Chinese Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teahouses and the Tea Art: a Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie Master's Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 – 60 Credits – Autumn 2015) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 24 November, 2015 © LI Jie 2015 Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie http://www.duo.uio.no Print: University Print Center, University of Oslo II Summary The subject of this thesis is tradition and the current trend of tea culture in China. In order to answer the following three questions “ whether the current tea culture phenomena can be called “tradition” or not; what are the changes in tea cultural tradition and what are the new features of the current trend of tea culture; what are the endogenous and exogenous factors which influenced the change in the tea drinking tradition”, I did literature research from ancient tea classics and historical documents to summarize the development history of Chinese tea culture, and used two month to do fieldwork on teahouses in Xi’an so that I could have a clear understanding on the current trend of tea culture. It is found that the current tea culture is inherited from tradition and changed with social development. Tea drinking traditions have become more and more popular with diverse forms. -

The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English

NCUE Journal of Humanities Vol. 6, pp. 47-64 September, 2012 The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English Chia-hui Liao∗ Abstract Translation and reception are inseparable. Translation helps disseminate foreign literature in the target system. An evident example is Ezra Pound’s translation based on the 8th-century Chinese poet Li Bo’s “The River-Merchant’s Wife,” which has been anthologised in Anglophone literature. Through a diachronic survey of the translation of classical Chinese poetry in English, the current paper places emphasis on the interaction between the translation and the target socio-cultural context. It attempts to stress that translation occurs in a context—a translated work is not autonomous and isolated from the literary, cultural, social, and political activities of the receiving end. Keywords: poetry translation, context, reception, target system, publishing phenomenon ∗ Adjunct Lecturer, Department of English, National Changhua University of Education. Received December 30, 2011; accepted March 21, 2012; last revised May 13, 2012. 47 國立彰化師範大學文學院學報 第六期,頁 47-64 二○一二年九月 中詩英譯與接受現象 廖佳慧∗ 摘要 研究翻譯作品,必得研究其在譯入環境中的接受反應。透過翻譯,外國文學在 目的系統中廣宣流布。龐德的〈河商之妻〉(譯寫自李白的〈長干行〉)即一代表實 例,至今仍被納入英美文學選集中。藉由中詩英譯的歷時調查,本文側重譯作與譯 入文境間的互動,審視前者與後者的社會文化間的關係。本文強調翻譯行為的發生 與接受一方的時代背景相互作用。譯作不會憑空出現,亦不會在目的環境中形成封 閉的狀態,而是與文學、文化、社會與政治等活動彼此交流、影響。 關鍵字:詩詞翻譯、文境、接受反應、目的/譯入系統、出版現象 ∗ 國立彰化師範大學英語系兼任講師。 到稿日期:2011 年 12 月 30 日;確定刊登日期:2012 年 3 月 21 日;最後修訂日期:2012 年 5 月 13 日。 48 The Reception and Translation of Classical Chinese Poetry in English Writing does not happen in a vacuum, it happens in a context and the process of translating texts form one cultural system into another is not a neutral, innocent, transparent activity. -

The Study on Translation of Chai Tou Feng by Lu You Based on House's

Advances in Intelligent Systems Research, volume 163 8th International Conference on Management, Education and Information (MEICI 2018) The Study on Translation of Chai Tou Feng by Lu You Based on House’s Translation Quality Assessment Mode Xiaoyan Wu Secondary Vocational and Technical School, Yingcheng, Hubei [email protected] Keywords: House’s Model of Translation Quality Assessment; Chai Tou Feng; Applicability Abstract. Song Ci is a kind of unique literary form in the history of Chinese culture, so it is difficult to translate it into English. This thesis applies House’s model of translation quality assessment to evaluate the English version of Chai Tou Feng by Lu You, which demonstrates its applicability and is helpful to future research of Tang poetry and Song Ci. Introduction Translation Quality Assessment Model, which was put forward by Juliane House in A Model of Translation Quality Assessment and Translation Quality Assessment: A Model Revisited, is considered as the first completely theoretical and practical translation quality assessment model in the field of international translation criticism. It is common to find out that a number of Chinese proses and novels were assessed by some theories, such as Transformational Generative Grammar and Equivalence Theory and so on. However, it is rare to follow House’s Translation Quality Assessment Model to assess literary works, especially Tang poetry and Song Ci, which occupy important positions in the ancient Chinese literature. Therefore, this thesis applies House’s Translation Quality Assessment Model to analyzing Chai Tou Feng by Lu You and its English version. On one hand, it helps us to apply abstract translation theories to analyzing literary works, films and Tv series; on the other hand, it contributes to spreading Chinese culture to the world, which enables the world to learn China better. -

