Castes and Caste Relationships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Census Handbook, 13 Jodhpur, Part X a & X B, Series-18

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES 18 RAJASTHAN PARTS XA" XB DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 13. JODHPUR DISTRICT V. S. VERMA O. THE INDIAN ADM'N,STRAnvE SERVICE Olncr.or of Censu.J Operor.lons, Rajasthan The motif on the cover Is a montage presenting constructions typifying the rural and urban areas, set a,amst a background formed by specimen Census notional maps of a urban and a rural block. The drawing has been specially made for us by Shrl Paras Bhansall. LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CeuIlU& of India 1971-Series-18 Rajasthan iii being published in the following parts: Government of India Publications Part I-A General Report. Part I-B An analysis of the demographic, social, cultural and migration patterns. Part I-C Subsidiary Tables. Part II-A General Population Tables. Part II-B Economic Tables. Part II-C(i) Distribution of Popul{.tion, Mother Tongue and Religion, Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes. Part II-CCii) Other Social & Cultural Tables and Fertility Tables, Tables on Household Composition, Single Year Age, Marital Status, Educational Levels, Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes. etc., Bilingualism. Part III-A Report on Establishments. Part II1-B Establishment Tables. Part IV Housing Report and Tables. Part V Special Tables and Notes on Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes. Part VI-A Town Directory. Part VI-B Special Survey Report on Selected Towns. Part VI-C Survey Report on Selected Villages. Part VII Special Report on Graduate and Technical Personnel. Part VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration. } For official use only. Part VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation. Part IX Cen!>us Atlas. Part IX-A Administrative Atlas. -

International Research Journal of Commerce, Arts and Science Issn 2319 – 9202

INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF COMMERCE, ARTS AND SCIENCE ISSN 2319 – 9202 An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust WWW.CASIRJ.COM www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions CASIRJ Volume 5 Issue 12 [Year - 2014] ISSN 2319 – 9202 Eco-Consciousness in Bishnoi Sect Dr. Vikram Singh Associate Professor Vaish College, Bhiwani (Haryana), E-mail: [email protected] The present paper is an endeavor to analyze and elucidate the ‘Eco-Consciousness in Bishnoi Sect’ as Guru Jambheshwar laid twenty-nine principles to be followed by his followers in the region of Marwar. He was a great visionary and it was his scientific vision to protect our environment in the 15th century. A simple peasant, saint, and seer, Jambhuji1 (Guru Jambheshwar 1451-1536 A. D.) knew the importance of bio-diversity preservation and ill–effects of environmental pollution, deforestation, wildlife preservation and ecological balance, etc. He not only learnt it himself, but also had fruit of knowledge to influence the posterity to preserve the environment and ecology through religion. Undoubtedly, he was one of the greatest environmentalist and ecologist of the 15th and 16th century as well as the contemporary of Guru Nanak2 (1469 - 1539) who composed the shabad to lay the foundation for a sacred system for the environmental preservation: Pavan Guru Pani Pita, Mata Dharat Mahat. Pavan means air, which is our Guru, Pani means water, which is our Father, and Mata Dharat Mahat means earth, which is our the Great Mother. ’We honor our Guru’s wisdom by believing that all humans have an intrinsic sensitivity to the natural world, and that a sustainable, more 1 Jambhoji: Messiah of the Thar Desert - Page xiii 2 Burghart, Richard. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

