Urnanshe, Rey-Arquitecto De La Ciudad De Lagash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marten Stol WOMEN in the ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Marten Stol WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson ISBN 978-1-61451-323-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-61451-263-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0021-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Original edition: Vrouwen van Babylon. Prinsessen, priesteressen, prostituees in de bakermat van de cultuur. Uitgeverij Kok, Utrecht (2012). Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson © 2016 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Cover Image: Marten Stol Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing and binding: cpi books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map 5 1 Her outward appearance 7 1.1 Phases of life 7 1.2 The girl 10 1.3 The virgin 13 1.4 Women’s clothing 17 1.5 Cosmetics and beauty 47 1.6 The language of women 56 1.7 Women’s names 58 2 Marriage 60 2.1 Preparations 62 2.2 Age for marrying 66 2.3 Regulations 67 2.4 The betrothal 72 2.5 The wedding 93 2.6 -

The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict 9

CHAPTER I Introduction: Early Civilization and Political Organization in Babylonia' The earliest large urban agglomoration in Mesopotamia was the city known as Uruk in later texts. There, around 3000 B.C., certain distinctive features of historic Mesopotamian civilization emerged: the cylinder seal, a system of writing that soon became cuneiform, a repertoire of religious symbolism, and various artistic and architectural motifs and conven- tions.' Another feature of Mesopotamian civilization in the early historic periods, the con- stellation of more or less independent city-states resistant to the establishment of a strong central political force, was probably characteristic of this proto-historic period as well. Uruk, by virtue of its size, must have played a dominant role in southern Babylonia, and the city of Kish probably played a similar role in the north. From the period that archaeologists call Early Dynastic I1 (ED 11), beginning about 2700 B.c.,~the appearance of walls around Babylonian cities suggests that inter-city warfare had become institutionalized. The earliest royal inscriptions, which date to this period, belong to kings of Kish, a northern Babylonian city, but were found in the Diyala region, at Nippur, at Adab and at Girsu. Those at Adab and Girsu are from the later part of ED I1 and are in the name of Mesalim, king of Kish, accompanied by the names of the respective local ruler^.^ The king of Kish thus exercised hegemony far beyond the walls of his own city, and the memory of this particular king survived in native historical traditions for centuries: the Lagash-Umma border was represented in the inscriptions from Lagash as having been determined by the god Enlil, but actually drawn by Mesalim, king of Kish (IV.1). -

Entemena Was the Fifth Ruler of the So-Called Urnanse Dynasty in The

ON THE MEANING OF THE OFFERINGS FOR THE STATUE OF ENTEMENA TOSHIKO KOBAYASHI I. Introduction Entemena was the fifth ruler of the so-called Urnanse dynasty in the Pre- Sargonic Lagas and his reign seemed to be prosperous as same as that of Ean- natum, his uncle. After the short reign of Enannatum II, his son, Enentarzi who had been sanga (the highest administrator) of the temple of Ningirsu became ensi. Then, his son Lugalanda suceeded him, but was soon deprived of his political power by Uruinimgina. The economic-administrative archives(1) of Lagas which are the most important historical materials for the history of the Sumerian society were written during a period of about twenty years from Enentarzi to Urui- nimgina, and a greater part of those belong to the organization called e-mi (the house of the wife (of the ruler)). Among those, there exist many texts called nig-gis-tag-ga texts,(2) which record offerings to deities, temples and so on mainly on festivals. In those we can find that statues of Entemena and others receive offerings. I will attempt to discuss the meaning of offerings to these statues, especially that of Entemena in this article. II. The statues in nig-gis-tag-ga texts 1. nig-gis-tag-ga texts These are detailed account books of the kind and the quantity of offerings which a ruler or his wife gave to deities, temples and so on. We find a brief and compact summarization of the content at the end of the text, such as follows: DP 53, XIX, 1) ezem-munu4-ku- 2) dnanse-ka 3) bar-nam-tar-ra 4) dam-lugal- an-da 5) ensi- 6) lagaski-ka-ke4 7) gis be-tag(3) III "At the festival of eating malt of Nanse, Barnamtarra, wife of Lugalanda, ensi of Lagas, made the sacrifice (of them)." Though the agent who made the sacrifice in the texts is almost always a wife of a ruler, there remain four texts, BIN 8, 371; Nik. -