How Could Phenological Records from the Chinese Poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-122 Preprint. Discussion started: 28 September 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. How could phenological records from the Chinese poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) be reliable evidence of past climate changes? Yachen Liu1, Xiuqi Fang2, Junhu Dai3, Huanjiong Wang3, Zexing Tao3 5 1School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China 2Faculty of Geographical Science, Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Natural Disaster MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China 3Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), Beijing, 100101, China 10 Correspondence to: Zexing Tao ([email protected]) Abstract. Phenological records in historical documents have been proved to be of unique value for reconstructing past climate changes. As a literary genre, poetry reached its peak period in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) in China, which could provide abundant phenological records in this period when lacking phenological observations. However, the reliability of phenological records from 15 poems as well as their processing methods remains to be comprehensively summarized and discussed. In this paper, after introducing the certainties and uncertainties of phenological information in poems, the key processing steps and methods for deriving phenological records from poems and using them in past climate change studies were discussed: -

An Explanation of Gexing

Front. Lit. Stud. China 2010, 4(3): 442–461 DOI 10.1007/s11702-010-0107-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE XUE Tianwei, WANG Quan An Explanation of Gexing © Higher Education Press and Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Gexing 歌行 is a historical and robust prosodic style that flourished (not originated) in the Tang dynasty. Since ancient times, the understanding of the prosody of gexing has remained in debate, which focuses on the relationship between gexing and yuefu 乐府 (collection of ballad songs of the music bureau). The points-of-view held by all sides can be summarized as a “grand gexing” perspective (defining gexing in a broad sense) and four major “small gexing” perspectives (defining gexing in a narrow sense). The former is namely what Hu Yinglin 胡应麟 from Ming dynasty said, “gexing is a general term for seven-character ancient poems.” The first “small gexing” perspective distinguishes gexing from guti yuefu 古体乐府 (tradition yuefu); the second distinguishes it from xinti yuefu 新体乐府 (new yuefu poems with non-conventional themes); the third takes “the lyric title” as the requisite condition of gexing; and the fourth perspective adopts the criterion of “metricality” in distinguishing gexing from ancient poems. The “grand gexing” perspective is the only one that is able to reveal the core prosodic features of gexing and give specification to the intension and extension of gexing as a prosodic style. Keywords gexing, prosody, grand gexing, seven-character ancient poems Received January 25, 2010 XUE Tianwei ( ) College of Humanities, Xinjiang Normal University, Urumuqi 830054, China E-mail: [email protected] WANG Quan International School, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing 100029, China E-mail: [email protected] An Explanation of Gexing 443 The “Grand Gexing” Perspective and “Small Gexing” Perspective Gexing, namely the seven-character (both unified seven-character lines and mixed lines containing seven character ones) gexing, occupies an equal position with rhythm poems in Tang dynasty and even after that in the poetic world. -