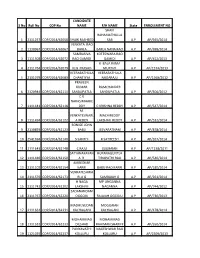

S No Roll No COP No CANDIDATE NAME F/H NAME State

CANDIDATE S No Roll No COP No NAME F/H NAME State ENROLLMENT NO SHAIK RAHAMATHULLA 1 2111257 COP/2014/62058 SHAIK RASHEED SAB A.P AP/945/2014 VENKATA RAO 2 1130967 COP/2014/62067 BARLA BARLA NANA RAO A.P AP/698/2014 SAMBASIVA KOTESWARA RAO 3 1111308 COP/2014/62072 RAO GAMIDI GAMIDI A.P AP/452/2013 K BALA RAMA 4 2111764 COP/2014/62079 KLN PRASAD MURTHY A.P AP/1574/2013 VEERABATHULA VEERABATHULA 5 2131079 COP/2014/62083 CHANTIYYA NAGARAJU A.P AP/1568/2012 PRAVEEN KUMAR RAMCHANDER 6 2120944 COP/2014/62111 SANDUPATLA SANDUPATLA A.P AP/306/2012 C V NARASIMHARE 7 1111441 COP/2014/62118 DDY C KRISHNA REDDY A.P AP/547/2014 M. VENKATESWARL MACHIREDDY 8 1111494 COP/2014/62122 A REDDY LAKSHMI REDDY A.P AP/532/2014 BONIGE JOHN 9 2130893 COP/2014/62123 BABU JEEVARATNAM A.P AP/878/2014 10 2541694 COP/2014/62140 S SANTHI R SATHEESH A.P AP/267/2014 11 2111643 COP/2014/62148 C RAJU SUGRAIAH A.P AP/1238/2011 SATYANARAYAN RUPANAGUNTLA 12 1111480 COP/2014/62150 A R. TIRUPATHI RAO A.P AP/540/2014 AMBEDKAR 13 2131102 COP/2014/62154 KARRI BABU RAO KARRI A.P AP/180/2014 VENKATESHWA 14 2111570 COP/2014/62173 RLU G SAMBAIAH G A.P AP/261/2014 H NAGA MP LINGANNA 15 2111742 COP/2014/62202 LAKSHMI NAGANNA A.P AP/744/2012 SADANANDAM 16 2111767 COP/2014/62220 OGGOJU RAJAIAH OGGOJU A.P AP/736/2013 MADHUSUDAN MOGILAIAH 17 2111661 COP/2014/62231 KACHAGANI KACHAGANI A.P AP/478/2014 MOHAMMAD MOHAMMAD 18 1111532 COP/2014/62233 DILSHAD RAHIMAN SHARIFF A.P AP/550/2014 PUNYAVATHI NAGESHWAR RAO 19 1121035 COP/2014/62237 KOLLURU KOLLURU A.P AP/2309/2013 G SATHAKOTI GEESALA 20 2131021 COP/2014/62257 SRINIVAS NAGABHUSHANAM A.P AP/1734/2011 GANTLA GANTLA SADHU 21 1131067 COP/2014/62258 SANYASI RAO RAO A.P AP/1802/2013 KOLICHALAM NAVEEN KOLICHALAM 22 1111688 COP/2014/62265 KUMAR BRAHMAIAH A.P AP/1908/2010 SRINIVASA RAO SANKARA RAO 23 2131012 COP/2014/62269 KOKKILIGADDA KOKKILIGADDA A.P AP/793/2013 24 2120971 COP/2014/62275 MADHU PILLI MAISAIAH PILLI A.P AP/108/2012 SWARUPARANI 25 2131014 COP/2014/62295 GANJI GANJIABRAHAM A.P AP/137/2014 26 2111507 COP/2014/62298 M RAVI KUMAR M LAXMAIAH A.P AP/177/2012 K. -

Circle District Location Acc Code Name of ACC ACC Address

Sheet1 DISTRICT BRANCH_CD LOCATION CITYNAME ACC_ID ACC_NAME ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3091004 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 5849/22 LAKHAN KOTHARI CHOTI OSWAL SCHOOL KE SAMNE AJMER RA9252617951 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3047504 RAKESH KUMAR NABERA 5-K-14, JANTA COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR, AJMER, RAJASTHAN. 305001 9828170836 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3043504 SURENDRA KUMAR PIPARA B-40, PIPARA SADAN, MAKARWALI ROAD,NEAR VINAYAK COMPLEX PAN9828171299 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002204 ANIL BHARDWAJ BEHIND BHAGWAN MEDICAL STORE, POLICE LINE, AJMER 305007 9414008699 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3021204 DINESH CHAND BHAGCHANDANI N-14, SAGAR VIHAR COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR,AJMER, RAJASTHAN 30 9414669340 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3142004 DINESH KUMAR PUROHIT KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9413820223 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3201104 MANISH GOYAL 2201 SUNDER NAGAR REGIONAL COLLEGE KE SAMMANE KOTRA AJME 9414746796 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002404 VIKAS TRIPATHI 46-B, PREM NAGAR, FOY SAGAR ROAD, AJMER 305001 9414314295 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3204804 DINESH KUMAR TIWARI KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9460478247 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3051004 JAI KISHAN JADWANI 361, SINDHI TOPDADA, AJMER TH-AJMER, DIST- AJMER RAJASTHAN 305 9413948647 [email protected] -

