Pahari Paintings from the Eva and Konrad Seitz Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

1. Raja of Princely State Fled to the Mountain to Escape Sikh Army's

1 1. Raja of princely state fled to the mountain to escape Sikh army’s attack around 1840 AD? a) Mandi b) Suket c) kullu d) kehlur 2. Which raja of Nurpur princely State built the Taragarh Fort in the territory of Chamba state? a) Jagat Singh b) Rajrup Singh c) Suraj Mal d) Bir Singh 3. At which place in the proposed H.P judicial Legal Academy being set up by the H.P. Govt.? a) Ghandal Near Shimla b) Tara Devi near Shimla c) Saproon near Shimla d) Kothipura near Bilaspur 4. Which of the following Morarian are situated at keylong, the headquarter of Lahul-Spiti districts of H.P.? CHANDIGARH: SCO: 72-73, 1st Floor, Sector-15D, Chandigarh, 160015 SHIMLA: Shushant Bhavan, Near Co-operative Bank, Chhota Shimla 2 a) Khardong b) Shashpur c) tayul d) All of these 5. What is the approximately altitude of Rohtang Pass which in gateway to Lahul and Spiti? a) 11000 ft b) 13050 ft c) 14665 ft d) 14875 ft 6. Chamba princely state possessed more than 150 Copper plate tltle deads approximately how many of them belong to pre-Mohammedan period? a) Zero b) Two c) five d) seven 7. Which section of Gaddis of H.P claim that their ancestors fled from Lahore to escape persecution during the early Mohammedan invasion? a) Rajput Gaddis b) Braham in Gaddis CHANDIGARH: SCO: 72-73, 1st Floor, Sector-15D, Chandigarh, 160015 SHIMLA: Shushant Bhavan, Near Co-operative Bank, Chhota Shimla 3 c) Khatri Gaddis d) None of these 8. Which of the following sub-castes accepts of firing in the name of dead by performing the death rites? a) Bhat b) Khatik c) Acharaj d) Turi’s 9. -

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

OBITUARY Bravo Raja Sahib (1923-2010)

OBITUARY Bravo Raja Sahib (1923-2010) On Friday May 7th 2010 Raja Mumtaz Quli Khan passed away peacefully at his home in Lahore. Physically debilitated but mentally active and alert till his death. His death is most acutely felt by his family but poignantly experienced by all with whom he was associated as he was deeply admired by his students, patients, colleagues and friends. In him we have lost a giant in ophthalmology and the father of Ophthalmological Society of Pakistan. His sad demise marks the end of an era. It is difficult to adequately document and narrate the characteristics and qualities which made him such a dedicated teacher, organizer and most of all a great friend known as Raja Sahib to all of us. He was an inspiration to his colleagues, to his students and children of his students who ultimately became his students. Raja Sahib was born in a wealthy, land owning family in a remote village of Gadari near Jehlum on July 16th 1923. He went to a local school which was a few miles from his village and he used to walk to school as there were no roads in that area, although with his personal effort and influence he got a road built but many years after leaving school when he had become Raja Sahib. Did metric in 1938 and B.Sc. form F.C College Lahore in 1943 and joined Galancy Medical College Amritser (Pre- partition) and after creation of Pakistan joined K.E. Medical College Lahore. After completing his MBBS in 1948 from KEMC he did his house job with Prof. -

