Mary Ellen Mark's Representation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

Nyc the Tribeca Show Organized by Carl Glassman and April Koral

Press Release apexart - nyc The Tribeca Show Organized by Carl Glassman and April Koral December 5 - December 21, 2019 291 Church Street, NYC Opening reception: Wednesday, December 4, 6-8pm Featuring work by: Carl Glassman, Staple Street, 1994 Max Blagg Donna Ferrato Carl Glassman Marc Kaczmarek Susan Rosenberg Jones Allan Tannenbaum More than two decades ago Tribeca-the-neighborhood became Tribeca-the-global-brand. Everything from racehorses to rap artists to bars, bracelets, and yachts have taken the name. “It has an ultra-cool, hip and happening feel to it,” said a Los Angeles designer about his new necklace, the Tribeca. Actually, no it doesn’t. Not to those who know the neighborhood. The Tribeca Show undertakes a de-branding of Tribeca through the perspectives of five Tribeca-based photographers and one local poet. Their work, each in a different way, counters the area’s over-hyped reputation for trendiness and glamour. The show is curated by April Koral and Carl Glassman, whose publication, The Tribeca Trib, has been chronicling Tribeca in news, features, and photography for 25 years. Photos by Glassman, a photojournalist and documentary photographer, along with images by photographers Donna Ferrato, Marc Kaczmarek, Susan Rosenberg Jones, and Allan Tannenbaum, along with a new poetry installation by Max Blagg, present a nuanced portrait of the neighborhood across decades that defies the media’s insistent focus on celebrity and wealth. Far more than its famous-but-rarely-seen residents such as Taylor Swift, Beyoncé and Justin Timberlake, or its annual film festival, the neighborhood—one of the city’s oldest—prizes its rich history and preserved 19th-century streetscape. -

Photography in Dialogue

2530 Superior Ave., #403 Cleveland, OH 44114 www.spenational.org Collaborative Exchanges: HOST INSTITUTION Photography in Dialogue 51st SPE National Conference March 6-9, 2014 – Hilton Baltimore, MD Table of Contents GOLD LEVEL SPONSORS 2 Welcome from the Conference Chair 3 Welcome from the Host Institution 4 Sponsors Foldout Conference Schedule 5 Hotel Floor Plan PRESENTATION SCHEDULE & DETAILS Department of Photography 6 Thursday Sessions 9 Friday Sessions 15 Saturday Sessions 20 Presenter Bios & Index SPECIAL EVENTS 28 Daily Special Events Schedule 29 Silent Auction & Raffle 30 Film Festival 33 Book Signing Schedule EXHIBITS FAIR 34 Exhibits Fair Floor Plan & Exhibitor List 35 Sponsor & Exhibitor Contact Information SILVER LEVEL SPONSORS PORTFOLIO CRITIQUES & REVIEWS 38 Portfolio Critiques & Reviews Information 39 Portfolio Reviewers’ Index APPLAUSE 42 Awards & Recognitions 44 SPE Board of Directors, Staff, & Committees 45 Donors GENERAL INFORMATION 46 Map of Baltimore 48 Gallery & Museum Guide 50 Dining & Entertainment Guide 72 2015 Conference Description & Proposal Information Cover Image: Nicholas Kahn and Richard Selesnick, janus-symbiosis, 2010 Program Guide Design: Nina Barcellona Program Guide Co-Editors: Nina Barcellona and Ginenne Clark From The Conference Chair Welcome to Baltimore for the 51st SPE National Conference. Last year’s event celebrated a milestone of fifty years and I hope that this conference marks an auspicious beginning for the next fifty. We’ve worked hard to ensure that it will. The theme is Collaborative Exchanges: Photography in Dialogue. The key word in the title is “dialogue,” and we hope the programming will celebrate artistic practices that employ the photographic image while embracing relationships. This could be a social component, working directly with other artists or writers, creating dialogue with communities, forming collectives or shared resource banks, building public artworks, or otherwise working in expanded practice with others to make new art. -

