Early Cinema in the Ottoman Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

Behice Tezçakar Özdemir [email protected]

CURRICULUM VITÆ Turkish-German University Faculty of Economics & Administrative Sciences Department of Political Sciences and International Relations POL 550-551 Behice Tezçakar Özdemir www.behiceozdemir.com [email protected] General Overview Behice Tezçakar Özdemir who is an author, history researcher, professional expert on industry history and journalist born and raised in Bosphorus (Istanbul). She received her B.A in History as a valedictorian of Istanbul Bilgi University. She got the Master’s Degree from History Department of Boğaziçi University. She specialized on the Turkish- German industrial relations and the roles of German enterprises and companies on the industrial developments of Ottoman territories including today’s Turkey, Middle East and Balkans. Her research book ‘Discovery of Oil in the Minds and Lands of the Ottoman Empire’ is published internationally (2009). Özdemir is co-writer for ‘Daheim in Konstantinopel-Deutch Spuren am Bosporus ab 1850- Memleketimiz Dersaadet 1850’den itibaren Boğaziçi’nde Alman izleri’ published by Pagma Verlag in Germany (2013). Her last research book ‘History of Siemens from Empire to Republic - In the Light of Documents from State Archives’ was published for Siemens 160th anniversary (2016). In that work she examined different territories of Ottoman Empire like Constantinople, Baghdad, Basra, Fao, Sudan, Mosul, Aleppo, Tripoli, Rhodes, Thessalonica on behalf of the industrial activities in different sectors like communications, mobility, energy and industry, defense, cities and building technologies, human resources and healthcare. In 2018, she conducted the research project of Thyssen Krupp and she prepared a book that covered the defense, iron and steel industry services of the Germans through the company of Thyssen Krupp, in Ottoman lands (in the Balkans, Asia Minor, the Middle East and North Africa ) during the Prussian period. -

Enver Paşa Enver Pasha 1881-1922 Ernestine Reiser

kim kimdir? who is who? 401 Enver Paşa Enver Pasha 1881-1922 İstanbul doğumlu, Gagavuz kökenli Osmanlı askeri, Born in Istanbul, Ottoman soldier of Gagauz origin. While still siyasetçi. İkincilikle bitirdiği Harbiye’de henüz öğrenciyken a student at the Military Academy, from which he graduated “devleti kurtarma” idealiyle siyasete eğilim göstermeye ranking the second, he started to get involved in politics with başladı (1902). 1908’de subay arkadaşlarıyla birlikte, Sultan the ideal of “saving the country” (1902). In 1908, he joined his II. Abdülhamid iktidarına meşruti yönetim gayesiyle military peers in the demand for constitutional régime and took başkaldırıp dağa çıktı. İhtilalin ardından 1909’da ilan edilen to the mountains to revolt against Sultan Abdülhamid II. He meşruti idarenin en aktif ismi oldu. İttihat ve Terakki was the most active figure in the constitutional administration Partisi’nin liderlerindendi. Hem ordunun hem siyasetin announced after the coup, in 1909. He was one of the leaders parlak ismiydi. Sultan Abdülmecid’in torunu Naciye Sultan of the Union and Progress Party and a bright character in both ile evlendi, Hanedan’a damat oldu (1914). I. Dünya Savaşı the military and political arena. He married Naciye Sultan, sırasında Harbiye Nazırı ve Başkumandan Vekili’ydi. granddaughter of Sultan Abdülmecid and thus became the Türk-Alman ittifakının mimarı olarak algılanan Enver son-in-law to the Ottoman Dynasty (1914). He was the Minister Paşa, yenilginin ardından ülkeyi savaşa ittiği suçlamasıyla of War and Deputy Chief Commander during World War I. idama mahkûm edildi, rütbeleri alındı. Türk devletlerini Considered to be the architect of the Turkish-German alliance, birleştirme idealiyle Rus topraklarına kaçtı. -