S.No Roll No Name Eng San Mat Sci Soc Cgpa 1 4114130 Adithya Dutt A1 B1

SRI SATHYA SAI HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, PRASANTHI NILAYAM X CLASS BOARD EXAMINATION RESULT 2016-17 S.NO ROLL NO NAME ENG SAN MAT SCI SOC CGPA 1 4114130 ADITHYA DUTT A1 B1 B2 B1 A2 8,40 2 4114131 AJITH R M K A2 B1 B1 B1 B1 8,20 3 4114132 ANANTHA KRISHNAN P M A1 A1 A2 A1 A1 9,80 4 4114133 ANISH K A1 A1 A1 A2 A1 9,80 5 4114134 AYUSH AGRAWAL A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 10,00 6 4114135 BHAVYA CHARAN Y A2 B1 B1 B1 B1 8,20 7 4114136 BHAGAWAN P A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 10,00 8 4114137 BIBHU PRASAD SAHU A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 10,00 9 4114138 JAGANNIL BANERJEE A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 10,00 10 4114139 KESHAV P A1 A2 A2 A2 A2 9,20 11 4114140 MEGHA SAI C A1 A2 A2 A2 A1 9,40 12 4114141 MRUNAL SIMHA K A1 A2 B1 A1 A1 9,40 13 4114142 NAVEEN SAI KUMAR REDDY N A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 10,00 14 4114143 NITHIN KUMAR REDDY U A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 10,00 15 4114144 OM SAI RUKVITH S A1 A2 A2 A1 A2 9,40 16 4114145 PREM SUDHEER REDDY T A1 A1 A2 A1 A1 9,80 17 4114146 PRUTHVI KRISHNA M A1 A1 A2 A1 A1 9,80 18 4114147 RAM PRASAD G A1 A1 A2 A2 A1 9,60 19 4114148 RISHABH TOOR A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 10,00 20 4114149 RISHI G KANNAN A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 10,00 21 4114150 ROHIT MOHUN RAJU N A2 A2 B1 A2 A2 8,80 22 4114151 SAHIL MEHRA A1 B1 B1 B1 A2 8,60 23 4114152 SAI AASHISH D A1 A2 B1 A2 A2 9,00 24 4114153 SAI GOVINDA V A1 A1 A2 A1 A1 9,80 25 4114154 SAI JATHIN RAJU C A1 B2 B2 B1 B1 8,00 26 4114155 SAI KESHAV S A1 A2 A2 A1 A2 9,40 27 4114156 SAI MADHAV B Y A1 B1 B1 A2 A2 8,80 28 4114157 SAI MOHIT GARG A1 A1 A2 A2 A2 9,40 29 4114158 SAI SANATHANN K A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 10,00 30 4114159 SAI SANTOSH N A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 10,00 31 4114160 SAI SATHVIK M V -

J&K Environment Impact Assessment Authority

0191-2474553/0194-2490602 Government of India Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change J&K ENVIRONMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY (at) DEPARTMENT OF ECOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT AND REMOTE SENSING S.D.A. Colony, Bemina, Srinagar-190018 (May-Oct)/ Paryavaran Bhawan, Transport Nagar, Gladni, Jammu-180006 (Nov-Apr) Email: [email protected], website:www.parivesh.nic.in MINUTES OF MEETING OF THE JK ENVIRONMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY HELD ON 15th September, 2020 at 11.00 AM VIA VIDEO CONFERENCING. The following attended the meeting: 1. Mr. Lal Chand, IFS (Rtd.) Chairman, JKEIAA 2. Er. Nazir Ahmad (Rtd. Chief Engineer) Member, JKEIAA 3. Dr. Neelu Gera, IFS PCCF/Director, EE&RS Member Secretary, JKEIAA In pursuance to the Minutes of the Meeting of JKEAC held on 5th & 7th September, 2020, conveyed vide endorsement JKEAC/JK/2020/1870-83 dated:11-09-2020, a meeting of JK Environment Impact Assessment Authority was held on 15th September, 2020 at 11.00 A.M. via video conference. The following Agenda items were discussed: - Agenda Item No: 01, 02 and 03. i) Proposal Nos. SIA/JK/MIN/51865/2020 ii) SIA/JK/MIN/52027/2020 and iii) SIA/JK/MIN/52028/2020 Title of the Cases: iv) Grant of Terms of Reference for River Bed Material in Ujh River at Village- Jogyian, Tehsil Nagri Parole, District-Kathua, Area of Block 8.0 Ha. v) Grant of Terms of Reference for River Bed Material Minor Mineral Block Located in Ujh Rriver at Village Jagain, Tehsil Nagri Parole, District Kathua, Area of Block- 9.65 Ha. vi) Grant of Terms of Reference for River Bed Material Minor Mineral block located in Ujh river at village Jagain, Tehsil Nagri Parole, District Kathua, Area of block- 9.85 Ha. -

Mammalian Diversity and Management Plan for Jasrota Wildlife Sanctuary, Kathua (J&K)