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2020

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2020 Exhibitions 2 Traveling Exhibitions 3 Film Series at the Dryden Theatre 4 Programs and Events 5 Publishing and Online Projects 7 Books 7 Digitized Films Online 7 Silver Voices 7 Videos 8 Mobile Tour 9 Engagement and Attendance Statistics 10 Education 11 The L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation 11 Photographic Preservation & Collections Management 11 Photography Workshops 12 Loans 13 Object Loans 13 Film Screenings 14 Acquisitions 15 Gifts to the Collections 15 Photography 15 Moving Image 19 Technology 19 George Eastman Legacy 22 Richard and Ronay Menschel Library 22 Purchases for the Collections 22 Photography 22 Moving Image 23 Technology 23 George Eastman Legacy 23 Richard and Ronay Menschel Library 23 Conservation and Preservation 24 Conservation 24 Film Preservation 27 Capital Projects 28 Financial 29 Treasurer’s Report 29 Statement of Financial Position 30 Statement of Activities and Change in Net Assets 31 Fundraising 32 Members 32 Corporate Members 34 Annual Campaign 34 Designated Giving 35 Planned Giving 36 Trustees and Staff 37 Board of Trustees 37 George Eastman Museum Staff 38 George Eastman Museum, 900 East Avenue, Rochester, NY 14607 Exhibitions Exhibitions on view in the museum’s galleries and mansion during 2020. MAIN GALLERIES POTTER PERISTYLE MANSION Anderson & Low: Voyages and Discoveries Penelope Umbrico: Everyone’s Photos Any 100 Years Ago: George Eastman in 1920 Curated by Lisa Hostetler, curator in charge, License (532 of 1,190,505 Full Moons on Flickr) Curated by Jesse Peers, archivist, Department of Photography Curated by Lisa Hostetler, curator in charge, George Eastman Legacy Collection October 19, 2019–January 5, 2020 Department of Photography February 14, 2020–January 3, 2021 July 20, 2019–January 5, 2020 Bea Nettles: Harvest of Memory Made possible by Stephen B. -

GLEN COVE ______Gazette Air Show Kicks Off Scout’S Project Building Her Own Memorial Day Weekend - Marks Ems Week Glen Cove Page 14 Page 18 Page 6 Vol

HERALD________________ GLEN COVE ______________ Gazette air show kicks off scout’s project Building her own Memorial Day weekend - marks eMs Week glen Cove Page 14 Page 18 Page 6 VoL. 26 no. 21 May 25-31, 2017 $1.00 Past is present in Sea Cliff Victorians By Laura Lane homes, offered even more. [email protected] “This gives people an opportu- nity to get to know our commu- Sunday was a day to wel- nity,” said Kennedy as he gazed come outsiders to Sea Cliff. It down Sea Cliff Avenue, which was time for the Sea Cliff Land- had more foot traffic than usual marks Association House Tour, for a Sunday. “This is all done a popular event that is not by volunteers, and it doesn’t offered annually, perhaps due cost the city anything.” to the extensive planning that The volunteers could be surely must be involved. found at all of the homes on the After picking up a map and a tour. They welcomed guests and brochure, visitors embarked on acted as docents. a tour of six Victorian homes Inside Iris Targoff’s Queen in the village. Anne Victorian home on 8th Ave- “This showcases one of the nue, many visitors stopped to things Sea Cliff is most famous admire a chandelier crafted from for — a number of Victorian Murano glass. Two elderly cou- homes,” said Bruce Kennedy, a ples, Russian aristocrats, once former mayor who is now the lived in the home, which was village administrator. Sea Cliff built in 1893. Targoff has been has the most Victorian homes working hard for seven years to Tab Hauser/Herald in New York State, he added. -

One-Year Certificate Programs 2016-2017 General Studies In

ONE-YEAR CERTIFICATE PROGRAMS 2016-2017 GENERAL STUDIES IN PHOTOGRAPHY DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY AND PHOTOJOURNALISM NEW MEDIA NARRATIVES © Fernanda Lenz GS13 COVER © Jiaxi Yang GS15 2 1 CONTENTS One-Year Certificate Programs Letter from the Executive Director 5 Letter from the Dean 7 About the International Center of Photography 9 One-Year Certificate Programs Overview 11 Academic Calendar 13 General Studies in Photography Letter from the Chair 15 Course Outline 21 Alumni and Faculty Q&As 25 Documentary Photography and Photojournalism Letter from the Chair 33 Course Outline 37 Alumni Q&As 45 New Media Narratives Letter from the Chair 51 Course Outline 53 Q&A with the Chair 57 Chairs and Faculty 59 Facilities and Resources 63 Tuition, Fees, and Financial Aid 67 Admissions 71 International Students 71 © Sara Skorgan Teigen GS12 2 16/173 LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR This is an extraordinary moment in the history of photography and image making, as well as in the history of the International Center of Photography. ICP’s founder, Cornell Capa, described photography as “the most vital, effective, and universal means of communication of facts and ideas.” The power of images to cross barriers of language, geography, and culture is greater today than ever before. And in an era of profound change in the way images are made and interpreted, ICP remains the leading forum for provocative ideas, innovation, and debate. As the evolution of image making continues, ICP is expanding to meet new opportunities, with a dynamic new museum space on the Bowery in Manhattan and an expansive new collections facility at Mana Contemporary in Jersey City. -