Cumhuriyet Öncesinde Türk Kadını

T.C. BAŞBAKANLIK AİLE ARAŞTIRMA KURUMU BAŞKANLIĞI Cumhuriyet Öncesinde TÜRK KADINI (1839-1923) İKİNCİ BASKI Şefika KURNAZ Ankara 1991 T.C. BAŞBAKANLIK AİLE ARAŞTIRMA KURUMU BAŞKANLIĞI YAYINLARI Genel Yayın No: 4 Seri : Bilim Serisi ISBN : 975-19-0285-1 Redaksiyon: Dr. C. Doğan, E. Özensel, S. Güneş. A R. Kalaycı, E Özdemir Dizgi : Reyhan Grafik Baskı : Öz-EI Matbaası SUNUŞ 1980 ortalarından itibaren ülkemizde kadın orijinli hareket ve yaklaşımların büyük bir mesafe katettiği biliniyor. Bunda Birleşmiş Milletler gibi bazı uluslararası kuruluşlarla vakıfların sağladığı kaynak ve motivasyonların büyük bir payı bulunuyor. Bu arada iki ku- tuplu bir dünyadan tek kutuplu bir dünyaya geçerken, sosyalizmin bıraktığı büyük boşlukta kadın hakları ve "feminizm"in, neredeyse bir ideoloji gibi sunu- lup algılanmasının da bundaki payı büyük. Kadın konusundaki yaklaşımların sansasyonal boyutlar taşıması, her ne kadar harekete bir ivme kazandırmak amacından ileri gelse de, sonuçta, toplum- sal katılımı geciktiren fonksiyonlar ürettiği de bir gerçek. Gelişmeye ve değişime karşı aşırı ön yargıları bulunmayan Türk toplumunun, aceleci ve yaptırımcı tavırları bir "şiddet" unsuru olarak algıladığını da burada kaydetmek gerekiyor. Bu yaklaşımların içine düştüğü bir durum da, kadını mensubu olduğu sosyal üniteden, yani aileden soyutlayarak ele almaya kalkışmasıdır. Kadını, o toplu- mun temelini oluşturan aileden bağımsızlaştırarak ele almak, toplumsal gerçeklikleri veya sosyal kurumları yok farzetmek anlamına gelebilir. Kadın, erkek ve çocuğun kendi bireyi ile sınırlandırılabilecek tarafının yanı sıra, onların, ailenin bütünlüğü içinde üstlendiği bir takım rol ve statülerin de bulun- duğunu biliyoruz. Halbuki sosyal kurumların değişmesi, bizim arzularımızın hilâfına daha uzun zamanlara ihtiyaç gösterebilir. Daha ötede bu problemi üretim biçimlerinin, ailelerin hayat tarzının geçireceği büyük dönüşümlerden bağımsız düşünmek de mümkün değildir. -

Osmanli Hanedaninin Geri Dönen Ilk Üyeleri (1924‐1951)

TARİHİN PEŞİNDE THE PURSUIT OF HISTORY ‐ULUSLARARASI TARİH ve SOSYAL ARAŞTIRMALAR DERGİSİ‐ ‐INTERNATIONAL PERIODICAL FOR HISTORY AND SOCIAL RESEARCH‐ Yıl: 2014, Sayı: 12 Year: 2014, Issue: 12 Sayfa: 83‐117 Page: 83‐117 SÜRGÜNDEN VATANA: OSMANLI HANEDANININ GERİ DÖNEN İLK ÜYELERİ (1924‐1951) Cahide SINMAZ SÖNMEZ* Özet 3 Mart 1924 tarihinde Halifeliğin kaldırılmasıyla beraber Osmanlı Hanedanı üyeleri de süresiz bir şekilde sınır dışı edilmişlerdir. Sürgüne giden hanedan mensuplarının pek çoğu bu durumun kısa sürede son bulacağı ümidiyle ülkeyi terk etmişler, ancak dönüş süreci beklenenden uzun sürmüştür. Kadınlar 16 Haziran 1952 tarihinde çıkarılan özel bir kanunla dönüş izni alırken, erkekler ise 15 Mayıs 1974 tarihli Genel Af yasasının 8. mad‐ desiyle geri dönebilmişlerdir. Ancak, 1952 yılına kadar yasağın devam ediyor olmasına rağmen bazı istisnai uygulamalar yaşanmıştır. Bu araştırmanın konusunu da 3 Mart 1924 tarihinden 16 Haziran 1952 tarihine kadar geçen süre içerisinde yaşanan istisnai örnekler oluşturmaktadır. Anahtar Kelimeler Halifeliğin Kaldırılışı, Osmanlı Hanedanı, Sürgün, Geri Dönüş, Pasaport Kanunu FROM EXILE TO THE HOMELAND: THE FIRST RETURNING MEMBERS OF THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY (1924‐1951) Abstract Members of the Ottoman Dynasty were sent into an indefinite exile after the abolishment of the Caliphate on March 3, 1924. A great majority of the dynasty members left the country with the hope that deportation would end soon, but the process of returning back to the country has lasted longer than expected. Female members of the dynasty have acquired the right to return with a special law issued on June 16, 1952 while the male members of the dynasty were able to return with the 8th article of the General Amnesty issued on May 15, 1974. -