Vol. 36: No. 1 Junuary-March 2009 MAMMALIAN DIVERSITY AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR JASROTA WILDLIFE SANCTUARY, KATHUA (J&K) by Sanjeev Kumar and D.N. Sahi Introduction marked and later surveyed for the presence of the animal. asrota Wildlife Sanctuary, with an area of 10.04 Jkm2, is situated on the right bank of the Ujh Roadside surveys river in district Kathua, J&K State, between 32o27’ These surveys were made both on foot and by and 32o31’ N latitudes and 75o22’ and 75o26’ E vehicle. These were successful particularly in case longitudes. The elevation ranges from 356 to 520 of Rhesus monkeys, which can tolerate the m. Climatic conditions in study area are generally presence of humans and allow the observations dry sub-humid. The summer season runs from to be made from close quarters. Counting was April to mid-July, with maximum summer done and members of different troops were temperatures varying between 36oC to 42oC. The identified by wounds on exposed parts, broken legs winter season runs from November to February. or arms, scars or by some other deformity. Many Spring is from mid-February to mid-April. The times, jackals and hares were also encountered |Mammalian diversity and management plan for Jasrota Wildlife Sanctuary| average cumulative rainfall is 100 cm. during the roadside surveys. The flora is comprised of broad-leaved associates, Point transect method namely Lannea coromandelica, Dendro- This method was also tried, but did not prove as calamus strictus, Acacia catechu, A. arabica, effective as the line transect method and roadside Dalbergia sissoo, Bombax ceiba, Ficus survey. -

OLD FLORIDA BOOK SHOP, INC. Rare Books, Antique Maps and Vintage Magazines Since 1978

William Chrisant & Sons' OLD FLORIDA BOOK SHOP, INC. Rare books, antique maps and vintage magazines since 1978. FABA, ABAA & ILAB Facebook | Twitter | Instagram oldfloridabookshop.com Catalogue of Sanskrit & related studies, primarily from the estate of Columbia & U. Pennsylvania Professor Royal W. Weiler. Please direct inquiries to [email protected] We accept major credit cards, checks and wire transfers*. Institutions billed upon request. We ship and insure all items through USPS Priority Mail. Postage varies by weight with a $10 threshold. William Chrisant & Sons' Old Florida Book Shop, Inc. Bank of America domestic wire routing number: 026 009 593 to account: 8981 0117 0656 International (SWIFT): BofAUS3N to account 8981 0117 0656 1. Travels from India to England Comprehending a Visit to the Burman Empire and Journey through Persia, Asia Minor, European Turkey, &c. James Edward Alexander. London: Parbury, Allen, and Co., 1827. 1st Edition. xv, [2], 301 pp. Wide margins; 2 maps; 14 lithographic plates 5 of which are hand-colored. Late nineteenth century rebacking in matching mauve morocco with wide cloth to gutters & gouge to front cover. Marbled edges and endpapers. A handsome copy in a sturdy binding. Bound without half title & errata. 4to (8.75 x 10.8 inches). 3168. $1,650.00 2. L'Inde. Maurice Percheron et M.-R. Percheron Teston. Paris: Fernand Nathan, 1947. 160 pp. Half red morocco over grey marbled paper. Gilt particulars to spine; gilt decorations and pronounced raised bands to spine. Decorative endpapers. Two stamps to rear pastedown, otherwise, a nice clean copy without further markings. 8vo. 3717. $60.00 3. -

Pahari Miniature Schools

The Art Of Eurasia Искусство Евразии No. 1 (1) ● 2015 № 1 (1) ● 2015 eISSN 2518-7767 DOI 10.25712/ASTU.2518-7767.2015.01.002 PAHARI MINIATURE SCHOOLS Om Chand Handa Doctor of history and literature, Director of Infinity Foundation, Honorary Member of Kalp Foundation. India, Shimla. [email protected] Scientific translation: I.V. Fotieva. Abstract The article is devoted to the study of miniature painting in the Himalayas – the Pahari Miniature Painting school. The author focuses on the formation and development of this artistic tradition in the art of India, as well as the features of technics, stylistic and thematic varieties of miniatures on paper and embroidery painting. Keywords: fine-arts of India, genesis, Pahari Miniature Painting, Basohali style, Mughal era, paper miniature, embroidery painting. Bibliographic description for citation: Handa O.C. Pahari miniature schools. Iskusstvo Evrazii – The Art of Eurasia, 2015, No. 1 (1), pp. 25-48. DOI: 10.25712/ASTU.2518-7767.2015.01.002. Available at: https://readymag.com/622940/8/ (In Russian & English). Before we start discussion on the miniature painting in the Himalayan region, known popularly the world over as the Pahari Painting or the Pahari Miniature Painting, it may be necessary to trace the genesis of this fine art tradition in the native roots and the associated alien factors that encouraged its effloresces in various stylistic and thematic varieties. In fact, painting has since ages past remained an art of the common people that the people have been executing on various festive occasions. However, the folk arts tend to become refined and complex in the hands of the few gifted ones among the common folks. -

