA APO AE 09360 GTMO- CG 27 May 2005 MEMORANDUMFORCommander, United States Southern Command, 3511NW Avenue, Miami, FL 33172 SUBJECT: UpdateRecommendationto Retainin DoDControl( ) for Guantanamo Detainee, ISN: US9AF-001002DP(S) JTF GTMO DetaineeAssessment 1. (FOUO) Personal Information: JDIMS NDRC Reference Name: AbdulMateen Aliases and Current/ True Name: Qari AbdulMateen, Mullah Shahzada, Qari AbdulMatin Shahzada Mohommad Nabi, Abdul Matin Place of Birth: Tanka Village Jowzjan Province/ Afghanistan (AF) Date of Birth: January 1965 Citizenship: Afghanistan InternmentSerial Number (ISN) : US9AF-001002DP 2. (FOUO) Health Detainee is in good health. Detainee has no travel restrictions. 3. ( SI NF) JTF GTMO Assessment : a . (S ) Recommendation : JTF GTMO recommends this detainee be Retained in Control ( . b . ( SI/NF) Summary: JTF GTMO previously assessed detainee as Transfer to the Control of Another Country for Continued Detention ( TRCD ) on 29 March 2004. Based upon information obtained since detainee's previous assessment, it is now recommended he be Retained in DoD Control ( . CLASSIFIED BY: MULTIPLE SOURCES REASON: E.O. 12958 SECTION 1.5 (C ) DECLASSIFY ON : 20300527 SECRET//NOFORN 20300527 SECRETI // 20300527 JTF GTMO-CG SUBJECT: UpdateRecommendationto Retainin DoD Control( for Guantanamo Detainee, ISN: -001002DP(S) For this update recommendation, detainee is assessed as a member of the Taliban intelligence network . Detainee was an assistant to the Mazar - E -Sharif Taliban Intelligence Chief, Sharifuddin ( Sharafat). During a period when Sharifuddin (Sharafat) was ill, the detainee temporarily commanded the intelligence organization inMazar- E -Sharif, AF . During this period, detainee ordered the local population to disarm , and he is accused of having the Mayor of Mazar- E -Sharif, Alam Khan, assassinated.