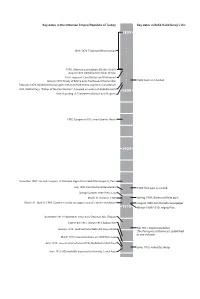

Key Dates in Refik Halid Karay's Life

Philliou - Timeline 5th proof Bill Nelson 6/9/20 Key dates in the Ottoman Empire/Republic of Turkey Key dates in Rek Halid Karay’s life: Key dates in the Ottoman Empire/Republic of Turkey Key dates in Rek Halid Karay’s life: 1914: Marries Nâzime in Sinop while in exile 1839 August 1914: Ottoman Empire enters period of “Active Neutrality” 1915 November 1914: Ottoman Empire enters World War One in earnest July 1915: transferred to Çorum Spring 1915–1916: Armenian Genocide August 1916: transferred to Ankara 1839–1876: Tanzimat Reform period October 1916: transferred to Bilecik October 30,1918: Ottoman defeat in World War One; Armistice of Mudros January 1918: returns to Istanbul 1876: Ottoman constitution (Kânûn-i Esâsî) January 1919: Paris Peace Conference convenes August 1876: Abdülhamid II takes throne May 1919: Greek invasion of Izmir Fall 1918: rst novel: The True Face of Istanbul 1878: suspends Constitution and Parliament (İstanbul’un İç Yüzü) January 1878: Treaty of Edirne ends the Russo-Ottoman War 1888: born in Istanbul June–September 1919: mobilization of resistance forces under leadership of Mustafa Kemal [Atatürk] April–October 1919: Post Telegraph and Telephone February 1878: Abülhamid II prorogues Ottoman Parliament, suspends Constitution 1920: Last Ottoman Parliament passes National Pact [Misak-ı Millî] General Directorate, rst tenure 1884: Midhat Paşa, “Father of the Constitution” strangled on orders of Abdülhamid II 1920 1900 March 16, 1920: British occupation of Istanbul becomes ocial March–April 1920: PTT General Directorate, -

Indirmenin, Ihtiyaç Sahibinin Onurunu Korumanın, Dünyanın Nere- Sinde Bir Mazlum Varsa Yarasını Sarmanın, Gözyaşını Silmenin Mücadelesini Veriyoruz

