States and Castes in Colonial India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Raja of Princely State Fled to the Mountain to Escape Sikh Army's

1 1. Raja of princely state fled to the mountain to escape Sikh army’s attack around 1840 AD? a) Mandi b) Suket c) kullu d) kehlur 2. Which raja of Nurpur princely State built the Taragarh Fort in the territory of Chamba state? a) Jagat Singh b) Rajrup Singh c) Suraj Mal d) Bir Singh 3. At which place in the proposed H.P judicial Legal Academy being set up by the H.P. Govt.? a) Ghandal Near Shimla b) Tara Devi near Shimla c) Saproon near Shimla d) Kothipura near Bilaspur 4. Which of the following Morarian are situated at keylong, the headquarter of Lahul-Spiti districts of H.P.? CHANDIGARH: SCO: 72-73, 1st Floor, Sector-15D, Chandigarh, 160015 SHIMLA: Shushant Bhavan, Near Co-operative Bank, Chhota Shimla 2 a) Khardong b) Shashpur c) tayul d) All of these 5. What is the approximately altitude of Rohtang Pass which in gateway to Lahul and Spiti? a) 11000 ft b) 13050 ft c) 14665 ft d) 14875 ft 6. Chamba princely state possessed more than 150 Copper plate tltle deads approximately how many of them belong to pre-Mohammedan period? a) Zero b) Two c) five d) seven 7. Which section of Gaddis of H.P claim that their ancestors fled from Lahore to escape persecution during the early Mohammedan invasion? a) Rajput Gaddis b) Braham in Gaddis CHANDIGARH: SCO: 72-73, 1st Floor, Sector-15D, Chandigarh, 160015 SHIMLA: Shushant Bhavan, Near Co-operative Bank, Chhota Shimla 3 c) Khatri Gaddis d) None of these 8. Which of the following sub-castes accepts of firing in the name of dead by performing the death rites? a) Bhat b) Khatik c) Acharaj d) Turi’s 9. -

OBITUARY Bravo Raja Sahib (1923-2010)

OBITUARY Bravo Raja Sahib (1923-2010) On Friday May 7th 2010 Raja Mumtaz Quli Khan passed away peacefully at his home in Lahore. Physically debilitated but mentally active and alert till his death. His death is most acutely felt by his family but poignantly experienced by all with whom he was associated as he was deeply admired by his students, patients, colleagues and friends. In him we have lost a giant in ophthalmology and the father of Ophthalmological Society of Pakistan. His sad demise marks the end of an era. It is difficult to adequately document and narrate the characteristics and qualities which made him such a dedicated teacher, organizer and most of all a great friend known as Raja Sahib to all of us. He was an inspiration to his colleagues, to his students and children of his students who ultimately became his students. Raja Sahib was born in a wealthy, land owning family in a remote village of Gadari near Jehlum on July 16th 1923. He went to a local school which was a few miles from his village and he used to walk to school as there were no roads in that area, although with his personal effort and influence he got a road built but many years after leaving school when he had become Raja Sahib. Did metric in 1938 and B.Sc. form F.C College Lahore in 1943 and joined Galancy Medical College Amritser (Pre- partition) and after creation of Pakistan joined K.E. Medical College Lahore. After completing his MBBS in 1948 from KEMC he did his house job with Prof. -