Sacred Groves of India : an Annotated Bibliography

SACRED GROVES OF INDIA : AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Kailash C. Malhotra Yogesh Gokhale Ketaki Das [ LOGO OF INSA & DA] INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY AND DEVELOPMENT ALLIANCE Sacred Groves of India: An Annotated Bibliography Cover image: A sacred grove from Kerala. Photo: Dr. N. V. Nair © Development Alliance, New Delhi. M-170, Lower Ground Floor, Greater Kailash II, New Delhi – 110 048. Tel – 091-11-6235377 Fax – 091-11-6282373 Website: www.dev-alliance.com FOREWORD In recent years, the significance of sacred groves, patches of near natural vegetation dedicated to ancestral spirits/deities and preserved on the basis of religious beliefs, has assumed immense anthropological and ecological importance. The authors have done a commendable job in putting together 146 published works on sacred groves of India in the form of an annotated bibliography. This work, it is hoped, will be of use to policy makers, anthropologists, ecologists, Forest Departments and NGOs. This publication has been prepared on behalf of the National Committee for Scientific Committee on Problems of Environment (SCOPE). On behalf of the SCOPE National Committee, and the authors of this work, I express my sincere gratitude to the Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi and Development Alliance, New Delhi for publishing this bibliography on sacred groves. August, 2001 Kailash C. Malhotra, FASc, FNA Chairman, SCOPE National Committee PREFACE In recent years, the significance of sacred groves, patches of near natural vegetation dedicated to ancestral spirits/deities and preserved on the basis of religious beliefs, has assumed immense importance from the point of view of anthropological and ecological considerations. During the last three decades a number of studies have been conducted in different parts of the country and among diverse communities covering various dimensions, in particular cultural and ecological, of the sacred groves. -

What Is an Environmental Movement? Major Environmental Movements In

What is an Environmental Movement? • An environmental movement can be defined as a social or political movement, for the conservation of environment or for the improvement of the state of the environment. The terms ‘green movement’ or ‘conservation movement’ are alternatively used to denote the same. • The environmental movements favour the sustainable management of natural resources. The movements often stress the protection of the environment via changes in public policy. Many movements are centred on ecology, health and human rights. • Environmental movements range from the highly organized and formally institutionalized ones to the radically informal activities. • The spatial scope of various environmental movements ranges from being local to the almost global. The environmental movements have for long been classified as violent/non-violent, Gandhian/Marxian, radical/ mai11strcam, deep/shallow, mainstream/grassroots, etc. A Local Grassroots Environmental Movement (LGEM) as a movement fighting a particular instance of pollution in a geographically specified region. Local Grassroots Environmental Movements have a limited range of goals that are tied to specific problems. Major Environmental Movements in India Some of the major environmental movements in India during the period 1700 to 2000 are the following. 1.Bishnoi Movement • Year: 1700s • Place: Khejarli, Marwar region, Rajasthan state. • Leaders: Amrita Devi along with Bishnoi villagers in Khejarli and surrounding villages. • Aim: Save sacred trees from being cut down by the king’s soldiers for a new palace. What was it all about: Amrita Devi, a female villager could not bear to witness the destruction of both her faith and the village’s sacred trees. She hugged the trees and encouraged others to do the same. -

Downloaded to a Hand-Held Microcomputer Running the GPSGO Mapping Program Under Windows 6 (Craporola Software Inc)