TÜRK KIZILAYI TARİH DİZİSİ Türk Kızılayı, Türk Halkının dünyaya uzattığı merhamet eli olarak yak- laşık bir buçuk asırdır ulvi bir görevi büyük bir özveri ile yerine getirmekte- dir. Kurulduğu 1868 yılından bu yana halkımızın ve özellikle yakın coğrafi komşularımızın başına gelen her türlü felâkette görev alan ve tarihe tanıklık eden Türk Kızılayı, maalesef bu tanıklığını ilgililere ve yeni nesillere taşıya- cak çalışmaları ihmal etmiştir. Elbetteki yapılan her türlü yardım çalışmasının yazışmaları Türk Kızılayı arşivlerindeki yerlerini almıştır. Ancak, bu çalışmaları arşivlerden kurtarmak ve yardımlaşma duygusunun cisimleşmiş hali olan Türk Kızılayı’nın anlata- cak eserleri haline getirmek bizler için tarihi bir görev olmuştur. Bu görevi yerine getirebilmek amacıyla bir çalışma başlatılmıştır. Türk Kızılayı Kitaplığı olarak adlandırılan bu çalışmada ilk olarak Kızılayımızın tarihine ışık tutacak belgelerin kitaplaştırılması hedeflenmiştir. Zaman için- de ise güncel çalışmalar kitaplaştırılacaktır. Türk Kızılayı, tarihi tanıklığıyla dünün daha iyi anlaşılmasına, bugünün bu bilgiler ışığında değerlendirilme- sine ve geleceği planlarken ulusumuzun geçirdiği acılı sürecin bilinmesinde büyük yararlar görmektedir. Türk Kızılayı Kitaplığı serisinin oluşumuna fikirleri ve emekleriyle destek veren herkese teşekkürü bir borç biliriz. Padişah'ın Himayesinde OSMANLI KIZILAY CEMİYETİ 1911-1913 YILLIĞI Hazırlayanlar Yrd. Doç. Dr. Ahmet Zeki İZGÖER • Msc. Ramazan TUĞ Koordinatörler Belgin Duruyürek Şahin Cengiz Kapak Fotoğrafı Osmanlı Kızılay Cemiyeti -

ROMA Ve BİZANS ETÜDLER VE SİSTEMATİK ESERLER

ROMA ve BİZANS ETÜDLER VE SİSTEMATİK ESERLER ALBERT, GOTTFRIED: Die Prinzeninsel Antigoni und der Aidos- Berg. Konstantinopel, O. Keil, [1891]. s. 24-51. (15.5x22). “Mitteilungen des Deutschen Excursions Clubs, Heft III”. [I.RB/E-367] ANGOLD, MICHAEL: Church and society in Byzantium under the Comneni, 1081-1261. Cambridge, Cambridge University, 1995. XVI+604 s. (15.5x23.5). [I.RB/E-388] BALARD, MİCHEL - DUCELLIER, ALAIN (Der.) : Konstantinopolis 1054-1261. Hırıstiyanlığın başı, Latinlerin avı, Yunan başkenti. İstanbul, İletişim, 2002. 256 s. (16x23). “İletişim Yay.: 842 - Dünya Şehirleri Dizisi: 6”. [I.RB/E-405] BARSANTI, CLAUDIA : Constantinopoli e l’Egeo nei primi decenni del XV secolo: la testimonianza di Cristoforo Buondelmonti. s. 83-254. (21x29). Roma, Rivista dell’Istituto Nazionale d’Archeologia e Storia dell’arte, 56 (III. Serie, XXIV), 2001’den. Fotokopidir. [I.RB/E-407] BARTUSIS, MARK C.: The late Byzantine army: arms and society, 1204-1453. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992. XVII+438 s. (15x23) resim. “The Middle Ages Series”. [I.RB/E-408] 1 BASSETT, SARAH GUBERTI : Historiae custos: Sculpture and tradition in the Baths of Zeuxippos. s. 491-506. (21x29.5) plan, resim. American Journal of Archaeology Volume, 100, No: 3/1996’dan. Fotokopidir. [I.RB/E-391] BELGE, MURAT : Bizans mirası. Foto.: Şemsi Güner. s. 86-102. (22x30) resim. Atlas dergisi, 1994, (Sayı 17)’de. [I.RB/E-392] BOOJAMRA, JOHN LAWRENCE : Church reform in the late Byzantine Empire. A study for the patriarchate of Athanasios of Constantinople. Thessaloniki, Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1983. 239 s. (18x25). “Analekta Vlatadon, 35”. [I.RB/E-362] BRADFORD, ERNLE : The great betrayal. -

