Does Safeguards Need Saving? Lessons from the Ukraine–Passenger Cars Dispute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EUROCAR GROUP Global Factors That Determine the Low Cost Production

Ukraine as extended production facility for global car and components manufacturers Elena Chepizhko Head of Government & External Relations EUROCAR GROUP Global factors that determine the low cost production Low cost of Ukraine can integrate production YES into the global value Integration into chains as the “second High added global value value: China” in low cost chains production. YES, > 70% Potential LOW COST Global production using PRODUC high-tech developments TION Low logistics and the world's leading High level of costs “know-how” under employment: YES, 1=6 Industry 4.0 approach Presence of YES own and participation in manufacturing global value chains base / proximity to sources of raw materials YES 2 Global automotive trends: Ukrainian choices Alternative 1 Global production using the Added value resource base and low-skilled up to 14% labor Alternative 2 Ukraine – the second China in low Added value cost production Global production using high-tech >50% developments and the world's leading “know-how” under Industry 4.0 approach 3 * World Bank data 2013 Exemplary case 74 factories around the world extended production facilities built under low cost 37 production principle 4 Ukraine as low cost production site Developers of automotive Extended production facilities technologies (OEMs) Germany China Slovakia Czech Republic USA France Turkey Romania Japan South Korea China Ukraine? 5 Competitive advantages of Ukraine Logistics international 4 transport corridors seaports 18 (including Crimea) 11 river ports 22 kilometers of k. railways -

Business Herald International Law&Business Business New S in T E R

1 digest nationaL economic reLations Law&business business news internationaL ter n i s w e n s s e n i s u b s s e n i s u b & w a E L C STRY U ND I CHAMBER COMMER OF AND UKRAINIAN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS HERALD business news ing for the new markets, the Klei UKRAINE AND SAUDI ARABIA struction cost is estimated at 700-800 Adhesive Machinery implements the WILL JOINTLY CONSTRUCT AIR- mln dollars. international quality standards, ISO PLANES The Ukrlandfarming structure 9001 including, and develops pro- includes 111 horizontal grain storage duction. «Taqnia Aeronotics», a daughter facilities, 6 seed plants, 6 enimal feed entity of the Saudi company for de- plants, 6 sugar plants and 2 leather The main field of the company activity – supply of hi-tech equipment velopment and investments and «An- producing plants as well as an egg to glue various materials. The com- tonov» State company have signed products plant «Imperovo Foods», 19 pany designers develop machines the agreement on development and poultry-breeding plants, 9 hen farms, according to the client requirements production of the light transport plane 3 poultry farms, 3 selection breeding and their high-class specialists ma- An- 132 in Saudi Arabia. The main farms, 3 long-term storage facilities terialize their ideas in metal. That’s goal of the agreement is to fulfill a and 19 meat-processing plants. number of tasks in aviation construc- why the company machines meet tion and technology transfer to Saudi the world requirements. But they are Arabia as well as to train Saudi per- much cheaper. -

European Business Club

ASSOCIATION АССОЦИАЦИЯ OF EUROPEAN BUSINESSES ЕВРОПЕЙСКОГО БИЗНЕСА РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ, RUSSIAN FEDERATION 127473 Москва ул. Краснопролетарская, д. 16 стр. 3 Ulitsa Krasnoproletarskaya 16, bld. 3, Moscow, 127473 Тел. +7 495 234 2764 Факс +7 495 234 2807 Tel +7 495 234 2764 Fax +7 495 234 2807 [email protected] http://www.aebrus.ru [email protected] http://www.aebrus.ru 12th May, 2012 Moscow PRESS RELEASE The Year Continues Strong for New Cars and Light Commercial Vehicles in Russia • Sales of new passenger cars and LCVs in Russia increased by 14% in April, 2012 • Among the top ten bestselling models so far, ten are locally produced According to the AEB Automobile Manufacturers Committee (AEB AMC), April, 2012 saw the sales of new cars and light commercial vehicles in Russia increase by 14% in comparison to the same period in 2011. This April, 266,267 units were sold; this is 33,189 units more than in April, 2011. From January to April, 2012 the percentage sales of new cars and light commercial vehicles in Russia increased by 18% in comparison to the same period in 2011 or by 135,066 more sold units. David Thomas, Chairman of the AEB Automobile Manufacturers Committee commented: "The solid growth of the Russian automotive market continues into the second quarter. Although the pace of the year on year growth is stabilising to less than 15% in recent months, we still feel that the AEB full year forecast for passenger cars and light commercial vehicles should be increased by 50,000 units to 2.85 mln." -------------------------------------------------------------- Attachments: 1. -