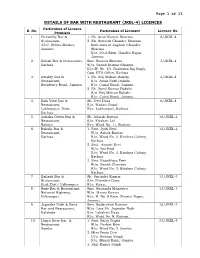

JKEL-4) LICENCES Particulars of Licence S

Page 1 of 13 DETAILS OF BAR WITH RESTAURANT (JKEL-4) LICENCES Particulars of Licence S. No. Particulars of Licensee Licence No. Premises 1. Piccadilly Bar & 1. Sh. Arun Kumar Sharma 2/JKEL-4 Restaurant, 2. Sh. Romesh Chander Sharma 23-C, Nehru Market, both sons of Jagdish Chander Jammu Sharma R/o. 20-A Extn. Gandhi Nagar, Jammu. 2. Satish Bar & Restaurant, Smt. Suman Sharma 3/JKEL-4 Kathua W/o. Satish Kumar Sharma R/o W. No. 10, Chabutra Raj Bagh, Opp. ETO Office, Kathua 3. Kwality Bar & 1. Sh. Brij Mohan Bakshi 4/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Amar Nath Bakshi Residency Road, Jammu R/o. Canal Road, Jammu. 2. Sh. Sunil Kumar Bakshi S/o. Brij Mohan Bakshi R/o. Canal Road, Jammu. 4. Ravi View Bar & Sh. Devi Dass 8/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Madan Gopal Lakhanpur, Distt. R/o. Lakhanpur, Kathua. Kathua. 5. Ashoka Green Bar & Sh. Adarsh Rattan 10/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Krishan Lal Rajouri R/o. Ward No. 11, Rajouri. 6. Bakshi Bar & 1. Smt. Jyoti Devi 12/JKEL-4 Restaurant, W/o. Ashok Kumar Kathua. R/o. Ward No. 3, Krishna Colony, Kathua. 2. Smt . Amarti Devi W/o. Sat Paul R/o. Ward No. 3, Krishna Colony, Kathua. 3. Smt. Kaushlaya Devi W/o. Satish Chander R/o. Ward No. 3, Krishna Colony, Kathua. 7. Kailash Bar & Sh. Surinder Kumar 13/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Pitamber Dass Kud, Distt. Udhampur. R/o. Katra. 8. Roxy Bar & Restaurant, Smt. Sunanda Mangotra 14/JKEL-4 National Highway, W/o. -

Download Book

PREMA-SAGARA OR OCEAN OF LOVE THE PREMA-SAGARA OR OCEAN OF LOVE BEING A LITERAL TRANSLATION OF THE HINDI TEXT OF LALLU LAL KAVI AS EDITED BY THE LATE PROCESSOR EASTWICK, FULLY ANNOTATED AND EXPLAINED GRAMMATICALLY, IDIOMATICALLY AND EXEGETICALLY BY FREDERIC PINCOTT (MEMBER OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY), AUTHOR OF THE HINDI ^NUAL, TH^AKUNTALA IN HINDI, TRANSLATOR OF THE (SANSKRIT HITOPADES'A, ETC., ETC. WESTMINSTER ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO. S.W. 2, WHITEHALL GARDENS, 1897 LONDON : PRINTED BY GILBERT AND KIVJNGTON, LD-, ST. JOHN'S HOUSE, CLEKKENWELL ROAD, E.G. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE IT is well known to aU who have given thought to the languages of India that the or Bhasha as Hindi, the people themselves call is the most diffused and most it, widely important language of India. There of the are, course, great provincial languages the Bengali, Marathi, Panjabi, Gujarat!, Telugu, and Tamil which are immense numbers of spoken by people, and a knowledge of which is essential to those whose lot is cast in the districts where are but the Bhasha of northern India towers they spoken ; high above them both on account of the all, number of its speakers and the important administrative and commercial interests which of attach to the vast stretch territory in which it is the current form of speech. The various forms of this great Bhasha con- of about stitute the mother-tongue eighty-six millions of people, a almost as as those of the that is, population great French and German combined and cover the empires ; they important region hills on the east to stretching from the Rajmahal Sindh on the west and from Kashmir on the north to the borders of the ; the south.