Libraries in West Malaysia and Singapore; a Short History

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 059 722 LI 003 461 AUTHOR Tee Edward Lim Huck TITLE Lib aries in West Malaysia and Slngap- e; A Sh History. INSTITUTION Malaya Univ., Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia). PUB DATE 70 NOTE 169p.;(210 References) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Foreign Countries; History; *Libraries; Library Planning; *Library Services; Library Surveys IDENTIFIERS *Library Development; Singapore; West Malaysia ABSTRACT An attempt is made to trace the history of every major library in Malay and Singapore. Social and recreational club libraries are not included, and school libraries are not extensively covered. Although it is possible to trace the history of Malaysia's libraries back to the first millenium of the Christian era, there are few written records pre-dating World War II. The lack of documentation on the early periods of library history creates an emphasis on developments in the modern period. This is not out of order since it is only recently that libraries in West Malaysia and Singapore have been recognized as one of the important media of mass education. Lack of funds, failure to recognize the importance of libraries, and problems caused by the federal structure of gc,vernment are blamed for this delay in development. Hinderances to future development are the lack of trained librarians, problems of having to provide material in several different languages, and the lack of national bibliographies, union catalogs and lists of serials. (SJ) (NJ (NJ LIBR ARIES IN WEST MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE f=t a short history Edward Lirn Huck Tee B.A.HONS (MALAYA), F.L.A. -

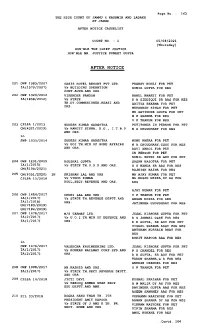

Causelist Dated:- 05-08-2021

Page No. : 163 THE HIGH COURT OF JAMMU & KASHMIR AND LADAKH AT JAMMU AFTER NOTICE CAUSELIST COURT NO. : 1 05/08/2021 [Thursday] HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PUNEET GUPTA AFTER NOTICE 201 OWP 1083/2007 OASIS HOTEL RESORT PVT.LTD. PRANAV KOHLI FOR PET IA(1570/2007) Vs BUILDING OPERATION SONIA GUPTA FOR RES CONT.AUTH.AND ORS. 202 OWP 1329/2012 VIRENDER PANDOH RAHUL BHARTI FOR PET IA(1858/2012) Vs STATE H A SIDDIQUI SR AAG FOR RES TH.DY.COMMSSIONER,REASI AND ADITYA SHARMA FOR PET ORS. MEHARBAN SINGH FOR PET MR.SATINDER GUOTA FOR PET M P SHARMA FOR RES O P THAKUR FOR RES 203 CPLPA 1/2013 SUDESH KUMAR GARGOTRA PETITONER IN PERSON FOR PET CM(4321/2019) Vs RANJIT SINHA, D.G., I.T.B.P N A CHOUDHARY FOR RES AND ORS. in SWP 1035/2014 SUDESH KUMAR GARGOTRA NONU KHERA FOR PET Vs UOI TH.MIN.OF HOME AFFAIRS N A CHOUDHARY,CGSC FOR RES AND ORS. RAVI ABROL FOR PET IN PERSON FOR PET SUNIL SETHI SR ADV FOR PET 204 OWP 1231/2015 KOUSHAL GUPTA GAGAN BASOTRA FOR PET IA(1/2015) Vs STATE TH.U.D.D.AND ORS. S S NANDA SR AAG FOR RES CM(5108/2021) RAJNISH RAINA FOR RES 205 CM(6351/2020) IN KRISHAN LAL AND ORS MR.AJAY KUMAR FOR PET CPLPA 15/2016 Vs VINOD KUMAR MR.EHSAN MIRZA,DY.AG FOR KOUL,SECY.REVENUE AND ORS. RES AJAY KUMAR FOR PET 206 OWP 1454/2017 CHUNI LAL AND ORS. -

Castes and Caste Relationships

Chapter 4 Castes and Caste Relationships Introduction In order to understand the agrarian system in any Indian local community it is necessary to understand the workings of the caste system, since caste patterns much social and economic behaviour. The major responses to the uncertain environment of western Rajasthan involve utilising a wide variety of resources, either by spreading risks within the agro-pastoral economy, by moving into other physical regions (through nomadism) or by tapping in to the national economy, through civil service, military service or other employment. In this chapter I aim to show how tapping in to diverse resource levels can be facilitated by some aspects of caste organisation. To a certain extent members of different castes have different strategies consonant with their economic status and with organisational features of their caste. One aspect of this is that the higher castes, which constitute an upper class at the village level, are able to utilise alternative resources more easily than the lower castes, because the options are more restricted for those castes which own little land. This aspect will be raised in this chapter and developed later. I wish to emphasise that the use of the term 'class' in this context refers to a local level class structure defined in terms of economic criteria (essentially land ownership). All of the people in Hinganiya, and most of the people throughout the village cluster, would rank very low in a class system defined nationally or even on a district basis. While the differences loom large on a local level, they are relatively minor in the wider context. -

Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in a Subregion of Far Western Nepal Walter F

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 4 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin, Monsoon Article 7 1984 1984 Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in A Subregion of Far Western Nepal Walter F. Winkler Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Winkler, Walter F. (1984) "Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in A Subregion of Far Western Nepal," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 4: No. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol4/iss2/7 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ... ORAL HISTORY AND THE EVOLUTION OF THAKUR! POLITICAL AUTHORITY IN A SUBREGION OF FAR WESTERN NEPAL Walter F. Winkler Prologue John Hitchcock in an article published in 1974 discussed the evolution of caste organization in Nepal in light of Tucci's investigations of the Malia Kingdom of Western Nepal. My dissertation research, of which the following material is a part, was an outgrowth of questions John had raised on this subject. At first glance the material written in 1978 may appear removed fr om the interests of a management development specialist in a contemporary Dallas high technology company. At closer inspection, however, its central themes - the legitimization of hierarchical relationships, the "her o" as an organizational symbol, and th~ impact of local culture on organizational function and design - are issues that are relevant to industrial as well as caste organization. -

Download Full Text

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research ISSN: 2455-8834 Volume:04, Issue:01 "January 2019" POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE BRITISH AND THE MANIPURI RESPONSES TO IT IN 1891 WAR Yumkhaibam Shyam Singh Associate Professor, Department of History Imphal College, Imphal, India ABSTRACT The kingdom of Manipur, now a state of India, neighbouring with Burma was occupied by the Burmese in 1819. The ruling family of Manipur, therefore, took shelter in the kingdom of Cachar (now in Assam) which shared border with British India. As the Burmese also occupied the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam and the Cachar Kingdom threatening the British India, the latter declared war against Burma in 1824. The Manipuris, under Gambhir Singh, agreed terms with the British and fought the war on the latter’s side. The British also established the Manipur Levy to wage the war and defend against the Burmese aggression thereafter. In the war (1824-1826), the Burmese were defeated and the kingdom of Manipur was re-established. But the British, conceptualizing political economy, ceded the Kabaw Valley of Manipur to Burma. This delicate issue, coupled with other haughty British acts towards Manipur, precipitated to the Anglo- Manipur War of 1891. In the beginning of the conflict when the British attacked the Manipuris on 24th March, 1891, the latter defeated them resulting in the killing of many British Officers. But on April 4, 1891, the Manipuris released 51 Hindustani/Gurkha sepoys of the British Army who were war prisoners then giving Rupees five each. Another important feature of the war was the involvement of almost all the major communities of Manipur showing their oneness against the colonial British Government. -

Pahari Paintings from the Eva and Konrad Seitz Collection

PAHARI PAINTINGS FROM THE EVA AND KONRAD SEITZ COLLECTION francesca galloway ww.francescagalloway.com 1 2 Pahari paintings, meaning paintings from the hills, come from the in Jammu, and Chamba had returned to their non-naturalistic Rajput roots mountainous regions of northern India once known as the Punjab Hills but and were illustrating traditional Hindu texts such as the Ramayana (cat. 2), the which now form the present day states of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Rasamanjari and Ragamalas (cat. 1) in brilliantly assured fashion, dependent Pradesh and Uttarakhand. They include some of the most brilliant as well as again on line and colour with their figures set against conceptual renderings the most lyrically beautiful of all Indian painting styles. of architecture and landscape. Such a style had spread throughout most of the Pahari region in the early 18th century. In the 17th and 18th centuries this area was divided into over 30 kingdoms, some of moderate size, but others very small. The kingdoms were established in Although much of the hill region formed strongholds for the worship of Shiva the fertile valleys of the rivers that eventually flowed into the plains – the Ravi, and the Devi, and paintings and manuscripts reflected this (e.g. cats. 12, 13), the Beas, Sutlej, and the Jumna and Ganges and their tributaries – and divided spread of Vaishnavism and, especially the worship of Krishna, induced patrons from each other by high mountains. The Himalayas to the north-east formed to commission illustrated versions of Vaishnava texts, such as the Bhagavata the almost impenetrable barrier between these little kingdoms and Tibet. -