![Pdf [2019-05-25] 21](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2261/pdf-2019-05-25-21-742261.webp)

Pdf [2019-05-25] 21

ISSN 1648-2603 (print) VIEŠOJI POLITIKA IR ADMINISTRAVIMAS ISSN 2029-2872 (online) PUBLIC POLICY AND ADMINISTRATION 2019, T 18, Nr. 3/2019, Vol. 18, Nr. 3, p. 46-58 The World Experience and a Unified Model for Government Regulation of Development of the Automotive Industry Illia A. Dmytriiev, Inna Yu. Shevchenko, Vyacheslav M. Kudryavtsev, Olena M. Lushnikova Department of Economics and Entrepreneurship Kharkiv National Automobile and Highway University 61002, 25 Yaroslav Mudriy Str., Kharkiv, Ukraine Tetiana S. Zhytnik Department of Social Work, Social Pedagogy and Preschool Education Bogdan Khmelnitsky Melitopol State Pedagogical University 72300, 20 Hetmanska Str., Melitopol, Ukraine http://dx.doi.org/10.5755/j01.ppaa.18.3.24720 Abstract. The article summarises the advanced world experience in government regulation of the automotive industry using the example of the leading automotive manufacturing countries – China, Japan, India, South Korea, the USA, and the European Union. Leading approach to the study of this problem is the comparative method that has afforded revealing peculiarities of the primary measures applied by governments of the world to regulate the automotive industry have been identified. A unified model for government regulation of the automotive industry has been elaborated. The presented model contains a set of measures for government support for the automotive industry depending on the life cycle stage (inception, growth, stabilisation, top position, stagnation, decline, crisis) of the automotive industry and the -

Automotive Market in Russia and the CIS Industry Overview February 2010 Contents

Automotive market in Russia and the CIS Industry overview February 2010 Contents Opening statement .............................................................................. 1 Russian economy ..................................................................................2 Russian automotive market in a global context ...................................... 4 Russian automotive industry ................................................................ 6 Light vehicle market ............................................................................. 7 Commercial vehicle (CV) market ......................................................... 10 Automotive components market ..........................................................11 Passenger car loan market .................................................................. 12 Dealership networks ........................................................................... 13 Automotive logistics ........................................................................... 14 CIS automotive markets ...................................................................... 15 Ukraine ......................................................................................... 15 Kazakhstan ................................................................................... 16 Belarus ......................................................................................... 17 Uzbekistan .................................................................................... 18 Ernst & Young’s involvement -

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/334 15 March 2016

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/334 15 March 2016 (16-1479) Page: 1/163 Trade Policy Review Body TRADE POLICY REVIEW REPORT BY THE SECRETARIAT UKRAINE This report, prepared for the first Trade Policy Review of Ukraine, has been drawn up by the WTO Secretariat on its own responsibility. The Secretariat has, as required by the Agreement establishing the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3 of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization), sought clarification from Ukraine on its trade policies and practices. Any technical questions arising from this report may be addressed to Cato Adrian (tel: 022/739 5469); and Thomas Friedheim (tel: 022/739 5083). Document WT/TPR/G/334 contains the policy statement submitted by Ukraine. Note: This report is subject to restricted circulation and press embargo until the end of the first session of the meeting of the Trade Policy Review Body on Ukraine. This report was drafted in English. WT/TPR/S/334 • Ukraine - 2 - CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 7 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Main Features .......................................................................................................... 11 1.2 Economic Developments ............................................................................................ 11 1.3 Developments in Trade ............................................................................................. -