A mark-resight survey method to estimate the roaming dog population in three cities in Rajasthan, India Hiby et al. Hiby et al. BMC Veterinary Research 2011, 7:46 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1746-6148/7/46 (11 August 2011) Hiby et al. BMC Veterinary Research 2011, 7:46 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1746-6148/7/46 METHODOLOGYARTICLE Open Access A mark-resight survey method to estimate the roaming dog population in three cities in Rajasthan, India Lex R Hiby1*, John F Reece2, Rachel Wright3, Rajan Jaisinghani4, Baldev Singh4 and Elly F Hiby5 1. Abstract Background: Dog population management is required in many locations to minimise the risks dog populations may pose to human health and to alleviate animal welfare problems. In many cities in India, Animal Birth Control (ABC) projects have been adopted to provide population management. Measuring the impact of such projects requires assessment of dog population size among other relevant indicators. Methods: This paper describes a simple mark-resight survey methodology that can be used with little investment of resources to monitor the number of roaming dogs in areas that are currently subject to ABC, provided the numbers, dates and locations of the dogs released following the intervention are reliably recorded. We illustrate the method by estimating roaming dog numbers in three cities in Rajasthan, India: Jaipur, Jodhpur and Jaisalmer. In each city the dog populations were either currently subject to ABC or had been very recently subject to such an intervention and hence a known number of dogs had been permanently marked with an ear-notch to identify them as having been operated. -

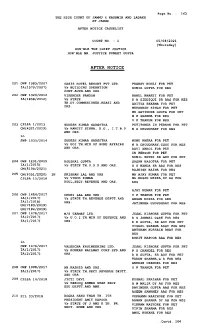

Causelist Dated:- 05-08-2021

Page No. : 163 THE HIGH COURT OF JAMMU & KASHMIR AND LADAKH AT JAMMU AFTER NOTICE CAUSELIST COURT NO. : 1 05/08/2021 [Thursday] HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PUNEET GUPTA AFTER NOTICE 201 OWP 1083/2007 OASIS HOTEL RESORT PVT.LTD. PRANAV KOHLI FOR PET IA(1570/2007) Vs BUILDING OPERATION SONIA GUPTA FOR RES CONT.AUTH.AND ORS. 202 OWP 1329/2012 VIRENDER PANDOH RAHUL BHARTI FOR PET IA(1858/2012) Vs STATE H A SIDDIQUI SR AAG FOR RES TH.DY.COMMSSIONER,REASI AND ADITYA SHARMA FOR PET ORS. MEHARBAN SINGH FOR PET MR.SATINDER GUOTA FOR PET M P SHARMA FOR RES O P THAKUR FOR RES 203 CPLPA 1/2013 SUDESH KUMAR GARGOTRA PETITONER IN PERSON FOR PET CM(4321/2019) Vs RANJIT SINHA, D.G., I.T.B.P N A CHOUDHARY FOR RES AND ORS. in SWP 1035/2014 SUDESH KUMAR GARGOTRA NONU KHERA FOR PET Vs UOI TH.MIN.OF HOME AFFAIRS N A CHOUDHARY,CGSC FOR RES AND ORS. RAVI ABROL FOR PET IN PERSON FOR PET SUNIL SETHI SR ADV FOR PET 204 OWP 1231/2015 KOUSHAL GUPTA GAGAN BASOTRA FOR PET IA(1/2015) Vs STATE TH.U.D.D.AND ORS. S S NANDA SR AAG FOR RES CM(5108/2021) RAJNISH RAINA FOR RES 205 CM(6351/2020) IN KRISHAN LAL AND ORS MR.AJAY KUMAR FOR PET CPLPA 15/2016 Vs VINOD KUMAR MR.EHSAN MIRZA,DY.AG FOR KOUL,SECY.REVENUE AND ORS. RES AJAY KUMAR FOR PET 206 OWP 1454/2017 CHUNI LAL AND ORS. -

Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in a Subregion of Far Western Nepal Walter F