The Russian Intervention

INSTITUTE PROCEEDINGS The extended war on the Eastern Front, 1918-1925: the Russian Intervention A paper based on a presentation to the Institute on 27 November 2018 by Bryce M. Fraser Military Historian Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, New South Wales1 Conflict in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and the Middle East, over issues which plagued the region at the end of the Great War, continues to this day. Although considered insignificant by some historians and overshadowed by the gigantic scale of warfare during the two World Wars, the Russian Intervention was substantial and Australians played a significant role in it, two winning the Victoria Cross and one the Distinguished Service Order. Key words: Australia; Russia; Russian Intervention, 1918-1919; North Russian Expeditionary Force; North Russian Relief Force; Murmansk; Archangel; Siberian Intervention; South Russia; Transcaucasus Intervention; Dunsterforce; Lionel Dunsterville; Stanley Savige. The late historian Eric Hobsbawm in The Age of precarious at the end of 1917. In October, the inconclusive Extremes (Hobsbawm 1994) coined the term ‘the short battle of Passchendaele had a month to run. In the Atlantic, twentieth century’ to describe the period of conflict in despite the introduction of convoys, submarine warfare Europe from 1914 to the collapse of the Union of Soviet was still sinking 300,000 tons of shipping per month. In Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1991, in contrast to the Palestine, the Third Battle of Gaza was just underway. The customary view that fighting in the Great War ended with only good news would be the Allied capture of Jerusalem the armistice of 11 November 1918 on the Western Front. -

Hilâl-I Ahmer Hanimlar Merkezinin Kuruluşu Ve

HİLÂL-İ AHMER HANIMLAR MERKEZİ’NİN KURULUŞU VE FAALİYETLERİ (1877-1923) Muzaffer TEPEKAYA* - Leyla KAPLAN* ÖZET Osmanlı Hilâl-i Ahmer Cemiyeti bünyesinde 20 Mart 1912 tarihinde “Osmanlı Hilâl-i Ahmer Hanımlar Merkezi” kurulmuştur. Kurulan bu teşkilatla kadınlar etkili bir şekilde Hilâl-i Ahmer faaliyetlerine katılmışlardır. Kuruluşundan itibaren cephede savaşan askerlere, yaralı ve hastalara, kimsesizlere ve bakıma muhtaç olanlara, şehit ve asker ailelerine göçmenlere, esirlere yardım eden Hilal-i Ahmer Hanımlar Merkezi, bu faaliyetlerini bağış kampanyalarının yanı sıra, aşhane, çayhane, hastane, dispanser, sanat evi, atölyeler, nekahet-hane, gibi kuruluşlar aracılığıyla gerçekleştirmektedir. Osmanlı Devleti’ni sona erdiren 24 Temmuz 1923 Lozan siyasi antlaşmasının imzalanmasından sonra yeni kurulan Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Devleti’nde de faaliyetlerine devam eden dernek Yunanistan’la yapılan Türkiye Rum mübadelesinde önemli görevler üstlenmiştir. Mübadele ile gelen göçmenlerin sağlık, giyim ihtiyaçlarının karşılanması, yerleşecekleri yerlere nakilleri, hastalarının bakımı ve sağlık bilgilerinin verilmesinde başarıyla görev yapmıştır. Cumhuriyetin ilânından sonra “Cumhuriyet Vatandaşı” kimliği oluşturmak için yapılan çalışmalara katılan ve yenilikleri Türk toplumuna benimsetmede önemli görevler yerine getiren Hilâl-i Ahmer Kadınları “Cumhuriyet Kadını” kimliğini benimseterek bunun yaygınlaştırılmasında başarıyla çalışmıştır. Yardım faaliyetleriyle birlikte peş peşe gerçekleştirilen inkılapları destekleyen derneğin çalışmalarına dönemin gazetelerinde -