2 General Description of the Russian-Made Vehicle Fleet

;-.. ; : s -- 0--21297 .4 { Public Disclosure Authorized VehicleFle'et Public Disclosure Authorized Characterizationin CentralAsia and, the Caucasus Public Disclosure Authorized Reportfor the RegionalStudy on: CleanerTransportation FuelIs for UrbanAir QualityImprovement Public Disclosure Authorized inCentralAsia -and the Caucasus Vehicle Fleet Characterization in Central Asia and the Caucasus Report for the Regional Study on: Cleaner Transportation Fuels for Urban Air Quality Improvement in Central Asia and the Caucasus Canadian International Development Agency Joint UNDPlWorld Bank Energy Sector ManagementAssistance Programme (ESMAP) Contents Acknowledgments ............................................... vii Abbreviations and Acronyms ............................................... ix Executive Summary ............................................... xi Vehicle Technology in Central Asia and the Caucasus........................................ xii Fleet Octane Requirements ........................................ xiii Inspection and Maintenance Programs ........................................ xiv Uzbekistan's Natural Gas Conversion Program ........................................ xvi Conclusions and Recommendations ....................................... xvii 1 Introduction ................................................ 1 1.1 Objectives .1 1.2 Background .2 Impact of Fuel on Vehicle Emissions .2 Long Range Effects of Emissions .2 Climate Change and Greenhouse Gases .2 Impact of Fuel on Vehicle Technology. 3 1.3 Study Methodology.3 -

Project Document

GEF-7 REQUEST FOR PROJECT ENDORSEMENT/APPROVAL PROJECT TYPE: TYPE OF TRUST FUND: GEFTF PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: Transition towards low and No-Emission Electric Mobility in the Ukraine: Strengthening electric vehicle charging infrastructure and incentives Country(ies): Ukraine GEF Project ID: 10271 GEF Agency(ies): UNEP, EBRD GEF Agency Project ID: 01724 Science and Technology Center in Project Executing Ukraine (STCU), Submission Date: 10 Dec 2020 Entity(s): European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Expected GEF Focal Area (s): Climate Change 1 Sept 2021 Implementation Start: Expected Completion 31 Aug 2025 Date: Global Programme to Support Countries Name of Parent Program Parent Program ID: 10114 with the Shift to Electric Mobility A. FOCAL/NON-FOCAL AREA ELEMENTS (in $) Programming Trust GEF Confirmed Focal Area Outcomes Directions Fund Project Co- Financing financing CCM 1-2 Promote innovation and technology transfer for GEF sustainable energy breakthroughs for electric drive TF 1,601,376 8,190,000 technology and electric mobility Total project costs 1,601,376 8,190,000 B. PROJECT DESCRIPTION SUMMARY Project Objective: To support and enable the Government of Ukraine to make the transformative shift to decarbonize transport systems by promoting electric mobility at national scale Project Compone Project Project Outputs Trust GEF Confirmed Component nt Type Outcomes Fund Project co- Financing financing (US$) (US$) Component 1: Technical Outcome 1: Output 1.1: A national GEF 150,250 70,000 Institutionaliz Assistance The Government multi-stakeholder TF ation of low- of Ukraine advisory group is carbon electric establishes an established for mobility institutional coordination of framework for government strategy, effective policies and actions to coordination, promote e-mobility in develops capacity Ukraine. -

December 2013 Publication of LUKOIL Lubricants Company

Publication of LUKOIL Lubricants Company December 2013 (LLK-International) New Year is a holiday longed for by perhaps all people on Earth. Let the New Year give you belief that it will be a year of new achievements, successes and fulfilments! Be healthy and happy. I wish you a festive spirit! LUKOIL President V. Yu. Alekperov LUKOIL Chairman G. M. Kiradiev CONTENTS 2 HAPPY NEW YEAR! 6 3 FORUM Moscow International Lubricants Week 2013 6 CORPORATE AFFAIRS LUKOIL brand is synonymous with carefully calibrated and effective movement forward 8 PARTNERSHIP Breakthrough in Ukraine 12 10 Northern supply lines 12 LUKOIL lubricants in Georgia 14 LUKOIL lubes for key clients in Romania and Macedonia 16 LUKOIL starts producing lubes in Austria 16 18 Road to China 20 NEWS 20 «МАСЛА@ЛУКОЙЛ» #4 December 2013 "Масла@ЛУКОЙЛ" is a publication of LLK-International Publisher: RPI Address: LLK-International, 6 Malaya Yakimanka, Moscow 119180 Phone: +7 (495) 980 39 12 e-mail: [email protected] Press run: 2,000 The magazine is registered by the Federal Service for Media Law Compliance and Cultural Heritage. Registration certificate ПИ №ФС77-28009 1 Dear Colleagues, Dear friends! t’s a tradition that before New In 2013, we continued supplies IYear we summarize the outgo- to AVTOTOR Company as LUKOIL ing year, thoroughly weigh past de- GENESIS engine oils became the velopments and ask ourselves what first fill lubricants for Opel and has been done. Was it done well? Chevrolet, while LUKOIL gear oils Effectively? How can we improve our became the first fill oils for engines performance? of Hyundai trucks and KIA cars. -