RIT Digital Archive Home

R·I·T · NEWS & EVENTS Vol. 26, No. 2 September 15, 1994 Multimedia Wiz Pioneers Special Effects School of Photographic Arts and Sciences, the original 17-year-old special-effects and The Shadow. The companies' work the free lecture----0pen to the public-will house in New York City; RGA/LA, the also shows up in Blue Steel, She-Devil, be telecast live via satellite feed to down Los Angeles-based feature projects opera Indecent Proposal, and The Joy Luck Club linked sites. tion; R/GA Print, a pioneer in digital print and in trailers for The Hunt for Red Articles about Greenberg and his co productions; R/GA Interactive, a new October, Ghostbusters, Blade Runner, and founding brother Richard (who now pur multimedia production company; Savoy Blow Out. The American Institute of the sues a directing career on the West Coast) Commercials, a live-action commercial Graphic Arts included many R/GA works describe their directors' firm; in feature films, TV, and trailer graphics in rags-to-riches Michael its exhibition "A Decade of Entertainment Robert M. Greenberg story and Schrom and Graphics: 1982-1992." TV graphics and Robert as "one Company, spe visual effects work include the new open By Laurie Maynard of the leading cializing in ing for "Masterpiece Theatre," main titles pioneers and close-up, for "Michael Jackson Talks ... to Oprah," em ember the "whooshing" letters v1s1onaries in tabletop, and the AT&T "i Plan" TY ads, and the that open the movie Superman? Or the design and in-studio pro computer-animated cars tangoing in the the bouncing baby in The World R production of duction for Shell TV ad campaign. -

Conferring Significance: Celebrating Photography’S Continuum 50Th Anniversary SPE National Conference March 7-10, 2013 – Palmer House Hilton – Chicago

H OST INSTITUTION GD OL LEVEL SPONSORS Conferring Significance: Celebrating Photography’s Continuum 50th Anniversary SPE National Conference March 7-10, 2013 – Palmer House Hilton – Chicago Table of Contents 2 Welcome from the Conference Chair 3 Welcome from the Host Institution SILVER LEVEL SPONSORS 4 Sponsors Foldout Conference Schedule 5 Hotel Floor Plan PRESENTATION SCHEDULE & DETAILS 6 Thursday Sessions 9 Friday Sessions 14 Saturday Sessions 18 Presenter Bios & Index SPECIAL EVENTS 25 Daily Special Events Schedule 26 Silent Auction & Raffle 26 Film Festival 29 Book Signing Schedule PORTFOLIO CRITIQUES & REVIEWS 30 Portfolio Critiques & Reviews Information 31 Portfolio Reviewers’ Bios & Preferences EXHIBITS FAIR 38 Exhibits Fair Floor Plan & Exhibitor List 39 Sponsor & Exhibitor Contact Information Cover Image: Martin Parr, THAILAND, Bangkok, APPLAUSE Grand Palace, 2012 Program Guide Design: Nina Barcellona 42 Awards & Recognitions Program Guide Co-Editors: Nina Barcellona and Ginenne Lanese 44 SPE Board of Directors, Staff, & Committees 45 Donors GENERAL INFORMATION 46 Map of Chicago 2530 Superior Ave., #403 47 Gallery & Museum Guide Cleveland, OH 44114 www.spenational.org 48 Dining & Entertainment Guide 68 2014 Conference Description & Proposal Information From The Conference Chair I’m excited to welcome you to the great city of Chicago for the 50th Anniversary SPE National Conference “Conferring Significance: Celebrating Photography’s Continuum.” Fifty years ago, The Society for Photographic Education’s founders held their first conference in Chicago so it’s fitting to return to where our conferences began to celebrate photography, teaching and SPE. Chicago has a long and significant tradition of photography and photo education. Here, Lazlo Moholy-Nagy established his New Bauhaus, embracing instruction in photography. -

Domestic Violence Resources

Domestic Violence Resource Center ann patricia coleman 1 Domestic Violence Resource Center ann patricia coleman the most current information check out my blog:momsangelsblog.wordpress.com Women’s Shelters: for Women and their Children Hope’s Door: Pleasantville, NY 914-747-0828: Hotline 888-438-8700 Email [email protected] www.HopesDoorNY.org My Sister's Place Contact:Beth Levy:Attorney 1 Water Street White Plains, NY 914-683-1333: Emergency hotline 800-298-7233 Process Server:My Sisters Place referral: orders of protection,court orders State Process Serving Co. 914-243-5817 Domestic Violence Victim Advocate Police Chief :David Ryan Pound Ridge, NY: Police Chief David Ryan:914-764-4206 email:[email protected] Retreats for Battered Women Lundy Bancroft: 413-582-6700 Website and blog: www.lundybancroft.com. Domestic Violence Advocacy for Women and Children: Divorce Attorneys Richard Ducote: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: 412-322-0750: Email [email protected] Charlie and Diane Hofheimer: Virginia Beach, Virginia: 757-425-5200 for women only 2 Resources Alliance for Justice Washington DC office: 202-822-6070 California office: 510-444-6070 American Bar Association Commission on Domestic Violence www.abanet.org/domviol Angela Shelton www.angelashelton.com [email protected] Anne Grant: Providence Journal Freelance writer exposing the failure to protect mothers and children from violence (Rhode Island) http://custodyscam.blogspot.com www.littlehostagesblogspot.com Email: [email protected] ASPCA: 424 East 92nd St.NY,NY 10128 800-628-0028 www.aspca.org Avon:See The Signs www.seethesigns.org Avon Foundation for Women launches employer training program to help bystanders become upstanders when suspecting abuse Battered Mothers Custody Conference www.batteredmotherscustodyconference.org Battered Mothers’ Justice Project 800-903-0111 ext. -