British Foreign Policy in Azerbaijan, 1918-1920 Afgan Akhmedov A

British Foreign Policy in Azerbaijan, 1918-1920 Afgan Akhmedov A thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Lancaster March 2018 Afgan Akhmedov 2018 2 Abstract This thesis examines Anglo-Russian rivalry in Transcaucasia in general - and Azerbaijan in particular - focusing on the years 1918-1920. The first part of the thesis provides a general review of the history of the Great Game - the geopolitical rivalry between the British and Russian Empires fought in the remote areas of central Asia - before going on to examine the growing investment by British firms in the oil industry of Baku. It also discusses how the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907 changed the texture of Anglo- Russian relations without resolving the tensions altogether, which lasted until the February Revolution of 1917, despite the wartime alliance between Britain and Russia. The thesis then goes on to examine British policy towards Transcaucasia after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. The thesis argues that the political turmoil in Russia provided the British government with an opportunity to exert greater political control over the south of the country, securing its access to oil and control of the Caspian Sea region, thereby reducing any potential threat to India. The allied victory in the First World War, and the weakening of Turkey in particular, meant that British policy in central Asia after November 1918 increasingly focused on advancing British economic and strategic interests in the area. Although the British government did not seek to exert direct long-term political control over Azerbaijan, its policy in 1919 was designed both to support the local government in Baku against possible Bolshevik attack, whilst simultaneously exerting control over Baku oil. -

Harun Açba KADINEFENDİLER {1839-1924} KADINEFENDİLER {1839-1924}

SON DÖNEM OSMANLI PADİŞAH EŞLERİ Harun Açba KADINEFENDİLER {1839-1924} KADINEFENDİLER {1839-1924} Harun Açba PROFİL O Hanın Açba O PROFİL YAYINCILIK Yazar/Harun Açba Eserin Adı / Kadirdendiler Genel Koordinatör /'Münir Üstün Genel Yayın Yönetmeni / Cem Küçük Redaksiyon I Elif Avcı Kapak Tasarım/ Yunus Karaasian İç Tasarım I Adem Şenel Baskı-Cilll Kitap Matbaası Davulpap Cad. fminraj Ka/ım Dinçol San. Sil. No.81/21 Topkapı -İstanbul Tel: 0212 567 .10 8-1 1. BASKI KASIM 2007 978-975-996-109-1 PROFİL : 65 İNCELEME-ARAŞTIRMA :07 PROFİL YAYINCILIK Çatalçcsme Sk. Meriçli Apt. No: 52 K.3 Cagaloglu - İSTANBUL www.profilkilap.com / [email protected] Tel. 0212. 514 45 11 Faks. 0212. 514 45 12 Profil Yayıncılık Maviağaç Küllür Sanat Yayıncılık Tic.Ltd.Şti rnarkasıdır. ı © Bu kitabın Türkçe yayın hakları Harun Açba ve Prolil Yayıncılık'a aittir. Yazarın ve yayıncının izni olmadan herhangi bir formda yayınlanamaz. kopyalanamaz ve çoğaltılamaz. Ancak kaynak gösterilerek alınlı yapılabilir. İÇİNDEKİLER Bölüm 1 Kafkasya Hanedanları / 9 Saray Protokolü /13 Bölüm 2 Sultan I. Abdülmecid Han Ailesi / 17 (1839-18611 Sultan Abdülaziz Han Ailesi / 81 (1861-1876) Sultan V. Murad Han Ailesi / 96 (1876) Sultan II. Abdülhamid Han Ailesi / 117 (1876-1909) Sultan V. Mehmed Reşad Han Ailesi / 161 (1909-1918) Sultan VI. Mehmed Vahideddin Han Ailesi / 180 (1918-1922) Halife II. Abdülmecid Efendi Ailesi / 207 (1922-1924) Bibliyografya / 217 Teşekkkürname / 218 Bu kitabı aileme ithaf ediyorum. BÖLÜM 1 KAFKASYA HANEDANLARI smanlı Sarayı'na alınan kızların (19. yy. özellikle) Çerkeş olduğu biliniyor. Sultan Abdülmecid Han'a kadar tâbi Okalınan köle, yani cariye ticareti üzerine kurulan Os manlı haremi Abdülmecid Han'dan sonra değişikliğe uğramıştır.