" King of Kish" in Pre-Sarogonic Sumer

"KING OF KISH" IN PRE-SAROGONIC SUMER* TOHRU MAEDA Waseda University 1 The title "king of Kish (lugal-kiski)," which was held by Sumerian rulers, seems to be regarded as holding hegemony over Sumer and Akkad. W. W. Hallo said, "There is, moreover, some evidence that at the very beginning of dynastic times, lower Mesopotamia did enjoy a measure of unity under the hegemony of Kish," and "long after Kish had ceased to be the seat of kingship, the title was employed to express hegemony over Sumer and Akked and ulti- mately came to signify or symbolize imperial, even universal, dominion."(1) I. J. Gelb held similar views.(2) The problem in question is divided into two points: 1) the hegemony of the city of Kish in early times, 2) the title "king of Kish" held by Sumerian rulers in later times. Even earlier, T. Jacobsen had largely expressed the same opinion, although his opinion differed in some detail from Hallo's.(3) Hallo described Kish's hegemony as the authority which maintained harmony between the cities of Sumer and Akkad in the First Early Dynastic period ("the Golden Age"). On the other hand, Jacobsen advocated that it was the kingship of Kish that brought about the breakdown of the older "primitive democracy" in the First Early Dynastic period and lead to the new pattern of rule, "primitive monarchy." Hallo seems to suggest that the Early Dynastic I period was not the period of a primitive community in which the "primitive democracy" was realized, but was the period of class society in which kingship or political power had already been formed. -

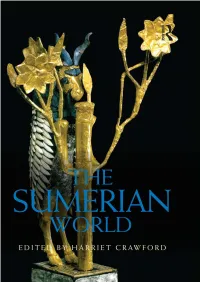

Routledge Worlds : Sumerian World

THE SUMERIANᇹᇺᇻ WORLD The Sumerian World explores the archaeology, history and art of southern Mesopotamia and its relationships with its neighbours from c.3000 to 2000BC. Including material hitherto unpublished from recent excavations, the articles are organised thematically using evidence from archaeology, texts and the natural sciences. This broad treatment will also make the volume of interest to students looking for comparative data in allied subjects such as ancient literature and early religions. Providing an authoritative, comprehensive and up-to-date overview of the Sumerian period written by some of the best-qualified scholars in the field, The Sumerian World will satisfy students, researchers, academics and the knowledgeable layperson wishing to understand the world of southern Mesopotamia in the third millennium. Harriet Crawford is Reader Emerita at UCL’s Institute of Archaeology and a senior fellow at the McDonald Institute, Cambridge. She is a specialist in the archaeology of the Sumerians and has worked widely in Iraq and the Gulf. She is the author of Sumer and the Sumerians (second edition, 2004). THE ROUTLEDGE WORLDS THE REFORMATION WORLD THE ROMAN WORLD Edited by Andrew Pettegree Edited by John Wacher THE MEDIEVAL WORLD THE HINDU WORLD Edited by Peter Linehan, Janet L. Nelson Edited by Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby THE BYZANTINE WORLD THE WORLD OF THE Edited by Paul Stephenson AMERICAN WEST Edited by Gordon Morris Bakken THE VIKING WORLD Edited by Stefan Brink in collaboration THE ELIZABETHAN WORLD with Neil Price Edited by Susan Doran and Norman Jones THE BABYLONIAN WORLD THE OTTOMAN WORLD Edited by Gwendolyn Leick Edited by Christine Woodhead THE EGYPTIAN WORLD THE VICTORIAN WORLD Edited by Toby Wilkinson Edited by Marin Hewitt THE ISLAMIC WORLD THE ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN Edited by Andrew Rippin WORLD Edited by Augustine Casiday THE WORLD OF POMPEI Edited by Pedar W. -

Royal Ideology in Mesopotamian Iconography of the Third and Second Millennia BCE with Special Reference to Gestures

Royal Ideology in Mesopotamian Iconography of the Third and Second Millennia BCE with Special Reference to Gestures by Jonathan Michael Westhead Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Izak Cornelius March 2015 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2015 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT This thesis aims to examine to what extent the visual representations of ancient Mesopotamia portrayed the royal ideology that was present during the time of their intended display. The iconographic method is used in this study and this allows for a better understanding of the meaning behind the work of art. This method allows the study to better attempt to comprehend the underlying ideology of the work of art. The eight images studied date between three thousand BCE and one thousand BCE and this provides a broad base for the study. By having such a broad base it enables the study to provide a brief understanding of how the ideology adapted over two thousand years. The broad base also enables the study to examine a variety of different gestures that are portrayed on the representations. -