Changing Caste Relations and Emerging Contestations in Punjab

CHANGING CASTE RELATIONS AND EMERGING CONTESTATIONS IN PUNJAB PARAMJIT S. JUDGE When scholars and political leaders characterised Indian society as unity in diversity, there were simultaneous efforts in imagining India as a civilisational unity also. The consequences of this ‘imagination’ are before us in the form of the emergence of religious nationalism that ultimately culminated into the partition of the country. Why have I started my discussion with the issue of religious nationalism and partition? The reason is simple. Once we assume that a society like India could be characterised in terms of one caste hierarchical system, we are essentially constructing the discourse of dominant Hindu civilisational unity. Unlike class and gender hierarchies which are exist on economic and sexual bases respectively, all castes cannot be aggregated and arranged in hierarchy along one axis. Any attempt at doing so would amount to the construction of India as essentially the Hindu India. Added to this issue is the second dimension of hierarchy, which could be seen by separating Varna from caste. Srinivas (1977) points out that Varna is fixed, whereas caste is dynamic. Numerous castes comprise each Varna, the exception to which is the Brahmin caste whose caste differences remain within the caste and are unknown to others. We hardly know how to distinguish among different castes of Brahmins, because there is complete absence of knowledge about various castes among them. On the other hand, there is detailed information available about all the scheduled castes and backward classes. In other words, knowledge about castes and their place in the stratification system is pre- determined by the enumerating agency. -

COLONIAL INTERVENTION and INDIRECT RULE in PRINCELY JAMMU and KASHMIR Dr Anita Devi Research Scholar, Department of History, AFFILIATION: University of Jammu

COLONIAL INTERVENTION AND INDIRECT RULE IN PRINCELY JAMMU AND KASHMIR Dr Anita Devi Research Scholar, Department of History, AFFILIATION: University of Jammu. EMAIL ID: [email protected], CONTACT NO: 7006530645 Abstract This paper tries to throw light on the intervention of British colonial power in Indian states during nineteenth and twentieth century and main focus of the work is on princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, which was one of the largest princely states in India along with Hyderabad and Mysore. The paper unreveals the motive and benefits behind indirect annexation and also obligations of princes to accept paramountcy. The indirect rule observed different degrees of interference and it was supposed to correct abuses in so called backward native states. Key Words: Paramountcy, Princely, Colonial, Indirect rule, Intervention, Native. Introduction After 1858, British abandoned their earlier policies of “ring fence” (1765- 1818) and “subordinate isolation” (1818-1858) and adopted new policy which laid stress on “non-annexation with the right of intervention” and it remained functional from 1858 till 1947. These un-annexed areas came to be known as Princely states. By intervention it means that government had right to intervene in the internal affairs of native states and set right administrative abuses. Michael Fisher opined that by this arrangement the colonial power was able to gain control over nominally sovereign states through a single British resident or political agent or just by giving advices to local princes.1 Indirect rule refers to the system of administration where states were directly ruled by native princes under the paramount power. -