Chinese Poetry and Its Institutions

Chinese Poetry and Its Institutions Pauline Yu (余寶琳) University of California, Los Angeles In a recent interview the American poet Jorie Graham offers an illurninating account of what, in her view, poe t:ry白 , 缸ld how it is produced. Graham is, even for seasoned critics, something of a cballenge to read, someone whose work takes on 1 訂ge issues with startling imagerγand nonlinear leaps of 出 ough t. For her, poe甘y uses “language in a special way-not to report or record experience, but to create experience in a m缸mer that would be 世1- possible without the medium of words. ‘In poe訂y you bave to feel deeply something inchoate, something which is coming up 企om a place 出 at you don't even know the register of,' sbe says."l Her description of how she writes is, unsurprisingly, poetic and, indeed, syn 自由 etic: “ I need to be in an app訂 ently empty frame of mind, without the noise of thinking so h訂 d. You 訂e 甘ying to hear the music of yo叮 own t趾nking in poe甘 y , and ifyou have silence around you, it helps. I have never known where I'm going to st訂t. Often there's a music, or sound, or an image that 伊aws . It invites the senses to do a kind ofwork you don't quite bave ins甘uctions for. Then ques tions attach themselves to a current that feels, perhaps, more ancient. A good poem is always a reaction, a moment of acute surprise that occurred in the soul of the speaker. You want to go somewhere you haven't been before. -

REVISED DRAFT for Entertext

EnterText 5.3 J. GILL HOLLAND Teaching Narrative in the Five-Character Quatrain of Li Po 1 The pattern of complication and resolution within the traditional five-character quatrain (chüeh-chü, jueju) of “Ancient Style poetry” (ku-shih, gushi) of Li Po (Li Bo, Li Bai; 701-762) goes a long way toward explaining Burton Watson’s high praise of Li Po’s poetry: “It is generally agreed that [Li Po] and Tu Fu raised poetry in the shih form to its highest level of power and expressiveness.”1 To his friend Tu Fu, Li Po left the “compact and highly schematized form of Regulated Verse” (lü-shih, lushi), which was deemed the ideal poetic form in the High T’ang of the eighth century.2 Before we begin, we must distinguish between Ancient Style poetry, which Li Po wrote, and the more celebrated Regulated Verse. The purpose of this essay is to explain the art of Li Po’s quatrain in a way that will do justice to the subtlety of the former yet avoid the enormous complexities of the latter.3 The strict rules dictating patterns of tones, parallelism and caesuras of Regulated Verse are not the subject of our attention here. A thousand years after Li Po wrote, eight of his twenty-nine poems selected for the T’ang-shih san-pai-shou (Three Hundred Poems of the T’ang Dynasty, 1763/1764), J. Gill Holland: The Five-Character Quatrain of Li Po 133 EnterText 5.3 the most famous anthology of T’ang poetry, are in the five-character quatrain form.4 Today even in translation the twenty-character story of the quatrain can be felt deeply. -

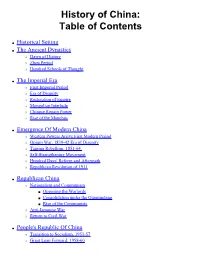

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

The Political Symbolism of Chinese Timber Structure: a Historical Study of Official Construction in Yingzao-Fashi

The Political Symbolism of Chinese Timber Structure: a historical study of official construction in Yingzao-fashi Pengfei Ma A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Built Environment 2020 Surname/Family Name : Ma Given Name/s : Pengfei Abbreviation for degree as give in the University calendar : PhD Faculty : Faculty of Built Environment School : School of Built Environment Thesis Title : The Political Symbolism of Chinese Timber Structure: a historical study of official construction in Yingzao-fashi Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This research presents a historical study of timber construction in the official building code Yingzao-fashi from the lens of politics. The longevity of Chinese civilisation is associated with the ephemeral but renewable timber structure of Chinese buildings. Such an enduring and stable tie, to a large extent, should be attributed to the adaptability of timber structures to the premodern Chinese political system. The inquiry and analysis of the research are structured into three key aspects — the impetus of Yingzao-fashi, official construction systems, the political symbolism of and literature associated with timber structure. The areas of inquiry are all centred on the research question: how did Chinese timber structure of different types serve premodern Chinese politics? First, Yingzhao-fashi has been studied by scholars mainly from a technical point of view, but it was a construction code designed to realise the agenda of political reform. Secondly, the main classifications of timber structures in Yingzao-fashi – diange and tingtang – possessed distinct construction methods of vertical massing and horizontal connection respectively. These two methods, emphasising different architectural elements, are identified as two construction systems created for royal family and officials: royal construction and government construction. -

Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou Meng

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses) Department of History March 2007 Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng Carina Wells [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors Wells, Carina, "Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng" (2007). Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses). 6. https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/6 A Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Faculty Advisor: Siyen Fei This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng Comments A Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Faculty Advisor: Siyen Fei This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/6 University of Pennsylvania Authorial Disputes: Private Life and Social Commentary in the Honglou meng A senior thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in History by Carina L. Wells Philadelphia, PA March 23, 2003 Faculty Advisor: Siyen Fei Honors Director: Julia Rudolph Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………...i Explanatory Note…………………………………………………………………………iv Dynasties and Periods……………………………………………………………………..v Selected Reign -

Book of Lieh-Tzu / Translated by A

ft , I ' * * < The B 2 I it* o f Lieh- i - I /\ Classic of Tao i > *• A Translated by A. C. GRAHAM . t The Book o f Lieh-tzu A Classic o f the Tao translated by A. C. GRAHAM Columbia University Press New York Columbia University Press Morningside Edition 1990 Columbia University Press New York Copyright © 1960, 1990 by A. C. Graham Preface to the Morningside Edition copyright © 1990 by Columbia University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lieh-tzu, 4th cent. B.C. [Lieh-tzu. English] The book of Lieh-tzu / translated by A. C. Graham, p cm.—(Translations from the Oriental classics) Translation of: Lieh-tzu. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-231-07236-8 ISBN 0-231-07237-6 (pbk.) I Graham, A. C. (Angus Charles) II. Title. III. Series. BL1900.L482E5 1990 181'.114-dc2o 89-24°35 CIP All rights reserved Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 p 10 9 8 Translations from the Asian Classics EDITORIAL BOARD Wm. Theodore de Bury, Chair Paul Anderer Irene Bloom Donald Keene George A. Saliba Haruo Shirane David D. W. Wang Burton Watson Contents Preface to the Morningside Edition xi Preface xvii Dramatis Personae xviii—xix Introduction i HEAVEN'S GIFTS 14 2 THE YELLOW EMPEROR 32 3 KING MU OF CHOU 58 4 CONFUCIUS 74 5 THE QUESTIONS OF T'ANG 92 6 ENDEAVOUR AND DESTINY 118 7 YANG CHU 135 8 EXPLAINING CONJUNCTIONS t58 Short Reading List 182 Textual Notes 183 i x Preface to the Morningside Edition A significant change since this book was first published in 196o is that we have learned to see philosophical Taoism in a new historical perspective. -

An Exploration Into the Elegant Tastes of Chinese Tea Culture

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 5, No. 2; 2013 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education An Exploration into the Elegant Tastes of Chinese Tea Culture Hongliang Du1 1 Foreign Language Department, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou, China Correspondence: Hongliang Du, Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, 5 Dongfeng Road, Jinshui District, Zhengzhou 450002, China. Tel: 86-138-380-659-16. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 13, 2013 Accepted: February 19, 2013 Online Published: March 8, 2013 doi:10.5539/ach.v5n2p44 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v5n2p44 This research is funded by Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (11YJA751011). Abstract China was the first to produce tea and consumed the largest quantities and its craftsmanship was the finest. During the development of Chinese history, Chinese Tea culture came into being. In ancient China, drinking tea is not only a very common phenomenon but also an elegant taste for men of letters and officials. Chinese tea culture is extensive and profound and it is necessary for foreigners to understand Chinese tea culture for the purpose of smooth and deepen the communication with the Chinese people. Keywords: tea culture, elegant taste, cultural communication 1. Introduction Chinese tea culture is a unique phenomenon about the production and drinking of tea. There is an old Chinese saying which goes, “daily necessaries are fuel, rice, oil, salt, soy sauce, vinegar and tea” (Zhu, 1984: 106). Drinking tea was very common in ancient China. Chinese tea culture is of a long history, profound and extensive.