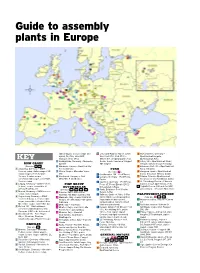

Guide to Assembly Plants in Europe

Guide to assembly plants in Europe station wagon, S-class sedan and B Lieu Saint-Amand, France (Sevel 3 Ruesselsheim, Germany – hybrid, CL, CLS, SLS AMG; Nord: Fiat 50%, PSA 50%) – Opel/Vauxhall Insignia, KEY Maybach (ends 2013) Citroen C8, Jumpy/Dispatch; Fiat Opel/Vauxhall Astra 5 Ludwigsfelde, Germany – Mercedes Scudo, Scudo Panorama; Peugeot 4 Luton, UK – Opel/Vauxhall Vivaro; BMW GROUP Sprinter 807, Expert Renault Trafic II; Nissan Primastar (See also 2 , 20 ) 6 Hambach, France – Smart ForTwo; 5 Ellesmere Port, UK – Opel/Vauxhall 1 Dingolfing, Germany – BMW ForTwo Electric FORD Astra, AstraVan 5-series sedan, station wagon, M5 7 Vitoria, Spain – Mercedes Viano, (See also 7 ) 6 Zaragoza, Spain – Opel/Vauxhall station wagon, 5-series Gran Vito 1 Southampton, UK – Ford Transit Corsa, CorsaVan, Meriva, Combo Turismo, 6-series coupe, 8 Kecskemet, Hungary – Next 2 Cologne, Germany – Ford Fiesta, 7 Gliwice, Poland – Opel/Vauxhall convertible, M6 coupe, convertible, Mercedes A and B class Fusion Astra Classic and Notchback, Zafira 7-series sedan 3 Saarlouis, Germany – Ford Focus, 8 St. Petersburg, Russia – Chevrolet 2 Leipzig, Germany – BMW 1-series FIAT GROUP Focus ST, Focus Electric (2012) Captiva, Cruze; Opel Antara, Astra (3 door), coupe, convertible, i3 AUTOMOBILES first-generation Kuga A Togliatti, Russia (GM and AvtoVAZ (2013), i8 (2014), X1 (See also 33 , 34 , 35 , 45 ) 4 Genk, Belgium – Ford Mondeo, joint venture) – Chevrolet Niva, Viva 3 Munich, Germany – BMW 3-series 1 Cassino, Italy – Alfa Romeo Galaxy, S-Max sedan, station wagon -

Page 1 of 3 2020 2020 July August 1 Prjsc "ZAZ" (Zaporizhia Automobile Building Plant) 9 7 -22,2 Cars