The Mesopotamian Origins of the Hittite Double-Headed Eagle

chariton UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research XIV (2011) The Mesopotamian Origins of the Hittite Double-Headed Eagle Jesse D. Chariton Faculty Sponsor: Mark W. Chavalas, Department of History ABSTRACT The figure of a double-headed bird is represented in many cultures around the globe, and in various time periods. “The double-headed eagle has been a royal symbol throughout its history until the present day” (Deeds 1935:106). The history of the use of the double-headed eagle in various contexts since the Crusades has been well documented. It has been used as a heraldic emblem of many royal houses, and is still a state symbol in some countries. However, ancient Near Eastern cultures had used the double-headed bird motif millennia before the Crusades. One striking example is that of the Hittites, for whom it was a “royal insignia” (Collins 2010:60). This paper explores the Mesopotamian origins of the double-headed eagle motif as used by the Hittites. Keywords: double-headed eagle, Hittite, comparative iconography INTRODUCTION There has been little research on the use of the double-headed eagle motif before the Common Era. Some research has been done on double-headed animal imagery (Mundkur 1984), but generally it is part of a broader study (e.g. Mollier 2004). Rudolf Wittkower, in his study of the eagle and snake motif, gives passing mention of the double-headed eagle in a footnote, indicating that it was out of the scope of his article and directing the reader to “relevant material” in other articles (Wittkower 1939:Note 10). That the double-headed eagle motif appears on Hittite monuments in central Anatolia has been cited since their discovery by Charles Texier in the early 19th century. -

Concept of Leadership in the Ancient History and Its Effects on the Middle Easti

Sociology and Anthropology 4(8): 710-718, 2016 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/sa.2016.040805 Concept of Leadership in the Ancient History and Its i Effects on the Middle East Ercüment Yildirim Department of History, Kahramanmaras Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Sutcu Imam University, Turkey Copyright©2016 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract This paper is not written for political reasons. countries around them [1]. The expression of the Middle East This study presents the perceptions about how the was used in 1902 for the first time by Alfred Thayer Mahan communities lived in the Middle East, which has been the (1840-1914), a naval officer and academician [2]. In this center for religious, economic and political conflicts description, which were admitted in a short time, the throughout history and how it has been ruled since the geographical borders were not drawn and the description of ancient times and how they can be ruled today. The aim of the Middle East was shaped in accordance with the political the study is to reveal the origins of the lifestyle of Middle borders of the countries. When we think about the Middle Eastern people whom have only been gathered together East in present, the borders which extend to Iran in the East, under the hegemony of a leader. The Sumerian community, Egypt in the West, Turkey in the North and Yemen in the who has organized city kingdoms, formed the first legal state South, comes up in our minds. -

OXFORD EDITIONS of CUNEIFORM TEXTS the Weld-Blundell

OXFORD EDITIONS OF CUNEIFORM TEXTS Edited under the Direction of S. LANGDON, Professor of Assyriology. VOLUME II The Weld-Blundell Collection, vol. II. Historical Inscriptions, Containing Principally the Chronological Prism, W-B. 444, by S. LANGDON, M. A. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen New York Toronto Melbourne Cape Town Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai Humphrey Milford 1923 PREFACE. The fortunate discovery of the entire chronological tables of early Sumerian and Bbylonian history provides ample reason for a separate volume of the Weld-Blundell Series, and thle imme- diate publication of this instructive inscription is imperative. It constitutes the most important historical document of its kind ever recovered among cuneiform records. The Collection of the Ashmolean Museum contains other historical records which I expected to include in this volume, notably the building inscriptions of Kish, excavated during the first year's work of the Oxford and Field Museum Expedition. MR. WELD-BLUNDELL who supports this expedition on behalf of The University of Oxford rightly expressed the desire to have his dynastic prism prepared for publication before the writer leaves Oxford to take charge of the excavations at Oheimorrl (Kish) the coming winter. This circumstance necessitates the omission of a considerable nulmber of historical texts, which must be left over for a future volume. I wish also that many of the far reaching problems raised by the new dynastic prism might have received more mature discussion. The most vital problem, concerning which I am at present unable to decide, namely the date of the first Babylonian dynasty, demands at least special notice some-where in this book. -