Evidence: Photographic Image, Fact, Document Syllabus

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Open Educational Resources City College of New York 2018 Evidence: Photographic Image, Fact, Document syllabus Ellen Handy CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_oers/25 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Prof. Ellen Handy, Art Dept. [email protected] Class: Wednesday 2:004:50, NAC 6/316 Office hours (in SH 303-C): Mondays 3:00-5:00 and Wednesdays 5:15-6:16 … and by appointment at other times, if necessary. Timothy O’Sullivan, Historic Spanish Record of the Conquest, South Side of Inscription Rock, N.M., 1873, albumen silver print from glass negative Art 31155, 3EF Evidence: Photographic Image, Fact, Document Course description: This interdisciplinary course investigates the status of photographs as evidence in different contexts. How do photographic images serve as evidence in history, science, journalism, anthropology, politics, advertising and popular culture? Is a picture worth a thousand words? Can photographs lie? Should we believe our eyes? What philosophical, technical, political and practical presumptions are involved in the use of photographs as evidence? When and how is photographic evidence contested? Research projects for this course will involve work with primary sources in New York Public Library Collections. Learning Objectives: -

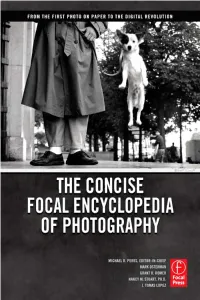

The Concise Focal Encyclopedia of Photography

The Concise Focal Encyclopedia of Photography Prelims-K80998.indd i 6/20/07 6:14:35 PM This page intentionally left blank The Concise Focal Encyclopedia of Photography From the First Photo on Paper to the Digital Revolution MICHAEL R. PERES, MARK OSTERMAN, GRANT B. R OMER, NANCY M. STUART , Ph.D., J. TOMAS LOPEZ AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • O XFORD • PARIS • S AN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • S INGAPORE • S YDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Else vier Prelims-K80998.indd iii 6/20/07 6:14:37 PM Acquisitions Editor : Diane Heppner Publishing Ser vices Manager : George Mor rison Senior Project Manager : Brandy Lilly Associate Acquisitions Editor : Valerie Gear y Assistant Editor : Doug Shults Marketing Manager : Christine Degon V eroulis Cover Design: Alisa Andreola Interior Design: Alisa Andreola Focal Press is an imprint of Else vier 30 Cor porate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford O X2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2008, Else vier Inc. All rights reser ved. No par t of this publication ma y be reproduced, stored in a retrie val system, or transmitted in an y form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocop ying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written per mission of the publisher . Permissions ma y be sought directly from Else vier’s Science & T echnology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: ( ϩ44) 1865 843830, fax: ( ϩ44) 1865 853333, E-mail: per missions@else vier.com. You may also complete your request on-line via the Else vier homepage (http://else vier.com), by selecting “Suppor t & Contact” then “Cop yright and Permission” and then “Obtaining P ermissions. -

The Ethics of Photographic Evidence in the Domestic Violence Trial and Popular Culture

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Visualizing Violence: The Ethics of Photographic Evidence in the Domestic Violence Trial and Popular Culture A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Kelli D. Moore Committee in charge: Professor Patrick Anderson, Chair Professor Lisa Cartwright Professor Kelly Gates Professor Marcel Henaff Professor Roshanak Kheshti 2013 Copyright Kelli D. Moore, 2013 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Kelli D. Moore is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2013 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my family. v EPIGRAPH The extent to which the solution of theoretical riddles is the task of practice and effected through practice, just as true practice is the condition of a real and positive theory, is shown, for example, in fetishism. --Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 Pictures are the things that have been marked with the stigmata of personhood; they exhibit both physical and virtual bodies; they speak to us sometimes literally, sometimes figuratively --W.J.T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures “Really” Want? In an analogy both terms are on an equal footing; ontologically and semiotically. They belong to the each other at the most profound level of their being --Kaja Silverman, Flesh of My Flesh v TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ....................................................................................................................