page 1 of 3 Motor vehicle production in Ukraine (units) 2020 2020 № MANUFACTURER % Chg July August PrJSC "ZAZ" (Zaporizhia Automobile 1 9 7 -22,2 Building Plant) Cars 0 0 - CV 0 0 - Buses 9 7 -22,2 PrJSC «AutoKrAZ» (Kremenchuk 2 n/a n/a - Automobile Plant) Cars - CV - Buses - 3 BOGDAN Corporation 0 16 - Cars 0 0 - CV 0 0 - Buses 0 16 - Etalon Corporation: PrJSC "Boryspil 4 0 0 - Autoplant" Cars - CV 0 - Buses 0 - Etalon Corporation: "Chernihiv autoplant" 5 24 30 +25,0 LLC Cars - CV 0 - Buses 24 30 +25,0 6 PrJSC "EUROCAR" 172 38 -77,9 Cars 172 38 -77,9 CV - Buses - 7 PJSC "Chаsiv Yar Buses Plant" 2 5 +150,0 Cars - CV - Buses 2 5 +150,0 8 JSC "Cherkassy Bus" 29 25 -13,8 Cars - CV 4 0 -100,0 Buses 25 25 +0,0 Cars 172 38 -77,9 CV 4 0 -100,0 Buses 60 83 +38,3 TOTAL 236 121 -48,7 © "Ukrautoprom" *PJSC «AUTOKRAZ» data are unavailable since August 2016 page 2 of 3 Motor vehicle production in Ukraine (units) 2019 2020 % Chg № MANUFACTURER August August 20/19 PrJSC "ZAZ" (Zaporizhia Automobile 1 13 7 -46,2 Building Plant) Cars 0 0 - CV 8 0 -100,0 Buses 5 7 +40,0 PrJSC «AutoKrAZ» (Kremenchuk 2 n/a n/a - Automobile Plant) Cars - CV - Buses - 3 BOGDAN Corporation 19 16 -15,8 Cars 0 0 - CV 0 0 - Buses 19 16 -15,8 Etalon Corporation: PrJSC "Boryspil 4 0 0 - Autoplant" Cars - CV 0 - Buses 0 - Etalon Corporation: "Chernihiv autoplant" 5 16 30 +87,5 LLC Cars - CV 0 - Buses 16 30 +87,5 6 PrJSC "EUROCAR" 553 38 -93,1 Cars 553 38 -93,1 CV - Buses - 7 PJSC "Chаsiv Yar Buses Plant" 6 5 -16,7 Cars - CV - Buses 6 5 -16,7 8 JSC "Cherkassy Bus" 61 25 -59,0 Cars - CV 26 0 -100,0 Buses 35 25 -28,6 Cars 553 38 -93,1 CV 34 0 -100,0 Buses 81 83 +2,5 TOTAL 668 121 -81,9 © "Ukrautoprom" *PJSC «AUTOKRAZ» data are unavailable since August 2016 page 3 of 3 Motor vehicle production in Ukraine (units) 2019 2020 % Chg № MANUFACTURER Jan.-Aug. -

El Mercado De La Automoción En Ucrania

Oficina Económica y Comercial de la Embajada de España en Kiev El mercado de les a la automoción en Ucrania NotasSectori 1 El mercado de la automoción en Ucrania Esta nota ha sido elaborada por Diego Micol García bajo la supervisión de la Oficina Económica y Co- mercial de la Embajada de España en Kiev Abril 2009 NotasSectoriales 2 EL MERCADO DE LA AUTOMOCIÓN EN UCRANIA ÍNDICE CONCLUSIONES 4 I. DEFINICION DEL SECTOR 6 1. Delimitación del sector 6 2. Clasificación arancelaria 7 II. OFERTA 8 1. Tamaño del mercado 9 2. Producción local 11 3. Importaciones y Exportaciones 14 4. Competidores Nacionales 16 5. Competidores Extranjeros 20 III. ANÁLISIS CUALITATIVO DE LA DEMANDA 22 1.1 Parque móvil ucraniano 1.2 Análisis cualitativo del parque móvil ucraniano IV. PRECIOS Y SU FORMACIÓN 27 V. PERCEPCIÓN DEL PRODUCTO ESPAÑOL 28 VI. DISTRIBUCIÓN 29 VII. CONDICIONES DE ACCESO AL MERCADO 30 VIII. ANEXOS 32 1. Empresas 32 2. Ferias 33 3. Publicaciones del sector 34 4. Asociaciones 35 5. Otras direcciones de interés 35 Oficina Económica y Comercial de la Embajada de España en Kiev 3 EL MERCADO DE LA AUTOMOCIÓN EN UCRANIA CONCLUSIONES Para la industria de automoción ucraniana se configura una corta pero profunda disminución de la producción en 2009, debido al descenso de la demanda interna que junto con el des- censo de las exportaciones, no serán capaces de compensar el descenso de las ventas, de las que se prevé una bajada comprendida de 10-20%. Desde octubre de 2008, las ventas han sufrido un drástico descenso, a nivel mundial, como consecuencia de los efectos de la contracción del crédito.