1 Hyderabad Municipal Survey Index to CHADARGHAT and RESIDENCY AREA

1 Hyderabad Municipal Survey Index to CHADARGHAT AND RESIDENCY AREA (Leonard Munn 1911-13). Area 9, 1- 64 (missing 13, 17, 21, 32, 37, 38, 39, 40, 45, 47, 53, 56, 60, 61, 62, 63) Compiled by Arvin Mathur and Karen Leonard, 2015 Details below, names and features on each map; [ ] =title on index; QS=Qutb Shahi 1 [Khusrau Manzil] Nawab Zafar Jang; Nawab Zafar Jang Br. (gdn); Dewal; Dewal; Dewal; Dewal; Habibnagar Road; Bihari Lal (gdn); Bihari Lal Dewal; Dewal Hanuman; Darmsala; Samadh; Baoli; Bagh Hanuman (gdn); Regtl. Stores; Tennis court; Second Infantry Guard Street; Khusrau Manzil; Raja Tej Rao; Mukarrab Jang Tank Street; Quarter Guard; Bell of Arms Right Wing; Bell of Arms Left Wing; Orderly Room 2 [A.C.G. Barracks] Masan (gdn); Bihari Lal (gdn); Baoli; Nawab Akbar Jang Br. (gdn); Hockey Ground; Stables; Stables; Quarter Guard; Baoli; Magazine; Tennis Court; Tennis Court 3 [Town Hall/Public Gardens] Town Hall; Animals; Baoli; Office of the Superintendent; Stores; Tennis Court; Tennis Court; Brigade Office Lane; Police station; Muhammad Hassan-ud-Din Khan; Nala; Clock Tower; Tennis Court; Public Gardens Gate Road 4 [Fateh Maidan] Nawab Hussain Dost Khan; baoli; Brigade Office Lane; Moti Lal Sahu (gdn); Dewal; Brigade Office; Divisional Office; Band School; Officers’ Mess H. H. The Nizam’s Regular Troops; Bashir Bagh Road; Fateh Maidan; Police Station 5 [ ] Takya; Fakhr-ul-Mulk Br. (gdn); Baoli; Masan; Baoli; Baoli; Reservoir; Rai Murli Dhar Br.; Baoli; Bishangir Gosa-in; baoli; Dewal Mata; Reservoir; baoli; reservoir; reservoir 6 [Phul Bagh] Rai Murli Dhar Br.; Baoli; Dhobi Ghat; reservoir; Ramkaran Sahu (gdn); Masan; Baoli; Baoli 7 [Narayangura] Dhobi Ghat; reservoir; baoli; baoli; Karim-ud-din Sahib (gdn) 8 [Distillery] Baoli; Ghiyas-ud-din Sahib; Nala Basharat; Kakku Raja; Ghiyas-ud-din Sahib (gdn); Bhagwan Das (gdn); Askar Jang Br. -

Diversity of Governance & India's Struggle for Integration

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 11, Ver. 7 (November. 2017) PP 92-95 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Diversity Of Governance & India’s Struggle For Integration Dr Iti Roychowdhury Prof and Head, Amity School of Languages Amity University MP [email protected] ABSTRACT: Freedom for India had different connotations for different Indians. The Indian Independence Act of 1947 freed the country from the British yolk and gave birth to a new nation : Pakistan. Hence for many Indians the Act of 1947 represented freedom, independence, sovereignty. However the states of India that were governed by native rulers functioned under a different paradigm. The departure of the British created a conundrum of identity, governance, sovereignty for India‟s 600 odd Princely States. The present paper explores how these 600PricelyStates were governed, what were the aspirations of the peoples therein and how a climate was created for the states to become integrated with the Indian Union. Key Words: British India, Freedom Struggle, Integration, People‟s Movements, Princely States ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 06-11-2017 Date of acceptance: 17-11-2017 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. INTRODUCTION The British conquest of India was piecemeal. Some Indian states were annexed outright through military conquests, others through the Doctrine of Lapse, still others on the pretext of maladministration while the majority of Indian Rajas signed the Subsidiary Alliance whereby a British Resident and a subsidiary force got stationed at the Court and the native prince paid a fixed sum to the British. Thereafter the Native ruler was free to rule his territory as he saw fit.