The Indian King Lists John Davis Pilkey May 14, 2008

The Indian King Lists John Davis Pilkey May 14, 2008 East Indian tradition is vitally important to Kingship at Its Source in the Mahadevi tetrad and the Inanna Succession as determined by the union of Kasyapa and Diti. However this tradition, like others, possesses its own peculiar limitations. Even more than Hellenic mythology, the Indian is so rich in names that much of it pertains to times too late to fall within the early postdiluvian period. Owing to the lengthy genealogy ending in Krishna, I have never considered an early postdiluvian identity for that important Hindu god. The remarkably extended Indian king lists given by Waddell are used only sparingly in Kingship at Its Source for a few selected names to which Waddell gives cross-cultural Sumero-Akkadian identities— Haryashwa for Ur Nanshe and Sagara and Asa Manja for Sargon and Manishtushu. Because these names occur randomly at the 15 th , 37 th and 38 th generations of the solar line of Ayodhya, I have not yet attempted a comprehensive explanation of the Indian list or determined why these few names should pop out of context to agree with Sumerian records. The values I give these names are entirely dependent on L. A. Waddell’s work in Makers of Civilization (1928). The present essay is something of a juggling act because it deals with so many different lists as basis for comparison and identification. The reader should keep in mind that I am referring to the following sources: (1) four simultaneous lines of the Indian king lists which Waddell has abstracted from texts known as Puranas— the Ayodhya and Videha solar lines and Yadu and Puru lunar lives, (2) Sumerian king lists such as the “Kish Chronicle” as transliterated and arranged by Waddell, (3) the comprehensive Sumerian King List, including many of the same names, as translated by Samuel Noah Kramer, (4) the charts of simultaneous Sumerian dynasties based on inscriptional evidence as presented by William Hallo and (5) the biblical lists of Noahic patriarchs in Genesis 10-11. -

The Sumerians

THE SUMERIANS THE SUMERIANS THEIR HISTORY, CULTURE, AND CHARACTER Samuel Noah Kramer THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago & London THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1963 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved Published 1963 Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0-226-45237-9 (clothbound); 0-226-45238-7 (paperbound) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 63-11398 89 1011 12 To the UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA and its UNIVERSITY MUSEUM PREFACE The year 1956 saw the publication of my book From the Tablets of Sumer, since revised, reprinted, and translated into numerous languages under the title History Begins at Sumer. It consisted of twenty-odd disparate essays united by a common theme—"firsts" in man s recorded history and culture. The book did not treat the political history of the Sumerian people or the nature of their social and economic institutions, nor did it give the reader any idea of the manner and method by which the Sumerians and their language were discovered and "resurrected/' It is primarily to fill these gaps that the present book was conceived and composed. The first chapter is introductory in character; it sketches briefly the archeological and scholarly efforts which led to the decipher ment of the cuneiform script, with special reference to the Sumerians and their language, and does so in a way which, it is hoped, the interested layman can follow with understanding and insight. The second chapter deals with the history of Sumer from the prehistoric days of the fifth millennium to the early second millennium B.C., when the Sumerians ceased to exist as a political entity. -

In This Paper, I Will Examine Whether the Peg Figurine(1)

A STUDY OF THE PEG FIGURINE WITH THE INSCRIPTION OF ENANNATUM I* TOSHIKO KOBAYASHI** Introduction In this paper, I will examine whether the peg figurine(1) engraved with the inscription of Enannatum I, the fourth ruler of the Urnanshe dynasty, during the Early Dynasic Period in Lagash, represents his personal deity Shulutul. In ancient Mesopotamia, it was customary for builders to bury inscribed founda- tion deposits(2)-peg figurines, stone tablets and so on-in the foundation of buildings such as temples. At present, there are at least ten peg figurines that contain the inscription of Enannatum I on the lower half of their bodies and have a stick form(3) (Fig. 1). All are made of copper and assume the same pose, having long hair flowing down their back and clasping their hands in front of their chest. The most significant characteristic is that the heads bear a single pair of protuberances. R. D. Biggs,(4) V. E. Crawford(5) et al.(6) regard these peg figurines as Shulutul, the personal deity of Enannatum I, for they regard a pair of protuberances as horns indicating a deity and point out that those dug out of the Ibgal temple of Inanna were identified with Shulutul by their inscription. The analysis of the inscriptions by these scholars is not complete, so I will try to analyze royal inscriptions and examine whether the peg figurines represent Shulutul. I. The Construction of the Inscription The inscription is given below. Since the inscription of the peg figurine in Corpus, EN. I, 22 is badly damaged and the inscription on boulder B in ibid., EN.