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 4 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin, Monsoon Article 7 1984 1984 Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in A Subregion of Far Western Nepal Walter F. Winkler Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Winkler, Walter F. (1984) "Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in A Subregion of Far Western Nepal," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 4: No. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol4/iss2/7 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ... ORAL HISTORY AND THE EVOLUTION OF THAKUR! POLITICAL AUTHORITY IN A SUBREGION OF FAR WESTERN NEPAL Walter F. Winkler Prologue John Hitchcock in an article published in 1974 discussed the evolution of caste organization in Nepal in light of Tucci's investigations of the Malia Kingdom of Western Nepal. My dissertation research, of which the following material is a part, was an outgrowth of questions John had raised on this subject. At first glance the material written in 1978 may appear removed fr om the interests of a management development specialist in a contemporary Dallas high technology company. At closer inspection, however, its central themes - the legitimization of hierarchical relationships, the "her o" as an organizational symbol, and th~ impact of local culture on organizational function and design - are issues that are relevant to industrial as well as caste organization. -

(2003) Paper Abstracts

Note: Abstracts exceeding the 150-word limit were abbreviated at approximately 175 words and marked with an ellipsis. Abraham, Shinu, University of Pennsylvania Modeling Social Complexity in Late Iron Age/Early Historic Tamilakam This paper evaluates social complexity of the South Indian region known as Tamilakam, comprising the states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu during the late Iron Age/Early Historic period. Tamilakam does not appear to conform to traditionally conceived forms of social organization, making it necessary to consider alternative models within which social complexity can be addressed through an analysis of material remains and their patterning. New mortuary, settlement, and ceramic data from a regional survey of the Palghat Gap in Kerala, South India, is considered and evaluated in the context of prevailing text-based reconstructions of the period. This approach for understanding early Tamil material culture does not ignore the historical record, but instead seeks to integrate the historical and archaeological records more tightly and explicitly. This study has been structured around the analysis of two bodies of material data--megaliths and ceramics--in conjunction with the analysis of historical documents, and concludes that the archaeological data from Iron Age/Early Historic Tamilakam can be better understand with the application of heterarchical principles to early Tamil society. Adamjee, Qamar, New York University Uniting Modernity and Tradition: The Art of Shahzia Sikander The scale, styles, superb draftsmanship and overall rich appearance of Shahzia Sikander’s paintings immediately recall some of the most memorable examples of Persian and Indian painting traditions from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries. Yet a closer look at the images reveals a far more complex dynamic, one deeply-rooted in contemporary issues and not simply a revival of traditional styles. -

Haryana Government Gazette

Haryana Government Gazette EXTRAORDINARY Published by Authority © Govt. of Haryana No. 21-2021/Ext.] CHANDIGARH, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2021 (MAGHA 20, 1942 SAKA) HARYANA GOVERNMENT PERSONNEL DEPARTMENT Notification The 9th February, 2021 No. 42/1/2018-5SII – In pursuance of the Rule 11(1) of the Haryana Civil Services (Executive Branch) Rules, 2008 and in supersession of Notification No. 42/1/95-5SII, dated 6th November, 2008, the Governor of Haryana is pleased to order that the syllabi for the Preliminary Examination as well as Main Written Examination for the posts of Haryana Civil Service (Executive Branch) and Allied Services shall be as under:- SYLLABI FOR THE PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION 1. GENERAL STUDIES General Science. Current events of national and international importance. History of India and Indian National Movement. Indian and World Geography. Indian Culture, Indian Polity and Indian Economy. General Mental Ability. Haryana-Economy and people. Social, economic and culture institutions and language of Haryana. Questions on General Science will cover general appreciation and understanding of science including matters of everyday observation and experience, as may be expected of a well educated person who has not made a special study of any particular scientific discipline. In current events, knowledge of significant national and international events will be tested. In History of India, emphasis will be on broad general understanding of the subject in its social, economic and political aspects. Questions on the Indian National Movement will relate to the nature and character of the nineteenth century resurgence, growth of nationalism and attainment of Independence. In Geography, emphasis will be on Geography of India.